Sale 2663 - Lot 298

Price Realized: $ 11,000

Price Realized: $ 13,750

?Final Price Realized includes Buyer’s Premium added to Hammer Price

Estimate: $ 12,000 - $ 18,000

(MILITARY--CIVIL WAR.) Large archive of personal and official papers of a lieutenant with the 22nd United States Colored Troops. More than 400 items (0.7 linear feet) in one box; condition varies but generally minor wear. Various places, 1849-1904

Additional Details

"Yesterday the President & Gen. Grant came up to see the boys."

William Delville Milliken (1837-1887) of Albion, NY enlisted as a private in the all-white 4th New York Heavy Artillery in August 1862. In December 1863, he became a lieutenant in the 22nd United States Colored Troops, a regiment composed largely of Black recruits from New Jersey.

This lot includes 28 letters home which Milliken wrote as a lieutenant with the Colored Troops. The first three are written from basic training at Camp William Penn, the best known training base for the new Black regiments. On 7 January 1864 he wrote: "When I came here the men of my Co. did not know the first thing about drill, but you would be surprised to see how fast they learn. . . . I have seen many white troops with more drill do worse." On 16 January, he wrote "Lt. Heiner & myself went to town (Phil.) yesterday to see if we could not find out in what manner or who the parties were that swindled the Black men out of their bounty for so much." On 28 January, he expressed a wish to make "a few of those miserable sneaking Copperheads . . . drill with the Negroes a few days. How I do despise such traitors. . . . I wish you could be here to see the colored population come to camp to see their friends. It is gay, I assure you."

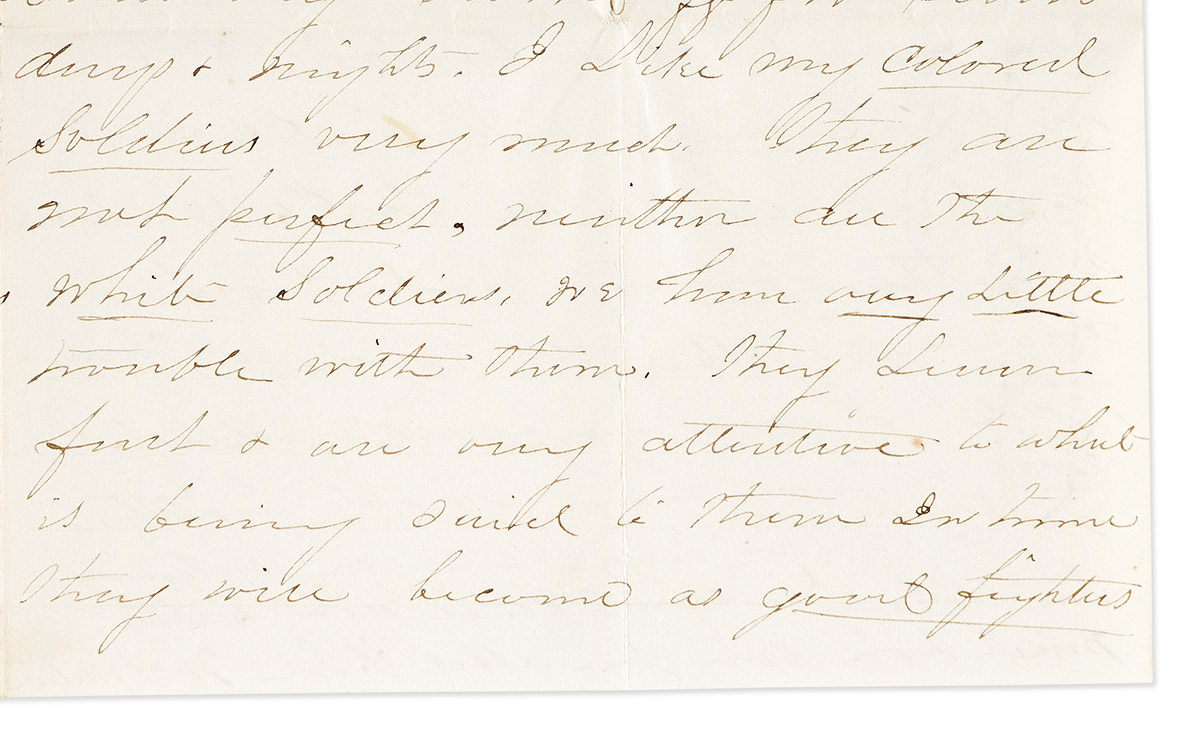

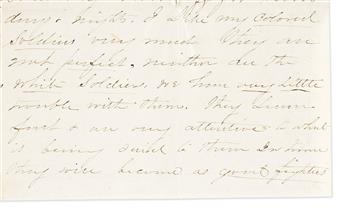

After the regiment deployed to Yorktown, VA, Milliken wrote a letter to his grandmother: "I like my colored soldiers very much. They are not perfect, neither are the white soldiers. We have very little trouble with them. They learn fast & are very attentive to what is being said to them. In time they will become as good fighters as the white boys" (7 April).

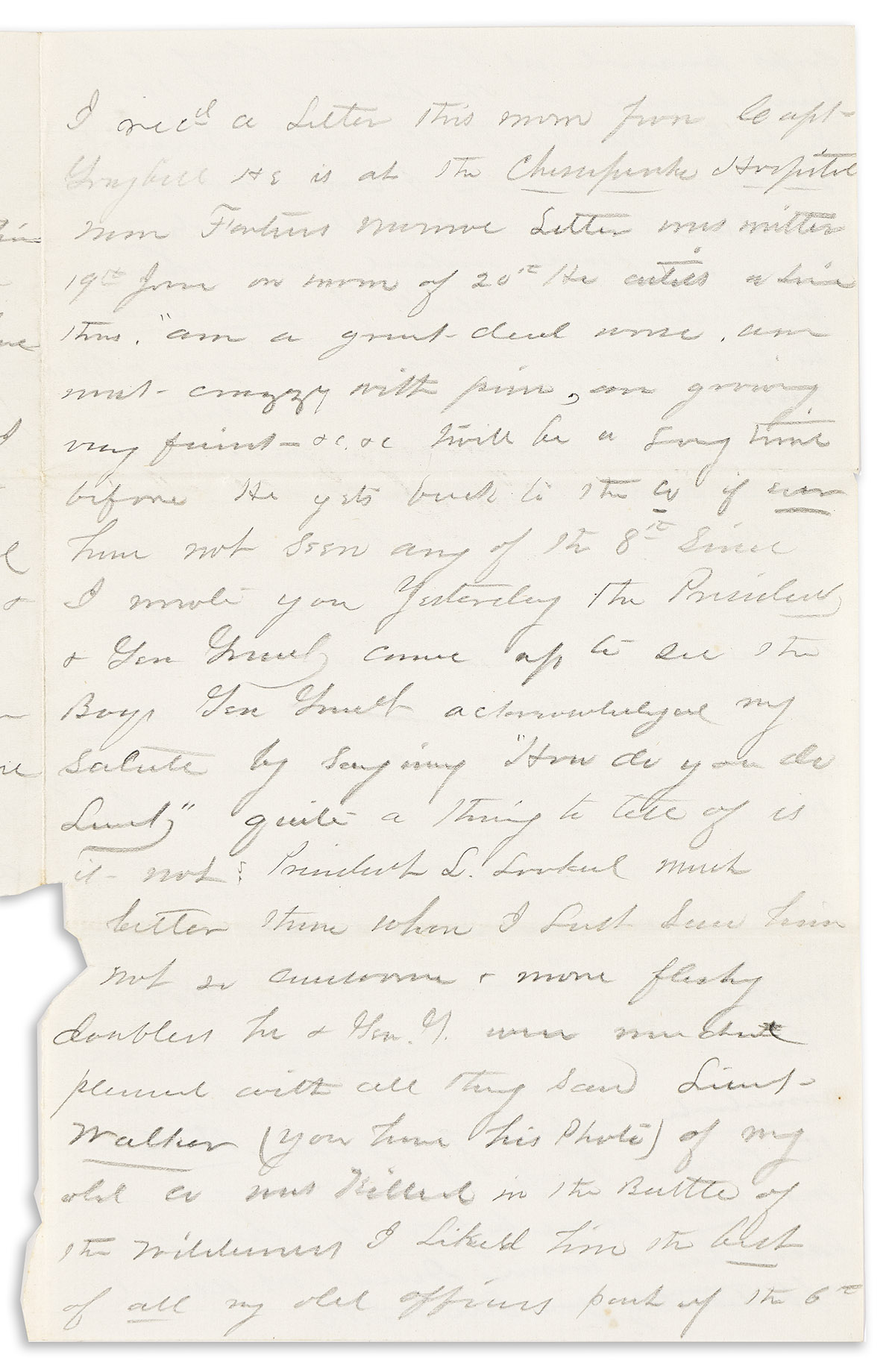

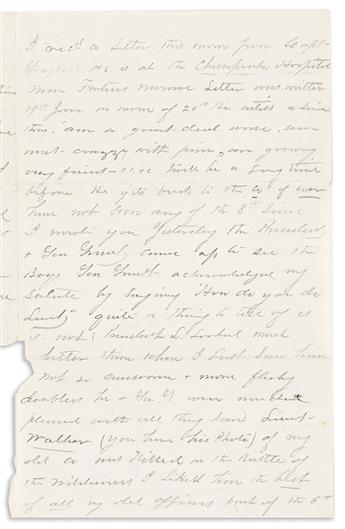

As the regiment settled in for the Siege of Petersburg, Milliken described his personal servant on 22 June: "I have one of the best of boys for a servant, carried all my things on a march & looks out generally for my uniform & comfort, cooks, & in fact is handy at anything. . . . Yesterday the President & Gen'l Grant came up to see the boys. Gen. Grant acknowledged by salute by saying 'How do you do, lieut.' . . . Pres. Lincoln looked much better than when I last seen him . . . more fleshy. Doubtless he & Gen. G. were pleased with all they saw."

Five days later, the regiment was under heavy fire: "A battery was erected immediately in front of our reg't. As soon as morning broke & discovered the fact to the Rebs, they opened a most terrible fire on said battery, & of course we suffered as much as the B. For an hour, a perfect shower of shot & shell rained upon us, but fortunately only 6 men in the whole reg't were hit. . . . The sharpshooters of the Rebs take great delight in shooting at Negroes." A partial letter written just after the 30 July Battle of the Crater reports that "our reg't lost during the day probably 6 or 8 killed & wounded."

22 November found Milliken detailed to the regimental headquarters, where he described the Black office staff: "Two drummer boys (which we keep here at headq'rs for orderlies) are dozeing off at my left. On my right is my table, & at it sit the serg't major & a clerk making out a list of absentees." He was miffed that a hometown acquaintance had not visited while in the area: "Perhaps he felt ashamed to let anyone know he had an acquaintance in a Col'd Reg't. If he was, I am very very glad I did not see him. Mrs. Reed only shows her ignorance when she talks as she does about col'd troops." Milliken notes that General Butler recently called the 22nd "the best Col'd Reg't in the U.S. service. . . . I doubt whether any white reg't in the Department stands higher in his favor."

The regiment suffered heavy losses at the 27 October 1864 Battle of Fair Oaks, which was widely attributed to the drunken state of its commander Colonel Joseph Barr Kiddoo. Milliken discusses this allegation in his 27 November letter: "I am very sorry to say that I think Col. Kiddoo was a little tight on the day of our last fight. Several of us were so strongly impressed with that belief that we did apply for a court of inquiry. . . . Our reg't has had & earned a good name & to have it lost in this style is more than we care to bear." The next day, Milliken was one of six company officers who signed a formal accusation against his colonel, as published in the official records of the Union Army.

On 17 April 1865, two days after the assassination, Milliken told his father: "We start tonight for Washington to participate in the funeral exercises of President Lincoln (late). I feel it quite an honor, but a very sad one." On 20 May 1865, he wrote "What do you think of Jeff D now? How comical the ending of the Great Rebellion." The regiment spent the last months of the war in Brownsville, TX on the Mexican border. A manuscript copy of a 26 July 1865 order explains the use of aloe to avoid scurvy, ordering a detachment of one officer and 25 men to head into the wilderness with a guide to collect it.

20 earlier Civil War letters were written while Milliken was a private in the 4th New York Heavy Artillery, stationed in the defenses of Washington. The regiment was initially led by Colonel Thomas Donnelly Doubleday, brother of the well-known Abner Doubleday. Two of the letters are on illustrated regimental letterhead, one naming Doubleday as commander. On 14 September 1863 Milliken discusses his thoughts on a possible new venture: "I have thought a great deal of late about the Negro reg'ts. I believe there is the place for men to show their patriotism & as far as what the world & the rest of mankind would say, I do not care one fig for." He announces on 11 December that he passed the board of examiners and was commissioned a second lieutenant.

The 51 manuscript regimental and brigade reports in this lot include several listing soldier names. They include the muster-in roll of Company E dated 12 January 1864, listing the 100 members of the company with their age and home town. New Jersey and Delaware soldiers are predominant. A Company E clothing roll from August 1864 includes the signatures of 39 soldiers, almost all of them by mark. A statement of charges for the first quarter of 1864 lists 5 soldiers who are charged for losing gear, along with the circumstances of the loss. Another is a "List of men on duty at Headquarters" spanning from January to September 1865, listing 19 enlisted men and their duties at the headquarters as clerks, a nurse, an orderly, and several "Regimental Pioneers."

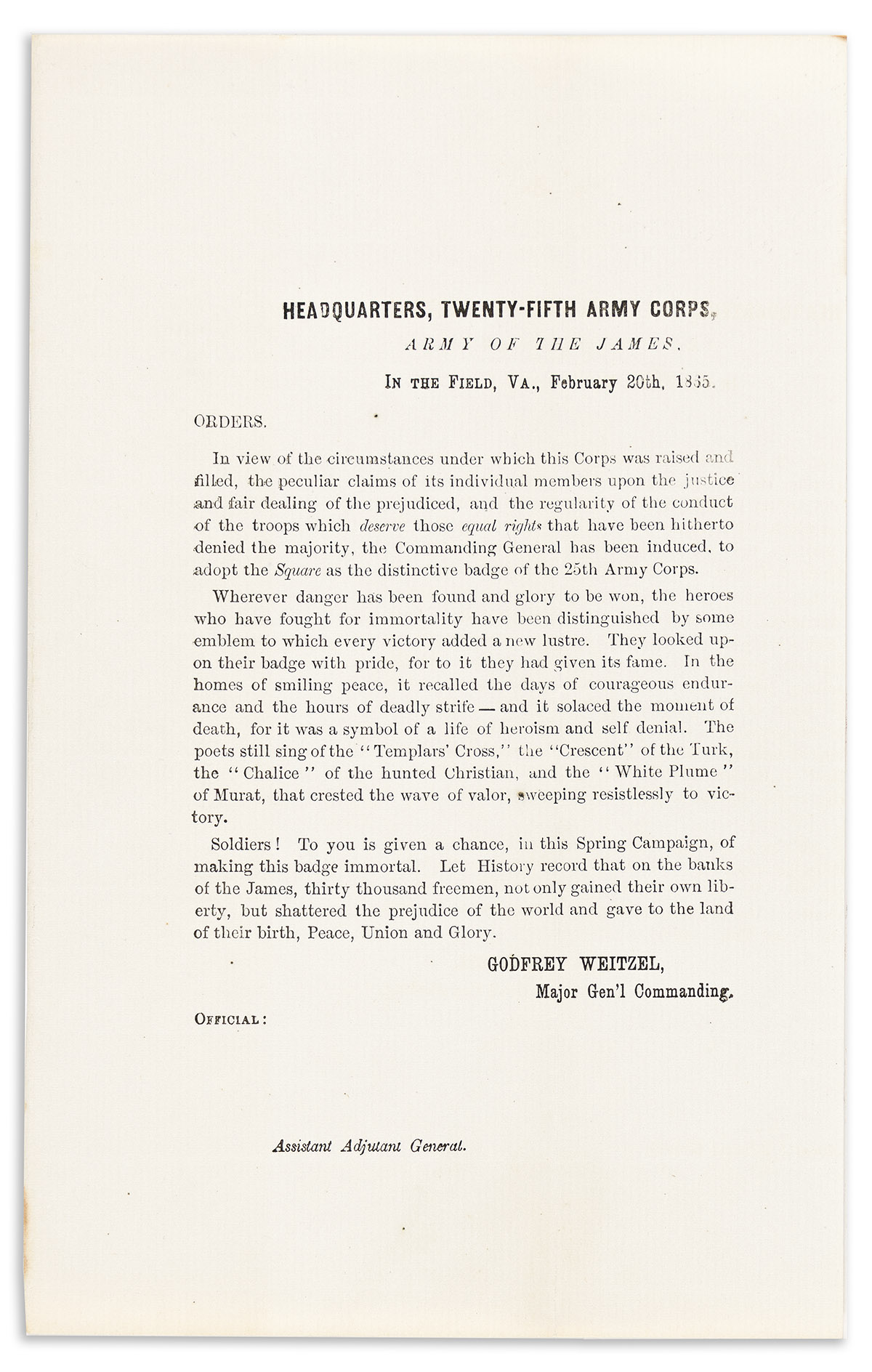

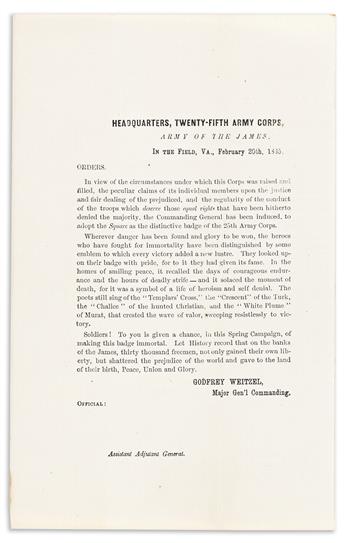

A thick sheaf of 115 official company and regimental letters and orders includes Milliken's 20 July 1864 letter concerning Private Charles Garner, who had refused to return to the regiment after a hospital stint and sent an "impudent & insubordinate message." A 25 February 1865 printed order from General Godfrey Weitzel, commander of the new all-Black 25th Army Corps, announces that the new Corps badge would be a square: "Soldiers! To you is given a chance, in this Spring Campaign, of making this badge immortal. Let History record that on the banks of the James, thirty thousand freemen, not only gained their liberty, but shattered the prejudice of the world."

Other military papers of note include Milliken's 1863 discharge from his New York regiment signed by future artillery general John C. Tidball, and his 1863 commission as lieutenant of the USCT signed by Secretary of War Edwin Stanton.

The collection also includes dozens of family letters written before, during and after the war. Among the letters received by Milliken is a partial letter from his sister Anna: "Do you know that I at one time intended to come to Alexandria this fall to teach contrabands? I suppose I should have done so, had there been an opening there. . . . I feel as though I must be doing something to help that poor degraded ignorant people, to help fit them for the freedom so suddenly bestowed upon them. I learn there is a great need of a school there, if some official could be found who would undertake." Other family papers include: a 12-page fragment of a diary kept by William's mother Harriette Foster Milliken (1805-1872) in Clarendon, NY, January to June 1860; and 23 worn photographs, most of the circa 1860s cartes-de-visite, of friends and family members, 4 of them possibly depicting Lieutenant Milliken in civilian garb.

An unusually extensive collection spanning the entire existence of the 22nd United States Colored Troops, and more.

William Delville Milliken (1837-1887) of Albion, NY enlisted as a private in the all-white 4th New York Heavy Artillery in August 1862. In December 1863, he became a lieutenant in the 22nd United States Colored Troops, a regiment composed largely of Black recruits from New Jersey.

This lot includes 28 letters home which Milliken wrote as a lieutenant with the Colored Troops. The first three are written from basic training at Camp William Penn, the best known training base for the new Black regiments. On 7 January 1864 he wrote: "When I came here the men of my Co. did not know the first thing about drill, but you would be surprised to see how fast they learn. . . . I have seen many white troops with more drill do worse." On 16 January, he wrote "Lt. Heiner & myself went to town (Phil.) yesterday to see if we could not find out in what manner or who the parties were that swindled the Black men out of their bounty for so much." On 28 January, he expressed a wish to make "a few of those miserable sneaking Copperheads . . . drill with the Negroes a few days. How I do despise such traitors. . . . I wish you could be here to see the colored population come to camp to see their friends. It is gay, I assure you."

After the regiment deployed to Yorktown, VA, Milliken wrote a letter to his grandmother: "I like my colored soldiers very much. They are not perfect, neither are the white soldiers. We have very little trouble with them. They learn fast & are very attentive to what is being said to them. In time they will become as good fighters as the white boys" (7 April).

As the regiment settled in for the Siege of Petersburg, Milliken described his personal servant on 22 June: "I have one of the best of boys for a servant, carried all my things on a march & looks out generally for my uniform & comfort, cooks, & in fact is handy at anything. . . . Yesterday the President & Gen'l Grant came up to see the boys. Gen. Grant acknowledged by salute by saying 'How do you do, lieut.' . . . Pres. Lincoln looked much better than when I last seen him . . . more fleshy. Doubtless he & Gen. G. were pleased with all they saw."

Five days later, the regiment was under heavy fire: "A battery was erected immediately in front of our reg't. As soon as morning broke & discovered the fact to the Rebs, they opened a most terrible fire on said battery, & of course we suffered as much as the B. For an hour, a perfect shower of shot & shell rained upon us, but fortunately only 6 men in the whole reg't were hit. . . . The sharpshooters of the Rebs take great delight in shooting at Negroes." A partial letter written just after the 30 July Battle of the Crater reports that "our reg't lost during the day probably 6 or 8 killed & wounded."

22 November found Milliken detailed to the regimental headquarters, where he described the Black office staff: "Two drummer boys (which we keep here at headq'rs for orderlies) are dozeing off at my left. On my right is my table, & at it sit the serg't major & a clerk making out a list of absentees." He was miffed that a hometown acquaintance had not visited while in the area: "Perhaps he felt ashamed to let anyone know he had an acquaintance in a Col'd Reg't. If he was, I am very very glad I did not see him. Mrs. Reed only shows her ignorance when she talks as she does about col'd troops." Milliken notes that General Butler recently called the 22nd "the best Col'd Reg't in the U.S. service. . . . I doubt whether any white reg't in the Department stands higher in his favor."

The regiment suffered heavy losses at the 27 October 1864 Battle of Fair Oaks, which was widely attributed to the drunken state of its commander Colonel Joseph Barr Kiddoo. Milliken discusses this allegation in his 27 November letter: "I am very sorry to say that I think Col. Kiddoo was a little tight on the day of our last fight. Several of us were so strongly impressed with that belief that we did apply for a court of inquiry. . . . Our reg't has had & earned a good name & to have it lost in this style is more than we care to bear." The next day, Milliken was one of six company officers who signed a formal accusation against his colonel, as published in the official records of the Union Army.

On 17 April 1865, two days after the assassination, Milliken told his father: "We start tonight for Washington to participate in the funeral exercises of President Lincoln (late). I feel it quite an honor, but a very sad one." On 20 May 1865, he wrote "What do you think of Jeff D now? How comical the ending of the Great Rebellion." The regiment spent the last months of the war in Brownsville, TX on the Mexican border. A manuscript copy of a 26 July 1865 order explains the use of aloe to avoid scurvy, ordering a detachment of one officer and 25 men to head into the wilderness with a guide to collect it.

20 earlier Civil War letters were written while Milliken was a private in the 4th New York Heavy Artillery, stationed in the defenses of Washington. The regiment was initially led by Colonel Thomas Donnelly Doubleday, brother of the well-known Abner Doubleday. Two of the letters are on illustrated regimental letterhead, one naming Doubleday as commander. On 14 September 1863 Milliken discusses his thoughts on a possible new venture: "I have thought a great deal of late about the Negro reg'ts. I believe there is the place for men to show their patriotism & as far as what the world & the rest of mankind would say, I do not care one fig for." He announces on 11 December that he passed the board of examiners and was commissioned a second lieutenant.

The 51 manuscript regimental and brigade reports in this lot include several listing soldier names. They include the muster-in roll of Company E dated 12 January 1864, listing the 100 members of the company with their age and home town. New Jersey and Delaware soldiers are predominant. A Company E clothing roll from August 1864 includes the signatures of 39 soldiers, almost all of them by mark. A statement of charges for the first quarter of 1864 lists 5 soldiers who are charged for losing gear, along with the circumstances of the loss. Another is a "List of men on duty at Headquarters" spanning from January to September 1865, listing 19 enlisted men and their duties at the headquarters as clerks, a nurse, an orderly, and several "Regimental Pioneers."

A thick sheaf of 115 official company and regimental letters and orders includes Milliken's 20 July 1864 letter concerning Private Charles Garner, who had refused to return to the regiment after a hospital stint and sent an "impudent & insubordinate message." A 25 February 1865 printed order from General Godfrey Weitzel, commander of the new all-Black 25th Army Corps, announces that the new Corps badge would be a square: "Soldiers! To you is given a chance, in this Spring Campaign, of making this badge immortal. Let History record that on the banks of the James, thirty thousand freemen, not only gained their liberty, but shattered the prejudice of the world."

Other military papers of note include Milliken's 1863 discharge from his New York regiment signed by future artillery general John C. Tidball, and his 1863 commission as lieutenant of the USCT signed by Secretary of War Edwin Stanton.

The collection also includes dozens of family letters written before, during and after the war. Among the letters received by Milliken is a partial letter from his sister Anna: "Do you know that I at one time intended to come to Alexandria this fall to teach contrabands? I suppose I should have done so, had there been an opening there. . . . I feel as though I must be doing something to help that poor degraded ignorant people, to help fit them for the freedom so suddenly bestowed upon them. I learn there is a great need of a school there, if some official could be found who would undertake." Other family papers include: a 12-page fragment of a diary kept by William's mother Harriette Foster Milliken (1805-1872) in Clarendon, NY, January to June 1860; and 23 worn photographs, most of the circa 1860s cartes-de-visite, of friends and family members, 4 of them possibly depicting Lieutenant Milliken in civilian garb.

An unusually extensive collection spanning the entire existence of the 22nd United States Colored Troops, and more.

Exhibition Hours

Exhibition Hours

Aliquam vulputate ornare congue. Vestibulum maximus, libero in placerat faucibus, risus nisl molestie massa, ut maximus metus lectus vel lorem.