Sale 2633 - Lot 25

Price Realized: $ 3,200

Price Realized: $ 4,000

?Final Price Realized includes Buyer’s Premium added to Hammer Price

Estimate: $ 4,000 - $ 6,000

(ARCTIC.) Roy Fitzsimmons. Diary kept on the MacGregor Arctic Expedition to Greenland, discussing the sons of Peary and Henson. [46] manuscript diary pages (75 numbered pages including 29 blanks), plus 3 pages of memoranda. 8vo, original cloth-backed boards, minor wear and dampstaining; minor wear and foxing to contents. Etah, Greenland and elsewhere, 20 March to 31 July [1938]

Additional Details

The MacGregor Arctic Expedition was a privately-funded American scientific expedition which intended to reach Fort Conger in far northern Canada, the base camp of the ill-fated Greely Expedition of 1881-1884. Ten men aboard the ship Gen. A.W. Greely found Fort Conger iced in, so they wintered across the strait in Foulk Fjord, Greenland to undertake their measurements and explorations. Their camp was not far from the village of Etah, then one of the northernmost human settlements in the world.

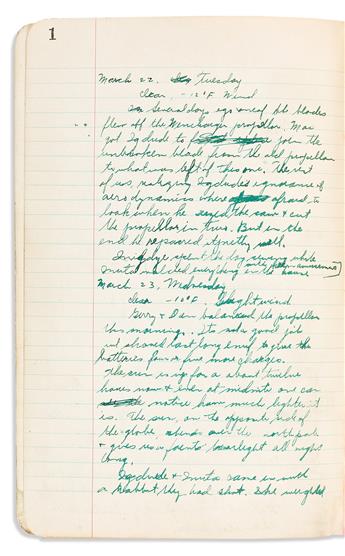

This diary was kept by LeRoy Gerald "Roy" Fitzsimmons (1915-1945), a recent Seton Hall College graduate from Newark, NJ, who served as the expedition's geophysicist and magnetologist. As with the other members of this small expedition, his actual duties were varied, ranging from cook to boat pilot as needed for basic survival. The diary begins several months into the expedition on 20 March 1938, with the approach of springtime after a long dark winter.

The expedition had its share of adventure and peril. While Fitzsimmons did not record his longer forays from the base camp, he did discuss his plans: "Fuzz & I have been planning a sledge trip to Cape Sabine. It depends upon supplies, especially dog pemmican. The trip has its dangers, inasmuch as the ice on Smith Sound is always on the move & very treacherous. Mac Millar in 1924 crossed in seven hours, while Kane 50 years ago required 31 days to make the trip" (4 April). He recorded a short expedition to gather cached gear on 15 May: "The seventeen dogs were at a full gallop a good part of the time, and going on the ice foot we were in constant danger of turning the sledge over or breaking a leg on the abutting rocks or countless pieces of rough ice." Because of the tide, "on the way up we had little trouble in getting on and off the ledge, but on the way back the sea ice was at least six feet below the ledge, and in order to get off we merely drove off on the fly."

The expedition's plane was piloted by Isaac "Ike" Schlossbach, whose life was often at risk. On 13 April, on take-off "the engine sputtered and for a few seconds it looked like curtains. But the engine caught and he continued his climb." The undercarriage was then crushed during the landing. Ike later took the plane for a survey of Inglefield Land further up the Greenland coast, but nearly ran out of fuel on the flight back to Etah: "As he taxied into the ship, the motor stopped several times from lack of gas. It was a close call, limping back the way he did. Ike seems to bear a charmed life" (22 May).

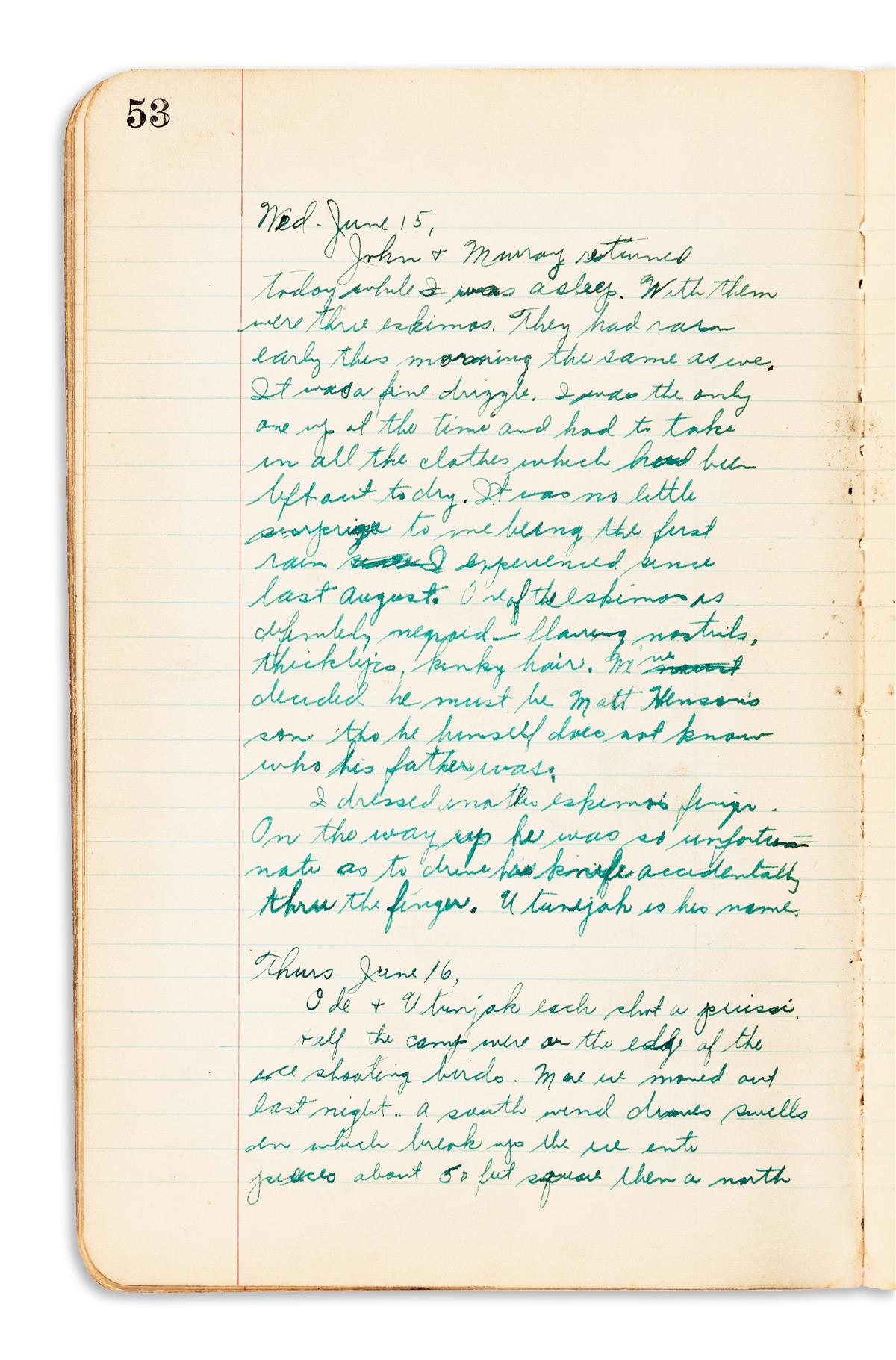

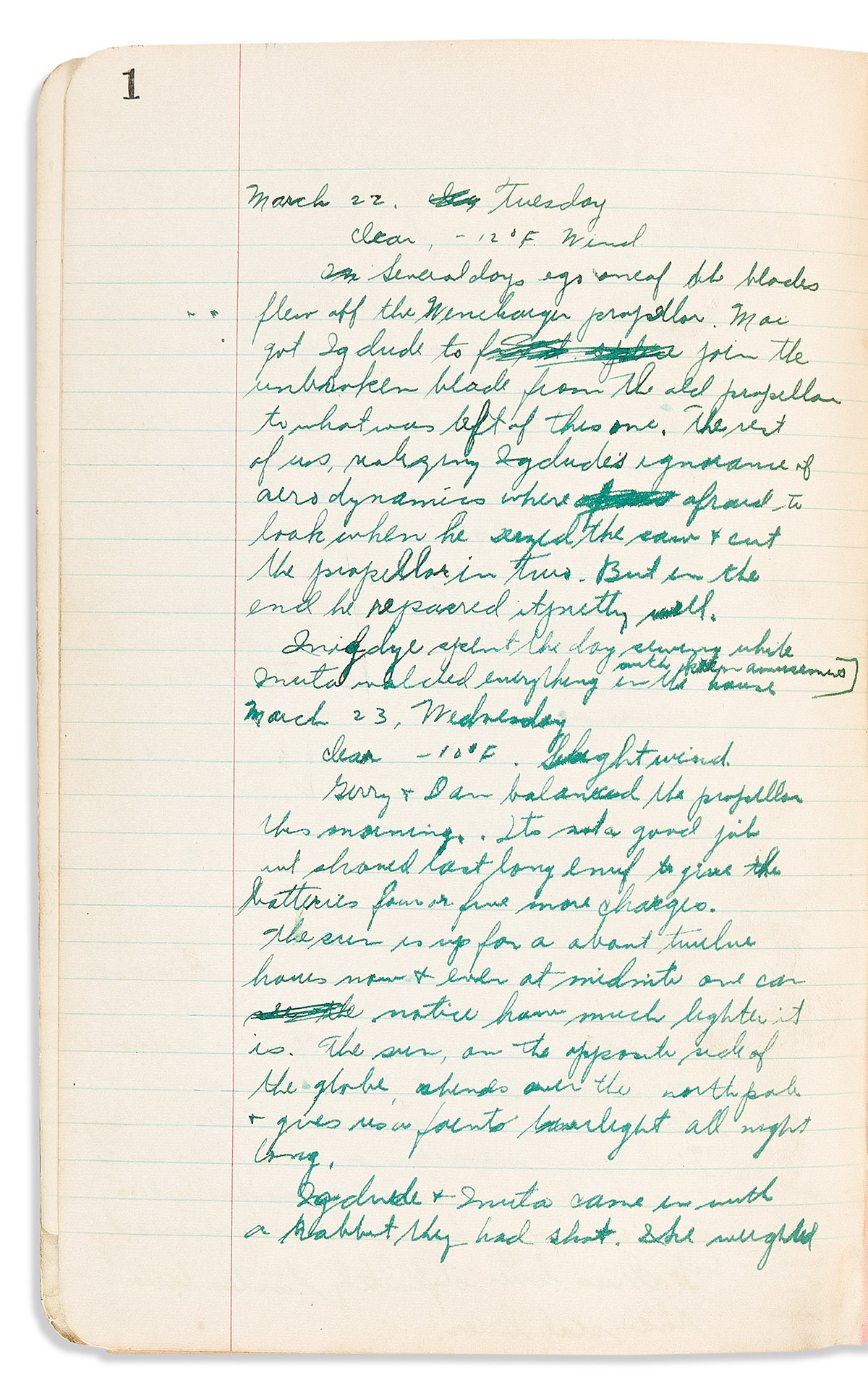

The expedition had frequent interactions with the local Inuit, who were either hired as laborers in camp, or would visit the camp for curiosity and sociability. Fitzsimmons was very friendly with the Inuit, making every effort to communicate and record his impressions, as well as many of their names. Their seasonal migratory patterns interested him. About one visitor, "his wife & two companions were with him. They expect to go over to Ellesmere Land to hunt Nanook [bears]" (7 April). At the end of the season, the Inuit all departed and "told us that no more Innui will come up to Etah [this year]. The ice will be breaking up very soon & they have to prepare for a summer of kayaking at Robenson Bay" (16 May). Fitzsimmons documented the work of a budding Inuit aviation engineer: "Mac got Igdude to join the unbroken blade from the old propellor to what was left of this one. The rest of us, realizing Igdude's ignorance of aerodynamics, were afraid to look when he seized the saw & cut the propellor in two. But in the end he repaired it pretty well" (22 March). The crew sometimes supplied them with alcohol: "Some of the Inuit got a bit tight tonite. They are a riot in that condition. Two or three beers makes them happy without any unpleasantness. We never allow them to take more than three or four" (15 May).

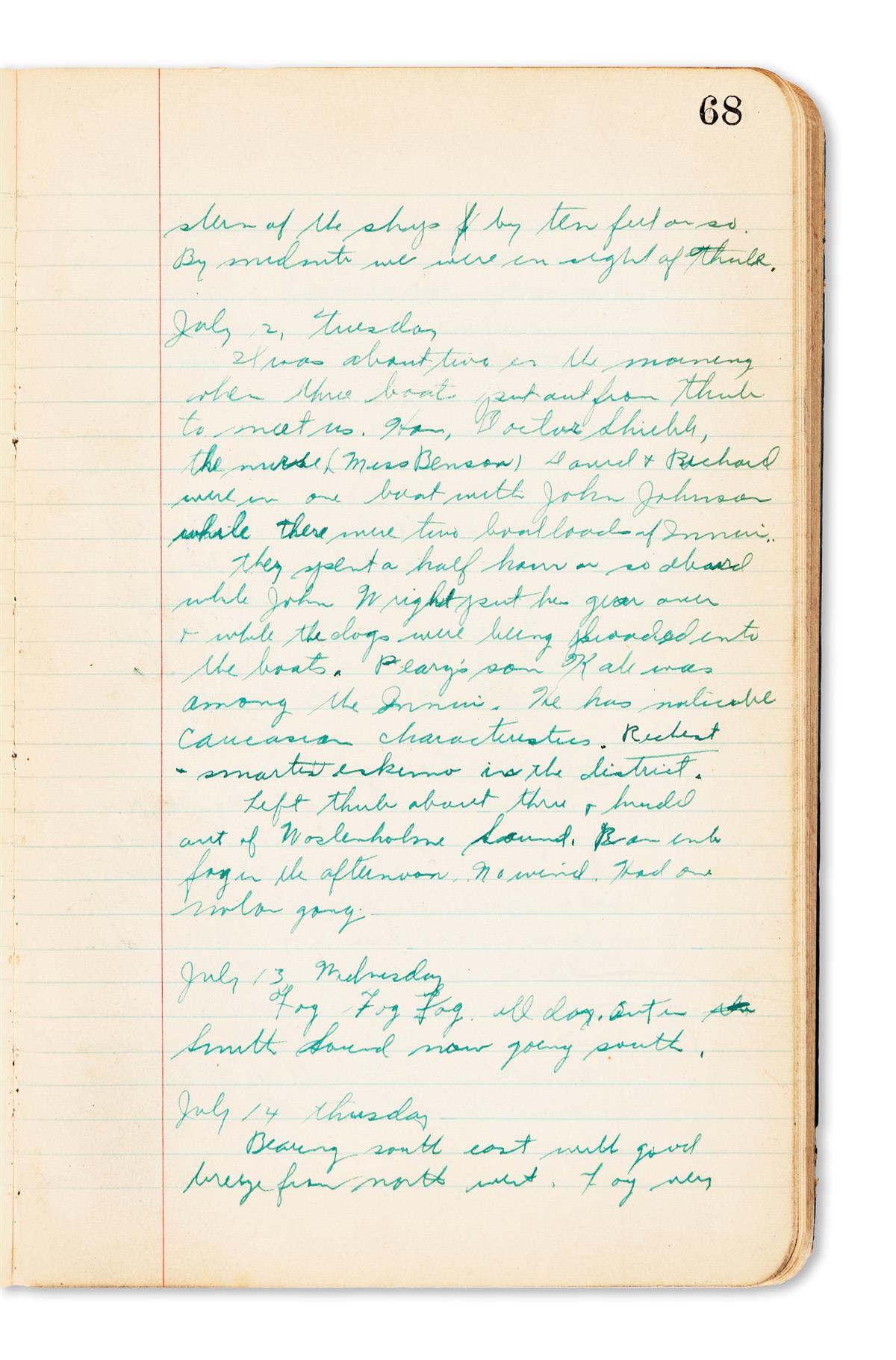

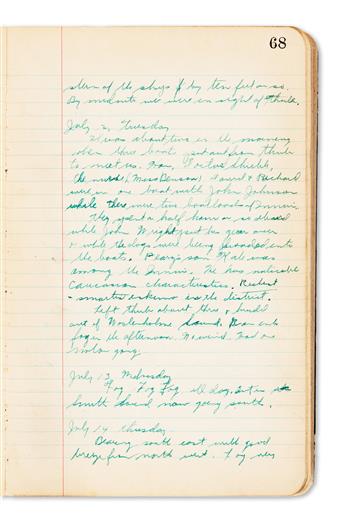

The explorer Robert Peary had made several extended visits to northern Grenland between 1886 and 1908, and loomed large in the imaginations of both the MacGregor Expedition and the local Inuit. Both Peary and his African-American lieutenant Matthew Henson had fathered children by local women. Fitzsimmons showed some reference books to a local: "Ootah went thru Peary's books this morning and pointed out to us pictures of his own father & mother, his wife's mother, and Peary's koona" (31 March). Fitzsimmons had his eyes open for these adult children, and apparently met two of them. On 15 June he met a party of 3 Inuit: "One of the Eskimos is definitely negroid--flaring nostrils, thick lips, kinky hair. We've decided he must be Matt Henson's son, though he does not know himself who his father was" (15 June). Two days later he provided the presumed son's name: "John & Ozusak, who by the way must be a son of Matt Henson's, brought back the pemmican." Henson's only son is generally thought to have been born in 1906, with the name Anauakaq. While en route home, the ship stopped in Thule (now Qaanaaq): "Peary's son Kali was among the Innui. He has noticeable Caucasian characteristics. Richest & smartest Eskimo in the district" (12 July). The existence of these sons was not generally known in the United States until 1951, so these diary entries provide important primary documentation on two elusive men of great interest.

The expedition was in spotty radio contact with civilization throughout. They were able to broadcast a radio interview with NBC on 21 May, and on 22 June they listened to American boxer Joe Louis defeat German Max Schmeling in a fight which captivated the world. The ship departed Foulk Fjord on 7 July, and the final three weeks of the diary describe a perilous journey through icebergs and dead ends as daylight slowly dwindled. On 21 July, "on Mac's watch they mosied along not knowing where they were going. They got the ship caught between two floes and were unable to move. . . . Made preparations for abandoning ship in case in the ice should crush it." The ship returned safely in October, long after the end of the diary.

At the rear of the volume are three pages of memorandum. John W. Wright, member of a British expedition which crossed their path, has signed with his address. The names of three Greenland villages are listed, including Siorpalok just south of Etah. Two lists of supplies are apparently for overland expeditions, including a "daily ration" list that includes 24 Baby Ruth bars.

Roy Fitzsimmons later served on Byrd's third Antarctica expedition, and then as a captain in the Army Air Force during World War Two, dying in a non-combat crash in May 1945. This diary is an important document of the MacGregor Arctic Expedition, and its intrepid and curious geophysicist. The passing references to the sons of Peary and Henson only add to its interest.

This diary was kept by LeRoy Gerald "Roy" Fitzsimmons (1915-1945), a recent Seton Hall College graduate from Newark, NJ, who served as the expedition's geophysicist and magnetologist. As with the other members of this small expedition, his actual duties were varied, ranging from cook to boat pilot as needed for basic survival. The diary begins several months into the expedition on 20 March 1938, with the approach of springtime after a long dark winter.

The expedition had its share of adventure and peril. While Fitzsimmons did not record his longer forays from the base camp, he did discuss his plans: "Fuzz & I have been planning a sledge trip to Cape Sabine. It depends upon supplies, especially dog pemmican. The trip has its dangers, inasmuch as the ice on Smith Sound is always on the move & very treacherous. Mac Millar in 1924 crossed in seven hours, while Kane 50 years ago required 31 days to make the trip" (4 April). He recorded a short expedition to gather cached gear on 15 May: "The seventeen dogs were at a full gallop a good part of the time, and going on the ice foot we were in constant danger of turning the sledge over or breaking a leg on the abutting rocks or countless pieces of rough ice." Because of the tide, "on the way up we had little trouble in getting on and off the ledge, but on the way back the sea ice was at least six feet below the ledge, and in order to get off we merely drove off on the fly."

The expedition's plane was piloted by Isaac "Ike" Schlossbach, whose life was often at risk. On 13 April, on take-off "the engine sputtered and for a few seconds it looked like curtains. But the engine caught and he continued his climb." The undercarriage was then crushed during the landing. Ike later took the plane for a survey of Inglefield Land further up the Greenland coast, but nearly ran out of fuel on the flight back to Etah: "As he taxied into the ship, the motor stopped several times from lack of gas. It was a close call, limping back the way he did. Ike seems to bear a charmed life" (22 May).

The expedition had frequent interactions with the local Inuit, who were either hired as laborers in camp, or would visit the camp for curiosity and sociability. Fitzsimmons was very friendly with the Inuit, making every effort to communicate and record his impressions, as well as many of their names. Their seasonal migratory patterns interested him. About one visitor, "his wife & two companions were with him. They expect to go over to Ellesmere Land to hunt Nanook [bears]" (7 April). At the end of the season, the Inuit all departed and "told us that no more Innui will come up to Etah [this year]. The ice will be breaking up very soon & they have to prepare for a summer of kayaking at Robenson Bay" (16 May). Fitzsimmons documented the work of a budding Inuit aviation engineer: "Mac got Igdude to join the unbroken blade from the old propellor to what was left of this one. The rest of us, realizing Igdude's ignorance of aerodynamics, were afraid to look when he seized the saw & cut the propellor in two. But in the end he repaired it pretty well" (22 March). The crew sometimes supplied them with alcohol: "Some of the Inuit got a bit tight tonite. They are a riot in that condition. Two or three beers makes them happy without any unpleasantness. We never allow them to take more than three or four" (15 May).

The explorer Robert Peary had made several extended visits to northern Grenland between 1886 and 1908, and loomed large in the imaginations of both the MacGregor Expedition and the local Inuit. Both Peary and his African-American lieutenant Matthew Henson had fathered children by local women. Fitzsimmons showed some reference books to a local: "Ootah went thru Peary's books this morning and pointed out to us pictures of his own father & mother, his wife's mother, and Peary's koona" (31 March). Fitzsimmons had his eyes open for these adult children, and apparently met two of them. On 15 June he met a party of 3 Inuit: "One of the Eskimos is definitely negroid--flaring nostrils, thick lips, kinky hair. We've decided he must be Matt Henson's son, though he does not know himself who his father was" (15 June). Two days later he provided the presumed son's name: "John & Ozusak, who by the way must be a son of Matt Henson's, brought back the pemmican." Henson's only son is generally thought to have been born in 1906, with the name Anauakaq. While en route home, the ship stopped in Thule (now Qaanaaq): "Peary's son Kali was among the Innui. He has noticeable Caucasian characteristics. Richest & smartest Eskimo in the district" (12 July). The existence of these sons was not generally known in the United States until 1951, so these diary entries provide important primary documentation on two elusive men of great interest.

The expedition was in spotty radio contact with civilization throughout. They were able to broadcast a radio interview with NBC on 21 May, and on 22 June they listened to American boxer Joe Louis defeat German Max Schmeling in a fight which captivated the world. The ship departed Foulk Fjord on 7 July, and the final three weeks of the diary describe a perilous journey through icebergs and dead ends as daylight slowly dwindled. On 21 July, "on Mac's watch they mosied along not knowing where they were going. They got the ship caught between two floes and were unable to move. . . . Made preparations for abandoning ship in case in the ice should crush it." The ship returned safely in October, long after the end of the diary.

At the rear of the volume are three pages of memorandum. John W. Wright, member of a British expedition which crossed their path, has signed with his address. The names of three Greenland villages are listed, including Siorpalok just south of Etah. Two lists of supplies are apparently for overland expeditions, including a "daily ration" list that includes 24 Baby Ruth bars.

Roy Fitzsimmons later served on Byrd's third Antarctica expedition, and then as a captain in the Army Air Force during World War Two, dying in a non-combat crash in May 1945. This diary is an important document of the MacGregor Arctic Expedition, and its intrepid and curious geophysicist. The passing references to the sons of Peary and Henson only add to its interest.

Exhibition Hours

Exhibition Hours

Aliquam vulputate ornare congue. Vestibulum maximus, libero in placerat faucibus, risus nisl molestie massa, ut maximus metus lectus vel lorem.