Sale 2615 - Lot 394

Price Realized: $ 800

Price Realized: $ 1,000

?Final Price Realized includes Buyer’s Premium added to Hammer Price

Estimate: $ 500 - $ 750

(PERU.) Charles J. MacConnell. Letters from an early American tourist on the Peruvian Central Railway, and more. 6 Autograph Letters to wife, all about 8 x 5 inches and ranging from 5 to 13 pages long; 3 of the letters lacking signatures and possibly incomplete. With full transcripts of all letters. Various places, 1873-1874, 1877

Additional Details

The Peruvian Central Railway was an ambitious mountainous line which began construction in 1870 and was not completed until 1908. It remains in operation, and has been submitted as a UNESCO World Heritage site for its engineering marvels and its evocation of Peru's arrival in the industrial era.

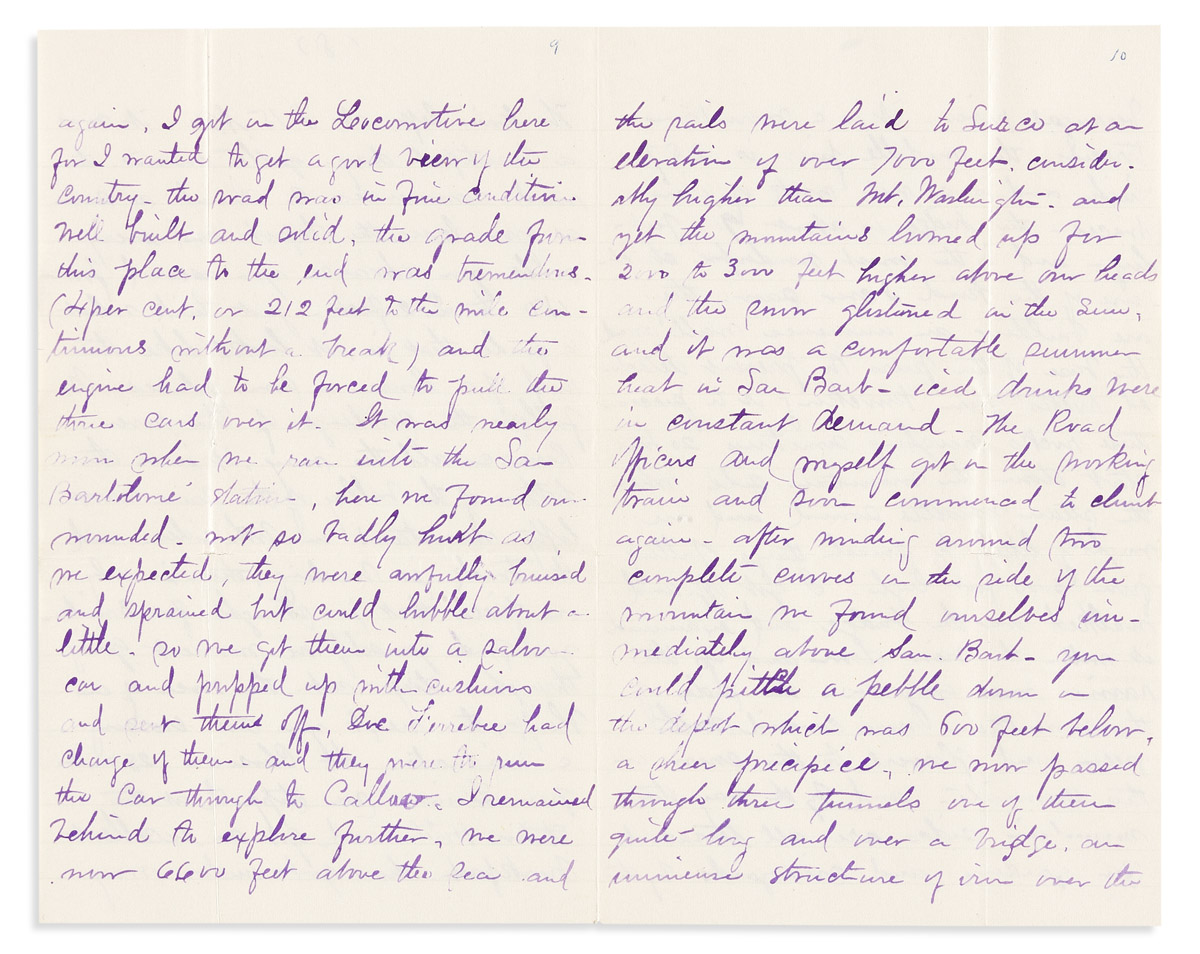

Charles J. MacConnell (1837-1909) was a Pennsylvanian who graduated from the New Jersey State Normal School (now the College of New Jersey), enlisted in the Navy during the Civil War, and remained in the service afterward. At the time he wrote most of these letters, he was First Assistant Engineer aboard the USS Pensacola in the Pacific Squadron. He wrote four of these letters off the coast of Peru, or in the coastal city of Callao. The first of his letters, dated 20 April 1873, describes a visit to the tomb of Pizarro, where one of his ugly American colleagues offers to buy Pizarro's skull and attempts to purloin a toe bone. He is then invited to join a party of officers on the new railroad up to the mining center in La Oroya, but misses the train. He soon learns by telegraph that the train had derailed: "One had broken his leg, another was paralyzed, and another had his head split open, another his back broken, the conductor was so much injured that he would probably die." McConnell then took the next train up to San Bartolomé to help retrieve his wounded comrades. He sat in the locomotive for a better view, and found the railroad a marvel: "the road commences to climb as soon as you leave the depot . . . it looks like the roof of a house in some places." In San Bartolomé he helped load the wounded naval men into the car for the return trip, then stayed on the mountain-bound train to explore to the end of the road: "The roads were laid to Surco at an elevation of over 7000 feet, considerably higher than Mount Washington, and yet the mountains loomed up for 2000 to 2000 feet higher above our heads and the snow glistened in the sun." He gave the measurements of the famed bridge over the Rio Verrugas, adding that "it is the most magnificent structure of the kind I ever saw. . . rocks weighing sometimes 20 tons start down the mountain side when the steam whistles sound and are mighty likely to smash things. . . . These mountain sides are all terraced for gardens and vineyards by the ancient Peruvians hundreds of years ago, but now in ruins." McConnell's 24 April letter continues the story with an account of the ongoing rail construction at Surco: "They are digging, tunneling, and blasting beyond us, but no rails are laid yet. From this point, all the supplies etc. have to be transported on the backs of mules to the elevations under 10,000 feet. Above that they employ llamas, a beast peculiar to these regions. . . . They always have a leader who is as proud as a peacock with holes bored in the tips of his ears, in which are placed knots of brightly colored ribbons. . . . No other animals can live up here."

MacConnell's 8 July 1873 letter describes a grand ball at the Lima home of railroad magnate Henry Meiggs, and on 14 March 1874 he describes another trip up the Peruvian Central Railway, which extended 15 miles further past San Bartolomé than during his first visit. "I climbed up the side of a mountain on horseback and went in Tunnel No. 15 to see them at work. They had run the heading in some 750 feet in the hardest rock I ever saw, and were drilling away using a diamond drill worked with compressed air. . . . The grade is such that it would utterly demoralize any ordinary railroad engineer. . . . In Tunnel 15 they have already killed 500 men . . . from the effects of foul air, accidents, etc." He concluded with a jolly visit to the American engineer Van Brocklin at his home in Matucana: "gentlemen, well bred and thoroughly educated, roughing it, as you are obliged to do in a place like this, with rough unkempt beards, booted to the thighs, heavy ponchos on the shoulders, slouched hats, big spurs clanking, a revolver buckled in the waist."

One of MacConnell's 1873 letters was written off Talcahuano, Chile. He describes a long excursion into the country by rail to San Rosenda, Chile, and then 40 miles further on a construction train as far as Cabrera station. One final letter was written from Cairo, Egypt in 1879 while serving aboard the USS Monongahela.

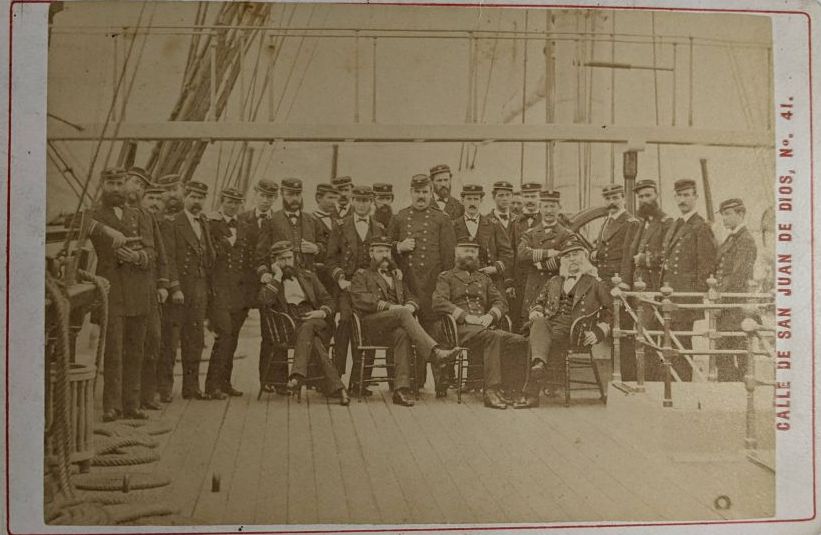

WITH--a cabinet card depicting MacConnell and the rest of his Pensacola crew on deck off Valparaiso, Chile in 1873.

Charles J. MacConnell (1837-1909) was a Pennsylvanian who graduated from the New Jersey State Normal School (now the College of New Jersey), enlisted in the Navy during the Civil War, and remained in the service afterward. At the time he wrote most of these letters, he was First Assistant Engineer aboard the USS Pensacola in the Pacific Squadron. He wrote four of these letters off the coast of Peru, or in the coastal city of Callao. The first of his letters, dated 20 April 1873, describes a visit to the tomb of Pizarro, where one of his ugly American colleagues offers to buy Pizarro's skull and attempts to purloin a toe bone. He is then invited to join a party of officers on the new railroad up to the mining center in La Oroya, but misses the train. He soon learns by telegraph that the train had derailed: "One had broken his leg, another was paralyzed, and another had his head split open, another his back broken, the conductor was so much injured that he would probably die." McConnell then took the next train up to San Bartolomé to help retrieve his wounded comrades. He sat in the locomotive for a better view, and found the railroad a marvel: "the road commences to climb as soon as you leave the depot . . . it looks like the roof of a house in some places." In San Bartolomé he helped load the wounded naval men into the car for the return trip, then stayed on the mountain-bound train to explore to the end of the road: "The roads were laid to Surco at an elevation of over 7000 feet, considerably higher than Mount Washington, and yet the mountains loomed up for 2000 to 2000 feet higher above our heads and the snow glistened in the sun." He gave the measurements of the famed bridge over the Rio Verrugas, adding that "it is the most magnificent structure of the kind I ever saw. . . rocks weighing sometimes 20 tons start down the mountain side when the steam whistles sound and are mighty likely to smash things. . . . These mountain sides are all terraced for gardens and vineyards by the ancient Peruvians hundreds of years ago, but now in ruins." McConnell's 24 April letter continues the story with an account of the ongoing rail construction at Surco: "They are digging, tunneling, and blasting beyond us, but no rails are laid yet. From this point, all the supplies etc. have to be transported on the backs of mules to the elevations under 10,000 feet. Above that they employ llamas, a beast peculiar to these regions. . . . They always have a leader who is as proud as a peacock with holes bored in the tips of his ears, in which are placed knots of brightly colored ribbons. . . . No other animals can live up here."

MacConnell's 8 July 1873 letter describes a grand ball at the Lima home of railroad magnate Henry Meiggs, and on 14 March 1874 he describes another trip up the Peruvian Central Railway, which extended 15 miles further past San Bartolomé than during his first visit. "I climbed up the side of a mountain on horseback and went in Tunnel No. 15 to see them at work. They had run the heading in some 750 feet in the hardest rock I ever saw, and were drilling away using a diamond drill worked with compressed air. . . . The grade is such that it would utterly demoralize any ordinary railroad engineer. . . . In Tunnel 15 they have already killed 500 men . . . from the effects of foul air, accidents, etc." He concluded with a jolly visit to the American engineer Van Brocklin at his home in Matucana: "gentlemen, well bred and thoroughly educated, roughing it, as you are obliged to do in a place like this, with rough unkempt beards, booted to the thighs, heavy ponchos on the shoulders, slouched hats, big spurs clanking, a revolver buckled in the waist."

One of MacConnell's 1873 letters was written off Talcahuano, Chile. He describes a long excursion into the country by rail to San Rosenda, Chile, and then 40 miles further on a construction train as far as Cabrera station. One final letter was written from Cairo, Egypt in 1879 while serving aboard the USS Monongahela.

WITH--a cabinet card depicting MacConnell and the rest of his Pensacola crew on deck off Valparaiso, Chile in 1873.

Exhibition Hours

Exhibition Hours

Aliquam vulputate ornare congue. Vestibulum maximus, libero in placerat faucibus, risus nisl molestie massa, ut maximus metus lectus vel lorem.