Sale 2580 - Lot 115

Price Realized: $ 425

Price Realized: $ 531

?Final Price Realized includes Buyer’s Premium added to Hammer Price

Estimate: $ 800 - $ 1,200

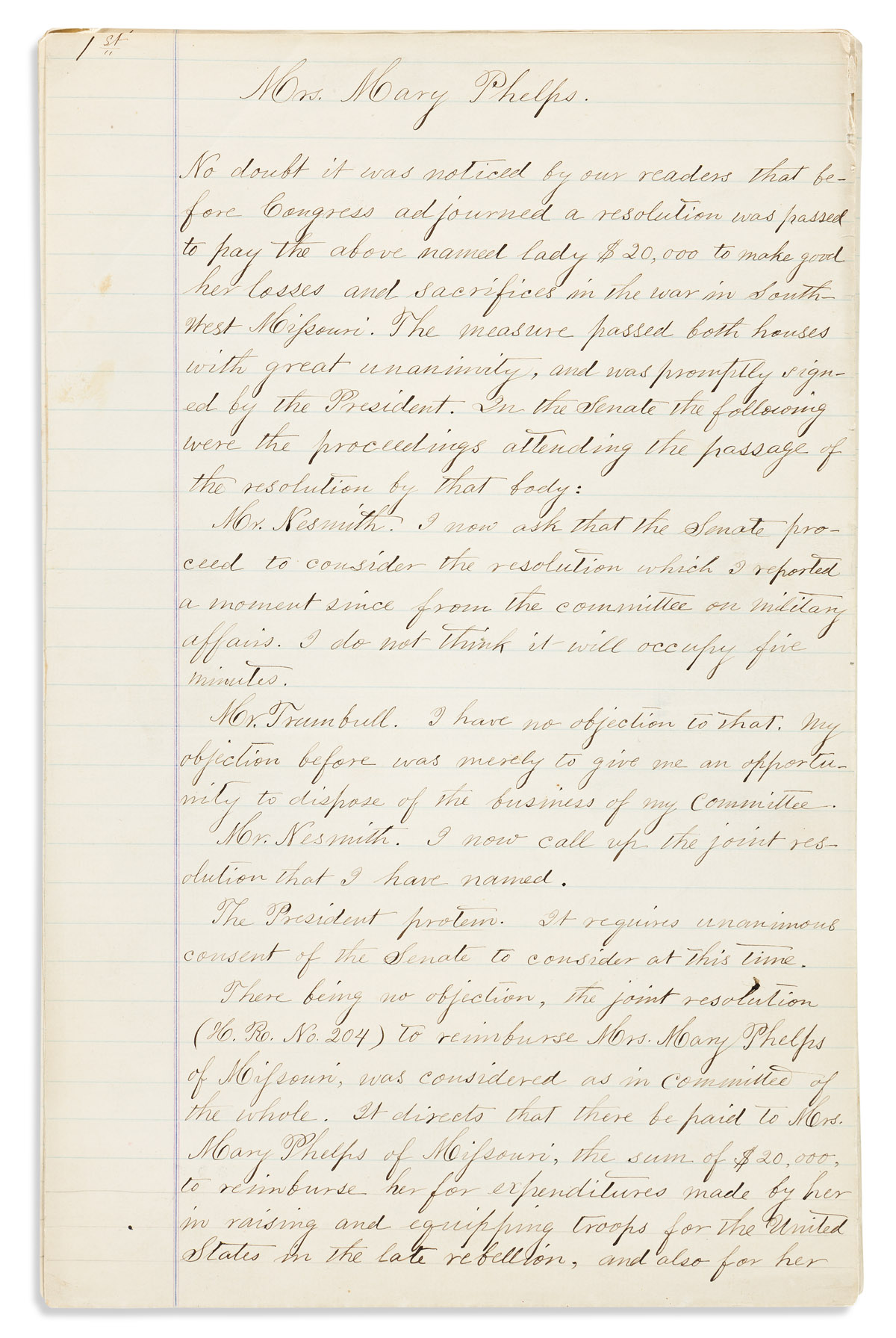

(CIVIL WAR--WOMEN.) Mary Whitney Phelps. Partial memoir by the celebrated civilian hero of Missouri. 1-9, 13-26 leaves of an ink manuscript fair copy with pencil edits, 25 x 8 inches, each folded horizontally and blank on verso, followed by an additional worn smaller leaf of an earlier pencil draft numbered 27 and 28; apparently lacking leaves 10, 11, and 12, otherwise minor wear. No place, late 19th century

Additional Details

Mary Whitney Phelps (1812-1878) was one of Missouri's Union heroes of the Civil War. Her husband John Smith Phelps (1814-1886) of Springfield, MO represented Missouri in the United States Congress, but returned home to fight for the Union at the outbreak of the rebellion. The 10 August 1861 Battle of Wilson's Creek, the first major battle west of the Mississippi, was a defeat for the Union and resulted in the death of Union commander Nathaniel Lyon. The Confederates under General Sterling Price soon occupied Springfield. Rather than flee with other prominent Unionists, Mrs. Phelps remained behind in Springfield to see to the burial of the fallen General Lyon, and to care for wounded soldiers who had been left behind during the retreat. The Missouri chapter of the Daughters of Union Veterans is named in her honor; she was also the subject of a 2008 biography, Jerena East Giffen's "Mary, Mary Quite . . . The Life and Times of Mary Whitney Phelps."

This apparently unpublished manuscript memoir begins with an extract from the Congressional Globe of 27 July 1866 (pages 4227-8) in which she was granted $20,000 as reimbursement for her services, followed by her preface explaining that "the object of this work is to correct some mistaken ideas which have been published to the world in newspapers regarding this appropriation, why it was made, and how expended."

The manuscript is missing three leaves, including any discussion of the Battle of Wilson's Creek, but resumes on leaf 13 with her discussion of the burial of General Lyon. With the Confederate army expected in town in six hours, she hunted down the town's only remaining coffinmaker, an old man who had retired from business for lack of assistants, and was terrified of angering the Confederates. She selected the wood, gave him a four-hour deadline, "then I went home to have a grave dug. I set my gardener, an Irishman, and a Negro man to work at it," and returned to town to watch over the body, embalming it herself with bay rum. A 3 p.m. "the rebels began to pour into town, yelping like wild Indians. The yard and house were filled in an hour, so that it was impossible to move about. I took my stand by the dead body. . . . Some were chasing the fowls, others were in the garden pulling up vegetables, and others stripping the peach and apple trees." A rebel commander brought them to order with a pistol shot, explaining with a laugh "that is the only way I can make them d___d rascals obey my orders." The coffin was completed, but the grave had not been dug--two more days passed before she laid the general to rest.

The Confederate General Price then sent an aide (actual name Major J.T. Major) to clear the encamped rebels from her home, and brought her to a church where the Union wounded had been warehoused: "Oh, the horrible sight! They were thrown upon the bare floor almost in piles; some dead, others dying, and some in a state of nudity" (leaf 18)--much their clothing had been confiscated by ill-clad rebel troops. Mrs. Phelps and a handful of other local Union women assumed responsibility for the surviving wounded: "Five days after the battle, I removed to my house thirty wounded soldiers, all privates, and very badly wounded. The officers generally had money, and could find those who would nurse them for pay, but the poor privates had neither money, nor a change of clothes." With the help of her enslaved servants, she had them all bathed, and fed them bread, milk, and peaches. Her servant George was captured and imprisoned by the rebels, with plans to send him south, but she went to the rebel camp to rescue him (back into servitude), a story told at great length, closing her narrative.

The narrative was composed in the first person by Mary Whitney Phelps. We have been unable to find comparisons for the handwriting. The earlier fragments of the pencil draft could plausibly date from the lifetime of Mrs. Phelps (who died in 1878) and are quite possibly in her hand. The ink fair copy is in a different hand and looks somewhat later.

WITH--4 additional leaves of the original pencil draft of the memoir, most of which correlate to selections in the ink fair copy

Autograph Letter Signed from John Smith Phelps to his daughter Mary in New York, mostly about lack of money and the progress of crops: "Every thing is moving along in its own time here, save now & then a party of Bushwhackers pass thru the country." Springfield, MO, 19 May 1865

Typescript copy of a letter by daughter Mary Ann Phelps Montgomery to Ben Lammers of Springfield, MO, discussing the monument to John Smith Phelps in Springfield. Portland, OR, 21 December 1936

Two typescript pages from a memoir by daughter Mary Ann Phelps Montgomery about her life in Portland, OR in the 1870s.

55-point response in pencil to an unknown questionnaire regarding the war years.

This apparently unpublished manuscript memoir begins with an extract from the Congressional Globe of 27 July 1866 (pages 4227-8) in which she was granted $20,000 as reimbursement for her services, followed by her preface explaining that "the object of this work is to correct some mistaken ideas which have been published to the world in newspapers regarding this appropriation, why it was made, and how expended."

The manuscript is missing three leaves, including any discussion of the Battle of Wilson's Creek, but resumes on leaf 13 with her discussion of the burial of General Lyon. With the Confederate army expected in town in six hours, she hunted down the town's only remaining coffinmaker, an old man who had retired from business for lack of assistants, and was terrified of angering the Confederates. She selected the wood, gave him a four-hour deadline, "then I went home to have a grave dug. I set my gardener, an Irishman, and a Negro man to work at it," and returned to town to watch over the body, embalming it herself with bay rum. A 3 p.m. "the rebels began to pour into town, yelping like wild Indians. The yard and house were filled in an hour, so that it was impossible to move about. I took my stand by the dead body. . . . Some were chasing the fowls, others were in the garden pulling up vegetables, and others stripping the peach and apple trees." A rebel commander brought them to order with a pistol shot, explaining with a laugh "that is the only way I can make them d___d rascals obey my orders." The coffin was completed, but the grave had not been dug--two more days passed before she laid the general to rest.

The Confederate General Price then sent an aide (actual name Major J.T. Major) to clear the encamped rebels from her home, and brought her to a church where the Union wounded had been warehoused: "Oh, the horrible sight! They were thrown upon the bare floor almost in piles; some dead, others dying, and some in a state of nudity" (leaf 18)--much their clothing had been confiscated by ill-clad rebel troops. Mrs. Phelps and a handful of other local Union women assumed responsibility for the surviving wounded: "Five days after the battle, I removed to my house thirty wounded soldiers, all privates, and very badly wounded. The officers generally had money, and could find those who would nurse them for pay, but the poor privates had neither money, nor a change of clothes." With the help of her enslaved servants, she had them all bathed, and fed them bread, milk, and peaches. Her servant George was captured and imprisoned by the rebels, with plans to send him south, but she went to the rebel camp to rescue him (back into servitude), a story told at great length, closing her narrative.

The narrative was composed in the first person by Mary Whitney Phelps. We have been unable to find comparisons for the handwriting. The earlier fragments of the pencil draft could plausibly date from the lifetime of Mrs. Phelps (who died in 1878) and are quite possibly in her hand. The ink fair copy is in a different hand and looks somewhat later.

WITH--4 additional leaves of the original pencil draft of the memoir, most of which correlate to selections in the ink fair copy

Autograph Letter Signed from John Smith Phelps to his daughter Mary in New York, mostly about lack of money and the progress of crops: "Every thing is moving along in its own time here, save now & then a party of Bushwhackers pass thru the country." Springfield, MO, 19 May 1865

Typescript copy of a letter by daughter Mary Ann Phelps Montgomery to Ben Lammers of Springfield, MO, discussing the monument to John Smith Phelps in Springfield. Portland, OR, 21 December 1936

Two typescript pages from a memoir by daughter Mary Ann Phelps Montgomery about her life in Portland, OR in the 1870s.

55-point response in pencil to an unknown questionnaire regarding the war years.

Exhibition Hours

Exhibition Hours

Aliquam vulputate ornare congue. Vestibulum maximus, libero in placerat faucibus, risus nisl molestie massa, ut maximus metus lectus vel lorem.