Sale 2615 - Lot 260

Price Realized: $ 230,000

Price Realized: $ 281,000

?Final Price Realized includes Buyer’s Premium added to Hammer Price

Estimate: $ 60,000 - $ 90,000

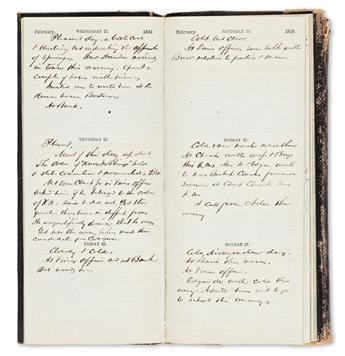

(GIDEON WELLES.) Extensive archive of personal and family papers of Lincoln's Secretary of the Navy. More than 1,000 items in 6 boxes (2.5 linear feet), including approximately 153 Autograph Letters Signed by Gideon Welles, 1823-1877; approximately 238 letters to Gideon Welles, most from close family members, circa 1822-1872; 4 manuscript diaries by Welles covering parts of 1836, 1844, 1852, and 1855; and additional family manuscripts, photographs and printed ephemera. Condition is generally strong; a faint tobacco scent can be noted, and less than 5% of the collection suffered moderate damage from an 1897 fire in the family's Hartford home, but the great bulk of papers are unaffected. Various places, 1791-1914, bulk circa 1836-1877

Additional Details

Gideon Welles (1802-1878) was chosen by President Lincoln as his Secretary of the Navy in 1861, and remained in office through the end of Andrew Johnson's term in 1869. Under his leadership, the Union Navy blockaded Southern ports, proceeded up the Mississippi River, and played a major role in crushing the Confederacy.

Welles was born and raised in Glastonbury, Connecticut, where he spent most of his life. He was an early graduate of what became Norwich University in Vermont, and returned to Connecticut to practice law, edit a newspaper, and serve in the state legislature. His highest-profile position before the Civil War was as Chief of the Bureau of Provisions and Clothing for the Navy during the period of the Mexican-American War. He opposed slavery and became an early member of the new Republican Party in 1854.

This large and substantial archive contains the personal correspondence, diaries, and manuscripts of Gideon Welles, as well as family correspondence, printed ephemera, and photographs. At the heart of the collection are 153 of his Autograph Letters Signed, almost all of them to his son Thomas Glastonbury Welles (1846-1892), with most of them written during the war years. At the outset of the war, Thomas was 14 years old. Shortly before Fort Sumter, Gideon urges Thomas: "The man who will not stand by his country in the hour of peril will not deserve respect" (7 April 1861). He worked to discourage Thomas from prematurely joining the Navy: "No man can be a ship master, or anything but a working drudge of a sailor--the lowest class--without an education" (9 February 1862). While Gideon mentioned the ominous Confederate incursion into Maryland to Thomas, he went into more detail in a 7 September 1862 partial letter to his wife Mary Jane: "We have information that the Rebels had crossed the Upper Potomac in considerable force. . . . They are on this side full sixty five thousand strong, nearly one half their force having reached Frederick. . . . Not less than two hundred regiments passed our door last night between 10 and 1 o'clock. The street was a mass of living men, moving rapidly forward all that time."

When Thomas joined the Naval Academy and was posted on the famed USS Constitution for training, Gideon wrote "There have been many good and brave and true hearts on her deck. May you be as worthy" (1 October 1862). As the war progressed and Thomas matured, Gideon shared more insights into military matters. Shortly after the USS Monitor was lost in a storm, he wrote "The loss of the Monitor gave us pain, for she had won herself a name and character that endeared her more to us than a more costly vessel." In reaction to General McClellan's presidential campaign against Lincoln, Welles dismissed his military accomplishments: "He accomplished very little, and seemed indisposed to take advantage of success. . . . He thought more of himself than the country, and tried to have them engage for him rather than the war" (18 August 1864)." Thomas left the Naval Academy to join the Army as a young officer. Welles expressed concern about his new commander Godfrey Weitzel: "He has a fair reputation as an officer, but I have an impression that he sometimes drank more whiskey than he should" (10 October 1864).

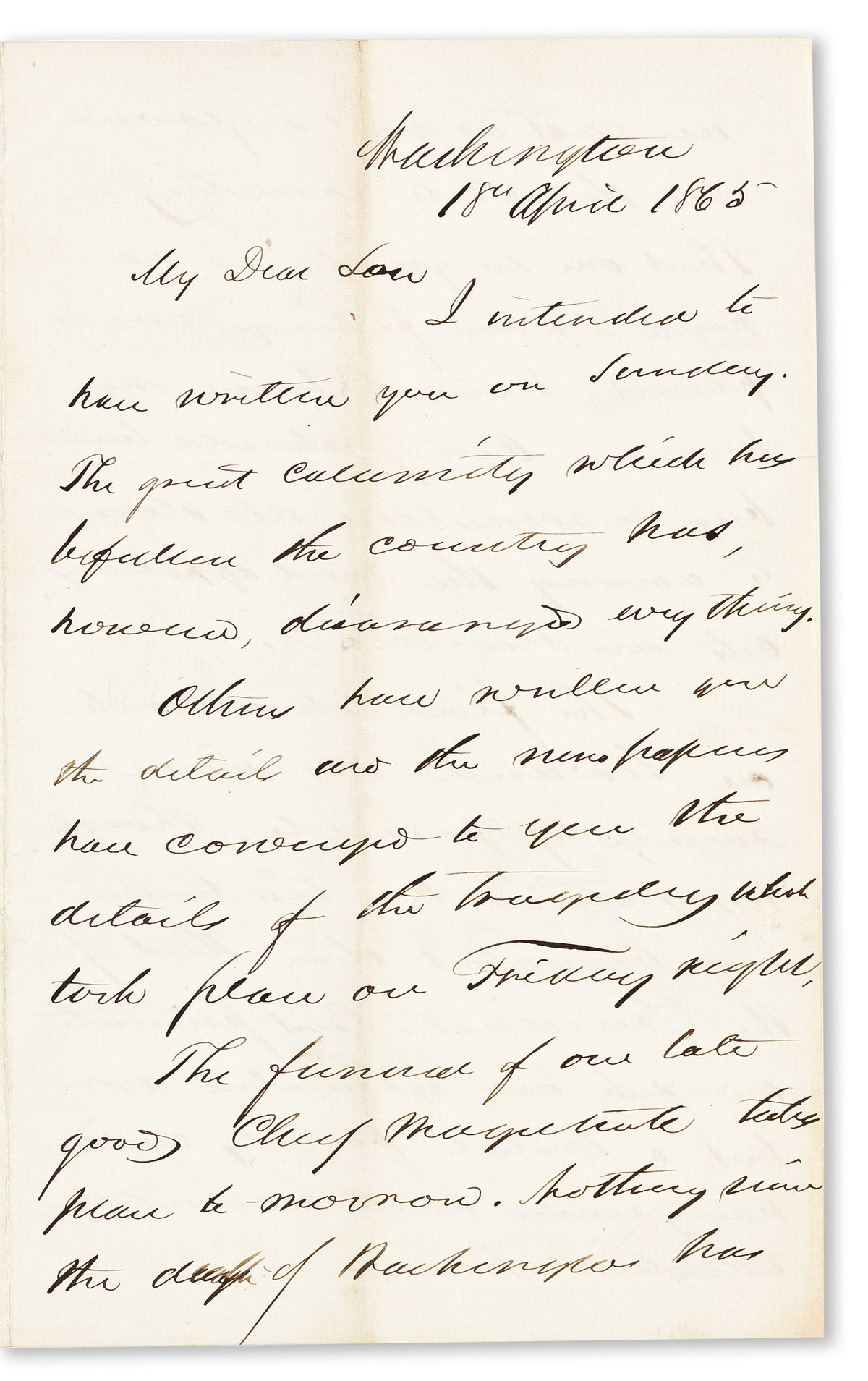

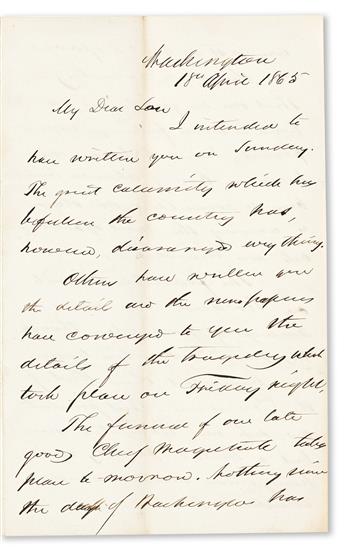

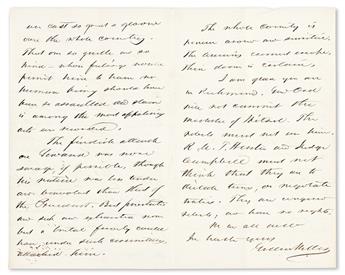

Welles wrote several letters to Thomas during the dramatic conclusion of the war. On 14 April, the Secretary was (like most of the north) in a state of relief: "Last evening all Washington was in a blaze of illumination, fire-works and displays commemorative of the great victory. The truth is we have been doing little else than rejoicing for the last ten days." By 18 April, the mood had changed: "Nothing since the death of Washington has ever cast so great a gloom over the whole country. That one so gentle, and so kind, whose feelings would permit him to harm no human being, should have been so assaulted and slain is among the most appalling acts ever recorded." On 20 April he offered a fuller tribute: "His gentle virtues and noble qualities will grow brighter with time, and the world will better appreciate him in the future than while he was among us. Few such men have ever lived. No finer or better man ever stood at the head of a nation. I knew him well and was honored by his friendship, and it will be one of the treasured memories of my life." On 25 April, he reported on his wife Mary Jane Hale Welles (1817-1886), one of the First Lady's closest friends: "Your mother spends a portion of every day with Mrs. Lincoln, who has not recovered from the terrible shock which prostrated her."

Gideon's 29 postwar letters to Thomas are also interesting, particularly for his perspective on President Andrew Johnson. Welles was one of Johnson's few loyal supporters in Washington. During the impeachment proceedings, he raged "If the Radicals by fraud or force or both shall attempt to continue in power against the popular sentiment, strife and desolation will follow. . . . I detest them almost as much as the secessionists" (3 May 1868). Upon Johnson's death, he reflected on 5 August 1875: "Johnson was an honest man, and a true constitutionalist, with fearless moral & physical courage."

The collection also contains approximately 238 letters received by Welles, the majority of them from family members. As a young aide-de-camp on the day after the Battle of the Crater, Thomas wrote a great war letter in its own right: "We proceeded at 3 a.m. to the trenches to await the explosion of Burnside's mine. . . . It arose some one or two hundred feet, sending up earth, stones and a whole regiment or more of rebels. . . . The darkies made a very good charge, but it soon became too heavy for them. . . . I was in front of the support and running with all my might towards what appeared almost certain death. It was impossible to retreat. . . . A shell struck within twenty feet of us, killing a captain and wounding several more. . . . A sudden sort of spasm succeeded by a loud explosion and finishing with a ringing in my ears, and a thought that I had been hit in the back of my head succeeded, and for ten or fifteen seconds I was perfectly insensible" (1 August 1864). Thomas also wrote several letters in the wake of the Lincoln assassination, urging his father to exercise caution: "Have a sentry from Marine Guard at your door, and be careful who you see" (16 April 1865). A few of the letters are from official correspondents, including 3 from General Edward O.C. Ord re Thomas G. Welles joining his staff, 1864-1865; Robert Todd Lincoln, 1869; Horace Binney Sergeant, 1872 (requesting "the official facts of the expedition under Admiral Farragut against New Orleans and Mobile"); Edward Everett (as "E.E."), 1862, and Rear Admiral David D. Porter, 1864. Two anonymous letters from 1863 (24 February and 6 June) discuss Confederate blockade runners.

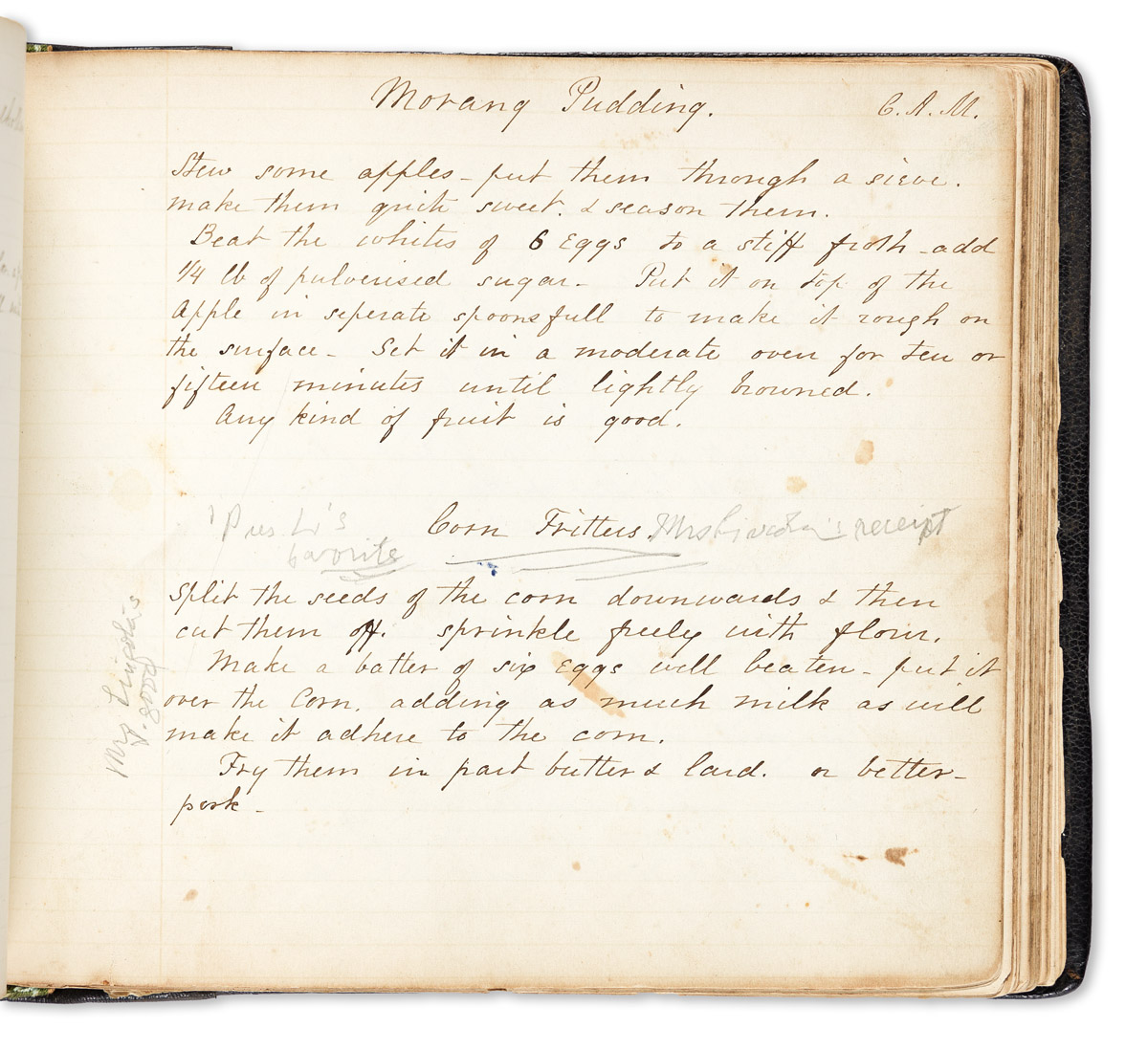

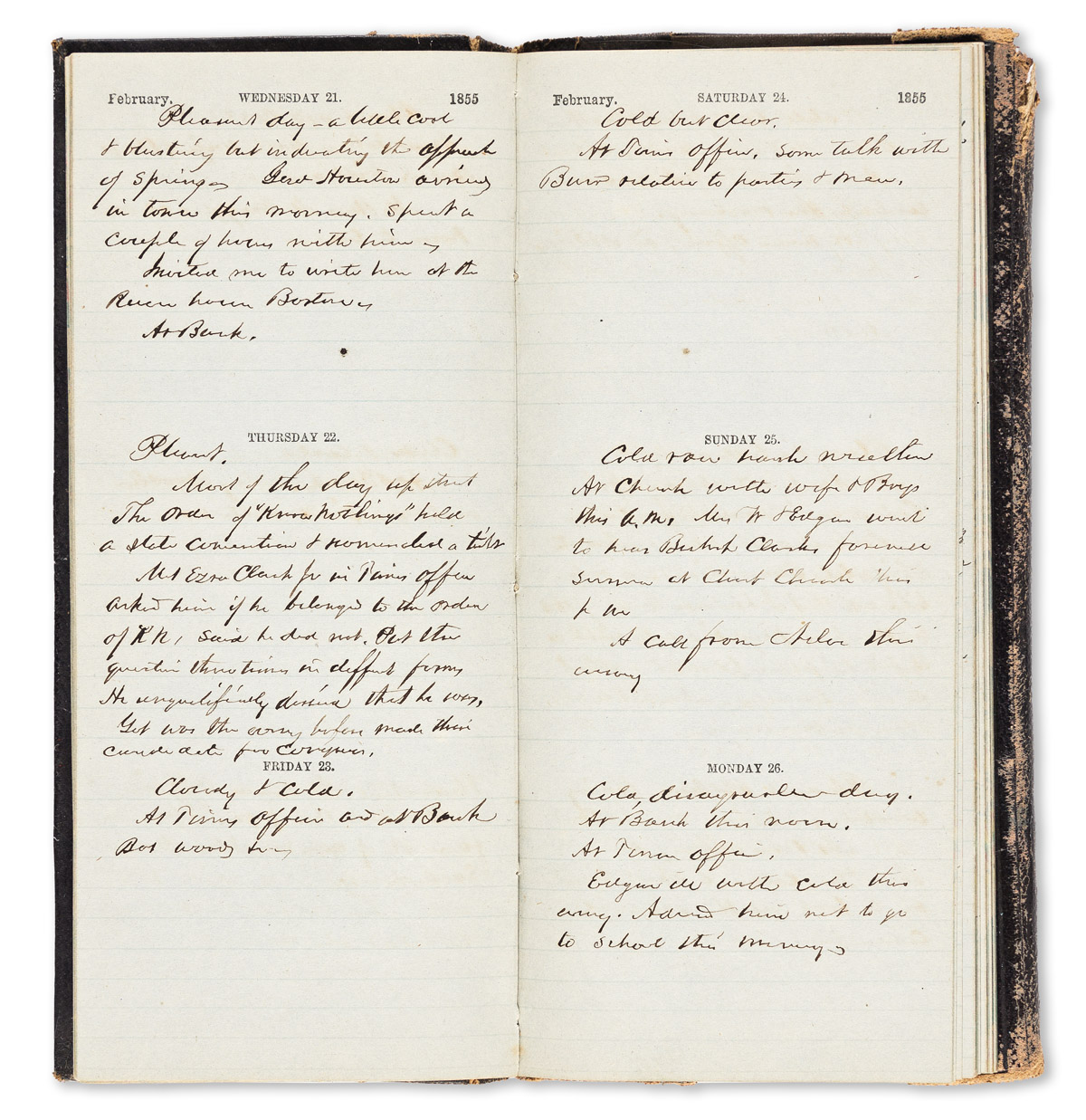

The collection includes four pre-war diaries by Welles, dated 1836, 1844, 1852, and 1855, all rich in political talk. The 1844 diary only covers two weeks in April, but is perhaps the most interesting. John Milton Niles (1787-1856), a political mentor and friend of Welles, had been elected to the United States Senate in 1842, but before he could take office, the death of his wife triggered a nervous breakdown, and he was committed to an asylum. By April 1844, Niles had been released, and Welles accompanied him as moral support on the terrifying journey to Washington to assume his place in the Senate. On 11 April, Niles made his first appearance in Congress: "Mr. Buchanan, he thought, & not without reason, treated him coldly. . . . Niles had hoped for a warm & friendly greeting from B and expected that he if anyone would earnestly & cordially welcome him into the Senate." Two days later, "one of the reporters enquired of Bigelow so loud as to have him hear, whether he was still crazy." On 14 April, "he told me of the delusions he had experienced, and seems not yet willing fully to admit they were delusions." This diary is a fascinating look at the perceptions of mental health struggles in the halls of power. The 1852 and 1855 diaries are steeped in local Connecticut politics and real estate deals, including repeated clashes with Hartford's most famous arms manufacturer: "Some talk with sundry persons respecting Sam Colt, who is either playing a game or is exceedingly stupid" (11 March 1852). In 1855, he expressed disgust at the emergence of the Know-Nothing Party in Connecticut: "The order of Know-Nothings held a state convention & nominated a ticket. Met Ezra Clark Jr. in Paine's office, asked him if he belonged to the order of KN, said he did not. Put the question three times in different forms. He unqualifiedly denied that he was. Yet was the evening before made their candidate for Congress" (22 February).

A box of manuscripts by and about Welles contains some treasures. An undated political essay includes a long denunciation of President Grant: "It was a matter of amazement to me that a person who had his opportunities was so unfamiliar with the practical workings of our political system. . . . He is, beyond the ordinary run of men, deficient in civil administrative capacity and intelligence"; Admiral Foote said "he preferred Grant [above other generals] notwithstanding his insignificant personal appearance, provided he would let whiskey alone." Juvenile manuscripts go back to 1817 and probably earlier; a certificate of merit he received is from circa 1809. A 24-page biography of Welles in calligraphic hand with carte-de-visite portrait of Welles is dated September 1862; his quite worn commission on vellum as chief of the Bureau of Provisions is signed by President James Polk, 1846.

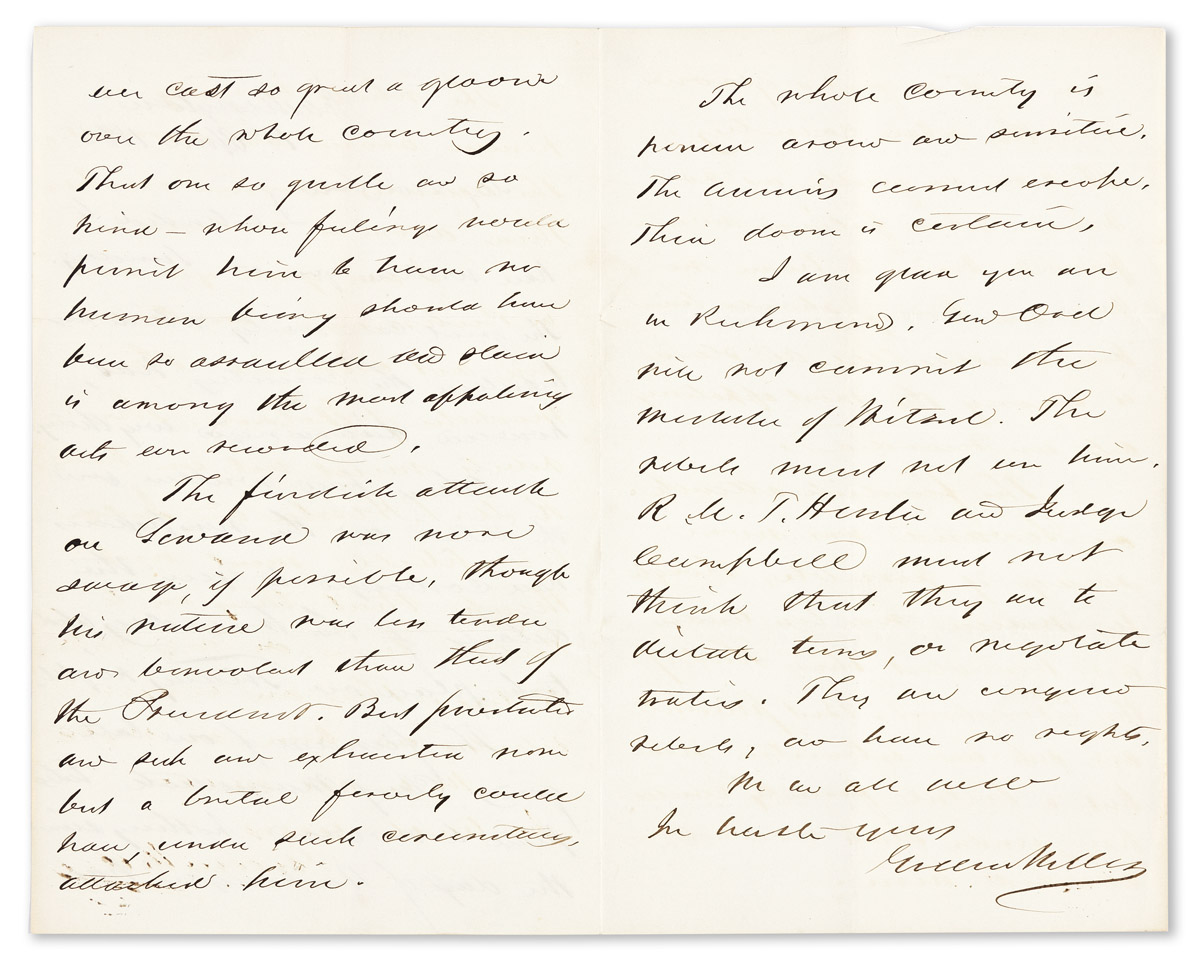

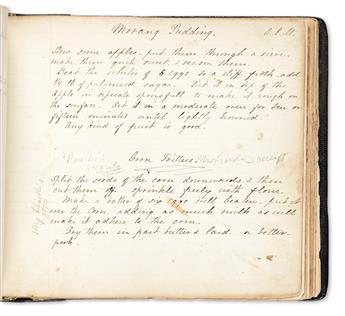

Gideon's wife Mary Jane Hale Welles is represented by her personal manuscript recipe book dated 1869, rendered more interesting by notations on her famous friends. Corn starch pudding and charlotte russe are noted "From Mrs. Lincoln"; corn fritters are marked "Pres L's favorite, Mrs. Lincoln's receipt, Mrs. Lincoln's, good"; at end, corn soup is marked "Pres. Johnson's" and potato soup just below is marked "Pres. Johnson's favorite." Also included is a manuscript invitation from Mr. Lincoln at the Executive Mansion (not in Lincoln's hand). Among the letters received by son Edgar Thaddeus Welles are 3 from Admiral David G. Farragut, who wrote on 28 September 1863 from Hastings, NY: "At Sabine Pass, the soldiers no doubt overruled the officers of the navy to violate their instructions. When the soldiers were sent down to Galveston by Gen'l Banks, I instructed them to land upon Pelican Island where the gunboats could protect them, instead of which Bingham & the soldiers determined to land on the wharf at Galveston, where they were all captured." Edgar's scrapbook of newspaper clippings on his father's cabinet career is also included. Other papers of family members include Yale essays and correspondence of father-in-law Elias White Hale dating back to 1792. Son Edgar was an autograph collector. A folder of 28 letters, clipped signatures, and autograph book entries includes William Seward and many other prominent politicians of the 1850s and 1860s. An album of mostly clipped signatures includes Presidents Madison, Polk, Pierce, Buchanan, Johnson, and Grant among many others, and another album contains signatures of most of the senators in the 25th Congress including Franklin Pierce, Daniel Webster, James Buchanan, John C. Calhoun, and Henry Clay, as well as President Martin Van Buren and 5 cabinet members. The collection also includes 62 checks bearing the signature of Welles, as well as 10 envelopes bearing his franking signature. One prized heirloom was the appointment of son Thomas Welles as Navy midshipman in November 1862, signed by his father as Secretary of the Navy.

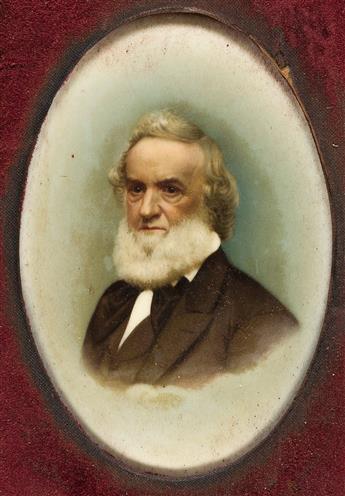

Graphic material includes a miniature watercolor portrait of Welles, 4 x 2 1/2 inches oval; approximately 95 photographs depicting mostly family members and Civil War-era celebrities (most in carte-de-visite or cabinet-card formats); and an untitled and unsigned pencil sketch of an ironclad ship. Printed material includes an 1831 Bible signed by Gideon Welles on flyleaf; a worn memorial pamphlet "State Council of Pennsylvania, O. of U.A.M., In Memoriam Abraham Lincoln," gilt-stamped on front cover for "Hon. Gideon Welles, Secretary of the Navy"; and a broadside seating chart for Delmonico's, "Dinner to the President of the United States in Honor of his Visit to the City of New York, August 29th, 1866." A pair of leather portfolios, one gilt-stamped "Gideon Welles," the other "Gideon Welles, Secretary of the Navy," are included. For those anxious to know more about the shape of Welles's skull, see L.N. Fowler's "Synopsis of Phrenology" pamphlet annotated with a full report dated 1845. The family saved large quantities of invitations, calling cards, and similar ephemera, perhaps 200 items, from the 1820s-1870s. Many are inserted into a large black album. Highlights include a Civil War pass issued to "Gideon Welles and Friends" dated 6 May 1864; a ticket for the 1865 Grand Review of Troops issued by General Augur; a ticket to "Mr. Bancroft's Eulogy" on Lincoln in Congress, 1866; an engraved undated invitation from "The President" to Welles (possibly Buchanan as no wife is noted); an engraved invitation from Andrew Johnson to Gideon and Mrs. Welles, 8 February 1868; a pair of Mrs. Andrew Johnson calling cards; a pair of William Seward engraved invitations; and a ticket to a "Citizen's Reception to his Excellency President Johnson."

A more detailed inventory of this nationally significant archive is available upon request. Provenance: from the collection of Thomas Welles Brainard, great-great-grandson of Gideon Welles.

Welles was born and raised in Glastonbury, Connecticut, where he spent most of his life. He was an early graduate of what became Norwich University in Vermont, and returned to Connecticut to practice law, edit a newspaper, and serve in the state legislature. His highest-profile position before the Civil War was as Chief of the Bureau of Provisions and Clothing for the Navy during the period of the Mexican-American War. He opposed slavery and became an early member of the new Republican Party in 1854.

This large and substantial archive contains the personal correspondence, diaries, and manuscripts of Gideon Welles, as well as family correspondence, printed ephemera, and photographs. At the heart of the collection are 153 of his Autograph Letters Signed, almost all of them to his son Thomas Glastonbury Welles (1846-1892), with most of them written during the war years. At the outset of the war, Thomas was 14 years old. Shortly before Fort Sumter, Gideon urges Thomas: "The man who will not stand by his country in the hour of peril will not deserve respect" (7 April 1861). He worked to discourage Thomas from prematurely joining the Navy: "No man can be a ship master, or anything but a working drudge of a sailor--the lowest class--without an education" (9 February 1862). While Gideon mentioned the ominous Confederate incursion into Maryland to Thomas, he went into more detail in a 7 September 1862 partial letter to his wife Mary Jane: "We have information that the Rebels had crossed the Upper Potomac in considerable force. . . . They are on this side full sixty five thousand strong, nearly one half their force having reached Frederick. . . . Not less than two hundred regiments passed our door last night between 10 and 1 o'clock. The street was a mass of living men, moving rapidly forward all that time."

When Thomas joined the Naval Academy and was posted on the famed USS Constitution for training, Gideon wrote "There have been many good and brave and true hearts on her deck. May you be as worthy" (1 October 1862). As the war progressed and Thomas matured, Gideon shared more insights into military matters. Shortly after the USS Monitor was lost in a storm, he wrote "The loss of the Monitor gave us pain, for she had won herself a name and character that endeared her more to us than a more costly vessel." In reaction to General McClellan's presidential campaign against Lincoln, Welles dismissed his military accomplishments: "He accomplished very little, and seemed indisposed to take advantage of success. . . . He thought more of himself than the country, and tried to have them engage for him rather than the war" (18 August 1864)." Thomas left the Naval Academy to join the Army as a young officer. Welles expressed concern about his new commander Godfrey Weitzel: "He has a fair reputation as an officer, but I have an impression that he sometimes drank more whiskey than he should" (10 October 1864).

Welles wrote several letters to Thomas during the dramatic conclusion of the war. On 14 April, the Secretary was (like most of the north) in a state of relief: "Last evening all Washington was in a blaze of illumination, fire-works and displays commemorative of the great victory. The truth is we have been doing little else than rejoicing for the last ten days." By 18 April, the mood had changed: "Nothing since the death of Washington has ever cast so great a gloom over the whole country. That one so gentle, and so kind, whose feelings would permit him to harm no human being, should have been so assaulted and slain is among the most appalling acts ever recorded." On 20 April he offered a fuller tribute: "His gentle virtues and noble qualities will grow brighter with time, and the world will better appreciate him in the future than while he was among us. Few such men have ever lived. No finer or better man ever stood at the head of a nation. I knew him well and was honored by his friendship, and it will be one of the treasured memories of my life." On 25 April, he reported on his wife Mary Jane Hale Welles (1817-1886), one of the First Lady's closest friends: "Your mother spends a portion of every day with Mrs. Lincoln, who has not recovered from the terrible shock which prostrated her."

Gideon's 29 postwar letters to Thomas are also interesting, particularly for his perspective on President Andrew Johnson. Welles was one of Johnson's few loyal supporters in Washington. During the impeachment proceedings, he raged "If the Radicals by fraud or force or both shall attempt to continue in power against the popular sentiment, strife and desolation will follow. . . . I detest them almost as much as the secessionists" (3 May 1868). Upon Johnson's death, he reflected on 5 August 1875: "Johnson was an honest man, and a true constitutionalist, with fearless moral & physical courage."

The collection also contains approximately 238 letters received by Welles, the majority of them from family members. As a young aide-de-camp on the day after the Battle of the Crater, Thomas wrote a great war letter in its own right: "We proceeded at 3 a.m. to the trenches to await the explosion of Burnside's mine. . . . It arose some one or two hundred feet, sending up earth, stones and a whole regiment or more of rebels. . . . The darkies made a very good charge, but it soon became too heavy for them. . . . I was in front of the support and running with all my might towards what appeared almost certain death. It was impossible to retreat. . . . A shell struck within twenty feet of us, killing a captain and wounding several more. . . . A sudden sort of spasm succeeded by a loud explosion and finishing with a ringing in my ears, and a thought that I had been hit in the back of my head succeeded, and for ten or fifteen seconds I was perfectly insensible" (1 August 1864). Thomas also wrote several letters in the wake of the Lincoln assassination, urging his father to exercise caution: "Have a sentry from Marine Guard at your door, and be careful who you see" (16 April 1865). A few of the letters are from official correspondents, including 3 from General Edward O.C. Ord re Thomas G. Welles joining his staff, 1864-1865; Robert Todd Lincoln, 1869; Horace Binney Sergeant, 1872 (requesting "the official facts of the expedition under Admiral Farragut against New Orleans and Mobile"); Edward Everett (as "E.E."), 1862, and Rear Admiral David D. Porter, 1864. Two anonymous letters from 1863 (24 February and 6 June) discuss Confederate blockade runners.

The collection includes four pre-war diaries by Welles, dated 1836, 1844, 1852, and 1855, all rich in political talk. The 1844 diary only covers two weeks in April, but is perhaps the most interesting. John Milton Niles (1787-1856), a political mentor and friend of Welles, had been elected to the United States Senate in 1842, but before he could take office, the death of his wife triggered a nervous breakdown, and he was committed to an asylum. By April 1844, Niles had been released, and Welles accompanied him as moral support on the terrifying journey to Washington to assume his place in the Senate. On 11 April, Niles made his first appearance in Congress: "Mr. Buchanan, he thought, & not without reason, treated him coldly. . . . Niles had hoped for a warm & friendly greeting from B and expected that he if anyone would earnestly & cordially welcome him into the Senate." Two days later, "one of the reporters enquired of Bigelow so loud as to have him hear, whether he was still crazy." On 14 April, "he told me of the delusions he had experienced, and seems not yet willing fully to admit they were delusions." This diary is a fascinating look at the perceptions of mental health struggles in the halls of power. The 1852 and 1855 diaries are steeped in local Connecticut politics and real estate deals, including repeated clashes with Hartford's most famous arms manufacturer: "Some talk with sundry persons respecting Sam Colt, who is either playing a game or is exceedingly stupid" (11 March 1852). In 1855, he expressed disgust at the emergence of the Know-Nothing Party in Connecticut: "The order of Know-Nothings held a state convention & nominated a ticket. Met Ezra Clark Jr. in Paine's office, asked him if he belonged to the order of KN, said he did not. Put the question three times in different forms. He unqualifiedly denied that he was. Yet was the evening before made their candidate for Congress" (22 February).

A box of manuscripts by and about Welles contains some treasures. An undated political essay includes a long denunciation of President Grant: "It was a matter of amazement to me that a person who had his opportunities was so unfamiliar with the practical workings of our political system. . . . He is, beyond the ordinary run of men, deficient in civil administrative capacity and intelligence"; Admiral Foote said "he preferred Grant [above other generals] notwithstanding his insignificant personal appearance, provided he would let whiskey alone." Juvenile manuscripts go back to 1817 and probably earlier; a certificate of merit he received is from circa 1809. A 24-page biography of Welles in calligraphic hand with carte-de-visite portrait of Welles is dated September 1862; his quite worn commission on vellum as chief of the Bureau of Provisions is signed by President James Polk, 1846.

Gideon's wife Mary Jane Hale Welles is represented by her personal manuscript recipe book dated 1869, rendered more interesting by notations on her famous friends. Corn starch pudding and charlotte russe are noted "From Mrs. Lincoln"; corn fritters are marked "Pres L's favorite, Mrs. Lincoln's receipt, Mrs. Lincoln's, good"; at end, corn soup is marked "Pres. Johnson's" and potato soup just below is marked "Pres. Johnson's favorite." Also included is a manuscript invitation from Mr. Lincoln at the Executive Mansion (not in Lincoln's hand). Among the letters received by son Edgar Thaddeus Welles are 3 from Admiral David G. Farragut, who wrote on 28 September 1863 from Hastings, NY: "At Sabine Pass, the soldiers no doubt overruled the officers of the navy to violate their instructions. When the soldiers were sent down to Galveston by Gen'l Banks, I instructed them to land upon Pelican Island where the gunboats could protect them, instead of which Bingham & the soldiers determined to land on the wharf at Galveston, where they were all captured." Edgar's scrapbook of newspaper clippings on his father's cabinet career is also included. Other papers of family members include Yale essays and correspondence of father-in-law Elias White Hale dating back to 1792. Son Edgar was an autograph collector. A folder of 28 letters, clipped signatures, and autograph book entries includes William Seward and many other prominent politicians of the 1850s and 1860s. An album of mostly clipped signatures includes Presidents Madison, Polk, Pierce, Buchanan, Johnson, and Grant among many others, and another album contains signatures of most of the senators in the 25th Congress including Franklin Pierce, Daniel Webster, James Buchanan, John C. Calhoun, and Henry Clay, as well as President Martin Van Buren and 5 cabinet members. The collection also includes 62 checks bearing the signature of Welles, as well as 10 envelopes bearing his franking signature. One prized heirloom was the appointment of son Thomas Welles as Navy midshipman in November 1862, signed by his father as Secretary of the Navy.

Graphic material includes a miniature watercolor portrait of Welles, 4 x 2 1/2 inches oval; approximately 95 photographs depicting mostly family members and Civil War-era celebrities (most in carte-de-visite or cabinet-card formats); and an untitled and unsigned pencil sketch of an ironclad ship. Printed material includes an 1831 Bible signed by Gideon Welles on flyleaf; a worn memorial pamphlet "State Council of Pennsylvania, O. of U.A.M., In Memoriam Abraham Lincoln," gilt-stamped on front cover for "Hon. Gideon Welles, Secretary of the Navy"; and a broadside seating chart for Delmonico's, "Dinner to the President of the United States in Honor of his Visit to the City of New York, August 29th, 1866." A pair of leather portfolios, one gilt-stamped "Gideon Welles," the other "Gideon Welles, Secretary of the Navy," are included. For those anxious to know more about the shape of Welles's skull, see L.N. Fowler's "Synopsis of Phrenology" pamphlet annotated with a full report dated 1845. The family saved large quantities of invitations, calling cards, and similar ephemera, perhaps 200 items, from the 1820s-1870s. Many are inserted into a large black album. Highlights include a Civil War pass issued to "Gideon Welles and Friends" dated 6 May 1864; a ticket for the 1865 Grand Review of Troops issued by General Augur; a ticket to "Mr. Bancroft's Eulogy" on Lincoln in Congress, 1866; an engraved undated invitation from "The President" to Welles (possibly Buchanan as no wife is noted); an engraved invitation from Andrew Johnson to Gideon and Mrs. Welles, 8 February 1868; a pair of Mrs. Andrew Johnson calling cards; a pair of William Seward engraved invitations; and a ticket to a "Citizen's Reception to his Excellency President Johnson."

A more detailed inventory of this nationally significant archive is available upon request. Provenance: from the collection of Thomas Welles Brainard, great-great-grandson of Gideon Welles.

Exhibition Hours

Exhibition Hours

Aliquam vulputate ornare congue. Vestibulum maximus, libero in placerat faucibus, risus nisl molestie massa, ut maximus metus lectus vel lorem.