Sale 2687 - Lot 96

Unsold

Estimate: $ 4,000 - $ 6,000

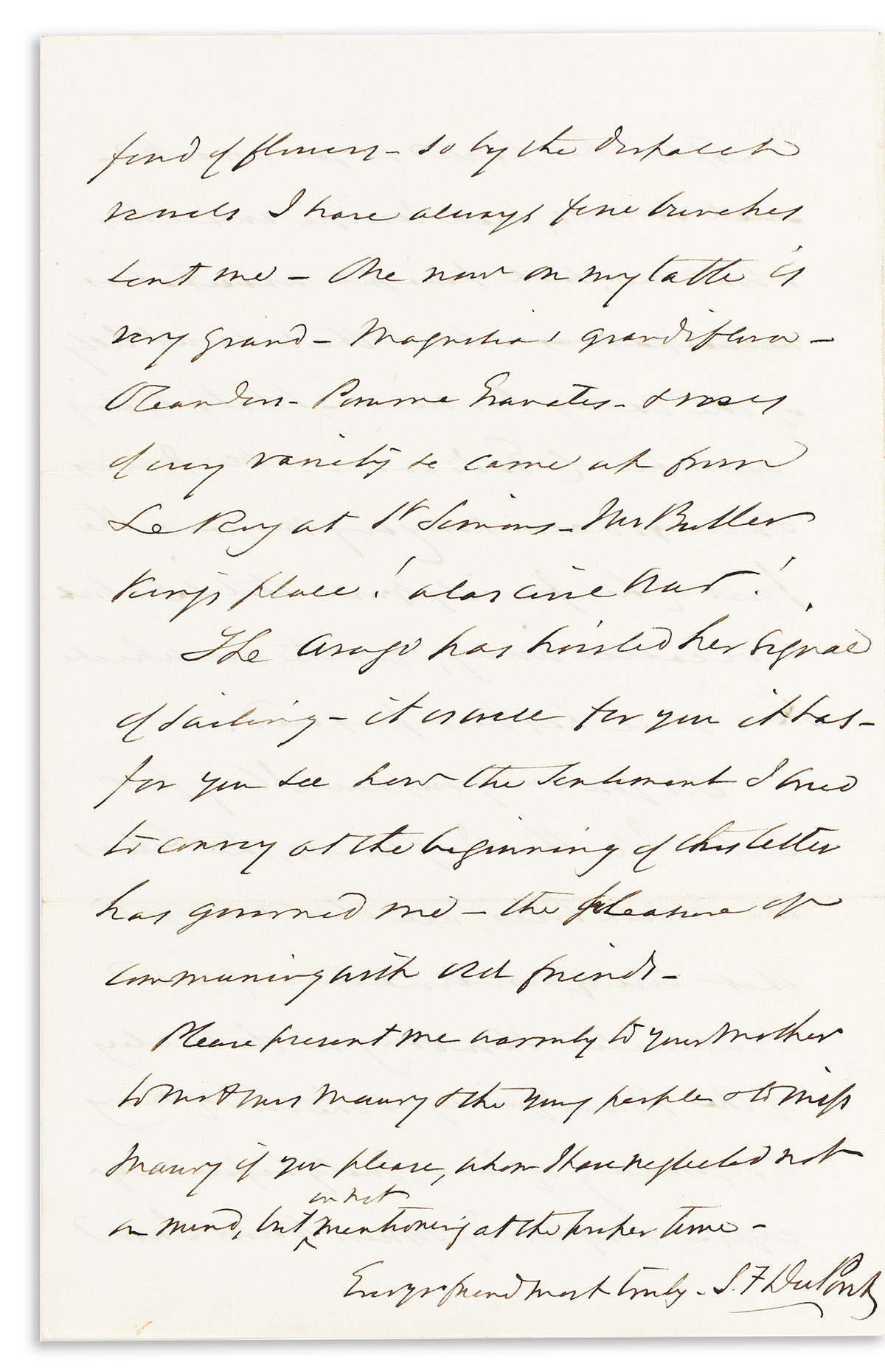

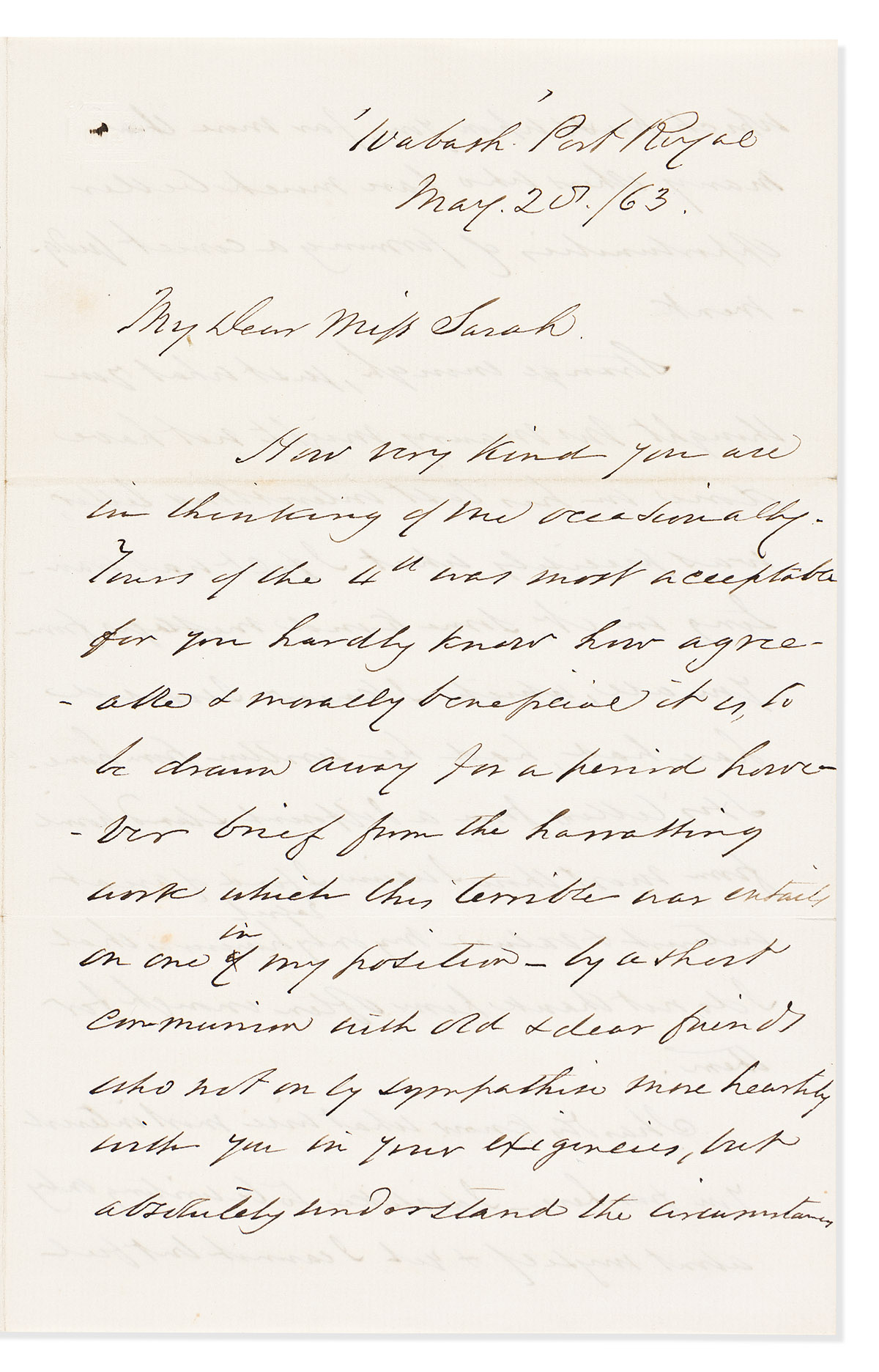

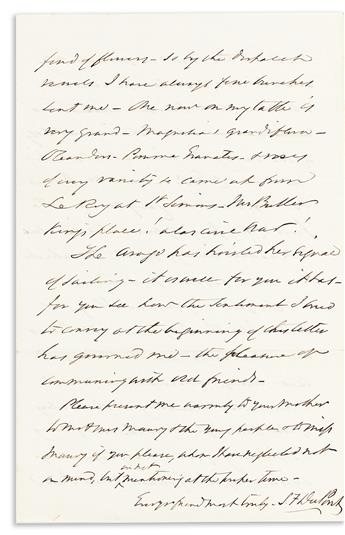

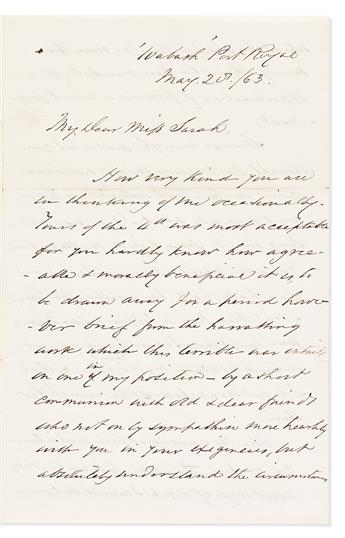

(CIVIL WAR--NAVY.) Samuel F. Du Pont. Pair of letters by the admiral concerning the doomed effort to capture Charleston by sea. Autograph Letters Signed as "S F Du Pont" to friend Sarah Gilpin. 12, 16 pages, 8 x 5 inches, on 7 folding sheets; minimal wear. With two later envelopes. Aboard the U.S.S. Wabash off Port Royal, SC, 20 January and 20 May 1863

Additional Details

The letters are addressed to Sarah Lydia Gilpin (1802-1894) of New York, an old friend of Du Pont's wife Sophie. At this time, Du Pont was heading a blockading fleet based out of the Union stronghold at Port Royal, SC.

The first letter is dated 20 January 1863. Regarding his recent promotion to Rear Admiral, he rued: "There is blood & carnage over the land. The nucleus of a decent army would have garrisoned our forts, half a nucleus of a decent navy would have supplied them, and the rebellion would have been crushed as easily as Mr. Calhoun was put down." He also reflects on his own naval career: "It has always been a satisfaction to me that I had no part in choosing my profession. I was so young that my parents decided for me." The fleet welcomed the arrival of a new class of warships for the long-planned campaign to take the fortified port of Charleston: "The ironclads are in on me, & betoken work. I hope all will be sent that are ready. Twenty long months of labor with scientific direction have been expended on Charleston. . . . The Br[itish] officers who go in & out smile at its being taken, & say it is stronger than Sebastopol. It looks like a Balaclava charge of cavalry, but God will cover our heads perhaps. . . . The army can give us scarcely any assistance." In the meantime, the blockade continues: "We took a schooner with 99 bales of cotton yesterday off Charleston, & the Huntress, now Tropic, steamer, was burnt with 360 bales."

The second letter was written on 20 May, in the wake of Du Pont's failed assault in the 7 April Battle of Charleston Harbor. His fleet of ironclads had proved to be a disappointment and barely threatened the harbor defenses. "My position at this moment with the Navy Dept is officially most critical. . . . I have received two communications which are far from pleasant. . . . I did not call a failure a reconnaissance. I told them to renew the attack would be to convert failure into disaster. I told them, moreover, that Charleston could not be taken by a purely naval attack." He suspects that the goal is to "set me aside to prosecute more freely the Monitor insanity. . . . The President is very friendly to me, & also Mr. Welles, the Sec'y, but poor man, he is not the Sec'y." On a happier note, he reflects on the beauty of the blooming dogwoods and lilacs, and adds that "my com'd'g officers know I am fond of flowers, so by the dispatch vessels I have always fine bunches sent me." After signing off, he adds a fourth leaf with a postscript, reflecting on the intelligence and refinement of the captains serving under him. He concludes by answering a question which many had been asking: "There is no probability of any second attack on Charleston. No order to this effect has been given & I think no second folly will be attempted. . . . . They had a certain dread of the Monitors before, they would laugh at us now."

Du Pont's reading of the winds was accurate. After taking the blame for the doomed assault, he was recalled from his post soon after writing this letter, bringing his otherwise distinguished career at sea to a close. Charleston did not fall until General Sherman's army took it by land.

Provenance: Gilpin family papers (see lot 129).

The first letter is dated 20 January 1863. Regarding his recent promotion to Rear Admiral, he rued: "There is blood & carnage over the land. The nucleus of a decent army would have garrisoned our forts, half a nucleus of a decent navy would have supplied them, and the rebellion would have been crushed as easily as Mr. Calhoun was put down." He also reflects on his own naval career: "It has always been a satisfaction to me that I had no part in choosing my profession. I was so young that my parents decided for me." The fleet welcomed the arrival of a new class of warships for the long-planned campaign to take the fortified port of Charleston: "The ironclads are in on me, & betoken work. I hope all will be sent that are ready. Twenty long months of labor with scientific direction have been expended on Charleston. . . . The Br[itish] officers who go in & out smile at its being taken, & say it is stronger than Sebastopol. It looks like a Balaclava charge of cavalry, but God will cover our heads perhaps. . . . The army can give us scarcely any assistance." In the meantime, the blockade continues: "We took a schooner with 99 bales of cotton yesterday off Charleston, & the Huntress, now Tropic, steamer, was burnt with 360 bales."

The second letter was written on 20 May, in the wake of Du Pont's failed assault in the 7 April Battle of Charleston Harbor. His fleet of ironclads had proved to be a disappointment and barely threatened the harbor defenses. "My position at this moment with the Navy Dept is officially most critical. . . . I have received two communications which are far from pleasant. . . . I did not call a failure a reconnaissance. I told them to renew the attack would be to convert failure into disaster. I told them, moreover, that Charleston could not be taken by a purely naval attack." He suspects that the goal is to "set me aside to prosecute more freely the Monitor insanity. . . . The President is very friendly to me, & also Mr. Welles, the Sec'y, but poor man, he is not the Sec'y." On a happier note, he reflects on the beauty of the blooming dogwoods and lilacs, and adds that "my com'd'g officers know I am fond of flowers, so by the dispatch vessels I have always fine bunches sent me." After signing off, he adds a fourth leaf with a postscript, reflecting on the intelligence and refinement of the captains serving under him. He concludes by answering a question which many had been asking: "There is no probability of any second attack on Charleston. No order to this effect has been given & I think no second folly will be attempted. . . . . They had a certain dread of the Monitors before, they would laugh at us now."

Du Pont's reading of the winds was accurate. After taking the blame for the doomed assault, he was recalled from his post soon after writing this letter, bringing his otherwise distinguished career at sea to a close. Charleston did not fall until General Sherman's army took it by land.

Provenance: Gilpin family papers (see lot 129).

Exhibition Hours

Exhibition Hours

Aliquam vulputate ornare congue. Vestibulum maximus, libero in placerat faucibus, risus nisl molestie massa, ut maximus metus lectus vel lorem.