Sale 2580 - Lot 158

Price Realized: $ 3,000

Price Realized: $ 3,750

?Final Price Realized includes Buyer’s Premium added to Hammer Price

Estimate: $ 1,500 - $ 2,500

(MARITIME.) Narrative by the supercargo of a smuggling vessel working around Jefferson's embargo. 29 manuscript pages, 13 x 7 1/2 inches, on 15 detached leaves; first and final leaves worn and toned with repaired tears, internal leaves with minor edge wear. Various places, 9 August 1808 to 17 March 1809

Additional Details

This intrepid merchant packed a lifetime's worth of adventure onto these 7 months and 29 pages. He was apparently experienced at sea, well versed in nautical language. He was not a ship's hand, though. He and his partner Le Gros were apparently supercargoes representing the ship's owners as traders. And the trading was apparently not quite legitimate, as they sailed on a ship of scoundrels against the backdrop of Jefferson's embargo and the looming war with the United Kingdom.

The journal begins with our narrator shipping out from Philadelphia, and getting involved in an elaborate hunt for one more crew member. One man having fallen ill in Philadelphia, they failed to find a replacement in New Castle, DE, and went across the river to New Jersey, where a 52-mile carriage ride through the country landed one David Walling of Greenwich NJ, who after arriving on ship had second thoughts, "stating that his family affairs would not let him!" An advance of two doubloons helped settle his misgivings. They were hit by several gales before they had cleared Cape May, and then "an anchor gunboat No. 16 or a 'Tommy Jefferson' boarded us and said, he believed we might proceed."

The ship's unnamed captain is presented as a surly incompetent, with navigation being a particular weakness; he blames a faulty calibration of the compass on page 11. The crew often sighted land and then needed to ask passing ships where they were. The lack of a spyglass on the ship is also noted on page 9. Treacherous shoals were narrowly averted. As they fumbled up the New England coast, the captain "concluded our chart must be bad, or that the currents were so variable it was impossible to calculate for them" (page 12). The narrator and his friend Le Gros sometimes stayed up an extra watch at night to be sure the ship would not be dashed to pieces.

The ship's first stop was, improbably, at the mouth of the remote Pleasant River in Maine, not far from the Canadian border. This is not described as a smuggling operation, but given the extreme secrecy, remote location, strict embargo regulations then in effect, and absence of customs officials, it certainly sounds like one. Our narrator and the captain "saw the father of the person we were in quest of having returned on board our vessel." Our narrator was sent on a rowboat 6 miles up river, and then "footing it first up and then down hill, now on all fours, and now up to my knees in mud, and now breaking my shins against the stones in the road." In rural Columbia, Maine he arranged the business and returned to his ship, which was anchored amid the rocks: "We were afterwards informed it was a great wonder we had not been dashed to pieces, having gone between many little islands where vessels never were before." The ship unloaded ballast and took on barrels of cargo.

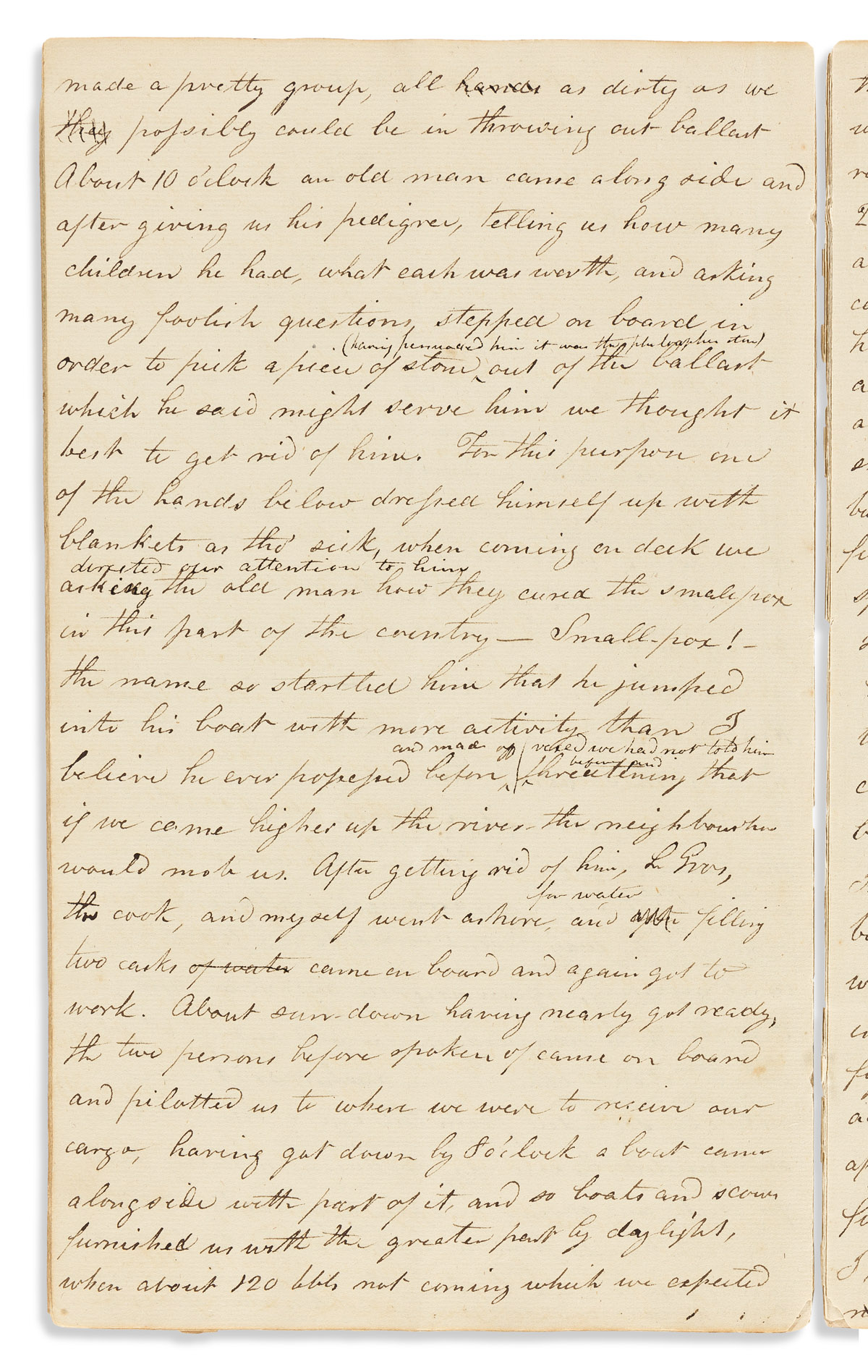

The loading of the vessel was interrupted by an old local man "giving us his pedigree . . . and asking many foolish questions." If there's one thing smugglers don't like, it's interlopers asking foolish questions. They devised a clever way to be rid of the nuisance: "One of the hands below dressed himself up with blankets as though sick. When coming on deck we directed our attention to him, asking the old man how they cured the smallpox in this part of the country. Small pox! The name so startled him that he jumped into his boat with more activity than I believe he ever possessed before." They loaded their barrels of cargo mostly by night in this desolate cove, with their local contact warning them about a dispatch boat which patrolled the coast. The promised warning shots failed to alert them when the dispatch boat made its appearance. "In close chase of us, we spread all our canvass with a fine breeze and soon left her behind . . . she soon turned about and bore up for two other vessels." Free of his late-night watches, his muddy slog to Columbia, and the successful escape from the authorities, our narrator then had "an opportunity for rest, I not having had sleep for three days and nights." This takes us through 31 August.

The ship then bore south toward the Caribbean with its mysterious cargo. The ship was inadequately provisioned, "without any liquor on board, our sugar and small stores lasting about half the passage when we substituted for coffee burnt biscuit boiled in water, having nothing but flour, biscuit and beef . . . we caught a barrel of rain water once in a heavy shower." The captain grew more surly and erratic: "When I went on deck I found him stretched his full length under the tiller with a rest provided by way of a pillow. I took the helm and remained at it 30 minutes before he awoke, when a quarrel immediately ensued in which he abused me much, [and] challenged Mr. Le Gros on the main deck to fight him." The captain shared a story from his time in charge of a legitimate mercantile voyage aboard the schooner Ann Pennock, in which he had broken open the barrels of flour, skimmed a small portion from each, and making himself up three new barrels of flour which he was able to sell on his own account. He proposed doing the same with his present cargo.

The ship arrived on the coast of Suriname (then a British colony) on 14 October to discharge their cargo, but "there being no chart on board which laid down the coast on soundings, the capt could not tell where we were, but one moment would say we were far to leeward of our port, and next a great way to windward." The captain led them into a (wrong) port, running onto shoals in sight of a British fort. The fort's commandant offered cursory aid, but lacked the boats to make a full rescue and also noted that the ship was likely to be marauded by a nearby French fort. The ship was miraculously able to detach from the rocks at high tide, and made its way to Bram's Point [Braamspunt], opposite the city of Paramaribo. "Here we lay all night, the crew keeping watch as it was feared our cables might break, but when it came to the captain's turn he laid down on the hen coop and went fast to sleep, leaving the vessel to the mercy of the waves." Here the narrator secured permission to trade from the colonial governor, and set about selling his cargo. He found that the crew was selling barrels off the ship behind his back, and when confronted, all including the captain threatened to quit. At this point, the first mate Rogers had harsh words with the narrator's friend Le Gros, and "threatened the owners and myself very hard, and I believe very little would have induced him and his companions to have risen on us, one of them having at all times a pistol, the only fire-arm on board." Our narrator was in charge of the ship's ownership papers, which the captain began asking to take possession of: "We were so much alarmed that we could not go to sleep both at a time."

The ship passed Tobago, Grenada, and Haiti. At the eastern tip of Jamaica they were boarded by the HMS Haddock, whose commander demanded to see the supercargo and his papers. Our nervous narrator went aboard and was told his papers were "all my eye Betty Martin." That is old English slang for "complete nonsense." The commander, who "in his dress resembled a Frenchman with a monkey roundabout," subjected him to "a great deal of cross-questioning and insolent language, telling me if I was worth it, he would send me in a prize." They impressed one sailor, "for whom I begged very hard, but to no purpose, and indeed twas with difficulty I got the other though he had a protection [certificate], the poor fellow being so frightened, could say nothing clear." The ship proceeded on to Kingston, Jamaica "in distress with 3 feet of water in our hold." At that point our narrator and Le Gros parted ways from the ship and booked their passage home on a British ship. They arrived in New York on 16 December and arrived in Philadelphia by stage four days later, "highly gratified at finding my relations and friends all well."

The last 4 pages of the narrative are devoted to a separate voyage: "After being here a few days it was concluded I should again go to sea, and on the 2nd Jan'y 1809 went on board the Ann Pennock cleared for Charleston." That was the same ship which his insane ex-captain had once defrauded, if you are paying close attention. This ship made it as far as Savannah, where they broke up upon the breakers trying to enter the harbor: "It was concluded the capt, his wife, and myself with 2 hands should make our escape and send the boat back for the others. We left the vessell with our trunks and in an hour and a half reached the shore. . . . We luckily had loaded pistols with us, by which we struck fire and so protected ourselves from the night air, we being on a desolate island with nothing to eat. . . . Fell in with a negro in a canoe. I went on board the canoe and after paddling several miles with him, got out of his canoe and footed it till sundown, when we arrived at a plantation, the property of Judge Stevens. . . . Next morn I crossed the ferry, at 12 o'clock arrived in Savanna, my feet all blisters." The Ann Pennock was towed into port for repairs on 17 March. In closing our narrator notes that "it was expected the city would be set on fire, many attempts having been made, but all nipped in the bud."

The author of this narrative has not been identified. He has provided enough circumstantial clues that an identification may not be impossible. On the other hand, he clearly took pains to avoid naming himself, his captain, his ship, and his cargo--likely because the entire voyage was of dubious legality. Why write the narrative, then? It appears to have been reworked and expanded from notes kept aboard the ship, with extensive revisions to improve the language and add details. One suspects he intended to publish it as a colorful maritime narrative, though we can find no hint that it ever made it to press. It's not too late.

The journal begins with our narrator shipping out from Philadelphia, and getting involved in an elaborate hunt for one more crew member. One man having fallen ill in Philadelphia, they failed to find a replacement in New Castle, DE, and went across the river to New Jersey, where a 52-mile carriage ride through the country landed one David Walling of Greenwich NJ, who after arriving on ship had second thoughts, "stating that his family affairs would not let him!" An advance of two doubloons helped settle his misgivings. They were hit by several gales before they had cleared Cape May, and then "an anchor gunboat No. 16 or a 'Tommy Jefferson' boarded us and said, he believed we might proceed."

The ship's unnamed captain is presented as a surly incompetent, with navigation being a particular weakness; he blames a faulty calibration of the compass on page 11. The crew often sighted land and then needed to ask passing ships where they were. The lack of a spyglass on the ship is also noted on page 9. Treacherous shoals were narrowly averted. As they fumbled up the New England coast, the captain "concluded our chart must be bad, or that the currents were so variable it was impossible to calculate for them" (page 12). The narrator and his friend Le Gros sometimes stayed up an extra watch at night to be sure the ship would not be dashed to pieces.

The ship's first stop was, improbably, at the mouth of the remote Pleasant River in Maine, not far from the Canadian border. This is not described as a smuggling operation, but given the extreme secrecy, remote location, strict embargo regulations then in effect, and absence of customs officials, it certainly sounds like one. Our narrator and the captain "saw the father of the person we were in quest of having returned on board our vessel." Our narrator was sent on a rowboat 6 miles up river, and then "footing it first up and then down hill, now on all fours, and now up to my knees in mud, and now breaking my shins against the stones in the road." In rural Columbia, Maine he arranged the business and returned to his ship, which was anchored amid the rocks: "We were afterwards informed it was a great wonder we had not been dashed to pieces, having gone between many little islands where vessels never were before." The ship unloaded ballast and took on barrels of cargo.

The loading of the vessel was interrupted by an old local man "giving us his pedigree . . . and asking many foolish questions." If there's one thing smugglers don't like, it's interlopers asking foolish questions. They devised a clever way to be rid of the nuisance: "One of the hands below dressed himself up with blankets as though sick. When coming on deck we directed our attention to him, asking the old man how they cured the smallpox in this part of the country. Small pox! The name so startled him that he jumped into his boat with more activity than I believe he ever possessed before." They loaded their barrels of cargo mostly by night in this desolate cove, with their local contact warning them about a dispatch boat which patrolled the coast. The promised warning shots failed to alert them when the dispatch boat made its appearance. "In close chase of us, we spread all our canvass with a fine breeze and soon left her behind . . . she soon turned about and bore up for two other vessels." Free of his late-night watches, his muddy slog to Columbia, and the successful escape from the authorities, our narrator then had "an opportunity for rest, I not having had sleep for three days and nights." This takes us through 31 August.

The ship then bore south toward the Caribbean with its mysterious cargo. The ship was inadequately provisioned, "without any liquor on board, our sugar and small stores lasting about half the passage when we substituted for coffee burnt biscuit boiled in water, having nothing but flour, biscuit and beef . . . we caught a barrel of rain water once in a heavy shower." The captain grew more surly and erratic: "When I went on deck I found him stretched his full length under the tiller with a rest provided by way of a pillow. I took the helm and remained at it 30 minutes before he awoke, when a quarrel immediately ensued in which he abused me much, [and] challenged Mr. Le Gros on the main deck to fight him." The captain shared a story from his time in charge of a legitimate mercantile voyage aboard the schooner Ann Pennock, in which he had broken open the barrels of flour, skimmed a small portion from each, and making himself up three new barrels of flour which he was able to sell on his own account. He proposed doing the same with his present cargo.

The ship arrived on the coast of Suriname (then a British colony) on 14 October to discharge their cargo, but "there being no chart on board which laid down the coast on soundings, the capt could not tell where we were, but one moment would say we were far to leeward of our port, and next a great way to windward." The captain led them into a (wrong) port, running onto shoals in sight of a British fort. The fort's commandant offered cursory aid, but lacked the boats to make a full rescue and also noted that the ship was likely to be marauded by a nearby French fort. The ship was miraculously able to detach from the rocks at high tide, and made its way to Bram's Point [Braamspunt], opposite the city of Paramaribo. "Here we lay all night, the crew keeping watch as it was feared our cables might break, but when it came to the captain's turn he laid down on the hen coop and went fast to sleep, leaving the vessel to the mercy of the waves." Here the narrator secured permission to trade from the colonial governor, and set about selling his cargo. He found that the crew was selling barrels off the ship behind his back, and when confronted, all including the captain threatened to quit. At this point, the first mate Rogers had harsh words with the narrator's friend Le Gros, and "threatened the owners and myself very hard, and I believe very little would have induced him and his companions to have risen on us, one of them having at all times a pistol, the only fire-arm on board." Our narrator was in charge of the ship's ownership papers, which the captain began asking to take possession of: "We were so much alarmed that we could not go to sleep both at a time."

The ship passed Tobago, Grenada, and Haiti. At the eastern tip of Jamaica they were boarded by the HMS Haddock, whose commander demanded to see the supercargo and his papers. Our nervous narrator went aboard and was told his papers were "all my eye Betty Martin." That is old English slang for "complete nonsense." The commander, who "in his dress resembled a Frenchman with a monkey roundabout," subjected him to "a great deal of cross-questioning and insolent language, telling me if I was worth it, he would send me in a prize." They impressed one sailor, "for whom I begged very hard, but to no purpose, and indeed twas with difficulty I got the other though he had a protection [certificate], the poor fellow being so frightened, could say nothing clear." The ship proceeded on to Kingston, Jamaica "in distress with 3 feet of water in our hold." At that point our narrator and Le Gros parted ways from the ship and booked their passage home on a British ship. They arrived in New York on 16 December and arrived in Philadelphia by stage four days later, "highly gratified at finding my relations and friends all well."

The last 4 pages of the narrative are devoted to a separate voyage: "After being here a few days it was concluded I should again go to sea, and on the 2nd Jan'y 1809 went on board the Ann Pennock cleared for Charleston." That was the same ship which his insane ex-captain had once defrauded, if you are paying close attention. This ship made it as far as Savannah, where they broke up upon the breakers trying to enter the harbor: "It was concluded the capt, his wife, and myself with 2 hands should make our escape and send the boat back for the others. We left the vessell with our trunks and in an hour and a half reached the shore. . . . We luckily had loaded pistols with us, by which we struck fire and so protected ourselves from the night air, we being on a desolate island with nothing to eat. . . . Fell in with a negro in a canoe. I went on board the canoe and after paddling several miles with him, got out of his canoe and footed it till sundown, when we arrived at a plantation, the property of Judge Stevens. . . . Next morn I crossed the ferry, at 12 o'clock arrived in Savanna, my feet all blisters." The Ann Pennock was towed into port for repairs on 17 March. In closing our narrator notes that "it was expected the city would be set on fire, many attempts having been made, but all nipped in the bud."

The author of this narrative has not been identified. He has provided enough circumstantial clues that an identification may not be impossible. On the other hand, he clearly took pains to avoid naming himself, his captain, his ship, and his cargo--likely because the entire voyage was of dubious legality. Why write the narrative, then? It appears to have been reworked and expanded from notes kept aboard the ship, with extensive revisions to improve the language and add details. One suspects he intended to publish it as a colorful maritime narrative, though we can find no hint that it ever made it to press. It's not too late.

Exhibition Hours

Exhibition Hours

Aliquam vulputate ornare congue. Vestibulum maximus, libero in placerat faucibus, risus nisl molestie massa, ut maximus metus lectus vel lorem.