Sale 2687 - Lot 133

Price Realized: $ 1,500

Price Realized: $ 1,875

?Final Price Realized includes Buyer’s Premium added to Hammer Price

Estimate: $ 3,000 - $ 4,000

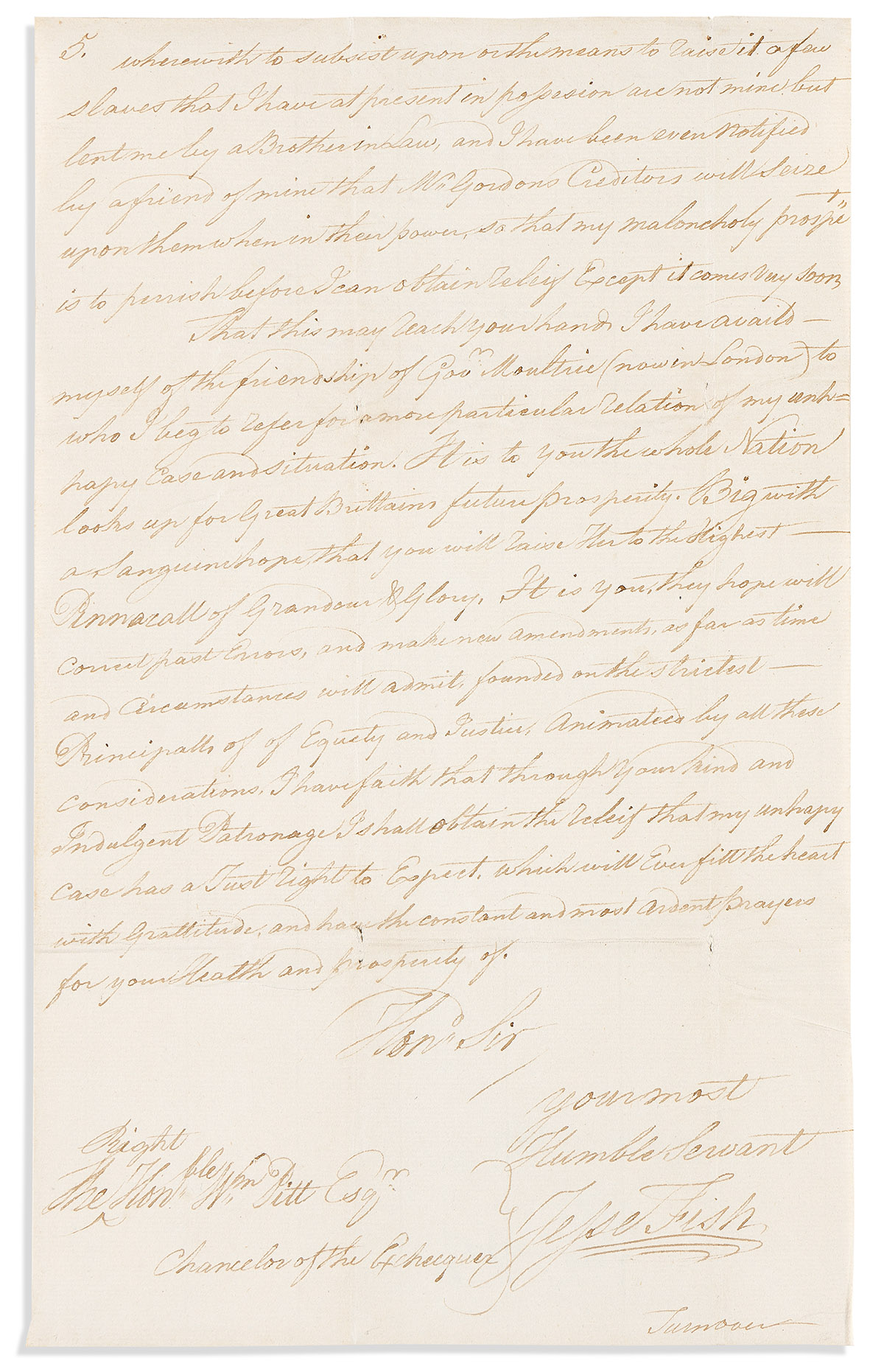

(FLORIDA.) Jesse Fish. The notorious early Florida land speculator shares his life story with the British Prime Minister. Autograph Letter Signed to William Pitt, Prime Minister and Chancellor of the Exchequer of Great Britain. 6 pages, 12¾ x 7¾ inches, on 2 sheets, including postscript and docketing on final page (no address panel or postal markings); mailing folds, minimal wear. With typed transcript. Saint Augustine, FL, 15 April 1787

Additional Details

Jesse Fish (circa 1725-1790) built a great fortune while straddling two colonial masters, earning the suspicion of both sides. This letter tells his life story--or at least his version of it, a version calculated to garner sympathy.

Born in colonial New York, young Fish was sent as an apprentice to Spanish St. Augustine, Florida. When English merchants were expelled in 1738, he became the only Englishman in the city, and established himself as an important mercantile connection to the English world. When the Spanish ceded Florida to England in 1763, Fish remained there as a prosperous merchant. He acted as land agent for many of the departed Spanish colonists, and ended up with control over nearly half of the city's real estate. When Spanish regained control in 1783, and all other English evacuated, Fish once again remained the city's one constant. He owned the massive Anastasia Island, where his plantation was famous for its oranges; he owned 17 slaves per 1787 tax records.

In 1787, living under Spanish rule, Fish wrote to the British prime minister in the hopes of being relocated, or getting some kind of compensation. Can't hurt to ask. Fish introduces himself as "an individual that is reduced to a very distressfull and unhappy situation; and at a period of life, aflicted with bodily infirmities, that renders him quite unfitt, and unable to encounter difficulties." He recounts the story of his life in Florida--"this unfortunate country (for me)," arriving as a boy in 1735. In the 1750s, he earned "a considerable sum of money" as a supplier to the Spanish garrison in St. Augustine, but spent most of it "to assist the needy and relieve the distressed . . . as many boath English and American vessells were frequently wrecked on the Florida coast as they were a coming through the gulph." When the Spanish were expelled in 1763, he assumed the debts of many friends rather than see them detained. By the time of the Revolution, he owned considerable real estate in the city, which "I had soon after the mortification to see torn down by the soldiers to burn . . . without being able to obtain the least satisfaction from Major James Oglivie of the 9th Reg'mt." After the war, the new British governor of Florida Grant decreed that all old British purchases of land from Spanish citizens would be null and void, further weakening his finances. An agent sent to London to negotiate for this land spent years in court and died before resolution was reached. Fish remained in Florida when the Spanish resumed control in 1783: "It may be asked how or why I have continued here after the evacuation. I answer my poverty and age, and I have a son that I earnestly wish to give as much education to as may prepare him the better to shift for himself. . . . I am here only on sufferance, as to become a Spanish subject is the last thing in life I would do. . . . I must now with the utmost regret leave it soon to undergo the last severe tryall in life on the Bahamas Islands (or rather rocks) without wherewithal to subsist upon or the means to raise it. A few slaves that I have at present in possession are not mine, but lent me by a brother-in-law. . . . My maloncholy prospect is to perrish before I can obtain relief except it comes very soon."

At this point, the Prime Minister might have taken a deep breath and asked, "Well, what do you want from me?" In conclusion, Fish expresses his faith "that through your kind and indulgent patronage I shall obtain the relief that my unhappy case has a just right to expect, which will ever fill the heart with gratitude."

This remarkable letter is apparently unpublished and unknown to scholarship. We have found no indication that Pitt responded to this entreaty, let alone granted anything to Fish. Two years later, Fish wrote another similar plea to the King of Spain, which is well-known to history. He died in St. Augustine in 1790.

Born in colonial New York, young Fish was sent as an apprentice to Spanish St. Augustine, Florida. When English merchants were expelled in 1738, he became the only Englishman in the city, and established himself as an important mercantile connection to the English world. When the Spanish ceded Florida to England in 1763, Fish remained there as a prosperous merchant. He acted as land agent for many of the departed Spanish colonists, and ended up with control over nearly half of the city's real estate. When Spanish regained control in 1783, and all other English evacuated, Fish once again remained the city's one constant. He owned the massive Anastasia Island, where his plantation was famous for its oranges; he owned 17 slaves per 1787 tax records.

In 1787, living under Spanish rule, Fish wrote to the British prime minister in the hopes of being relocated, or getting some kind of compensation. Can't hurt to ask. Fish introduces himself as "an individual that is reduced to a very distressfull and unhappy situation; and at a period of life, aflicted with bodily infirmities, that renders him quite unfitt, and unable to encounter difficulties." He recounts the story of his life in Florida--"this unfortunate country (for me)," arriving as a boy in 1735. In the 1750s, he earned "a considerable sum of money" as a supplier to the Spanish garrison in St. Augustine, but spent most of it "to assist the needy and relieve the distressed . . . as many boath English and American vessells were frequently wrecked on the Florida coast as they were a coming through the gulph." When the Spanish were expelled in 1763, he assumed the debts of many friends rather than see them detained. By the time of the Revolution, he owned considerable real estate in the city, which "I had soon after the mortification to see torn down by the soldiers to burn . . . without being able to obtain the least satisfaction from Major James Oglivie of the 9th Reg'mt." After the war, the new British governor of Florida Grant decreed that all old British purchases of land from Spanish citizens would be null and void, further weakening his finances. An agent sent to London to negotiate for this land spent years in court and died before resolution was reached. Fish remained in Florida when the Spanish resumed control in 1783: "It may be asked how or why I have continued here after the evacuation. I answer my poverty and age, and I have a son that I earnestly wish to give as much education to as may prepare him the better to shift for himself. . . . I am here only on sufferance, as to become a Spanish subject is the last thing in life I would do. . . . I must now with the utmost regret leave it soon to undergo the last severe tryall in life on the Bahamas Islands (or rather rocks) without wherewithal to subsist upon or the means to raise it. A few slaves that I have at present in possession are not mine, but lent me by a brother-in-law. . . . My maloncholy prospect is to perrish before I can obtain relief except it comes very soon."

At this point, the Prime Minister might have taken a deep breath and asked, "Well, what do you want from me?" In conclusion, Fish expresses his faith "that through your kind and indulgent patronage I shall obtain the relief that my unhappy case has a just right to expect, which will ever fill the heart with gratitude."

This remarkable letter is apparently unpublished and unknown to scholarship. We have found no indication that Pitt responded to this entreaty, let alone granted anything to Fish. Two years later, Fish wrote another similar plea to the King of Spain, which is well-known to history. He died in St. Augustine in 1790.

Exhibition Hours

Exhibition Hours

Aliquam vulputate ornare congue. Vestibulum maximus, libero in placerat faucibus, risus nisl molestie massa, ut maximus metus lectus vel lorem.