Sale 2615 - Lot 66

Price Realized: $ 7,500

Price Realized: $ 9,375

?Final Price Realized includes Buyer’s Premium added to Hammer Price

Estimate: $ 4,000 - $ 6,000

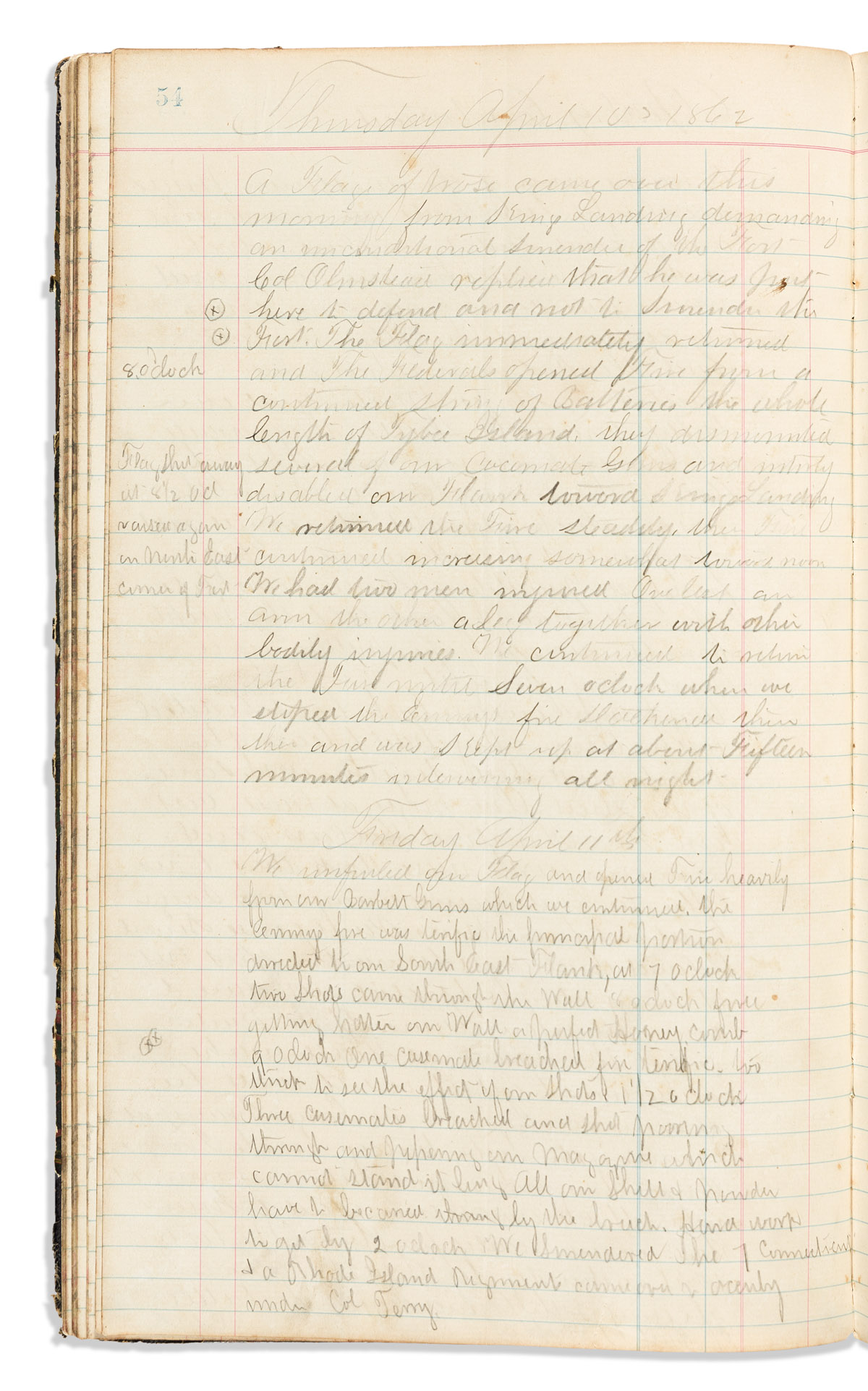

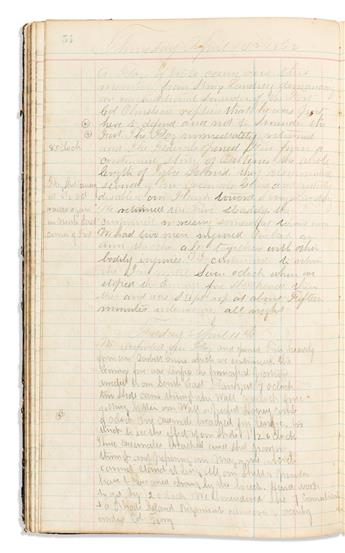

(CIVIL WAR--CONFEDERATE.) E.W. Drummond. Diary of a Maine transplant to Savannah, captured at Fort Pulaski and imprisoned in New York. 164 pages (160 of them manuscript diary pages). Folio, 13 x 8 inches, original 1/2 sheep over marbled boards, worn with front board nearly detached; several leaves torn from rear. Various places, 27 January to 13 September 1862

Additional Details

Edward William Drummond (1838-1876) was born and raised in Winslow, Maine. In 1859 he moved to Savannah, GA, where he worked as a bookkeeper and soon married a local girl. Secession soon presented him with a difficult decision. He sided with his wife's family and his adopted city, and joined the Chatham Artillery company as a sergeant in the Confederate service in August 1861. The company was stationed at the imposing Fort Pulaski, which guarded Savannah. The fort was an early target for a Federal offensive.

By the time this diary begins, Union artillery had nearly encircled Fort Pulaski, preparing to starve it into submission. Supply vessels were still managing to sneak through under heavy artillery fire. Drummond noted on 31 January: "I have been at work all day making a store room. We now have about one year's full rations for the garrison." Their telegraph cable was cut on 12 February, and the last supply steamer made it through the bombardment two days later. On 17 February he wrote "Here we are, cut off and likely to stay so." Four days later he noted "Tomorrow our Congress meets to sign the declaration of our independence, and the foundation of a permanent government." From this point onward, contact with the outside world was limited to an occasional boat sneaking through with mail, and of course constant observation of Savannah and nearby troops. 15 March was an exciting day: "We have had quite an advent today for us. Two White men and three Negroes came over through a creek from Wilmington Island, bringing with them four beeves, which are quite acceptable." The next day, "our beef friends probably got back safe as they displayed the given signal from Wilmington Island." On 18 March he noted proudly "Our old Merrimack or Virginia as she is now called has been doing great damage among the Federal Navy, which we trust is but a beginning."

On 10 April, the Union troops requested the fort's surrender, which was refused. In the ensuing bombardment, "we had two men injured. One lost an arm, the other a leg, together with other bodily injuries." The next day Drummond offered regular updates. "8 o'clock, fire getting hotter. Our wall a perfect honey comb. . . . 1 1/2 o'clock, three casemates breached and shot pouring through and pepering our magazine, which cannot stand it long. . . . 2 o'clock, we surrendered. The 7 Connecticut and a Rhode Island regiment came over to occupy under Col. Terry." The fort's defenders were made prisoners of war, and on 22 April Drummond arrived at his new home, the prisoner camp at Governors Island in New York Harbor.

Drummond, who as a clerk sergeant was placed with the officers, gave Governor's Island good reviews. The prisoners were allowed to move freely about the island, and were permitted some communication with civilians in the city: "We could not have chosen a better place for imprisonment if we had made our own selection" (24 April). The prisoners had brought their enslaved servants with them. On 4 May, and order came for "all our Negro boys to be sent to New York and turned loose in the city. We all feel that it is hard and unmerciful. . . . They know no one, and will fare hard, poor fellows. . . . Unaccustomed to such treatment they had almost rather starve." On 28 May Drummond describes the prison newspaper, "Dixie Discourses," and two days later "we had our usual game of ball this morning. They are becoming quite exciting. All are improving in the science of the game and the sides are standing on equal terms." Hopes of an exchange were dashed on 19 June as Drummond and the officers were transferred to the prison at Johnson's Island in Lake Erie, off the coast of Ohio. On 21 June he made a crude sketch of the barrack arrangements. Baseball was resumed by 18 July. On 8 August a prisoner from Arkansas was shot by a guard for no apparent reason. On 10 August the guards pasted up broadsides offering freedom to prisoners who took the oath of allegiance, which was accepted by only one or two men: "The Yankees seem surprised that their flaming announcement is not more fully appreciated." Drummond was exchanged on 31 August and set off for the South. The young man from Maine wrote on 9 September: "Ho for Dixie. We shall soon be among our people." The diary comes to a close on 13 September as his steamer passed through Arkansas. The historical record shows that Drummond rejoined the 1st Georgia Infantry, served as a defender of Fort Wagner in South Carolina, was wounded at the Battle of Dalton, but survived the war and returned to Savannah.

This exceptional diary was published in its entirety in "A Confederate Yankee: The Journal of Edward William Drummond, a Confederate Soldier from Maine," edited by Roger S. Durham (Knoxville, TN: University of Tennessee Press, 2004). Provenance: by descent to Edward William Drummond's great-granddaughter as described in the "Confederate Yankee" acknowledgements in 2004; thence into the trade.

WITH--a Bible printed by the American Bible Society in 1861, inscribed on the front free endpaper "E.W. Drummond, presented to him on the 27th day of April 1862, his first Sabbath on Governor's Island as a prisoner of war."

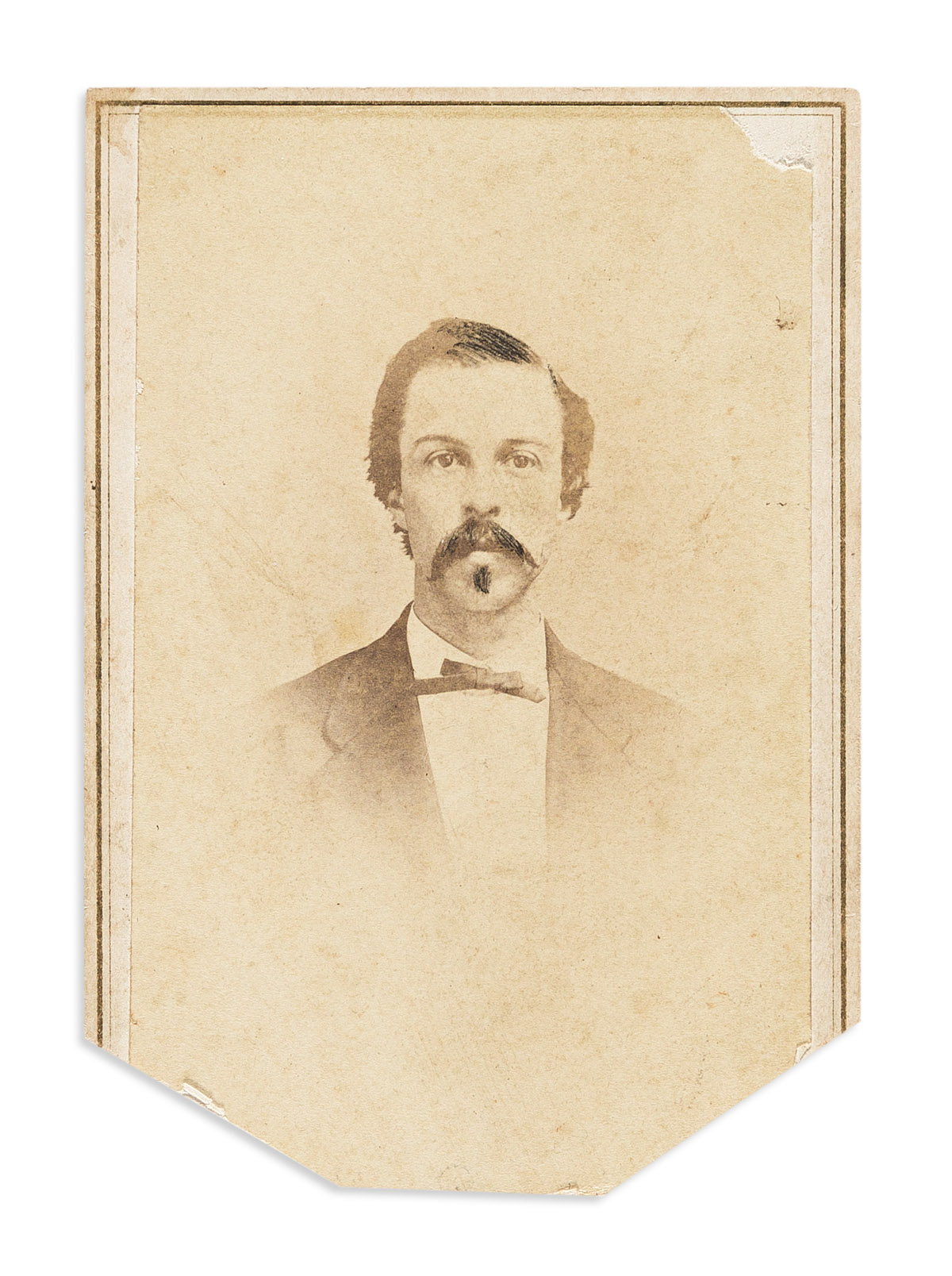

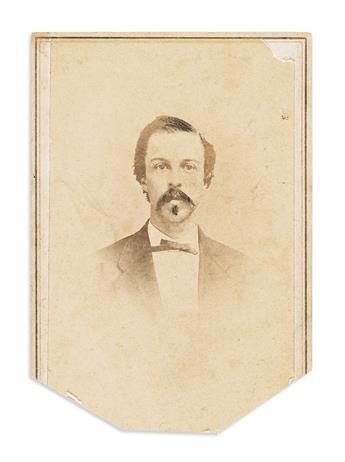

Carte-de-visite photograph of Drummond, clipped at bottom edge, slightly retouched, with backmark of D.J. Ryan of Savannah, GA, circa 1859-1860 (published in "A Confederate Yankee," page xxvi).

An early transcript of an 1864 Savannah newspaper article on wounds suffered by Drummond in battle (transcribed in "Confederate Yankee," page 152).

A packet of 11 newspaper clippings and pamphlets on Fort Pulaski and related topics, 1913-1961. One of the pamphlets is annotated "I was quite a curio to the crowd of visitors when they learned I was the son of one of Pulaski's defenders."

2 related letters to Drummond descendants, 1974 and 2000, and a copy of "Confederate Yankee" warmly inscribed by the editor to the then-owner of the diary.

By the time this diary begins, Union artillery had nearly encircled Fort Pulaski, preparing to starve it into submission. Supply vessels were still managing to sneak through under heavy artillery fire. Drummond noted on 31 January: "I have been at work all day making a store room. We now have about one year's full rations for the garrison." Their telegraph cable was cut on 12 February, and the last supply steamer made it through the bombardment two days later. On 17 February he wrote "Here we are, cut off and likely to stay so." Four days later he noted "Tomorrow our Congress meets to sign the declaration of our independence, and the foundation of a permanent government." From this point onward, contact with the outside world was limited to an occasional boat sneaking through with mail, and of course constant observation of Savannah and nearby troops. 15 March was an exciting day: "We have had quite an advent today for us. Two White men and three Negroes came over through a creek from Wilmington Island, bringing with them four beeves, which are quite acceptable." The next day, "our beef friends probably got back safe as they displayed the given signal from Wilmington Island." On 18 March he noted proudly "Our old Merrimack or Virginia as she is now called has been doing great damage among the Federal Navy, which we trust is but a beginning."

On 10 April, the Union troops requested the fort's surrender, which was refused. In the ensuing bombardment, "we had two men injured. One lost an arm, the other a leg, together with other bodily injuries." The next day Drummond offered regular updates. "8 o'clock, fire getting hotter. Our wall a perfect honey comb. . . . 1 1/2 o'clock, three casemates breached and shot pouring through and pepering our magazine, which cannot stand it long. . . . 2 o'clock, we surrendered. The 7 Connecticut and a Rhode Island regiment came over to occupy under Col. Terry." The fort's defenders were made prisoners of war, and on 22 April Drummond arrived at his new home, the prisoner camp at Governors Island in New York Harbor.

Drummond, who as a clerk sergeant was placed with the officers, gave Governor's Island good reviews. The prisoners were allowed to move freely about the island, and were permitted some communication with civilians in the city: "We could not have chosen a better place for imprisonment if we had made our own selection" (24 April). The prisoners had brought their enslaved servants with them. On 4 May, and order came for "all our Negro boys to be sent to New York and turned loose in the city. We all feel that it is hard and unmerciful. . . . They know no one, and will fare hard, poor fellows. . . . Unaccustomed to such treatment they had almost rather starve." On 28 May Drummond describes the prison newspaper, "Dixie Discourses," and two days later "we had our usual game of ball this morning. They are becoming quite exciting. All are improving in the science of the game and the sides are standing on equal terms." Hopes of an exchange were dashed on 19 June as Drummond and the officers were transferred to the prison at Johnson's Island in Lake Erie, off the coast of Ohio. On 21 June he made a crude sketch of the barrack arrangements. Baseball was resumed by 18 July. On 8 August a prisoner from Arkansas was shot by a guard for no apparent reason. On 10 August the guards pasted up broadsides offering freedom to prisoners who took the oath of allegiance, which was accepted by only one or two men: "The Yankees seem surprised that their flaming announcement is not more fully appreciated." Drummond was exchanged on 31 August and set off for the South. The young man from Maine wrote on 9 September: "Ho for Dixie. We shall soon be among our people." The diary comes to a close on 13 September as his steamer passed through Arkansas. The historical record shows that Drummond rejoined the 1st Georgia Infantry, served as a defender of Fort Wagner in South Carolina, was wounded at the Battle of Dalton, but survived the war and returned to Savannah.

This exceptional diary was published in its entirety in "A Confederate Yankee: The Journal of Edward William Drummond, a Confederate Soldier from Maine," edited by Roger S. Durham (Knoxville, TN: University of Tennessee Press, 2004). Provenance: by descent to Edward William Drummond's great-granddaughter as described in the "Confederate Yankee" acknowledgements in 2004; thence into the trade.

WITH--a Bible printed by the American Bible Society in 1861, inscribed on the front free endpaper "E.W. Drummond, presented to him on the 27th day of April 1862, his first Sabbath on Governor's Island as a prisoner of war."

Carte-de-visite photograph of Drummond, clipped at bottom edge, slightly retouched, with backmark of D.J. Ryan of Savannah, GA, circa 1859-1860 (published in "A Confederate Yankee," page xxvi).

An early transcript of an 1864 Savannah newspaper article on wounds suffered by Drummond in battle (transcribed in "Confederate Yankee," page 152).

A packet of 11 newspaper clippings and pamphlets on Fort Pulaski and related topics, 1913-1961. One of the pamphlets is annotated "I was quite a curio to the crowd of visitors when they learned I was the son of one of Pulaski's defenders."

2 related letters to Drummond descendants, 1974 and 2000, and a copy of "Confederate Yankee" warmly inscribed by the editor to the then-owner of the diary.

Exhibition Hours

Exhibition Hours

Aliquam vulputate ornare congue. Vestibulum maximus, libero in placerat faucibus, risus nisl molestie massa, ut maximus metus lectus vel lorem.