Sale 2580 - Lot 126

Price Realized: $ 1,000

Price Realized: $ 1,250

?Final Price Realized includes Buyer’s Premium added to Hammer Price

Estimate: $ 1,500 - $ 2,500

DESCRIBES THE HUNGARIAN REVOLUTION FROM NEARBY ROMANIA (DIPLOMACY.) Family letters of Ambassador Robert H. Thayer during the Cold War. Approximately 230 items (0.5 linear feet) in one box, mostly personal letters written by Ambassador Thayer and his wife to their mothers; condition generally strong, many of the letters in original stamped and postmarked envelopes, condition generally strong, a bit musty, water damage to Thayer's personnel file only. Various places, bulk 1950-59

Additional Details

Robert Helyer Thayer (1901-1984) graduated from Amherst College and Harvard Law, and embarked on a wide-ranging career which intersected with the Lindbergh kidnapping case, the D-Day landings at Normandy, and the founding of the United Nations. This archive of family correspondence dates from his diplomatic career as Assistant Ambassador to France, 1950-1954 and as Ambassador to Romania, 1955-1957. During his time in Romania, the Soviet Union used Romania as its entry point for crushing the Hungarian Revolution in October-November 1956.

From the period when Thayer served as Assistant Ambassador to France, 1950-54, are approximately 66 letters to his mother Violet Otis Thayer (1871-1962) in Boston. This was the final period of both American economic support for France via the Marshall Plan, and for the French battle against Vietnamese independence.

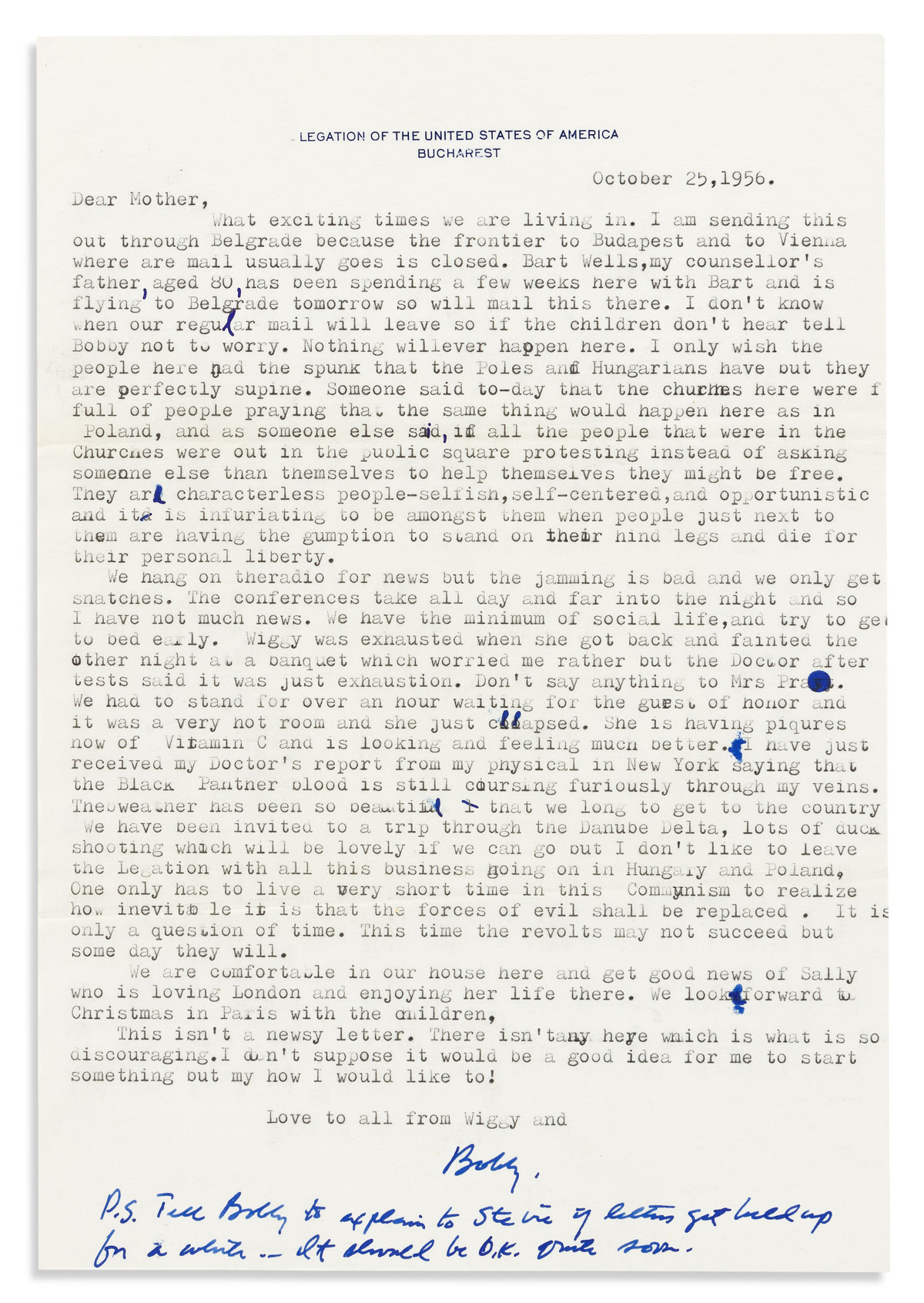

Thayer's time as Ambassador to Romania has even more documentation, including approximately 55 letters to his mother. His 25 October 1956 letter was written just two days after the start of massive student demonstrations in neighboring Hungary--a momentous development for a committed Cold Warrior like Thayer, although he was disappointed that the Romanians did not follow their lead: "What exciting times we are living in. . . . I only wish the people here had the spunk that the Poles and Hungarians have but they are perfectly supine. Someone said today that the churches here were full of people praying that the same thing would happen here as in Poland. . . . If all the people that were in the churches were out in the public squares protesting instead of asking someone else than themselves to help they might be free. . . . It is infuriating to be amongst them when people just next to them are having the gumption to stand on their hind legs and die for their personal liberty. . . . One only has to live a very short time in this Communism to realize how inevitable it is that the forces of evil shall be replaced."

On 6 November after the Hungarian revolt had been crushed, he wrote "Here we are so heartbroken over Hungary that it is terrible. The stories of the bravery and willingness to die of those boys is wonderful and a proof that Communism can never last. . . . People can't help being sure that Communism is dying the natural death that everyone knew it would. . . . There are signs of decay that are very exciting. Tomorrow is the Soviet holiday but nobody is going near them. They can celebrate all by themselves and drink themselves into sodden despair for all I care."

His 13 November letter offered more details after communicating with the locked-down American legation in Hungary. He described the movement of Soviet troops through Romania and saw that his efforts to draw the Romanian government slowly toward capitalism was for naught: "They have to be taught that to deal with us they have to keep their hands clean and get away from the Soviets." He proudly describes snubbing the Soviet ambassador at the airport: "He looked very embarrassed since this was in front of a great many people and I may say that I enjoyed his discomfiture." On 29 November he described dining with the long-serving Romanian Communist leader Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej, "the Khrushchev of Rumania, and had the pleasure of telling him what the American people thought of the Soviet actions in Hungary."

Also from Romania are 45 letters from the ambassador's wife Virginia Pratt Thayer (1905-1979) to her own mother Ruth Baker Pratt (1877-1965), who had served in the United States Congress in the 1930s. These letters are filled with diplomatic gossip. Her 28 November [1956] letter shares a slice of Iron Curtain life: "While walking the dogs I was accosted by a charming older lady who stayed with me during the entire walk. She was . . . a most agreeable companion, but we are being beset these days by provocatures, in an effort to get charges against one of us, and I could not relax in her company. . . . That is the vile side of the Soviet orbit. The eternal atmosphere of suspicion of one's neighbor finally infects even us, the free and open characters." Her 4 November 1957 letter describes the suspicious death of Romania's foreign minister Grigore Preoteasa (1915-1957) in an airplane crash. Her letters are all accompanied by full typed transcripts. Virginia Thayer also wrote a 32-page typescript memoir of her arrival and early days in Bucharest which is included.

Also of interest is a carbon copy of a 1973 interview Thayer did with Columbia University on his time with the Eisenhower administration, with some related permissions correspondence through 1983.

Rounding out the collection are an English-Romanian phrase book, Thayer's diplomatic personnel file from circa 1959 through his 1964 retirement, and more. This archive offers a deeply personal look into diplomatic life behind the Iron Curtain during the Cold War.

From the period when Thayer served as Assistant Ambassador to France, 1950-54, are approximately 66 letters to his mother Violet Otis Thayer (1871-1962) in Boston. This was the final period of both American economic support for France via the Marshall Plan, and for the French battle against Vietnamese independence.

Thayer's time as Ambassador to Romania has even more documentation, including approximately 55 letters to his mother. His 25 October 1956 letter was written just two days after the start of massive student demonstrations in neighboring Hungary--a momentous development for a committed Cold Warrior like Thayer, although he was disappointed that the Romanians did not follow their lead: "What exciting times we are living in. . . . I only wish the people here had the spunk that the Poles and Hungarians have but they are perfectly supine. Someone said today that the churches here were full of people praying that the same thing would happen here as in Poland. . . . If all the people that were in the churches were out in the public squares protesting instead of asking someone else than themselves to help they might be free. . . . It is infuriating to be amongst them when people just next to them are having the gumption to stand on their hind legs and die for their personal liberty. . . . One only has to live a very short time in this Communism to realize how inevitable it is that the forces of evil shall be replaced."

On 6 November after the Hungarian revolt had been crushed, he wrote "Here we are so heartbroken over Hungary that it is terrible. The stories of the bravery and willingness to die of those boys is wonderful and a proof that Communism can never last. . . . People can't help being sure that Communism is dying the natural death that everyone knew it would. . . . There are signs of decay that are very exciting. Tomorrow is the Soviet holiday but nobody is going near them. They can celebrate all by themselves and drink themselves into sodden despair for all I care."

His 13 November letter offered more details after communicating with the locked-down American legation in Hungary. He described the movement of Soviet troops through Romania and saw that his efforts to draw the Romanian government slowly toward capitalism was for naught: "They have to be taught that to deal with us they have to keep their hands clean and get away from the Soviets." He proudly describes snubbing the Soviet ambassador at the airport: "He looked very embarrassed since this was in front of a great many people and I may say that I enjoyed his discomfiture." On 29 November he described dining with the long-serving Romanian Communist leader Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej, "the Khrushchev of Rumania, and had the pleasure of telling him what the American people thought of the Soviet actions in Hungary."

Also from Romania are 45 letters from the ambassador's wife Virginia Pratt Thayer (1905-1979) to her own mother Ruth Baker Pratt (1877-1965), who had served in the United States Congress in the 1930s. These letters are filled with diplomatic gossip. Her 28 November [1956] letter shares a slice of Iron Curtain life: "While walking the dogs I was accosted by a charming older lady who stayed with me during the entire walk. She was . . . a most agreeable companion, but we are being beset these days by provocatures, in an effort to get charges against one of us, and I could not relax in her company. . . . That is the vile side of the Soviet orbit. The eternal atmosphere of suspicion of one's neighbor finally infects even us, the free and open characters." Her 4 November 1957 letter describes the suspicious death of Romania's foreign minister Grigore Preoteasa (1915-1957) in an airplane crash. Her letters are all accompanied by full typed transcripts. Virginia Thayer also wrote a 32-page typescript memoir of her arrival and early days in Bucharest which is included.

Also of interest is a carbon copy of a 1973 interview Thayer did with Columbia University on his time with the Eisenhower administration, with some related permissions correspondence through 1983.

Rounding out the collection are an English-Romanian phrase book, Thayer's diplomatic personnel file from circa 1959 through his 1964 retirement, and more. This archive offers a deeply personal look into diplomatic life behind the Iron Curtain during the Cold War.

Exhibition Hours

Exhibition Hours

Aliquam vulputate ornare congue. Vestibulum maximus, libero in placerat faucibus, risus nisl molestie massa, ut maximus metus lectus vel lorem.