Sale 2534 - Lot 284

Price Realized: $ 1,000

Price Realized: $ 1,250

?Final Price Realized includes Buyer’s Premium added to Hammer Price

Estimate: $ 800 - $ 1,200

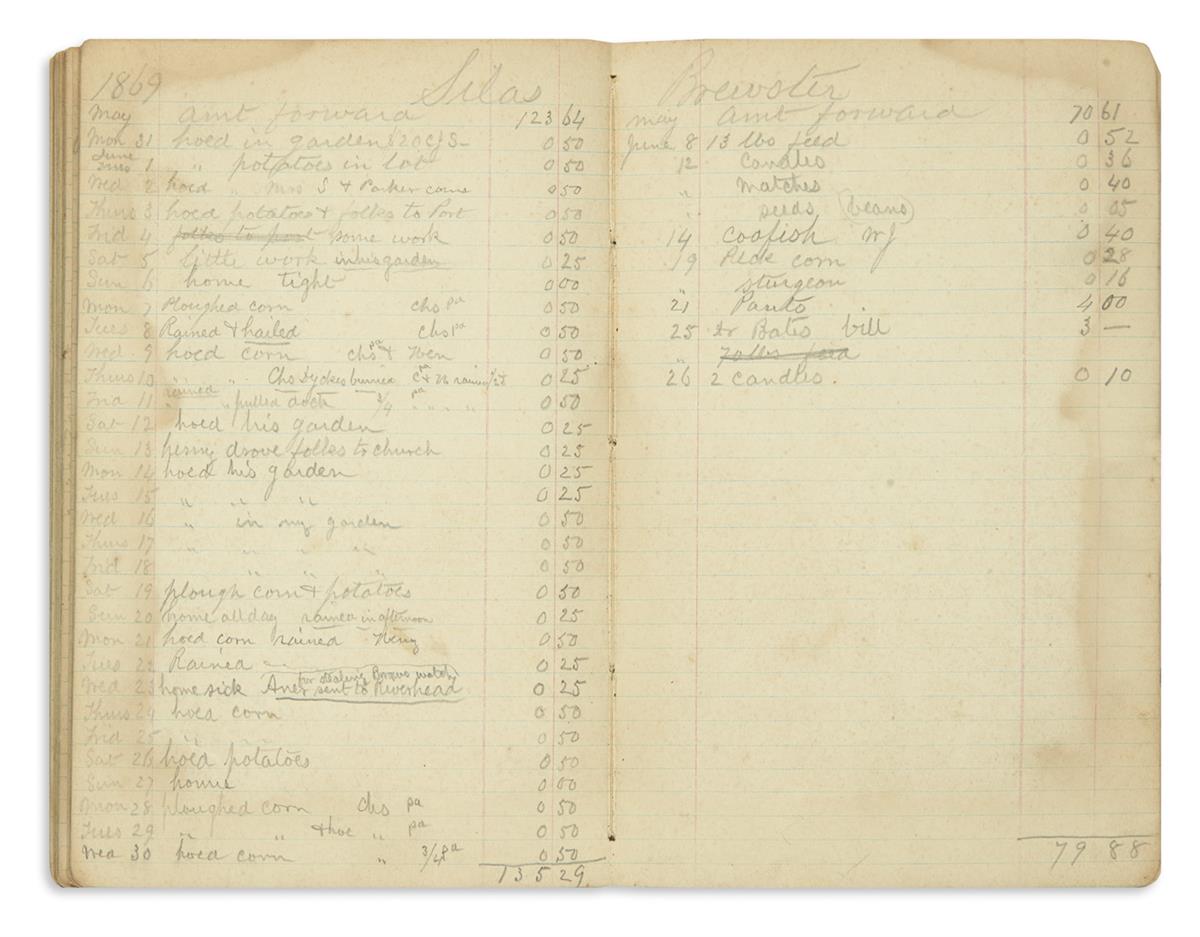

(LABOR.) Daily ledger of accounts with laborer Silas Brewster on Long Island. [120] manuscript pages of daily accounts with Silas Brewster, plus [8] unrelated memorandum pages. Large 8vo, 9 x 5 1/2 inches, original limp calf, worn with backstrip split, manuscript title 'Help's Book' on front cover; minor wear and dampstaining to contents. Setauket, NY, 1865-70

Additional Details

This slim volume documents the daily activities of a man named Silas Brewster (circa 1810-1877), as recorded by his employer in Setauket, NY on the north shore of Long Island. Setauket has long been known for its large mixed-race community, with roots among the Setalcott Indians as well as Africa, which has recently been recognized as the Bethel-Christian Avenue-Laurel Hill Historical District. Census records in 1860, 1865, and 1870 show Brewster as a black man, born in New York, living with his wife Phebe and several children, giving his occupation as 'farm laborer,' 'laborer,' and 'common laborer.' This 'Help's Book' explains what this laborer's working life consisted of during this time and place. The variety of work performed was quite broad; typical daily entries read 'corn stumps,' 'cart manure,' 'dig potatoes,' 'cart seaweed' (for fertilizer), 'setting sign posts,' 'getting stones out of lot,' 'hog pen,' and more. Driving a cart or carriage seemed to be the most common occupation, either delivering produce to nearby towns or transporting the employer's family members on excursions; sleighing was a popular winter pastime. Brewster was commonly paid to attend funerals, which seems unusual—we suspect he was transporting his employer or other local families to and from the church and cemetery. Most notable among the funerals was a 21 November 1868 entry: 'W.S. Mount buried, 60 y, 11 mo.' William Sidney Mount was perhaps Long Island's most famous artist of the mid-19th century. Mount's best-known painting was 'Eel Spearing at Setauket' in 1845, featuring an African-American servant at work spearing eels under the watchful eye of a small white boy.

Every day of Brewster's life is accounted for, even Sundays, which are usually marked 'no work.' Brewster received up to one dollar each day, most often 25 or 50 cents but varying widely depending on the amount and quality of work performed. Even his activities on his days off are often noted, particularly if Brewster worked on his own account—at the shore clamming or eeling much like William Sidney Mount had depicted, for example, or tending a small patch of his own turnips on his employer's land. On at least 30 occasions, Brewster's employer has written 'drunk' or some variant ('Tight in morn, sober at night' on 25 August 1867, for example), often with an underline or two to emphasize his disapproval.

While the left side of each spread records Brewster's daily work and his wages, the right side is devoted to his compensation. Most of it seems to have come as credit at the employer's general store for tobacco, calf's heads, candles, and other sundries. Brewster bought an eel spear on 11 February 1865. He also paid $25 in house rent every 15 May, showing that he lived on his employer's land. Brewster's family members make occasional appearances in this section; he was charged $6.00 for 'money to Phebe for shawl' on 23 December 1865, and $11.00 for 'Phoebe's dress' on 13 July 1866, for example. His daughter Aner, born circa 1855, is mentioned several times—her school bill is charged on 8 April 1867. The saddest entry in the ledger is on 23 June 1869: 'Aner sent to Riverhead for stealing Brow's watch.' Riverhead was then (and now) home to the Suffolk County jail. Brewster was fronted $7 to travel to Riverhead to see his daughter on 12 July, and spent 2 1/2 days there. We don't know the disposition of Aner's legal case, but she seems to have died in 1873 at the age of 18.

Brewster's employer was apparently Walter Smith (1833-1887), a white farmer and merchant who appears next door to Silas Brewster in the 1865 and 1870 censuses. Several of his family details match this ledger. On 23 December 1866, the ledger reads 'To station with Marco & me.' Walter Smith had a 7-year-old son named Marco. On 5 September 1866, he wrote 'Grandmother Dickerson died.' Walter Smith's wife Cornelia Hartt Smith lost her grandmother Sarah Jones Dickerson on that day. In addition to running a general store and farm, Smith was also involved in transport; he was listed as the proprietor of a stagecoach line from the Setauket train station to Old Field Point in an 1882 railroad guide, which seems to fit with Brewster's frequent employment in transporting Smith's neighbors.

This volume is a prime example of the importance—and the pitfalls—of researching African-American history. It provides us an uncommonly detailed perspective on the life of a struggling 'common laborer' just after the Civil War, the kind of person who often does not have his own voice in history. But, unfortunately, Silas Brewster still does not have his own voice—he has the somewhat sympathetic, somewhat condescending voice of his white employer. The challenge is to read between the lines to see Brewster's perspective. If you want to understand Silas Brewster's life, this narrative is a long way from perfect, but it is much better than nothing.

Every day of Brewster's life is accounted for, even Sundays, which are usually marked 'no work.' Brewster received up to one dollar each day, most often 25 or 50 cents but varying widely depending on the amount and quality of work performed. Even his activities on his days off are often noted, particularly if Brewster worked on his own account—at the shore clamming or eeling much like William Sidney Mount had depicted, for example, or tending a small patch of his own turnips on his employer's land. On at least 30 occasions, Brewster's employer has written 'drunk' or some variant ('Tight in morn, sober at night' on 25 August 1867, for example), often with an underline or two to emphasize his disapproval.

While the left side of each spread records Brewster's daily work and his wages, the right side is devoted to his compensation. Most of it seems to have come as credit at the employer's general store for tobacco, calf's heads, candles, and other sundries. Brewster bought an eel spear on 11 February 1865. He also paid $25 in house rent every 15 May, showing that he lived on his employer's land. Brewster's family members make occasional appearances in this section; he was charged $6.00 for 'money to Phebe for shawl' on 23 December 1865, and $11.00 for 'Phoebe's dress' on 13 July 1866, for example. His daughter Aner, born circa 1855, is mentioned several times—her school bill is charged on 8 April 1867. The saddest entry in the ledger is on 23 June 1869: 'Aner sent to Riverhead for stealing Brow's watch.' Riverhead was then (and now) home to the Suffolk County jail. Brewster was fronted $7 to travel to Riverhead to see his daughter on 12 July, and spent 2 1/2 days there. We don't know the disposition of Aner's legal case, but she seems to have died in 1873 at the age of 18.

Brewster's employer was apparently Walter Smith (1833-1887), a white farmer and merchant who appears next door to Silas Brewster in the 1865 and 1870 censuses. Several of his family details match this ledger. On 23 December 1866, the ledger reads 'To station with Marco & me.' Walter Smith had a 7-year-old son named Marco. On 5 September 1866, he wrote 'Grandmother Dickerson died.' Walter Smith's wife Cornelia Hartt Smith lost her grandmother Sarah Jones Dickerson on that day. In addition to running a general store and farm, Smith was also involved in transport; he was listed as the proprietor of a stagecoach line from the Setauket train station to Old Field Point in an 1882 railroad guide, which seems to fit with Brewster's frequent employment in transporting Smith's neighbors.

This volume is a prime example of the importance—and the pitfalls—of researching African-American history. It provides us an uncommonly detailed perspective on the life of a struggling 'common laborer' just after the Civil War, the kind of person who often does not have his own voice in history. But, unfortunately, Silas Brewster still does not have his own voice—he has the somewhat sympathetic, somewhat condescending voice of his white employer. The challenge is to read between the lines to see Brewster's perspective. If you want to understand Silas Brewster's life, this narrative is a long way from perfect, but it is much better than nothing.

Exhibition Hours

Exhibition Hours

Aliquam vulputate ornare congue. Vestibulum maximus, libero in placerat faucibus, risus nisl molestie massa, ut maximus metus lectus vel lorem.