Sale 2432 - Lot 117

Price Realized: $ 5,000

Price Realized: $ 6,250

?Final Price Realized includes Buyer’s Premium added to Hammer Price

Estimate: $ 8,000 - $ 12,000

"SCATTERED, KNEW NOT WHERE TO GO" (CIVIL WAR--CONNECTICUT.) Taylor, Charles L. Correspondence and diary of a lucky sergeant in the 16th Connecticut. 449 items (2.5 linear feet), including: 130 letters from Charles L. Taylor to his wife Harriet, 1862-65, each with original stamped and postmarked envelope * 93 letters from Taylor to his parents and family, 1862-65, many with original envelopes * 219 letters from Harriet to Charles, 1862-65, most with original envelopes * Charles's 10-page diary-memoir circa 1865 * 6 letters from other Civil War soldiers to Charles and family, 1864-65; condition generally strong. Vp, bulk 1862-65

Additional Details

Charles Lyman Taylor (1837-1909) of Bristol, CT married his sweetheart Harriet Tuttle (1840-1899) just days before his enlistment with the 16th Connecticut Infantry as a sergeant in August 1862. A month later, the unprepared regiment took very heavy losses at Antietam, followed by further fighting at Fredericksburg and elsewhere. Almost all of the survivors were captured at North Carolina in 1864, and sent to the dreaded Andersonville Prison. A recent history is titled "A Broken Regiment: The 16th Connecticut's Civil War." Taylor was one of the luckiest members of this luckless group.

This unusually large and complete archive of his war-date correspondence includes four distinct records of his entire three years of service: his letters to both his wife and his "dear friends at home", his diary / memoir, and his wife's letters to him. The key events of his service are thus reflected in several different ways. He wrote to his wife two days after the Antietam disaster on 19 September 1862, where a quarter of the regiment was killed or wounded before their disorderly retreat: "We miss Capt. Manross sadly. His last words were 'My wife.' . . . We suffered more severely on account of our large guns getting out of the proper ammunition. I expect that we were most of us exposed to as hot fire for a time as is often experienced. . . . I could see the bullets strike around me. . . . I stayed as long as I could see our company, and when they were all leaving I left. . . . I fired one shot before leaving the corn field and but one, as we had no order, and the rebels came into the cornfield with our colors, thus deceiving our officers." To his parents on 28 September, he wrote "We were exposed to shells and shots very much of the day, and to musketry in a cornfield the latter part of the day. The latter was very destructive, about as warm as it is experienced I expect." In his diary, which was apparently written out in 1865 on New Bern headquarters letterhead, he wrote on Antietam that "In the cornfield the rebs confronted us with Union colors &c, were ordered not to fire on our men, but got unmercifully fired on. . . . Were scattered, knew not where to go. Helped one wounded man, a stranger, to the hospital." Finally, we have his wife's relief at his survival: "I do indeed thank God that he has spared you, that from out of that terrible battle you came unscathed. . . . Four weeks tonight since I gave you my hand, promising before God and man to be yours always. We little thought then how soon you could be called into battle into the midst of danger."

On 15 December, he described to his wife more fighting at Fredericksburg: "One of our artillery pieces did not throw its shots well, causing execution in our own ranks. . . . We were marched about dark directly toward where it was going on, and we could hear the constant cracking of the rifles and see the flashing of the firing from them so distinctly. Our forces charging on a battery, they did not take it." He discussed the Siege of Suffolk on 4 May 1863: "On a skirmish against the Rebels . . . A field we had to cross was particularly exposed to the field of fire of two of the rebel cannon they had brought to bear in good range, firing case shell. This was about the hottest fire we were under, yet but one was wounded."

Next came Taylor's biggest stroke of good luck. In August 1863, he was detached to serve as a clerk in the division headquarters under General George W. Getty, stationed near Falmouth, VA. With his somewhat stable posting, Hattie contemplated coming to work in a nearby camp for freed slaves, to which he responded "About your coming to Fort Monroe to teach contrabands, I don't know. . . . I think you would find it not near as pleasant as teaching neat intelligent white children" (30 January 1864). She soon responded "I do not suppose it would be very pleasant, but it would be doing good, and I don't think I am doing much good here. . . . Thus end my thoughts of being a contraband teacher."

Meanwhile, Charles's 16th Connecticut comrades were assigned to a garrison at Plymouth, NC. On 16 April 1864, he was ordered to rejoin his regiment in Plymouth. Four days later, he was on an army transport steamer, watching the garrison being besieged and then captured by a superior Confederate force: "It is a sad thing, our regiment being taken, for us & them, and I escaped it but by a day." By the next day when he finished the letter, most of the regiment was on its way to Andersonville Prison, but Taylor was stationed on Roanoke Island with Company H, the one company of the 16th that had escaped. He spent the rest of the war as a clerk in the 18th Army Corps headquarters in New Bern, NC. He witnessed a grisly botched military execution on 14 August 1864 (described in a letter to the parents), but was most affected by the death of Lincoln. He struggled to convey optimism about Andrew Johnson to his parents on 23 April: "President Johnson I think probably will be equal to what is expected of him, notwithstanding that he was 'tight' when being inaugurated as vice president. . . . it is better than to say he is going to be a drunkard and our country is going to ruin."

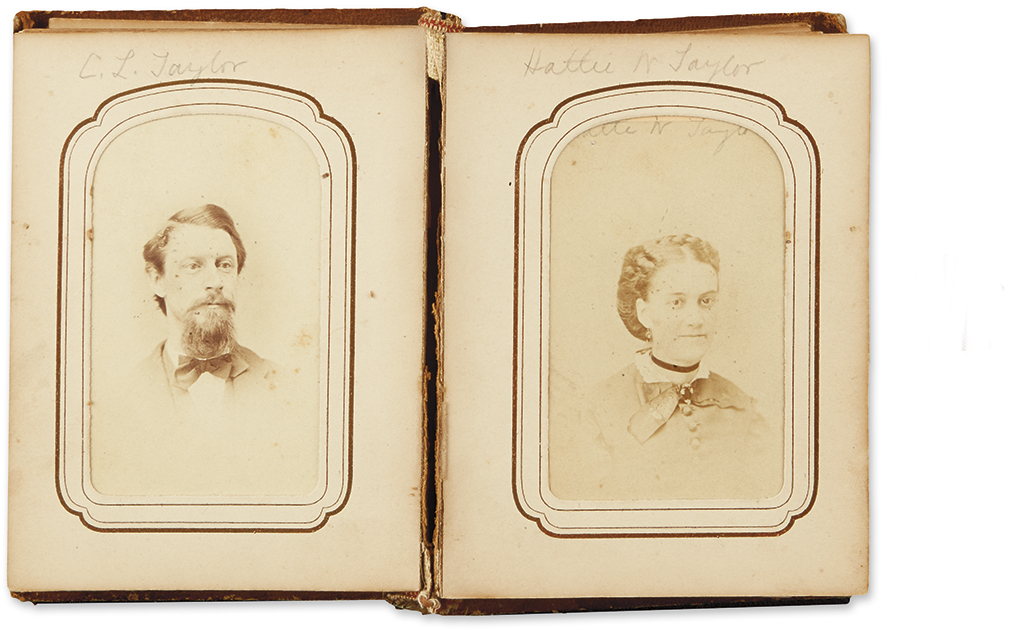

with--related family papers including a wooden box of approximately 255 family letters between Taylor, his parents, siblings, wife, and others (though not Taylor's war-date letters), most in original stamped and postmarked envelopes, circa 1862-80 Album with 31 photographs circa 1860s-70s, most of them cartes de visite, most identified, all apparently family members, 4 depicting Charles L. Taylor and one of his wife Harriet Oil portrait of his daughter circa 1875 10 x 8 oval photographs of his parents Notes on Taylor's career through 1891 1859 family Bible with 10 pages of notes and family register entries, 1862-95.

This unusually large and complete archive of his war-date correspondence includes four distinct records of his entire three years of service: his letters to both his wife and his "dear friends at home", his diary / memoir, and his wife's letters to him. The key events of his service are thus reflected in several different ways. He wrote to his wife two days after the Antietam disaster on 19 September 1862, where a quarter of the regiment was killed or wounded before their disorderly retreat: "We miss Capt. Manross sadly. His last words were 'My wife.' . . . We suffered more severely on account of our large guns getting out of the proper ammunition. I expect that we were most of us exposed to as hot fire for a time as is often experienced. . . . I could see the bullets strike around me. . . . I stayed as long as I could see our company, and when they were all leaving I left. . . . I fired one shot before leaving the corn field and but one, as we had no order, and the rebels came into the cornfield with our colors, thus deceiving our officers." To his parents on 28 September, he wrote "We were exposed to shells and shots very much of the day, and to musketry in a cornfield the latter part of the day. The latter was very destructive, about as warm as it is experienced I expect." In his diary, which was apparently written out in 1865 on New Bern headquarters letterhead, he wrote on Antietam that "In the cornfield the rebs confronted us with Union colors &c, were ordered not to fire on our men, but got unmercifully fired on. . . . Were scattered, knew not where to go. Helped one wounded man, a stranger, to the hospital." Finally, we have his wife's relief at his survival: "I do indeed thank God that he has spared you, that from out of that terrible battle you came unscathed. . . . Four weeks tonight since I gave you my hand, promising before God and man to be yours always. We little thought then how soon you could be called into battle into the midst of danger."

On 15 December, he described to his wife more fighting at Fredericksburg: "One of our artillery pieces did not throw its shots well, causing execution in our own ranks. . . . We were marched about dark directly toward where it was going on, and we could hear the constant cracking of the rifles and see the flashing of the firing from them so distinctly. Our forces charging on a battery, they did not take it." He discussed the Siege of Suffolk on 4 May 1863: "On a skirmish against the Rebels . . . A field we had to cross was particularly exposed to the field of fire of two of the rebel cannon they had brought to bear in good range, firing case shell. This was about the hottest fire we were under, yet but one was wounded."

Next came Taylor's biggest stroke of good luck. In August 1863, he was detached to serve as a clerk in the division headquarters under General George W. Getty, stationed near Falmouth, VA. With his somewhat stable posting, Hattie contemplated coming to work in a nearby camp for freed slaves, to which he responded "About your coming to Fort Monroe to teach contrabands, I don't know. . . . I think you would find it not near as pleasant as teaching neat intelligent white children" (30 January 1864). She soon responded "I do not suppose it would be very pleasant, but it would be doing good, and I don't think I am doing much good here. . . . Thus end my thoughts of being a contraband teacher."

Meanwhile, Charles's 16th Connecticut comrades were assigned to a garrison at Plymouth, NC. On 16 April 1864, he was ordered to rejoin his regiment in Plymouth. Four days later, he was on an army transport steamer, watching the garrison being besieged and then captured by a superior Confederate force: "It is a sad thing, our regiment being taken, for us & them, and I escaped it but by a day." By the next day when he finished the letter, most of the regiment was on its way to Andersonville Prison, but Taylor was stationed on Roanoke Island with Company H, the one company of the 16th that had escaped. He spent the rest of the war as a clerk in the 18th Army Corps headquarters in New Bern, NC. He witnessed a grisly botched military execution on 14 August 1864 (described in a letter to the parents), but was most affected by the death of Lincoln. He struggled to convey optimism about Andrew Johnson to his parents on 23 April: "President Johnson I think probably will be equal to what is expected of him, notwithstanding that he was 'tight' when being inaugurated as vice president. . . . it is better than to say he is going to be a drunkard and our country is going to ruin."

with--related family papers including a wooden box of approximately 255 family letters between Taylor, his parents, siblings, wife, and others (though not Taylor's war-date letters), most in original stamped and postmarked envelopes, circa 1862-80 Album with 31 photographs circa 1860s-70s, most of them cartes de visite, most identified, all apparently family members, 4 depicting Charles L. Taylor and one of his wife Harriet Oil portrait of his daughter circa 1875 10 x 8 oval photographs of his parents Notes on Taylor's career through 1891 1859 family Bible with 10 pages of notes and family register entries, 1862-95.

Exhibition Hours

Exhibition Hours

Aliquam vulputate ornare congue. Vestibulum maximus, libero in placerat faucibus, risus nisl molestie massa, ut maximus metus lectus vel lorem.