Sale 2697 - Lot 279

Price Realized: $ 3,000

Price Realized: $ 3,750

?Final Price Realized includes Buyer’s Premium added to Hammer Price

Estimate: $ 800 - $ 1,200

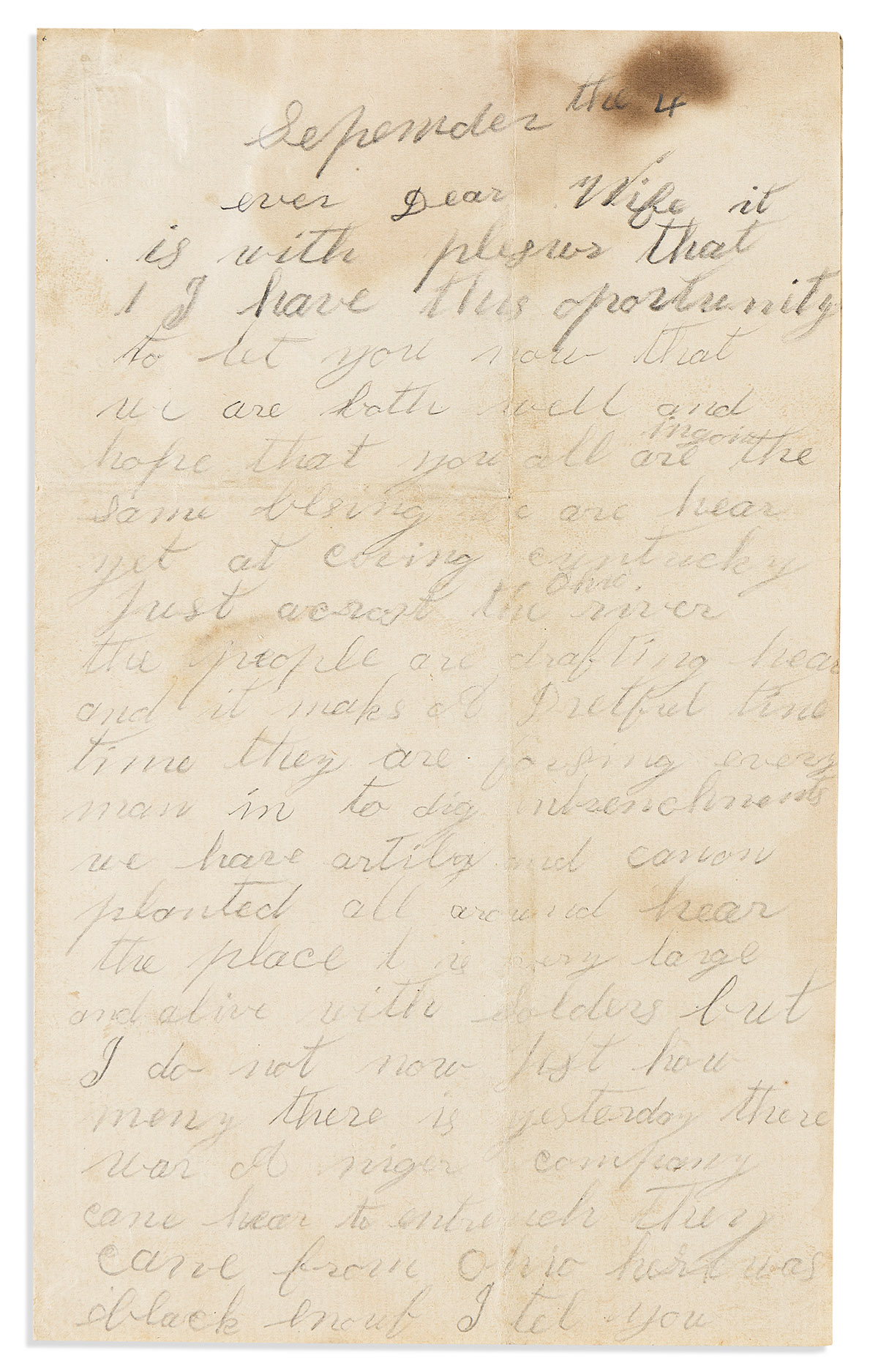

(MILITARY--CIVIL WAR.) Rare mention of the Black Brigade of Cincinnati and other content in an Ohio soldier's letters. 6 Autograph Letters Signed by Private Alfred A. Thayer to wife Annie Thayer of Mount Vernon, OH, each 4 or 6 pages, about 8 x 5 inches; minor wear and staining. Each with its original stamped and postmarked mailing envelope. Various places, 1862-1864

Additional Details

The first of these letters, written on 4 September 1862, mentions the first days of the Black Brigade of Cincinnati, perhaps the first Black soldiers on active duty in the Union army.

A scarcely literate white private, Alfred Thayer, had been rushed with his newly formed regiment to Covington, Kentucky to defend Cincinnati against an expected Confederate raid. He noted: "They are forsing in every man in to dig intrenchments. We have artily and canon planted all around hear. The place being is very large and alive with solders. . . . Yesterday there was a niger company came hear to entrench. They came here from Ohio. Here was black enouf, I tel you. We look for an atack all the time."

The soldier was obviously surprised to see a company of Black soldiers. We should also be surprised, this early in the war. At this point the First Kansas Colored Infantry had started recruiting but had not been mustered; the 1st Louisiana Native Guard would be organized later that month, and Lincoln had not yet issued his preliminary Emancipation Proclamation. The formation of the 54th Massachusetts and United States Colored Troops regiments was still months away.

These troops were pressed into duty only because the Confederate Army of Kentucky was marching on a largely defenseless city. On 2 September, the Cincinnati police began forcibly impressing the city's Black regiments, and forced about 400 of them across the river to Kentucky at bayonet point to help build fortifications. They worked for 36 hours straight with little food and little explanation of when they would be freed. This disturbing and often forgotten episode was the first use of Black troops in the Union Army--and what Private Thayer witnessed with such astonishment.

On 4 September, the day Thayer wrote his letter, other Union military leaders put a stop to this quasi-enslavement, released the soldiers, and called for them to enlist properly as volunteers. They spent the next few weeks continuing to develop the city's defenses before their discharge. Working under white officers, they were never issued weapons, and were quite vulnerable to any Confederate assault--which fortunately never came.

Thayer's second letter was written on 30 October 1862 after the threat had passed, with his regiment marching through Kentucky. He wrote: "This hole cuntry is full of solders and negrows. As we pass along the road we can count from 20 to 30 in a plase. I ask them whare there masters is & they say, 'in the reble armey.'"

A 12 January 1863 letter from the Siege of Vicksburg discusses the use of contraband labor on a canal intended to bypass the Confederate fort: "We are still laying hear in a mud hole in plane site of Vitchburg & doing nothing, onley making mud bridges & the negro working on the cannal."

The 14 June 1863 letter was written near the end of the Vicksburg siege. He described the Confederate use of enslaved workers as human shields: "They can't rule for they are to wicked. In some of these fites down hear they have taken there negrows & chained them to there canon so they coudent run. We have taken there canon & fond their negrows ded, chaned to the canons."

While some white Union soldiers were good abolitionists, others were more conflicted--Thayer among them. On 29 September 1864 he told his wife of his support for a colonization plan after the war: "I don't want you to have anything to do with the negrows, for as soon as this war is over we will have to put them down, for they begin to think they are better than a white person now, & used beter by the ofesers all threw the armey. If they ever do rebel, I am one to help put them down. I believe when this war is over not to allow a colard person in the northern states. Give them som place to go to, then make them go. I want nothing to do with negrows nor negrows lovers. This is the kind of an abolishin I am. I believe in usen them well till we get a plase for them, that's all."

Thayer reiterates these sentiments in his final letter dated from Louisiana, 13 October 1864: "The negrow ain't beter sogers than they mite be. I believe in freen them, that all."

The author Alfred Alverson Thayer (1838-1878) was a white soldier from Mount Vernon, Ohio who served as a private in the 96th Ohio Infantry from August 1862 through the end of the war.

A scarcely literate white private, Alfred Thayer, had been rushed with his newly formed regiment to Covington, Kentucky to defend Cincinnati against an expected Confederate raid. He noted: "They are forsing in every man in to dig intrenchments. We have artily and canon planted all around hear. The place being is very large and alive with solders. . . . Yesterday there was a niger company came hear to entrench. They came here from Ohio. Here was black enouf, I tel you. We look for an atack all the time."

The soldier was obviously surprised to see a company of Black soldiers. We should also be surprised, this early in the war. At this point the First Kansas Colored Infantry had started recruiting but had not been mustered; the 1st Louisiana Native Guard would be organized later that month, and Lincoln had not yet issued his preliminary Emancipation Proclamation. The formation of the 54th Massachusetts and United States Colored Troops regiments was still months away.

These troops were pressed into duty only because the Confederate Army of Kentucky was marching on a largely defenseless city. On 2 September, the Cincinnati police began forcibly impressing the city's Black regiments, and forced about 400 of them across the river to Kentucky at bayonet point to help build fortifications. They worked for 36 hours straight with little food and little explanation of when they would be freed. This disturbing and often forgotten episode was the first use of Black troops in the Union Army--and what Private Thayer witnessed with such astonishment.

On 4 September, the day Thayer wrote his letter, other Union military leaders put a stop to this quasi-enslavement, released the soldiers, and called for them to enlist properly as volunteers. They spent the next few weeks continuing to develop the city's defenses before their discharge. Working under white officers, they were never issued weapons, and were quite vulnerable to any Confederate assault--which fortunately never came.

Thayer's second letter was written on 30 October 1862 after the threat had passed, with his regiment marching through Kentucky. He wrote: "This hole cuntry is full of solders and negrows. As we pass along the road we can count from 20 to 30 in a plase. I ask them whare there masters is & they say, 'in the reble armey.'"

A 12 January 1863 letter from the Siege of Vicksburg discusses the use of contraband labor on a canal intended to bypass the Confederate fort: "We are still laying hear in a mud hole in plane site of Vitchburg & doing nothing, onley making mud bridges & the negro working on the cannal."

The 14 June 1863 letter was written near the end of the Vicksburg siege. He described the Confederate use of enslaved workers as human shields: "They can't rule for they are to wicked. In some of these fites down hear they have taken there negrows & chained them to there canon so they coudent run. We have taken there canon & fond their negrows ded, chaned to the canons."

While some white Union soldiers were good abolitionists, others were more conflicted--Thayer among them. On 29 September 1864 he told his wife of his support for a colonization plan after the war: "I don't want you to have anything to do with the negrows, for as soon as this war is over we will have to put them down, for they begin to think they are better than a white person now, & used beter by the ofesers all threw the armey. If they ever do rebel, I am one to help put them down. I believe when this war is over not to allow a colard person in the northern states. Give them som place to go to, then make them go. I want nothing to do with negrows nor negrows lovers. This is the kind of an abolishin I am. I believe in usen them well till we get a plase for them, that's all."

Thayer reiterates these sentiments in his final letter dated from Louisiana, 13 October 1864: "The negrow ain't beter sogers than they mite be. I believe in freen them, that all."

The author Alfred Alverson Thayer (1838-1878) was a white soldier from Mount Vernon, Ohio who served as a private in the 96th Ohio Infantry from August 1862 through the end of the war.

Exhibition Hours

Exhibition Hours

Aliquam vulputate ornare congue. Vestibulum maximus, libero in placerat faucibus, risus nisl molestie massa, ut maximus metus lectus vel lorem.