Sale 2580 - Lot 25

Price Realized: $ 20,000

Price Realized: $ 25,000

?Final Price Realized includes Buyer’s Premium added to Hammer Price

Estimate: $ 4,000 - $ 6,000

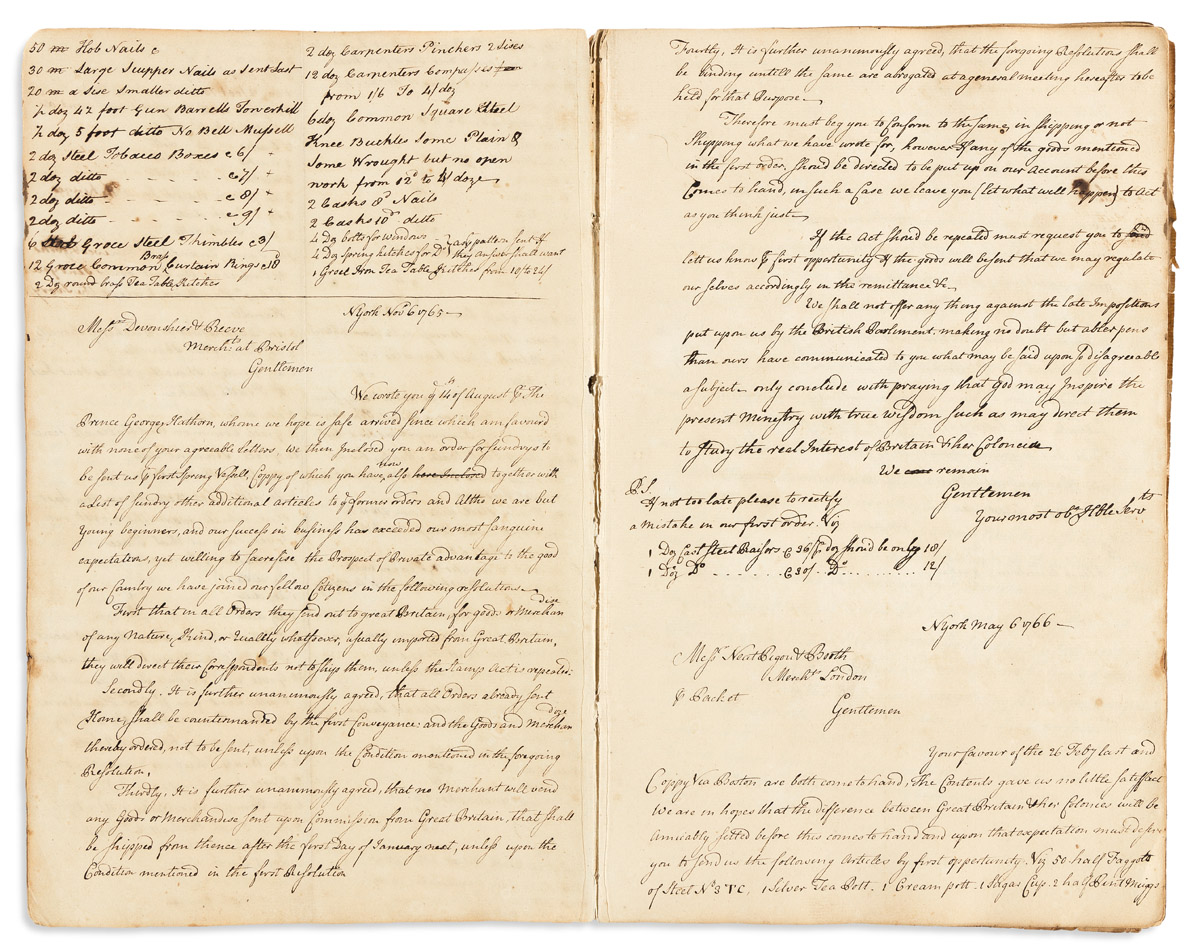

"AMERICA MUST IN A SHORT TIME BE THE HABITATION OF BANKRUPTS, BEGGARS & SLAVES" (AMERICAN REVOLUTION--PRELUDE.) Opposition to the Stamp Act as seen in the letterbook of a New York iron merchant. [82] manuscript pages, including retained copies of 77 letters and 8 detailed merchandise orders. Folio, 13 x 8 inches, disbound; many pages loose and possibly a small number absent, moderate edge wear with minimal loss of text. New York, February 1765 to April 1771

Additional Details

Garret Abeel (1734-1799) and his brother-in-law Evart Byvanck (1744-1805) began a successful partnership as Manhattan iron merchants in 1765. This letterbook contains retained drafts for much of their correspondence through 1771, reflecting a tumultuous period which led to the American Revolution. Most of the letters are to the firm's British suppliers of finished metal goods, and many discuss the dominant issue of the day: organized American resistance to British taxation. Abeel and Byvanck often made their orders contingent upon repeal of the Stamp Act or some other Parliamentary action, and pressured their wealthy suppliers to use their clout to restore trade. They often cited the joint resolutions of American merchants, including a flurry of letters written in the week after the Non-Importation Act of 1765.

The letterbook begins with a letter of introduction to the British firm of Devonshire & Reeve, followed by a 3-page itemized list of iron goods the young Americans ordered from them on 6 February 1765, as well as a similarly large follow-up order placed in August. Abeel & Byvanck was off to a grand start with a major British supplier; imagine their consternation with the imposition of the Stamp Act and the resulting Non-Importation Agreement entered by the leading New York merchants on 31 October 1765. That same day they sent a letter to British merchants Neate, Pigou & Booth: "If it had not been for the late acts of Parliament such as the Sugar and Stamp Acts, should have wanted several large articles sent us by your house, but while they are in being, dare not order a single article in the way of trade, nor do we believe anyone else from this place will order goods till those acts are repealed." Abeel & Byvanck drafted a stern letter to their main supplier Devonshire & Reeve on 2 November 1765, asking to send their last order "only in case the Stamp Act is repealed . . . for should not the late strictures laid upon our trade by the Parliament be taken off, America must in a short time be the habitation of bankrupts, beggars & slaves. . . . In money we are sure they cannot be paid long. That, like a bird of passage, flies or has already fled from our inhospitable land." The young merchants took four days to calm down, crossed out this version of the letter, and drafted another less confrontational version which summarized the Non-Importation Agreement: "Altho we are but young beginners, and our success in business has exceeded our most sanguine expectations, yet willing to sacrifice the prospect of private advantage to the good of our country we have joined our fellow citizens in the following resolutions: First, that in all orders they send out to Great Britain for goods or merchandise . . . they will direct their correspondents not to ship them, unless the Stamp Act is repealed. . . . We shall not offer anything against the late impositions put upon us by the British Parliament, making no doubt but abler pens than ours have communicated to you what may be said on so disagreeable a subject."

On 27 August 1766, the firm wrote again to Devonshire & Reeve to discuss the recent repeal: "Upon the receipt of the account of the repeal of the Stamp Act, the Americans were softned down more speedy that could be imagined. The words tyranny, oppression & rebellion were no more heard. Evryone strove how he should most express his loyalty to the best of Kings and gratitude to the patriotick ministry." However, "the life of trade is still wanting, circulating mediam is nearly sunk, and we are debard the liberty of making any more paper money."

The 24 September 1766 letter to Devonshire & Reeve reflects a return to normal trade across the Atlantic, but with a new wrinkle: "As there is some likelihood of a war between England and France. If such a thing should happen . . . send us by first opportunity two tons of best FF powder over and above what we have already ordered as also two tons shot sorted, two cask bar lead, & one doz four foot gun barrels. Please to let the powder be unglazed." On 16 January 1767 they wrote to Reeve, thanking "those who were our friends at home in obtaining the repeal of the Stamp Act" who "certainly deserve a greatfull return for their services." Apparently Abeel & Byvanck and other patriotic American merchants were trying to support these allies in trade, but certain shady British merchants were attempting to break into the trade with unrealistic bargains on shoddy goods. A 7 April 1767 letter makes passing reference to the British commander in North America Thomas Gage, who apparently helped settle the firm's debts in New York. On 24 August 1767 they assured Reeve that "N. Yorkers are far from being separated from the mother country, altho it may be the opinion of many in your part of the world that they are ripe for a rebellion. . . . It's true the rigorous proceedings of the H of C makes many people think hard of it, but what can we do but grin & bear it?"

The firm's 19 November 1768 letter to British supplier Henry Cruger finds them again pressuring their British friends to pressure Parliament, offering to place a large order only "if the acts of Parliament imposing duties on paper, paint & glass are repealed, which I hope & flatter ourselves will be done through the influence of our good friends in London, Bristol &c." They wrote similarly to Cruger on 30 September 1769: "We flatter ourselves that through the struggles of our friends in Europe & the methods pursued by us, we shall get relieved from the oppressive acts at the next meeting of Parliament." A remarkable long letter dated 12 October 1769 sets forth the many ways which British tax policy has brought the colonies together: "They have been the means of uniting the colonies in a bond of friendship &c which we hope will last forever. They have made the Americans more frugal & industrious by . . . forcing them to enter upon the manufactory of a great many articles which they before imported from Great Britain."

The American merchants remained firm. Abeel & Byvanck wrote a British merchant on 10 July 1770: "An express being sent by the committee of merchants in this place to acquaint the people of your place that by taking the sense of the inhabitants of this city, a majority was found for importing all articles from Great Britain except those which are dutable."

Evert Byvanck went to London in 1770, and his partner Abeel wrote him a long letter from New York on 16 January 1771: "The uncertainty of war or peace you know gave us uneasyness when you went away. . . . Must again request you not to send too many goods, knowing the critical situation of affairs as to peace or war." Although the letterbook ends in April 1771, Abeel remained an avid patriot, and served as a major in the revolution which soon followed.

The mercantile history, to some readers, will be of even greater interest than the machinations over the Stamp Act. The letter book includes several very long and detailed order lists for the finished metalware being imported from England for retail sale in New York. Tools such as hammers and anvils appear frequently, but also great quantities of furniture hardware: cupboard locks, hinges, Chinese handles and much more. The likely market for these goods would be the cabinetmakers of New York, finishing their masterpieces with the latest ornamental hardware from England. Other unusual goods include fish hooks, jew's harps, mouse traps, pewter candle molds, and razors.

WITH--a small archive of business records of the firm after it was passed on to Garret Abeel's son Garret Byvanck Abeel (1768-1829). The firm remained active in Abeel family hands under various partnerships through at least the 4th generation by 1915. These later records include:

Expense ledger for mercantile ships. 18 pages, stitched; defective with perhaps 10% of the text area torn away on each page. Each page is related to a separate ship's voyage, with payments to chandlers, blacksmiths, sailmakers, grocers, advances to crew, and other expenses preparatory to departure. On 20 May 1795, the account lists £16 paid to "the two Negroes who worked their passages" aboard the Brig Diana. July 1794 to January 1796.

Partial daybook of general store sales, [15] pages, stitched. 7 August to 9 October 1806.

A file of 72 receipts, invoices, shipping documents, and promissory notes, 1795-1829.

A file of 38 letters addressed to the firm, 1810-1827. Many of these letters are orders which go into great specificity about the "old sable Russia iron" traded by the Abeels to merchants in the United States and England; others discuss the trade more broadly.

The letterbook begins with a letter of introduction to the British firm of Devonshire & Reeve, followed by a 3-page itemized list of iron goods the young Americans ordered from them on 6 February 1765, as well as a similarly large follow-up order placed in August. Abeel & Byvanck was off to a grand start with a major British supplier; imagine their consternation with the imposition of the Stamp Act and the resulting Non-Importation Agreement entered by the leading New York merchants on 31 October 1765. That same day they sent a letter to British merchants Neate, Pigou & Booth: "If it had not been for the late acts of Parliament such as the Sugar and Stamp Acts, should have wanted several large articles sent us by your house, but while they are in being, dare not order a single article in the way of trade, nor do we believe anyone else from this place will order goods till those acts are repealed." Abeel & Byvanck drafted a stern letter to their main supplier Devonshire & Reeve on 2 November 1765, asking to send their last order "only in case the Stamp Act is repealed . . . for should not the late strictures laid upon our trade by the Parliament be taken off, America must in a short time be the habitation of bankrupts, beggars & slaves. . . . In money we are sure they cannot be paid long. That, like a bird of passage, flies or has already fled from our inhospitable land." The young merchants took four days to calm down, crossed out this version of the letter, and drafted another less confrontational version which summarized the Non-Importation Agreement: "Altho we are but young beginners, and our success in business has exceeded our most sanguine expectations, yet willing to sacrifice the prospect of private advantage to the good of our country we have joined our fellow citizens in the following resolutions: First, that in all orders they send out to Great Britain for goods or merchandise . . . they will direct their correspondents not to ship them, unless the Stamp Act is repealed. . . . We shall not offer anything against the late impositions put upon us by the British Parliament, making no doubt but abler pens than ours have communicated to you what may be said on so disagreeable a subject."

On 27 August 1766, the firm wrote again to Devonshire & Reeve to discuss the recent repeal: "Upon the receipt of the account of the repeal of the Stamp Act, the Americans were softned down more speedy that could be imagined. The words tyranny, oppression & rebellion were no more heard. Evryone strove how he should most express his loyalty to the best of Kings and gratitude to the patriotick ministry." However, "the life of trade is still wanting, circulating mediam is nearly sunk, and we are debard the liberty of making any more paper money."

The 24 September 1766 letter to Devonshire & Reeve reflects a return to normal trade across the Atlantic, but with a new wrinkle: "As there is some likelihood of a war between England and France. If such a thing should happen . . . send us by first opportunity two tons of best FF powder over and above what we have already ordered as also two tons shot sorted, two cask bar lead, & one doz four foot gun barrels. Please to let the powder be unglazed." On 16 January 1767 they wrote to Reeve, thanking "those who were our friends at home in obtaining the repeal of the Stamp Act" who "certainly deserve a greatfull return for their services." Apparently Abeel & Byvanck and other patriotic American merchants were trying to support these allies in trade, but certain shady British merchants were attempting to break into the trade with unrealistic bargains on shoddy goods. A 7 April 1767 letter makes passing reference to the British commander in North America Thomas Gage, who apparently helped settle the firm's debts in New York. On 24 August 1767 they assured Reeve that "N. Yorkers are far from being separated from the mother country, altho it may be the opinion of many in your part of the world that they are ripe for a rebellion. . . . It's true the rigorous proceedings of the H of C makes many people think hard of it, but what can we do but grin & bear it?"

The firm's 19 November 1768 letter to British supplier Henry Cruger finds them again pressuring their British friends to pressure Parliament, offering to place a large order only "if the acts of Parliament imposing duties on paper, paint & glass are repealed, which I hope & flatter ourselves will be done through the influence of our good friends in London, Bristol &c." They wrote similarly to Cruger on 30 September 1769: "We flatter ourselves that through the struggles of our friends in Europe & the methods pursued by us, we shall get relieved from the oppressive acts at the next meeting of Parliament." A remarkable long letter dated 12 October 1769 sets forth the many ways which British tax policy has brought the colonies together: "They have been the means of uniting the colonies in a bond of friendship &c which we hope will last forever. They have made the Americans more frugal & industrious by . . . forcing them to enter upon the manufactory of a great many articles which they before imported from Great Britain."

The American merchants remained firm. Abeel & Byvanck wrote a British merchant on 10 July 1770: "An express being sent by the committee of merchants in this place to acquaint the people of your place that by taking the sense of the inhabitants of this city, a majority was found for importing all articles from Great Britain except those which are dutable."

Evert Byvanck went to London in 1770, and his partner Abeel wrote him a long letter from New York on 16 January 1771: "The uncertainty of war or peace you know gave us uneasyness when you went away. . . . Must again request you not to send too many goods, knowing the critical situation of affairs as to peace or war." Although the letterbook ends in April 1771, Abeel remained an avid patriot, and served as a major in the revolution which soon followed.

The mercantile history, to some readers, will be of even greater interest than the machinations over the Stamp Act. The letter book includes several very long and detailed order lists for the finished metalware being imported from England for retail sale in New York. Tools such as hammers and anvils appear frequently, but also great quantities of furniture hardware: cupboard locks, hinges, Chinese handles and much more. The likely market for these goods would be the cabinetmakers of New York, finishing their masterpieces with the latest ornamental hardware from England. Other unusual goods include fish hooks, jew's harps, mouse traps, pewter candle molds, and razors.

WITH--a small archive of business records of the firm after it was passed on to Garret Abeel's son Garret Byvanck Abeel (1768-1829). The firm remained active in Abeel family hands under various partnerships through at least the 4th generation by 1915. These later records include:

Expense ledger for mercantile ships. 18 pages, stitched; defective with perhaps 10% of the text area torn away on each page. Each page is related to a separate ship's voyage, with payments to chandlers, blacksmiths, sailmakers, grocers, advances to crew, and other expenses preparatory to departure. On 20 May 1795, the account lists £16 paid to "the two Negroes who worked their passages" aboard the Brig Diana. July 1794 to January 1796.

Partial daybook of general store sales, [15] pages, stitched. 7 August to 9 October 1806.

A file of 72 receipts, invoices, shipping documents, and promissory notes, 1795-1829.

A file of 38 letters addressed to the firm, 1810-1827. Many of these letters are orders which go into great specificity about the "old sable Russia iron" traded by the Abeels to merchants in the United States and England; others discuss the trade more broadly.

Exhibition Hours

Exhibition Hours

Aliquam vulputate ornare congue. Vestibulum maximus, libero in placerat faucibus, risus nisl molestie massa, ut maximus metus lectus vel lorem.