Sale 2687 - Lot 92

Price Realized: $ 5,600

Price Realized: $ 7,000

?Final Price Realized includes Buyer’s Premium added to Hammer Price

Estimate: $ 1,200 - $ 1,800

(CIVIL WAR--MEDICINE.) W. Everett Clark. Diary of a Civil War hospital worker, describing Lincoln, contrabands and more. [158] manuscript pages, 8 x 5 inches, on 42 unbound folding sheets; minimal wear. City Point, VA and elsewhere, 1864-1865

Additional Details

William Everett Clark (1838-1912) was raised in rural Oneida County, NY, youngest son of industrialist Erastus Clark. In 1863, he was living in Queens County on Long Island, where he enlisted as a private in the 15th New York Heavy Artillery; his soldiering diary was sold by Swann last year. By the time of this diary, he was a clerk in the V Corps hospital near City Point, VA, where he was a frequent witness to the carnage. Not far from the front lines before Richmond, distant shelling and rockets were often impossible to ignore at the hospital. His diary extends from 20 October 1864 until he left the service in June.

Clark was sometimes called away from his desk to help out in the hospital, such as on 19 March 1865: "Doing the work for two or three, and acting as nurse." He was thus able to appreciate the difficulty of the work. On 8 November 1864 he noted that "We are again having lady nurses among us, sent here by Miss Dix." On 28 March 1865, he noted "Many of the wards in our hospitals are worth a journey of a hundred miles to see. The nurses have worked industriously, and the wards are trained very splendidly." The scenes were often gruesome. Even battle-hardened General John Gibbon, who had been wounded at Gettysburg, "visited the dissecting room, but could not endure the sights long" (23 January 1865).

Though Clark was a combat veteran himself and had seen many horrifying hospital scenes, the military executions he witnessed seemed to shake him the most: "Witnessed the hanging of a deserter. It was a sad sight, but no doubt a matter of justice. I should judge the affair was witnessed by about 6000 soldiers formed into a double square with the gallows in the center. . . . At the tap of a drum he was launched into eternity" (27 January 1865). "I stepped up to the place of execution and witnessed the heart-sickening scene of the shooting of two spys. I have now seen all the human killing I ever care to. One of them lingered some ten minutes after being shot before dying" (18 March 1865).

Clark took particular interest in the "contrabands" who had escaped from slavery and congregated near City Point. As a clerk, it was his job to conduct periodic censuses (including one on the first day of the diary), but he also attended a wedding shortly after the close of fighting: "I went down to the contraband camp to witness the marriage of twelve couple of contrabands. A very interesting affair. Many of the couples had lived together for many years without the usual ceremonies of marriage, and three couples at least were over sixty years of age."

Clark saw President Lincoln up close on two occasions in April 1865, shortly before the assassination, and was impressed by his unpretentious manner. On 2 April, while visiting the breastworks near the hospital, "we came almost in contact with 'Uncle Abraham,' who looked much worn, and the party accompanying him consisting of Captain Strang, Col. Ruggles and Admiral Porter. I sat and watched the old boy's movements for nearly an hour and was much interested in what Johnny Bull would call his 'undignified' acts. He even sat flat down on the floor near the cannon while he looked through his glass. And I saw him laugh very heartily 'before folk,' a very undignified proceeding. Why not?" Eight days later, "About noon, the President, wife, Charles Sumner, and others arrived. The President spent several hours in shaking hands with patients and convalescents."

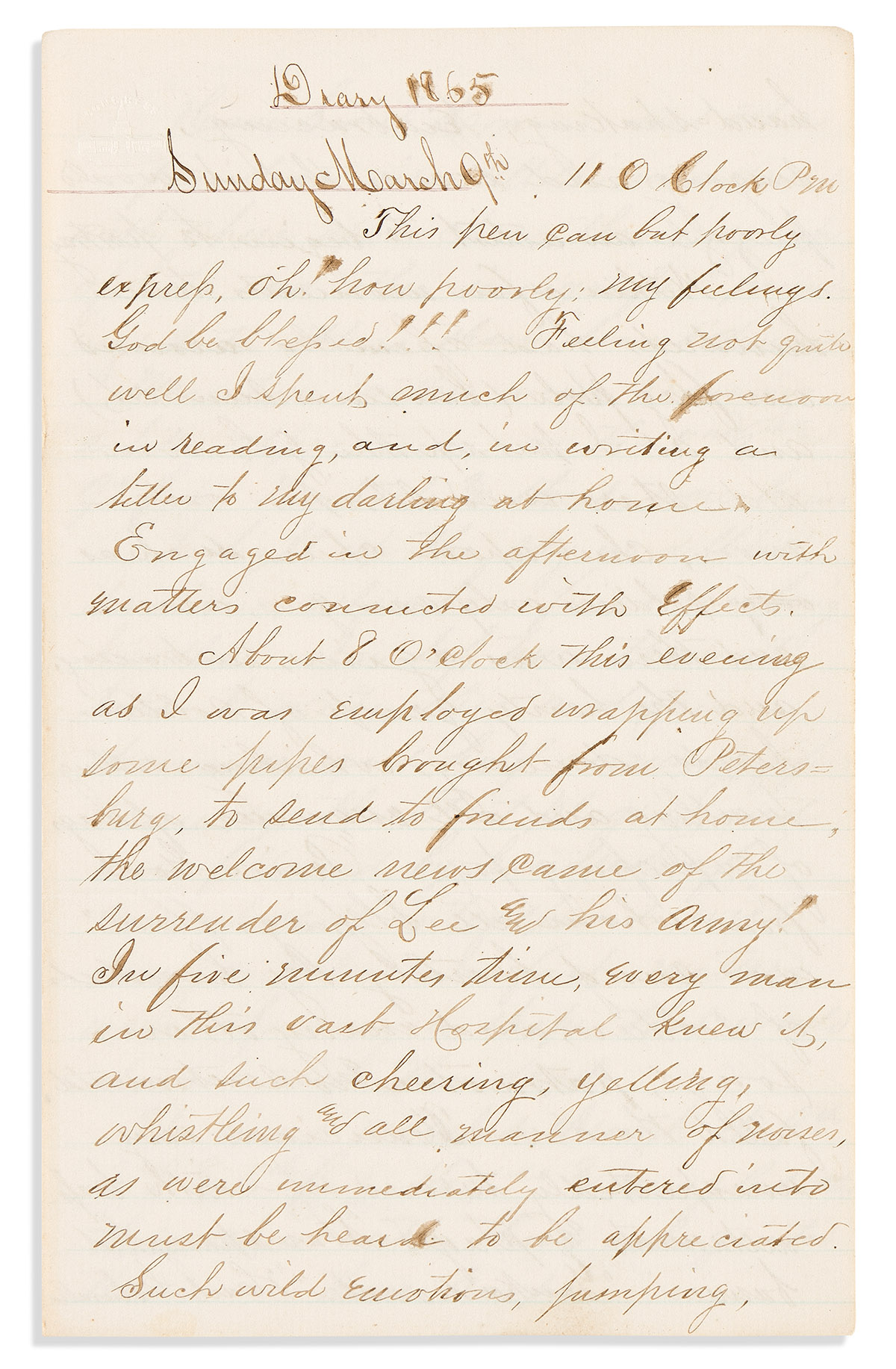

Clark's longest and certainly happiest entry was on 9 April 1865 (misdated as March): "The welcome news came of the surrender of Lee and his army! In five minutes' time, every man in this vast hospital knew it, and such cheering, yelling, whistling and all manner of noises as were immediately entered into must be heard to be appreciated. . . . Within a few minutes' time, hundreds had assembled around our flagpole, bare since sunset, and as I put up the glorious old Stars and Stripes once more, cheer upon cheer such as only soldiers can give, arose."

Of course, a week later the mood shifted. Civil War diaries are sometimes like multiple versions of a novel with the same plot, written by thousands of different authors. Clark discusses the assassination at length, noting that one of the hospital's Confederate patients did not share in the sorrow: "One Johnny who expressed his pleasure at the President's death would have been strung up in double-quick time had he not been rescued by the guards and taken to the Provost Marshall's."

More diary details available upon request. With--11 related hospital administration documents addressed to Clark or the supervising surgeon William Lyman Faxon, including a letter describing the status of three patients who underwent secondary amputations; an official order on embalming services; an order to prepare for an influx of new patients from Petersburg; and a schedule for the auction of "the effects of deceased soldiers, consisting of clothing, watches, and other valuables," 24 March 1865.

Clark was sometimes called away from his desk to help out in the hospital, such as on 19 March 1865: "Doing the work for two or three, and acting as nurse." He was thus able to appreciate the difficulty of the work. On 8 November 1864 he noted that "We are again having lady nurses among us, sent here by Miss Dix." On 28 March 1865, he noted "Many of the wards in our hospitals are worth a journey of a hundred miles to see. The nurses have worked industriously, and the wards are trained very splendidly." The scenes were often gruesome. Even battle-hardened General John Gibbon, who had been wounded at Gettysburg, "visited the dissecting room, but could not endure the sights long" (23 January 1865).

Though Clark was a combat veteran himself and had seen many horrifying hospital scenes, the military executions he witnessed seemed to shake him the most: "Witnessed the hanging of a deserter. It was a sad sight, but no doubt a matter of justice. I should judge the affair was witnessed by about 6000 soldiers formed into a double square with the gallows in the center. . . . At the tap of a drum he was launched into eternity" (27 January 1865). "I stepped up to the place of execution and witnessed the heart-sickening scene of the shooting of two spys. I have now seen all the human killing I ever care to. One of them lingered some ten minutes after being shot before dying" (18 March 1865).

Clark took particular interest in the "contrabands" who had escaped from slavery and congregated near City Point. As a clerk, it was his job to conduct periodic censuses (including one on the first day of the diary), but he also attended a wedding shortly after the close of fighting: "I went down to the contraband camp to witness the marriage of twelve couple of contrabands. A very interesting affair. Many of the couples had lived together for many years without the usual ceremonies of marriage, and three couples at least were over sixty years of age."

Clark saw President Lincoln up close on two occasions in April 1865, shortly before the assassination, and was impressed by his unpretentious manner. On 2 April, while visiting the breastworks near the hospital, "we came almost in contact with 'Uncle Abraham,' who looked much worn, and the party accompanying him consisting of Captain Strang, Col. Ruggles and Admiral Porter. I sat and watched the old boy's movements for nearly an hour and was much interested in what Johnny Bull would call his 'undignified' acts. He even sat flat down on the floor near the cannon while he looked through his glass. And I saw him laugh very heartily 'before folk,' a very undignified proceeding. Why not?" Eight days later, "About noon, the President, wife, Charles Sumner, and others arrived. The President spent several hours in shaking hands with patients and convalescents."

Clark's longest and certainly happiest entry was on 9 April 1865 (misdated as March): "The welcome news came of the surrender of Lee and his army! In five minutes' time, every man in this vast hospital knew it, and such cheering, yelling, whistling and all manner of noises as were immediately entered into must be heard to be appreciated. . . . Within a few minutes' time, hundreds had assembled around our flagpole, bare since sunset, and as I put up the glorious old Stars and Stripes once more, cheer upon cheer such as only soldiers can give, arose."

Of course, a week later the mood shifted. Civil War diaries are sometimes like multiple versions of a novel with the same plot, written by thousands of different authors. Clark discusses the assassination at length, noting that one of the hospital's Confederate patients did not share in the sorrow: "One Johnny who expressed his pleasure at the President's death would have been strung up in double-quick time had he not been rescued by the guards and taken to the Provost Marshall's."

More diary details available upon request. With--11 related hospital administration documents addressed to Clark or the supervising surgeon William Lyman Faxon, including a letter describing the status of three patients who underwent secondary amputations; an official order on embalming services; an order to prepare for an influx of new patients from Petersburg; and a schedule for the auction of "the effects of deceased soldiers, consisting of clothing, watches, and other valuables," 24 March 1865.

Exhibition Hours

Exhibition Hours

Aliquam vulputate ornare congue. Vestibulum maximus, libero in placerat faucibus, risus nisl molestie massa, ut maximus metus lectus vel lorem.