Sale 2687 - Lot 86

Price Realized: $ 4,600

Price Realized: $ 5,750

?Final Price Realized includes Buyer’s Premium added to Hammer Price

Estimate: $ 2,000 - $ 3,000

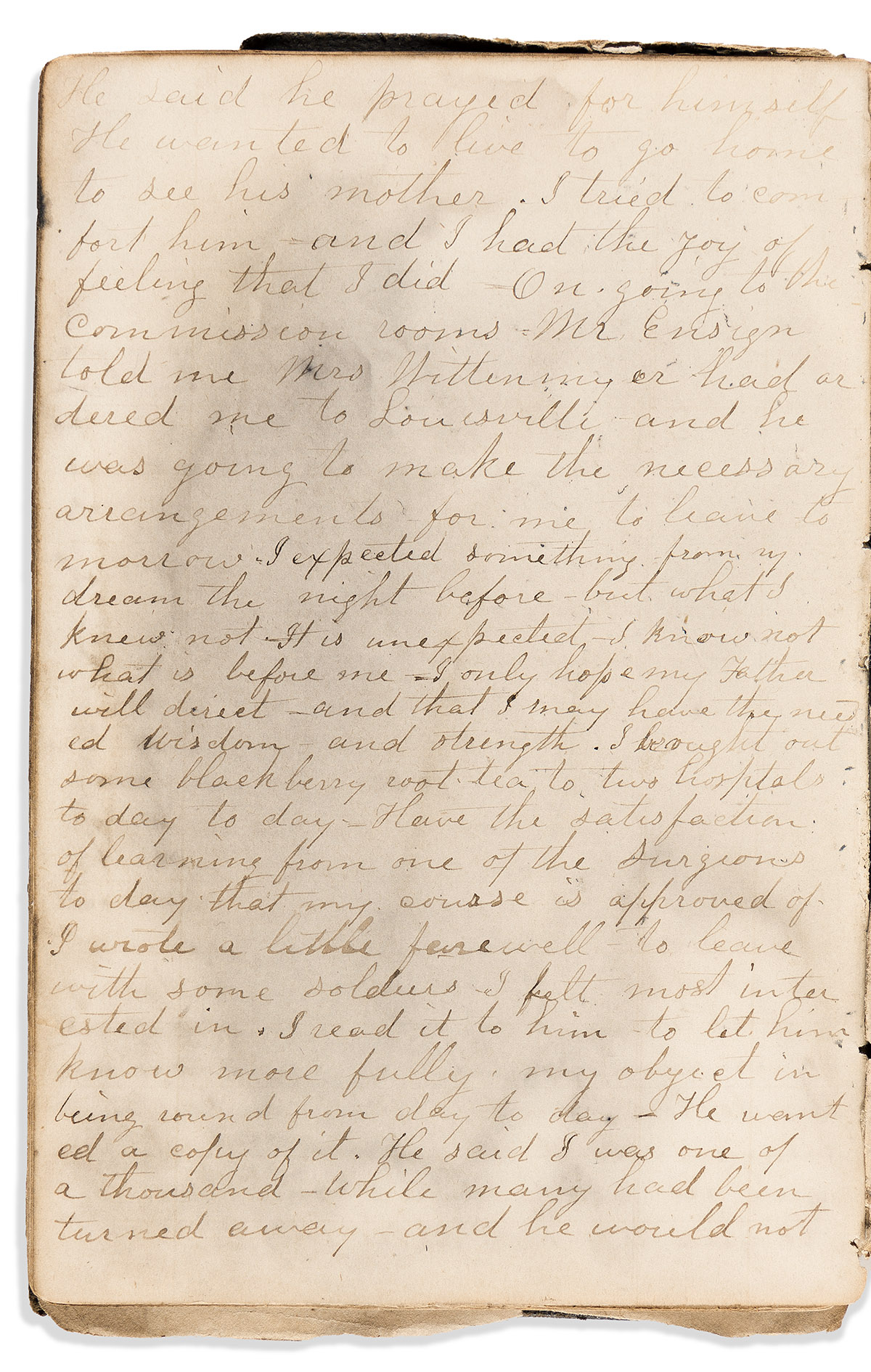

(CIVIL WAR--IOWA.) Catherine Colver Williams. Diary of a Shell Rock woman searching for her soldier son. [60] manuscript diary pages, plus [49] pages of later memoranda through 1877. 12mo, original calf, worn and coming disbound; some leaves loose, dampstaining and minor wear, all diary pages present and legible, though faint in spots. Various places, 6 October to 16 December 1864

Additional Details

"Bade adieu to my dear children and started for the Army" is the first entry in this haunting diary.

Catherine Colver Williams (1816-1897) was living in Shell Rock, Iowa when the war broke out. Her oldest son William Henry Williams (1846-1869) enlisted with the 32nd Iowa Infantry, Company E in January 1864. The regiment saw heavy duty on the Red River Campaign and the Battle of Tupelo. When she failed to hear from William, Catherine resolved to head to the front lines to learn his fate, leaving her husband to care for their younger children in Iowa.

Securing passes to travel near the front lines was difficult. Her plan hinged upon working for Sarah "Annie" Turner Wittenmyer (1827-1900), the famed Iowa Sanitary Commission agent who did so much for the state's soldiers during the war, and was at this point developing hospital kitchens nationally with the United States Christian Commission. An avowed abolitionist and believer in the Union cause, Williams also wanted to see the war with her own eyes, and was keenly interested in the perspectives of both the formerly enslaved and their former owners.

The initial pages of this diary trace the journey of Catherine Williams east to Dubuque and down the Mississippi. In St. Louis she stays at the famed Barnum Hotel and visits the Christian Commission, where she records a long conversation with the woman running the kitchen, who had escaped from slavery: "What made you come away? Why would you rather stay and work for nothing but your clothes and not many at that and hardly enough to eat, and be bought and sold like dumb beasts by white folks?" On the steamer to Cairo, she chats with a slave-owning Missouri woman who hoped McClellan would be elected president to restore "the Union as it was . . . she would have her slaves."

From Cairo she headed up the Ohio River to Memphis. While a pianist performs on board, she notices that "one woman of about my age takes no interest in what is going on. I just learned she is on her way to visit or see a son sick in the hospital at Memphis. Don't know whether she will find him dead or alive. That tells the tale. Where is my boy? I do not forget why I left my darlings" (15 October). The next day in Memphis, she visited a hospital to "see if something would not suggest itself whereby I could make myself useful till Mrs. Wittenmyer returned." On the 18th, "I have very discouraging reports of Mrs. Wittenmyer and her undertaking. . . . I am a dupe among dupes. Well, I must see if so," but the next day a hospital matron assured her: "Mrs. Wit. is sustained and defended, and I am told not to fear." She noted that "one ward contains nothing but Negroes, some of whom were wounded at the fight at Tupelo. One quite aged Negro sat by the stove with his spelling book, pointing with his finger like a child, studying a spelling lesson. . . . They seemed to think they were quite honored in fighting for a country which would own them as men."

On 20 October, she had a long chat with Captain Henry C. Brown of the 60th United States Colored Troops, who recounted his regiment's heroic escape from a larger Confederate force: they "marched out of Helena Arkansas last summer to obtain supplies and when 22 miles out, were surrounded nearly by Rebs, when they fought 5 hours, killing about as many as their whole force when they retreated, and fought their way back again. . . . His mother's associates were such women as Frances Gage, Lucy Stone Blackwell &c."

She began volunteering at the hospital, seeing some patients recovering and "on some however death has set his seal. O for the power to relieve. I think of my own soldier son and wonder where he is and how" (26 October). On 1 November she received her first useful clue: "Saw a young man belonging to the 32nd Iowa, Spencer Crosby by name. He said the 32nd were at Jefferson Barracks."

On 12 November she attended a wedding: "Came to find out Uncle Morris was going to be married and another real old gray-bearded Negro who had come in from somewhere. They had long lived with their women slave-fashion, but now as they could do it, they wanted to be married according to the laws of the land. . . . With the joy of youth depicted upon their dark countenances as though they were just beginning life, and with expressions of gratitude for having lived to see the day, they received the congratulations of all spectators" (12 November).

On 15 November, she received orders from Mrs. Wittenmyer to report to Louisville. At the same time, she learned that General A.J. Smith's XVI Corps, including her son's 32nd Iowa, would be passing through Paducah, KY en route to Louisville. In violation of her pass and orders, she debarked from her steamer on Paducah on 19 November: "I hope I may be pardoned if I have erred, though I should be willing to endure considerable to see or even hear from my boy." With no sign of the 32nd Iowa, she went onward to Louisville two days later. On 3 December she completed her secondary quest: "A lady in black came in which as I suspected was Mrs. Wittmyer. After service, was introduced to her. . . . We had quite a lengthy chat. She asked questions and I explained what I could do and what not, about teaching the Bible &c." She was assigned to work in the Brown Hospital 4 miles out of town: "Visiting the sick, writing letters for them, contriving up one thing after another for convalescents to amuse and instruct and interest them withal keeps my brain busy. . . . Must try to write a letter, but I do not get any. Am I never to hear from my dear boy again?" (8 December).

The diary ends inconclusively on 16 December with the words "The more I do, the more I want to." The records do show that her son William remained with the 32nd Iowa until they were mustered out in July 1865; he then re-enlisted with the 8th United States Infantry through 1866.

We have not yet puzzled out why Mrs. Williams was so alarmed that she went off across the country in pursuit of her son. The family moved to Bates County, Missouri shortly after the war, where son William was buried at the age of 23 in 1869. As a widow, she brought her surviving children to Colorado by wagon in 1876 (Elbert County Tribune, 24 June 1909). She presented a petition for women's suffrage from Indianapolis, Colorado in 1889 (see the Washington Evening Star of 10 January 1889) and died in Colorado in 1897.

The diary is not signed, but family provenance suggests the authorship, which is supported in several places by the content: the travel itinerary begins west of Dubuque, Iowa; the author describes herself as Mrs. Williams on 16 November, and often mentions her young children at home; he mentions her son's regiment as the 32nd Iowa on 1 November. She recounts an incident from her service in the Christian Commission, corroborated by the events of this diary, in the Washington National Tribune of 13 February 1896.

Provenance: Catherine Colver Williams to her younger son Cyrus Williams (1858-1944), who is often referenced in the diary; his son Henry Kirk Williams (1878-1953); to his grandson; and thence consigned by the family.

This stained and battered diary is not much to look at, and the author is not an historical figure of any note. Judged on its content and its literary qualities, though, it is one of the best civilian diaries of the Civil War we have ever encountered, and well worthy of publication. Her empathy, descriptive powers, and the scenes she encountered have the effect of watching a poignant film.

Catherine Colver Williams (1816-1897) was living in Shell Rock, Iowa when the war broke out. Her oldest son William Henry Williams (1846-1869) enlisted with the 32nd Iowa Infantry, Company E in January 1864. The regiment saw heavy duty on the Red River Campaign and the Battle of Tupelo. When she failed to hear from William, Catherine resolved to head to the front lines to learn his fate, leaving her husband to care for their younger children in Iowa.

Securing passes to travel near the front lines was difficult. Her plan hinged upon working for Sarah "Annie" Turner Wittenmyer (1827-1900), the famed Iowa Sanitary Commission agent who did so much for the state's soldiers during the war, and was at this point developing hospital kitchens nationally with the United States Christian Commission. An avowed abolitionist and believer in the Union cause, Williams also wanted to see the war with her own eyes, and was keenly interested in the perspectives of both the formerly enslaved and their former owners.

The initial pages of this diary trace the journey of Catherine Williams east to Dubuque and down the Mississippi. In St. Louis she stays at the famed Barnum Hotel and visits the Christian Commission, where she records a long conversation with the woman running the kitchen, who had escaped from slavery: "What made you come away? Why would you rather stay and work for nothing but your clothes and not many at that and hardly enough to eat, and be bought and sold like dumb beasts by white folks?" On the steamer to Cairo, she chats with a slave-owning Missouri woman who hoped McClellan would be elected president to restore "the Union as it was . . . she would have her slaves."

From Cairo she headed up the Ohio River to Memphis. While a pianist performs on board, she notices that "one woman of about my age takes no interest in what is going on. I just learned she is on her way to visit or see a son sick in the hospital at Memphis. Don't know whether she will find him dead or alive. That tells the tale. Where is my boy? I do not forget why I left my darlings" (15 October). The next day in Memphis, she visited a hospital to "see if something would not suggest itself whereby I could make myself useful till Mrs. Wittenmyer returned." On the 18th, "I have very discouraging reports of Mrs. Wittenmyer and her undertaking. . . . I am a dupe among dupes. Well, I must see if so," but the next day a hospital matron assured her: "Mrs. Wit. is sustained and defended, and I am told not to fear." She noted that "one ward contains nothing but Negroes, some of whom were wounded at the fight at Tupelo. One quite aged Negro sat by the stove with his spelling book, pointing with his finger like a child, studying a spelling lesson. . . . They seemed to think they were quite honored in fighting for a country which would own them as men."

On 20 October, she had a long chat with Captain Henry C. Brown of the 60th United States Colored Troops, who recounted his regiment's heroic escape from a larger Confederate force: they "marched out of Helena Arkansas last summer to obtain supplies and when 22 miles out, were surrounded nearly by Rebs, when they fought 5 hours, killing about as many as their whole force when they retreated, and fought their way back again. . . . His mother's associates were such women as Frances Gage, Lucy Stone Blackwell &c."

She began volunteering at the hospital, seeing some patients recovering and "on some however death has set his seal. O for the power to relieve. I think of my own soldier son and wonder where he is and how" (26 October). On 1 November she received her first useful clue: "Saw a young man belonging to the 32nd Iowa, Spencer Crosby by name. He said the 32nd were at Jefferson Barracks."

On 12 November she attended a wedding: "Came to find out Uncle Morris was going to be married and another real old gray-bearded Negro who had come in from somewhere. They had long lived with their women slave-fashion, but now as they could do it, they wanted to be married according to the laws of the land. . . . With the joy of youth depicted upon their dark countenances as though they were just beginning life, and with expressions of gratitude for having lived to see the day, they received the congratulations of all spectators" (12 November).

On 15 November, she received orders from Mrs. Wittenmyer to report to Louisville. At the same time, she learned that General A.J. Smith's XVI Corps, including her son's 32nd Iowa, would be passing through Paducah, KY en route to Louisville. In violation of her pass and orders, she debarked from her steamer on Paducah on 19 November: "I hope I may be pardoned if I have erred, though I should be willing to endure considerable to see or even hear from my boy." With no sign of the 32nd Iowa, she went onward to Louisville two days later. On 3 December she completed her secondary quest: "A lady in black came in which as I suspected was Mrs. Wittmyer. After service, was introduced to her. . . . We had quite a lengthy chat. She asked questions and I explained what I could do and what not, about teaching the Bible &c." She was assigned to work in the Brown Hospital 4 miles out of town: "Visiting the sick, writing letters for them, contriving up one thing after another for convalescents to amuse and instruct and interest them withal keeps my brain busy. . . . Must try to write a letter, but I do not get any. Am I never to hear from my dear boy again?" (8 December).

The diary ends inconclusively on 16 December with the words "The more I do, the more I want to." The records do show that her son William remained with the 32nd Iowa until they were mustered out in July 1865; he then re-enlisted with the 8th United States Infantry through 1866.

We have not yet puzzled out why Mrs. Williams was so alarmed that she went off across the country in pursuit of her son. The family moved to Bates County, Missouri shortly after the war, where son William was buried at the age of 23 in 1869. As a widow, she brought her surviving children to Colorado by wagon in 1876 (Elbert County Tribune, 24 June 1909). She presented a petition for women's suffrage from Indianapolis, Colorado in 1889 (see the Washington Evening Star of 10 January 1889) and died in Colorado in 1897.

The diary is not signed, but family provenance suggests the authorship, which is supported in several places by the content: the travel itinerary begins west of Dubuque, Iowa; the author describes herself as Mrs. Williams on 16 November, and often mentions her young children at home; he mentions her son's regiment as the 32nd Iowa on 1 November. She recounts an incident from her service in the Christian Commission, corroborated by the events of this diary, in the Washington National Tribune of 13 February 1896.

Provenance: Catherine Colver Williams to her younger son Cyrus Williams (1858-1944), who is often referenced in the diary; his son Henry Kirk Williams (1878-1953); to his grandson; and thence consigned by the family.

This stained and battered diary is not much to look at, and the author is not an historical figure of any note. Judged on its content and its literary qualities, though, it is one of the best civilian diaries of the Civil War we have ever encountered, and well worthy of publication. Her empathy, descriptive powers, and the scenes she encountered have the effect of watching a poignant film.

Exhibition Hours

Exhibition Hours

Aliquam vulputate ornare congue. Vestibulum maximus, libero in placerat faucibus, risus nisl molestie massa, ut maximus metus lectus vel lorem.