Sale 2631 - Lot 249

Price Realized: $ 11,500

Price Realized: $ 14,375

?Final Price Realized includes Buyer’s Premium added to Hammer Price

Estimate: $ 8,000 - $ 12,000

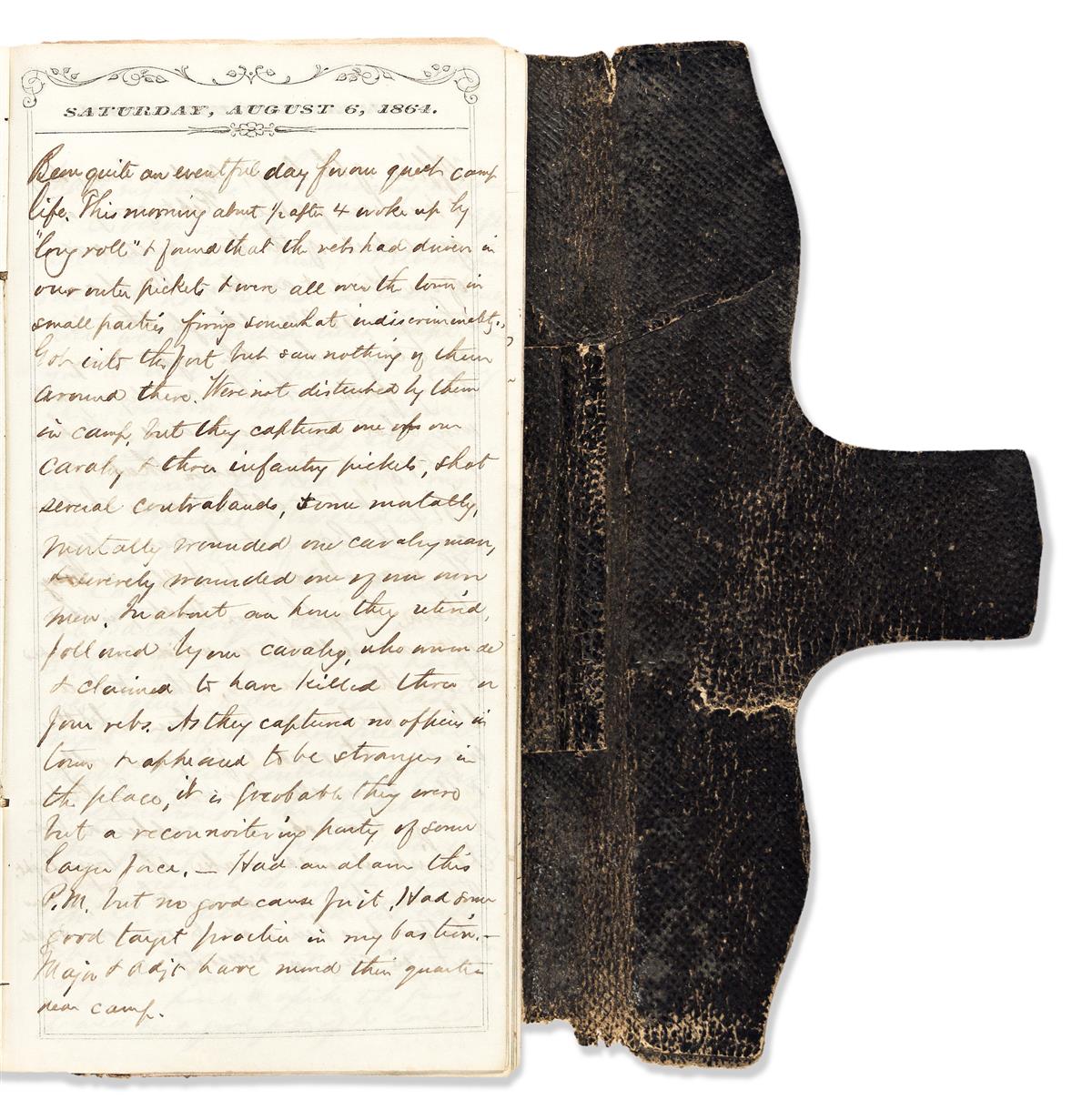

(MILITARY--CIVIL WAR.) Joshua M. Addeman. Detailed and observant diary by a captain in the 14th Rhode Island Heavy Artillery (Colored). [347] manuscript diary pages, plus 19 pages of memoranda. 12mo, original limp calf, moderate wear, front joint splitting; only two entries before 20 January, but nearly daily long entries after that, minor wear to contents, a few leaves coming detached. Various places, 1 January to 31 December 1864

Additional Details

This diary traces nearly a year in the life of a Black regiment in Louisiana, as seen by the captain of Company H. The diary is filled with well-drawn anecdotes which illustrate the life in camp, pleasant and otherwise.

The 14th Rhode Island Heavy Artillery (Colored) regiment was formed in August 1863 (the name was officially changed to the 11th United States Colored Heavy Artillery Regiment in May 1864). The white officers were all Rhode Islanders, but the enlisted men were recruited from all over the country. In this diary, Captain Addeman takes over command of Company H on 13 January: "I want to make the personal acquaintance of every man. Then I shall know how to take him." He made a continuous effort to select the best of his enlisted men and train them into effective corporals and sergeants: "If we can have a system by which the responsibility can be put upon the non-coms themselves, it will make much easier work." He made several efforts to establish schools for these non-commissioned officers, and was constantly promoting and demoting men to find the best use of his personnel. His soldiers had been promised substantial bounties, much of which were siphoned off by unscrupulous recruiting officers. The fight to have this money restored was a recurring theme.

Addeman was creative in the invention of cruel punishments for his men. On the ship ride southwards, "Found a thief, Wm George, in my co., and made him tramp the hurricane deck with a placard marked thief on his back" (29 January). More disturbingly, on 20 February "I adopted a novel punishment with one of my men. Having done his business in the river from which we draw our drinking and washing water, I put a board over his shoulders and some dung right under his nose, which he had the enjoyment of for two or three hours."

After a difficult ship passage southward, Company H arrived at English Turn, LA on 6 February, and then relocated to Plaquemine near Baton Rouge on 26 March. They remained there through the close of the war. Addeman was not sparing with his opinions of his men, and of his fellow officers. As with many regiments in the deep south, death from disease was a regular part of camp life, and Addeman had a disturbing habit of insulting soldiers who had just died. On 21 February, one private "died this morning of inflammation of the bowels, undoubtedly brought on by his own neglect & filthiness. Was even known in the co. as 'Nasty.'" On 25 June, after the sudden death of another private, he wrote: "This was one who could be spared. Filthy, rascally, perfidious, wasteful, he had hardly a single good trait. Most of the men I have lost by death were more or less of the same stamp." On 12 November he memorialized an older soldier "who so long 'played off' & at last made himself sick in reality, died last night. He has received the penalty of enlisting under false pretenses, representing himself ten years younger than he was, dyeing his hair &c." On the other hand, the deceased Private Francis Cummins "always did his duty faithfully" (22 April), and Private Joseph Henson who succumbed to malaria "was a very good man" (10 September).

On a lighter note, camp entertainments are noted at length. Washington's Birthday saw wheelbarrow and sack races, and chasing a greased pig. On 12 February Addeman noted: "The men have a rough kind of sport in striking each other with switches, which must wear out their clothes terribly, but which they seem to enjoy with good gusto." On Independence Day, "the non-coms have a dance down town. Great preparations for a big time, lots of muslin, flowers and dusky beauties there." The company musicians were quite accomplished, and Private Edward St. Clair was a born entertainer who is mentioned several times: On 17 March St. Clair "made a great deal of sport by his exhibition of two fellows so rigged up as to represent an elephant. He can imitate the showman to perfection. He is smart and a brimful of fun and mischief. I hardly know what to make of him." St. Clair was later court-martialed and sent to the Union prison in the Dry Tortugas.

Like many of the Black regiments, the 14th Rhode Island did not see much heavy combat. However, they were stationed near the action, in an area crawling with all varieties of guerrillas, raiding parties, and rebel sympathizers. On 28 June, "two of our cavalry pickets were captured this forenoon by two Confederates under the most humiliating circumstances. They were sitting by the roadside reading a paper with their carbines the other side of the fence & their horses some distance off. The Confed dashed upon them and gobbled them. The worst of it is their captors were mere boys of some 16 or 17, belonging here." The worst clash was on 6 August, with a force of a hundred Texan guerrilla scouts under 20-year-old Leander McNelly: "This morning about 1/2 after 4, woke up by the long roll & found that the rebs had driven in our outer pickets & were all over the town in small parties, firing somewhat indiscriminately. . . . They captured one of our cavalry & three infantry pickets, shot several contrabands, some mortally, mortally wounded one cavalryman, severely wounded one of our own men." Black troops captured by the Confederates never fared well. The next day, Addeman learned that "our inf'y pickets captured were shot across the bayou at Indian Village. The man who says he helped to bury them brings the news. His story is that after a consultation in which some wanted to use them as servants, others to kill them, twelve men took them a little way down the road & firing one volley killed them all."

On several occasions, Addeman records his conversations with formerly enslaved people. On 17 February, on the nearby Villiers plantation, "we called on an old col'd woman who is too old to receive wages & has to do outside work for her living. She is however very smart to all appearances, & very interesting to talk with. Gives some striking pictures of the beauties of slavery as it was. Asked her if the people were any better off than they used to be. 'Oh," she says, 'don't mention it. Ten thousand times.' . . . She had seen the poor creatures flogged till the ground was covered in their blood. It has seen its day, and this tyranny will soon be over." On 22 April, "An old darkey called on me this afternoon with a bunch of roses & I had quite a chat with him about the people & country here. From his story, bad enough as the Negroes may be, it is infinitely better than under secesh rule."

The diary's author Joshua Melancthon Addeman (1840-1930) of Providence, RI was born in New Zealand to white parents from England. They emigrated to America when he was a young boy. He graduated from Brown University in 1862. He was, we believe, the only Union officer born in New Zealand. Addeman returned to Providence, RI after the war and practiced law; he served as Secretary of State of Rhode Island from 1872 to 1887. In 1880, he published a short memoir, "Reminiscences of Two Years with the Colored Troops." This diary is written with a great deal more frankness than the published memoir, and is one of the more revealing accounts we have seen of life in a Black regiment. Further notes are available upon request.

The 14th Rhode Island Heavy Artillery (Colored) regiment was formed in August 1863 (the name was officially changed to the 11th United States Colored Heavy Artillery Regiment in May 1864). The white officers were all Rhode Islanders, but the enlisted men were recruited from all over the country. In this diary, Captain Addeman takes over command of Company H on 13 January: "I want to make the personal acquaintance of every man. Then I shall know how to take him." He made a continuous effort to select the best of his enlisted men and train them into effective corporals and sergeants: "If we can have a system by which the responsibility can be put upon the non-coms themselves, it will make much easier work." He made several efforts to establish schools for these non-commissioned officers, and was constantly promoting and demoting men to find the best use of his personnel. His soldiers had been promised substantial bounties, much of which were siphoned off by unscrupulous recruiting officers. The fight to have this money restored was a recurring theme.

Addeman was creative in the invention of cruel punishments for his men. On the ship ride southwards, "Found a thief, Wm George, in my co., and made him tramp the hurricane deck with a placard marked thief on his back" (29 January). More disturbingly, on 20 February "I adopted a novel punishment with one of my men. Having done his business in the river from which we draw our drinking and washing water, I put a board over his shoulders and some dung right under his nose, which he had the enjoyment of for two or three hours."

After a difficult ship passage southward, Company H arrived at English Turn, LA on 6 February, and then relocated to Plaquemine near Baton Rouge on 26 March. They remained there through the close of the war. Addeman was not sparing with his opinions of his men, and of his fellow officers. As with many regiments in the deep south, death from disease was a regular part of camp life, and Addeman had a disturbing habit of insulting soldiers who had just died. On 21 February, one private "died this morning of inflammation of the bowels, undoubtedly brought on by his own neglect & filthiness. Was even known in the co. as 'Nasty.'" On 25 June, after the sudden death of another private, he wrote: "This was one who could be spared. Filthy, rascally, perfidious, wasteful, he had hardly a single good trait. Most of the men I have lost by death were more or less of the same stamp." On 12 November he memorialized an older soldier "who so long 'played off' & at last made himself sick in reality, died last night. He has received the penalty of enlisting under false pretenses, representing himself ten years younger than he was, dyeing his hair &c." On the other hand, the deceased Private Francis Cummins "always did his duty faithfully" (22 April), and Private Joseph Henson who succumbed to malaria "was a very good man" (10 September).

On a lighter note, camp entertainments are noted at length. Washington's Birthday saw wheelbarrow and sack races, and chasing a greased pig. On 12 February Addeman noted: "The men have a rough kind of sport in striking each other with switches, which must wear out their clothes terribly, but which they seem to enjoy with good gusto." On Independence Day, "the non-coms have a dance down town. Great preparations for a big time, lots of muslin, flowers and dusky beauties there." The company musicians were quite accomplished, and Private Edward St. Clair was a born entertainer who is mentioned several times: On 17 March St. Clair "made a great deal of sport by his exhibition of two fellows so rigged up as to represent an elephant. He can imitate the showman to perfection. He is smart and a brimful of fun and mischief. I hardly know what to make of him." St. Clair was later court-martialed and sent to the Union prison in the Dry Tortugas.

Like many of the Black regiments, the 14th Rhode Island did not see much heavy combat. However, they were stationed near the action, in an area crawling with all varieties of guerrillas, raiding parties, and rebel sympathizers. On 28 June, "two of our cavalry pickets were captured this forenoon by two Confederates under the most humiliating circumstances. They were sitting by the roadside reading a paper with their carbines the other side of the fence & their horses some distance off. The Confed dashed upon them and gobbled them. The worst of it is their captors were mere boys of some 16 or 17, belonging here." The worst clash was on 6 August, with a force of a hundred Texan guerrilla scouts under 20-year-old Leander McNelly: "This morning about 1/2 after 4, woke up by the long roll & found that the rebs had driven in our outer pickets & were all over the town in small parties, firing somewhat indiscriminately. . . . They captured one of our cavalry & three infantry pickets, shot several contrabands, some mortally, mortally wounded one cavalryman, severely wounded one of our own men." Black troops captured by the Confederates never fared well. The next day, Addeman learned that "our inf'y pickets captured were shot across the bayou at Indian Village. The man who says he helped to bury them brings the news. His story is that after a consultation in which some wanted to use them as servants, others to kill them, twelve men took them a little way down the road & firing one volley killed them all."

On several occasions, Addeman records his conversations with formerly enslaved people. On 17 February, on the nearby Villiers plantation, "we called on an old col'd woman who is too old to receive wages & has to do outside work for her living. She is however very smart to all appearances, & very interesting to talk with. Gives some striking pictures of the beauties of slavery as it was. Asked her if the people were any better off than they used to be. 'Oh," she says, 'don't mention it. Ten thousand times.' . . . She had seen the poor creatures flogged till the ground was covered in their blood. It has seen its day, and this tyranny will soon be over." On 22 April, "An old darkey called on me this afternoon with a bunch of roses & I had quite a chat with him about the people & country here. From his story, bad enough as the Negroes may be, it is infinitely better than under secesh rule."

The diary's author Joshua Melancthon Addeman (1840-1930) of Providence, RI was born in New Zealand to white parents from England. They emigrated to America when he was a young boy. He graduated from Brown University in 1862. He was, we believe, the only Union officer born in New Zealand. Addeman returned to Providence, RI after the war and practiced law; he served as Secretary of State of Rhode Island from 1872 to 1887. In 1880, he published a short memoir, "Reminiscences of Two Years with the Colored Troops." This diary is written with a great deal more frankness than the published memoir, and is one of the more revealing accounts we have seen of life in a Black regiment. Further notes are available upon request.

Exhibition Hours

Exhibition Hours

Aliquam vulputate ornare congue. Vestibulum maximus, libero in placerat faucibus, risus nisl molestie massa, ut maximus metus lectus vel lorem.