Sale 2505 - Lot 65

Price Realized: $ 7,500

Price Realized: $ 9,375

?Final Price Realized includes Buyer’s Premium added to Hammer Price

Estimate: $ 5,000 - $ 7,500

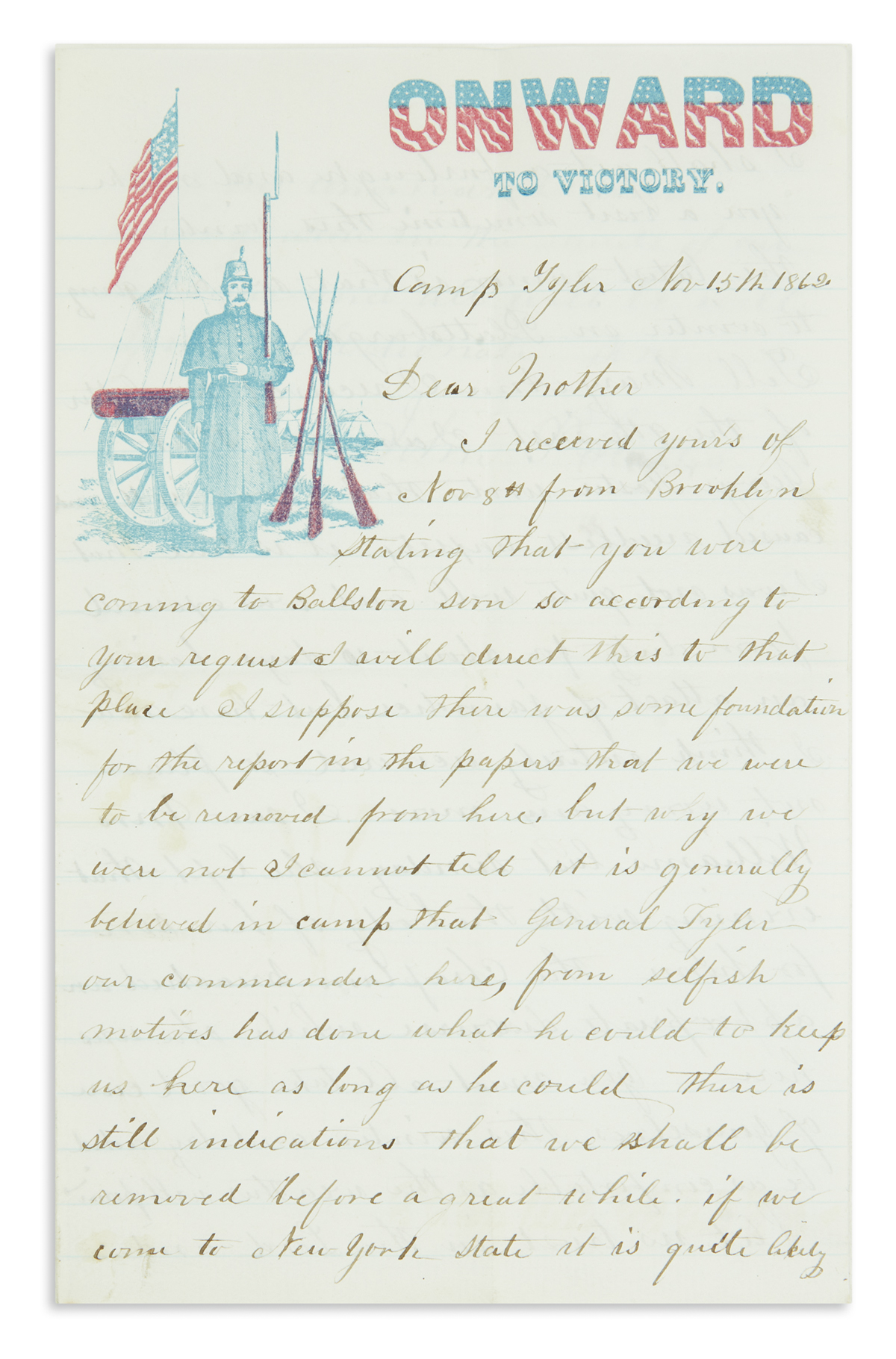

(CIVIL WAR--NEW YORK.) Staples, John P. Large archive of letters describing the Battle of Fort Fisher and more. 101 Autograph Letters Signed written during his Civil War service; condition generally strong with tape repairs to a few letters. Vp, August 1862 to April 1865

Additional Details

An extensive archive of nearly one hundred letters written by Corporal John P. Staples (1833-1918) of the 115th New York Infantry to his mother, sister, and brother back home in Saratoga County, NY. The letters are well-written, legible, and highly literate, relating in very readable fashion the movements of his regiment, news of the local men, his great faith in God, and his general impressions of the war.

The New York 115th Infantry was a three-year regiment recruited in summer 1862. The regiment was soon captured at Harper's Ferry, as described in his 17 September 1862 letter: "We were obliged to surrender for want of ammunition and probably a sufficient force to hold the place. . . . We were bombarded from all sides." They were paroled to Chicago to await prisoner exchange. After parole, the unit served in Hilton Head and Beaufort, SC, from where he reported on the aftermath of Fort Wagner on 28 July 1863: "Quite a large part of the wounded sent here . . . were colored from the 54th Mass. It is said they fought extraordinarily well in the late fights up there. . . . There is not as much prejudice and hatred toward the negro race among the soldiers as formerly; it is singular that the brutal cowards of New York should without any cause vent their spite in such horrible barbarities on the black women and children." The regiment spent February and March 1864 in Florida, then went on to Virginia. On 17 June 1864, Staples offers an interesting report: "I was talking with one of the darkey soldiers. . . . He was in the fight near Petersburg the day before when they captured three lines of rebel entrenchments. They also charged a fort near the town, capturing it with sixteen heavy guns. He said they took no prisoners, that when they entered the fort the rebels cried for quarter, but remembering the massacre at Fort Pillow and the treatment they would expect to receive under similar circumstances, they bayoneted all that could not get away, at the same time saying 'Give them Fort Pillow.'" He also reports on the Battle of the Crater on 1 August 1864, which began "by our blowing up one of the rebel forts and immediately charging their works. The fort was completely destroyed, burying the men and cannon in one promiscuous heap. . . . Though we were more than a half a mile away, it shook the ground like an earthquake."

The most dramatic of the letters is an eyewitness account of the Battle of Fort Fisher dated 27 January 1865: "We charged on past those that were before us, the rebels gradually retiring before us from one bombproof to another. . . . About 9 o'clock, we began moving forward and found the rebels huddled in their bombproofs ready to surrender to the victorious Yankees, though it is said that some of them through the effects of liquor were foolish enough to fire on our troops after they were fairly captured and some of the men were obliged to fire into the bombproofs before they would be quiet." Staples also gives an account of the explosion of the magazine, which killed a number of Union soldiers after they had captured the fort: "It seems impossible to tell at present whether it was done by rebels' infernal machinery, or the carelessness of our own men. I am inclined to think now that it was the latter, though the rebs are none too good for such cowardly act. Luckily, or perhaps I should say providentially, I was a little distance from where the regiment was lying at the time of the blowup. . . . There was a tremendous shock, and I was enveloped in midnight darkness surrounded with falling masses of timbers, dirt and rubbish, expecting though nearly stunned every moment to be crushed or buried beneath the debris which it seemed to me would never cease to fall, but the bank of earth above mentioned protected me from the force of the explosion and I was preserved to assist my more unfortunate companions." A 4 March 1865 letter describes the harrowing sight of starving and abused prisoners freed from Confederate custody.

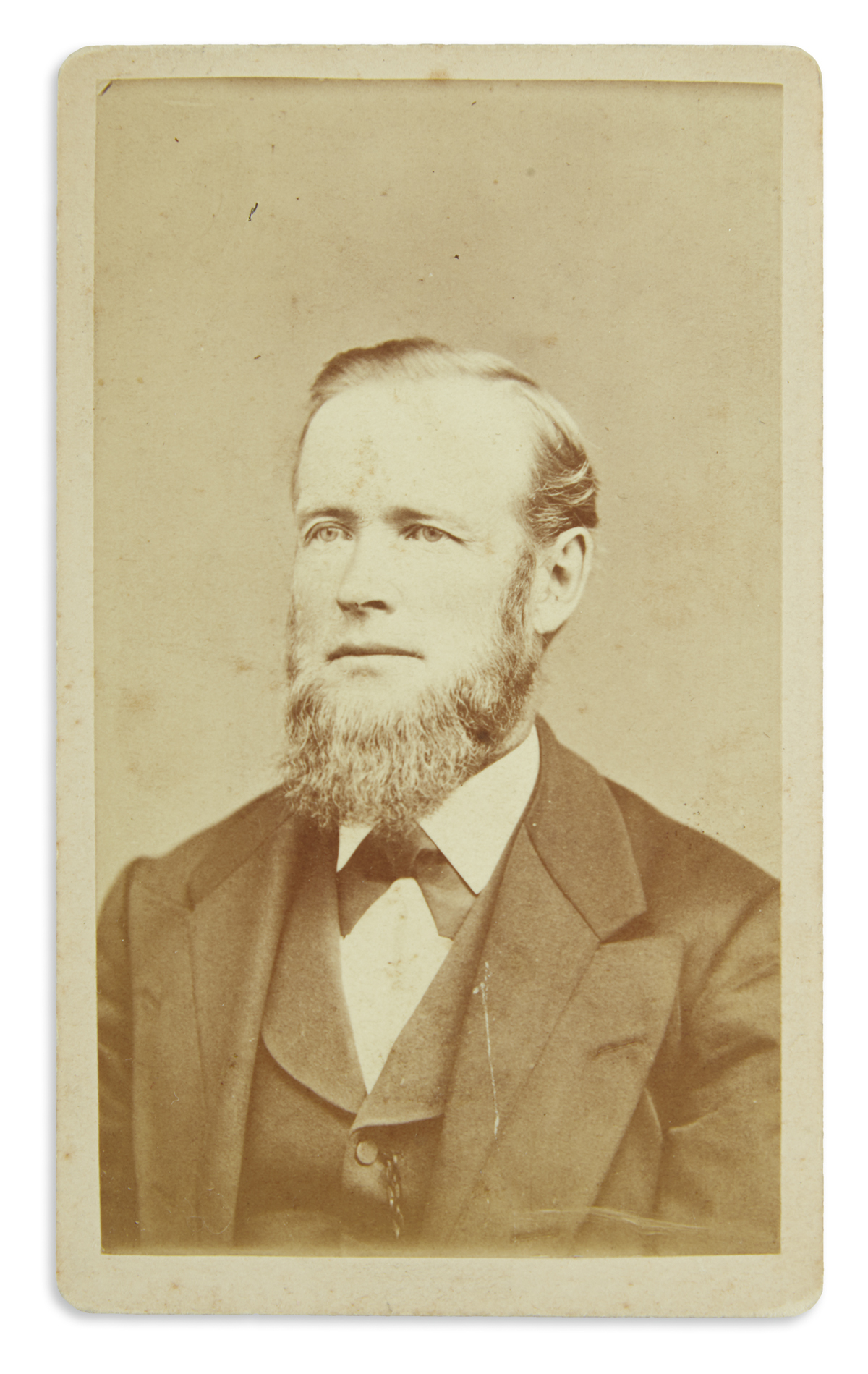

Staples survived the war and settled in California by the 1880s; one final letter is dated 1902 and discusses an engraving of the Battle of Fort Fisher. Staples died from asphyxiation caused by a gas leak in his apartment at the age of 85. This remarkable archive is a fitting testament to his service. with--5 other family letters dated 1857 to 1902, a cased image, 2 cartes-de-visite of Staples, a later portrait, and a reunion photograph of him and several men from his regiment.

The New York 115th Infantry was a three-year regiment recruited in summer 1862. The regiment was soon captured at Harper's Ferry, as described in his 17 September 1862 letter: "We were obliged to surrender for want of ammunition and probably a sufficient force to hold the place. . . . We were bombarded from all sides." They were paroled to Chicago to await prisoner exchange. After parole, the unit served in Hilton Head and Beaufort, SC, from where he reported on the aftermath of Fort Wagner on 28 July 1863: "Quite a large part of the wounded sent here . . . were colored from the 54th Mass. It is said they fought extraordinarily well in the late fights up there. . . . There is not as much prejudice and hatred toward the negro race among the soldiers as formerly; it is singular that the brutal cowards of New York should without any cause vent their spite in such horrible barbarities on the black women and children." The regiment spent February and March 1864 in Florida, then went on to Virginia. On 17 June 1864, Staples offers an interesting report: "I was talking with one of the darkey soldiers. . . . He was in the fight near Petersburg the day before when they captured three lines of rebel entrenchments. They also charged a fort near the town, capturing it with sixteen heavy guns. He said they took no prisoners, that when they entered the fort the rebels cried for quarter, but remembering the massacre at Fort Pillow and the treatment they would expect to receive under similar circumstances, they bayoneted all that could not get away, at the same time saying 'Give them Fort Pillow.'" He also reports on the Battle of the Crater on 1 August 1864, which began "by our blowing up one of the rebel forts and immediately charging their works. The fort was completely destroyed, burying the men and cannon in one promiscuous heap. . . . Though we were more than a half a mile away, it shook the ground like an earthquake."

The most dramatic of the letters is an eyewitness account of the Battle of Fort Fisher dated 27 January 1865: "We charged on past those that were before us, the rebels gradually retiring before us from one bombproof to another. . . . About 9 o'clock, we began moving forward and found the rebels huddled in their bombproofs ready to surrender to the victorious Yankees, though it is said that some of them through the effects of liquor were foolish enough to fire on our troops after they were fairly captured and some of the men were obliged to fire into the bombproofs before they would be quiet." Staples also gives an account of the explosion of the magazine, which killed a number of Union soldiers after they had captured the fort: "It seems impossible to tell at present whether it was done by rebels' infernal machinery, or the carelessness of our own men. I am inclined to think now that it was the latter, though the rebs are none too good for such cowardly act. Luckily, or perhaps I should say providentially, I was a little distance from where the regiment was lying at the time of the blowup. . . . There was a tremendous shock, and I was enveloped in midnight darkness surrounded with falling masses of timbers, dirt and rubbish, expecting though nearly stunned every moment to be crushed or buried beneath the debris which it seemed to me would never cease to fall, but the bank of earth above mentioned protected me from the force of the explosion and I was preserved to assist my more unfortunate companions." A 4 March 1865 letter describes the harrowing sight of starving and abused prisoners freed from Confederate custody.

Staples survived the war and settled in California by the 1880s; one final letter is dated 1902 and discusses an engraving of the Battle of Fort Fisher. Staples died from asphyxiation caused by a gas leak in his apartment at the age of 85. This remarkable archive is a fitting testament to his service. with--5 other family letters dated 1857 to 1902, a cased image, 2 cartes-de-visite of Staples, a later portrait, and a reunion photograph of him and several men from his regiment.

Exhibition Hours

Exhibition Hours

Aliquam vulputate ornare congue. Vestibulum maximus, libero in placerat faucibus, risus nisl molestie massa, ut maximus metus lectus vel lorem.