Sale 2663 - Lot 296

Price Realized: $ 8,500

Price Realized: $ 10,625

?Final Price Realized includes Buyer’s Premium added to Hammer Price

Estimate: $ 10,000 - $ 15,000

(MILITARY--CIVIL WAR.) Eloquent letters of an officer of Colored Troops, one describing "the death hour of the rebellion" at Appomattox. 4 Autograph Letters Signed by Lieutenant George G. Smith to cousins Lydia and Mary Gardiner of West Chester, PA (each with a typed transcript), one photograph in uniform, sleeved in two binders with additional papers. Various places, 1864-1865

Additional Details

"Every musket was pointed toward the sky, and a perfect roar swept from right to left as all the pieces were discharged in the air. . . . Soldiers struck up 'Glory, Glory, Hallelujah.'"

These unusually eloquent letters were written by a white lieutenant in the 29th United States Colored Troops, with reference to the Fort Pillow massacre, the fall of Petersburg, Lee's surrender at Appomattox, the right to suffrage, the occupation of Texas, and more.

The first letter was written on 10 and 19 December 1864, shortly after all of the regiments of Colored Troops in the Army of the James had been consolidated together into the XXV Corps. The regiment was encamped at Point of Rocks on the Appomattox River in Virginia, where the rebel pickets were close enough to banter with Union troops: "One day this week, I received three Rebel deserters into our lines. . . . They considered the South already whipped. These are, I am told, the first Johnnies who have ventured to desert to us since the Colored Division came to this line. They seemed glad to see me, as if they distrusted the Black boys, and thought it possible they might remember Fort Pillow. . . . Some of our men are wounded nearly every day now on the picket line. A sharpshooter had a sincere desire to pick me off yesterday, but just missed me, thanks to a higher power."

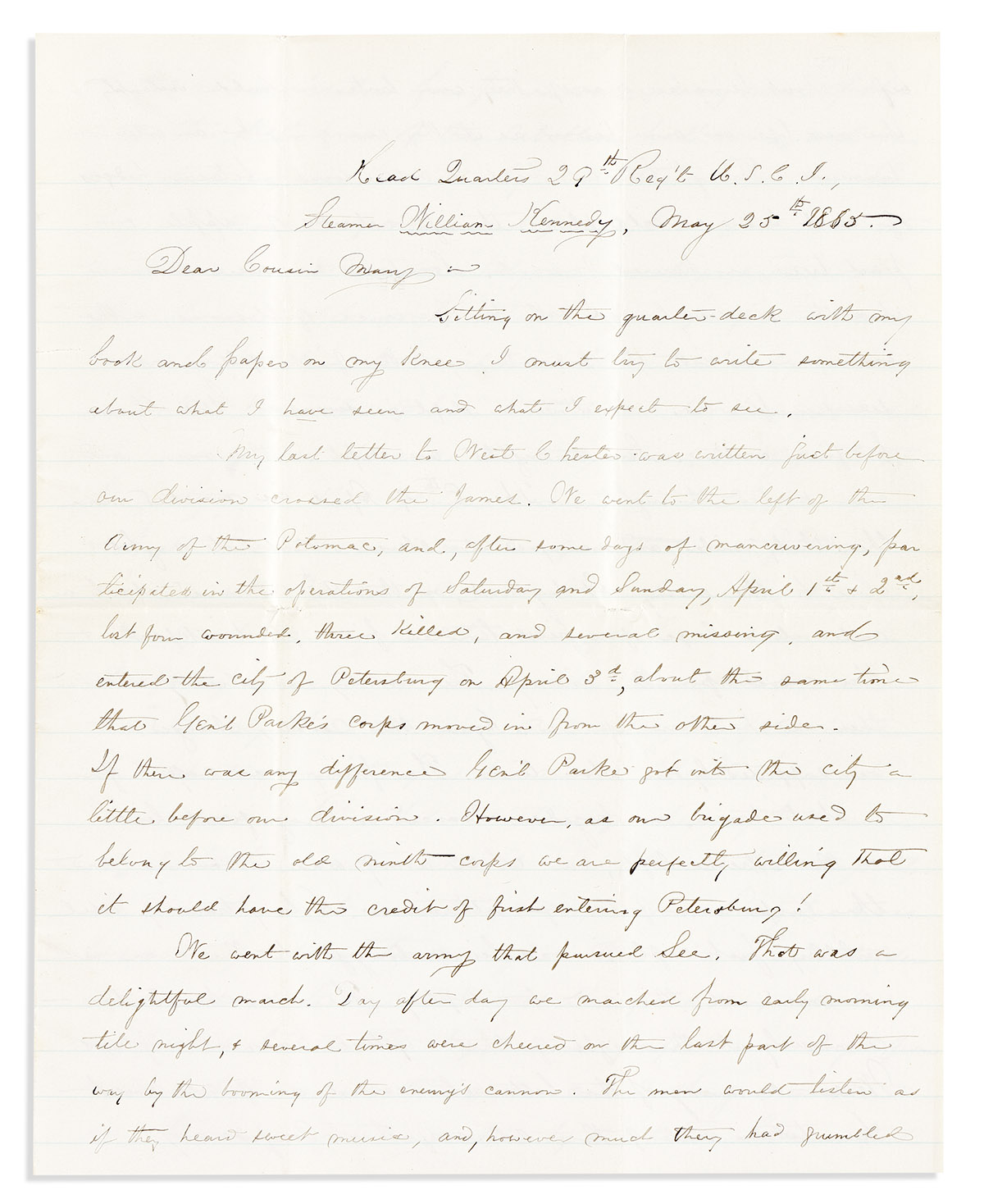

Smith's 25 May 1865 letter describes the exuberant final days of fighting. The regiment "entered the city of Petersburg on April 3d, about the same time that Gen'l Parke's Corps moved in from the other side. . . . We went with the Army that pursued Lee. That was a delightful march. Day after day we marched from early morning till night, & several times were cheered on the last part of the way by the booming of the enemy's cannon. The men would listen as if they heard sweet music, and however much they had grumbled before about being 'raced as if they were brutes,' would instantly show new life and move forward as if they were going to an entertainment. Through beautiful fields & noble woods, between hedges of sweet briar & wild plum, through orchards of apple & peach trees, we hurried forward." He describes the 9 April Battle of Appomattox Court House which led to Lee's surrender: "The cavalry charged & was supported by our whole line. The firing was rapid for a short time, our brigade advanced in magnificent line on the extreme left, our whole army was advancing, and the troops were full of enthusiasm. . . . The men cheered at the sight of the captured cannons & flags. We saw so many of the latter, it seemed as if we must have taken most of the colors of the Confederacy. We had nerved ourselves for fierce work, every man felt as if the death hour of the rebellion had come, and we were glad we were honored by being there. . . . We moved in line of battle over fields carpeted with violets, with orders to continue thus to advance till we should engage the enemy. As we drew nearer the firing ceased. No more shells came howling over us. Quickly there came an aid riding a fleet horse, and shouting something as he rode. 'Gen'l Lee has surrendered.' Oh what a storm of cheering! I never expect to hear another like it. . . . Then a sudden impulse seemed to seize the whole line, and every musket was pointed toward the sky, and a perfect roar swept from right to left as all the pieces were discharged in the air. Officers grabbed one another by the hand. Soldiers struck up 'Glory, Glory, Hallelujah.'"

This letter (and the next) were written shipboard as the regiment headed off to Texas to quell the last corner of the Confederacy. They landed at Galveston on 18 June 1865, where General Granger read the Juneteenth proclamation the following day (not described here).

Lieutenant Smith's final letter was written from Ringgold Barracks in occupied Texas, 13 September 1865. He describes "a sun so hot that almost every time the battalion is formed in it, someone drops to the ground overpowered and fainting. Too many have gone from the parade to the hospital, and from there to the grave. This might not have happened so frequently if the men had not been half dead with scurvy. . . . They suffer as deeply and patiently as white men." He also discusses "the advisability of allowing colored men the right of suffrage. It seems to me no one should be allowed to vote who cannot read, and all Americans, white or black, who can read, ought to be permitted to vote. . . . Oh, what a Black Republican I am! But I will not afflict you any more with my radical views. I like the Colored Service, Lydie. These men are certainly capable of becoming admirable soldiers. Many of them are such. More thorough discipline than prevails in our regiment cannot be found, I believe, in the Army." He also describes the Texas border region at length, including the methods which Mexican women use to milk a goat, and a society ball he attended across the border in Camargo, Mexico.

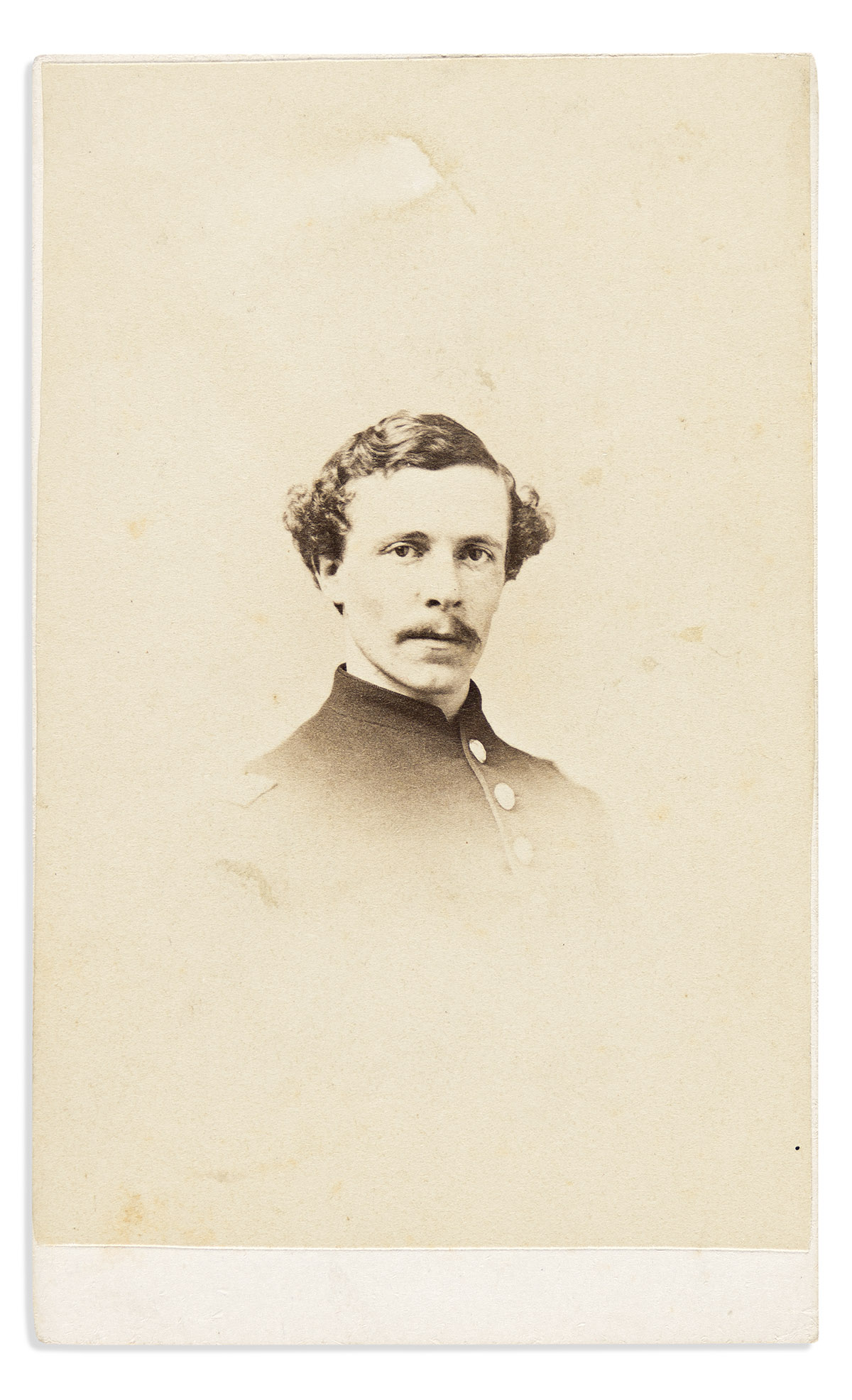

The author of these letters, George Gardiner Smith (1838-1919) came from a distinguished Pittsburgh family and attended Williams College in Massachusetts. He was studying for the ministry when he left school in 1863 and was drafted. He served as a second lieutenant of the 29th United States Colored Troops from October 1864 until the regiment was mustered out in November 1865. Also included in the lot are: 5 cartes de visite of Smith, one in his Civil War uniform; two diary leaves from 1857 and 1859; 8 letters written to various family members from 1862 to 1864 before he joined the service, one 1899 letter to his brother Luther; 6 manuscript essays from his Pittsburgh debating society; 10 letters addressed to Smith by college friends and others, 1857-1860.

These unusually eloquent letters were written by a white lieutenant in the 29th United States Colored Troops, with reference to the Fort Pillow massacre, the fall of Petersburg, Lee's surrender at Appomattox, the right to suffrage, the occupation of Texas, and more.

The first letter was written on 10 and 19 December 1864, shortly after all of the regiments of Colored Troops in the Army of the James had been consolidated together into the XXV Corps. The regiment was encamped at Point of Rocks on the Appomattox River in Virginia, where the rebel pickets were close enough to banter with Union troops: "One day this week, I received three Rebel deserters into our lines. . . . They considered the South already whipped. These are, I am told, the first Johnnies who have ventured to desert to us since the Colored Division came to this line. They seemed glad to see me, as if they distrusted the Black boys, and thought it possible they might remember Fort Pillow. . . . Some of our men are wounded nearly every day now on the picket line. A sharpshooter had a sincere desire to pick me off yesterday, but just missed me, thanks to a higher power."

Smith's 25 May 1865 letter describes the exuberant final days of fighting. The regiment "entered the city of Petersburg on April 3d, about the same time that Gen'l Parke's Corps moved in from the other side. . . . We went with the Army that pursued Lee. That was a delightful march. Day after day we marched from early morning till night, & several times were cheered on the last part of the way by the booming of the enemy's cannon. The men would listen as if they heard sweet music, and however much they had grumbled before about being 'raced as if they were brutes,' would instantly show new life and move forward as if they were going to an entertainment. Through beautiful fields & noble woods, between hedges of sweet briar & wild plum, through orchards of apple & peach trees, we hurried forward." He describes the 9 April Battle of Appomattox Court House which led to Lee's surrender: "The cavalry charged & was supported by our whole line. The firing was rapid for a short time, our brigade advanced in magnificent line on the extreme left, our whole army was advancing, and the troops were full of enthusiasm. . . . The men cheered at the sight of the captured cannons & flags. We saw so many of the latter, it seemed as if we must have taken most of the colors of the Confederacy. We had nerved ourselves for fierce work, every man felt as if the death hour of the rebellion had come, and we were glad we were honored by being there. . . . We moved in line of battle over fields carpeted with violets, with orders to continue thus to advance till we should engage the enemy. As we drew nearer the firing ceased. No more shells came howling over us. Quickly there came an aid riding a fleet horse, and shouting something as he rode. 'Gen'l Lee has surrendered.' Oh what a storm of cheering! I never expect to hear another like it. . . . Then a sudden impulse seemed to seize the whole line, and every musket was pointed toward the sky, and a perfect roar swept from right to left as all the pieces were discharged in the air. Officers grabbed one another by the hand. Soldiers struck up 'Glory, Glory, Hallelujah.'"

This letter (and the next) were written shipboard as the regiment headed off to Texas to quell the last corner of the Confederacy. They landed at Galveston on 18 June 1865, where General Granger read the Juneteenth proclamation the following day (not described here).

Lieutenant Smith's final letter was written from Ringgold Barracks in occupied Texas, 13 September 1865. He describes "a sun so hot that almost every time the battalion is formed in it, someone drops to the ground overpowered and fainting. Too many have gone from the parade to the hospital, and from there to the grave. This might not have happened so frequently if the men had not been half dead with scurvy. . . . They suffer as deeply and patiently as white men." He also discusses "the advisability of allowing colored men the right of suffrage. It seems to me no one should be allowed to vote who cannot read, and all Americans, white or black, who can read, ought to be permitted to vote. . . . Oh, what a Black Republican I am! But I will not afflict you any more with my radical views. I like the Colored Service, Lydie. These men are certainly capable of becoming admirable soldiers. Many of them are such. More thorough discipline than prevails in our regiment cannot be found, I believe, in the Army." He also describes the Texas border region at length, including the methods which Mexican women use to milk a goat, and a society ball he attended across the border in Camargo, Mexico.

The author of these letters, George Gardiner Smith (1838-1919) came from a distinguished Pittsburgh family and attended Williams College in Massachusetts. He was studying for the ministry when he left school in 1863 and was drafted. He served as a second lieutenant of the 29th United States Colored Troops from October 1864 until the regiment was mustered out in November 1865. Also included in the lot are: 5 cartes de visite of Smith, one in his Civil War uniform; two diary leaves from 1857 and 1859; 8 letters written to various family members from 1862 to 1864 before he joined the service, one 1899 letter to his brother Luther; 6 manuscript essays from his Pittsburgh debating society; 10 letters addressed to Smith by college friends and others, 1857-1860.

Exhibition Hours

Exhibition Hours

Aliquam vulputate ornare congue. Vestibulum maximus, libero in placerat faucibus, risus nisl molestie massa, ut maximus metus lectus vel lorem.