Sale 2505 - Lot 351

Price Realized: $ 5,400

Price Realized: $ 6,750

?Final Price Realized includes Buyer’s Premium added to Hammer Price

Estimate: $ 6,000 - $ 9,000

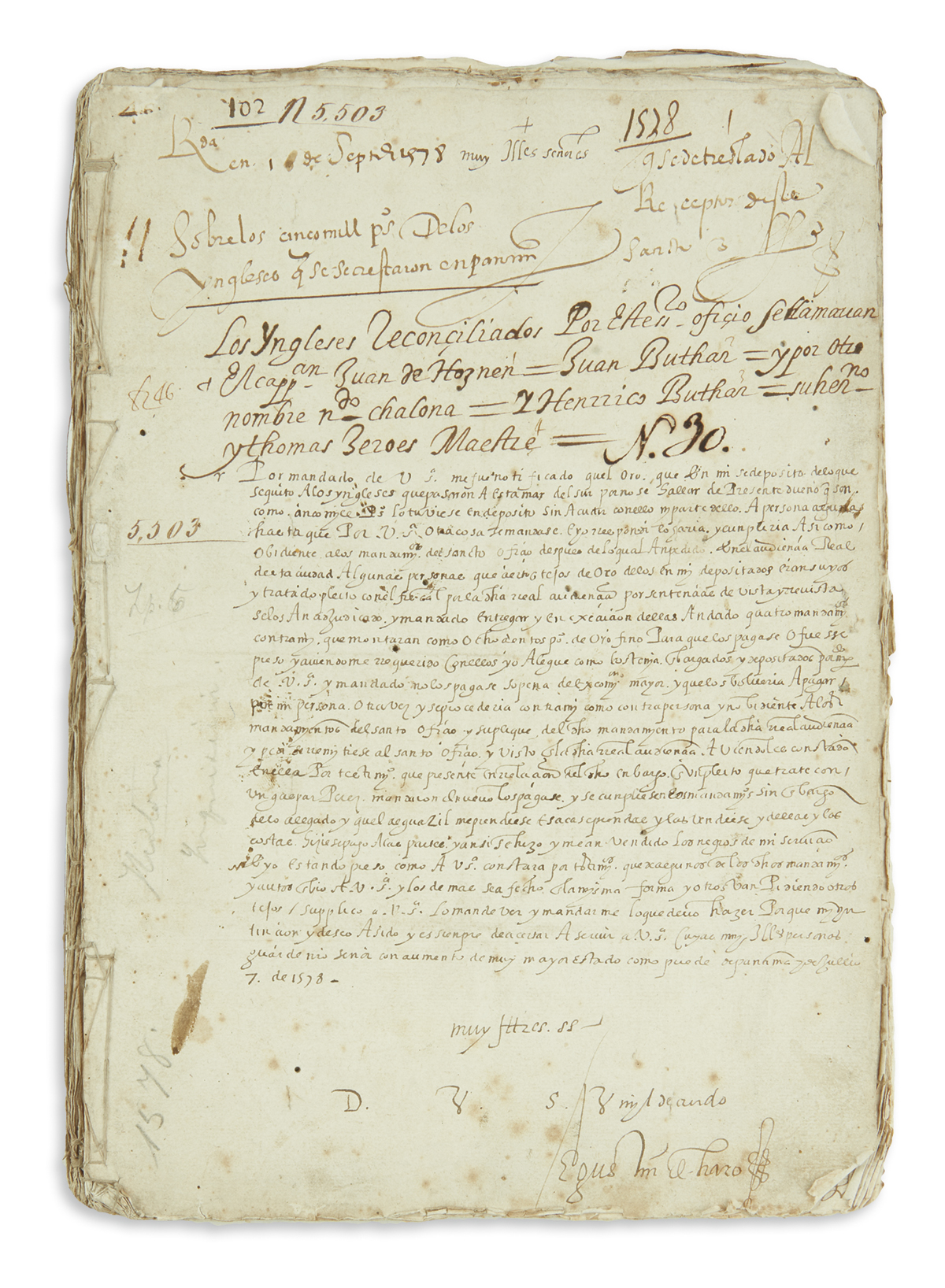

(PIRATES.) Extensive file on efforts to recover the treasure looted by English privateer John Oxenham in Panama. 46 manuscript leaves plus additional blanks (some with docketing), 12 1/2 x 9 inches, stitched; minor wear and worming. Vp, 1578-83

Additional Details

John Oxenham was an English privateer who first came to America under Sir Francis Drake in 1572. From 1576 to 1578 he led a bold expedition to Spanish-held Panama. With support from the local Cimarron runaway slave community, he and his 57 men wintered at Panama, built a ship on the Pacific coast, and in the spring launched a surprise attack on Spanish ships loaded with Peruvian gold and silver. They were eventually pursued upriver and were able to bury some of their treasure. Oxenham and a few of his men fled into the interior and evaded capture for several months, but were eventually captured in Venezuela in 1578.

Offered here is a detailed file on Spanish efforts to recover this treasure. Oxenham (appearing in the documents in this lot as "Juan de Hoznen") and the others were found with around 5,000 pesos of gold and silver. Agustín de Haro, the accountant of the royal treasury in Panama, was entrusted with the money. Some who had participated in the defeat and capture of the pirates claimed they were owed a share of the treasure for their efforts, and demanded it from Haro. However, the Holy Office of the Inquisition had a legal claim to all of the money. The captured pirates were in the Inquisition's custody and would be tried in its courts. Because Oxenham and his crew were not Catholics, they were charged with heresy and apostasy, and thus they and their property fell under the jurisdiction of the Holy Inquisition. Haro would not budge, however, claiming that he was given strict orders to not deliver the money to anyone, for any circumstances, until he received orders from the highest authorities claiming otherwise. Haro was eventually jailed for his intransigence.

Official orders regarding the treasure were postponed due to the absence of the comisario of Panama City, Juan Constantino, on missionary work. Haro would die in jail (possibly of suicide) before the comisario could return to resolve the issue. Baltasar de Melo, the tribunal official who collected money and received evidence, complains about the comisario's persistent absenteeism, and how it indefinitely postponed the resolution of crucial issues surrounding the capture of the pirates: "Es cosa perdida tenerlo aquí por Comisario porque los negocios perecen por su falta y ausencia. ¿Qué poco sirve que vengan de allá mandamientos si no hay acá quien los ejecute?" ("It is a waste to have him here as the commissioner because matters languish as a result of his unavailability and absence. What good does it do to have orders coming from far away if there is no one here to execute them?")

One such issue put on hold was the fate of the pirates themselves--including Oxenham and his sidekicks John Butler ("Juan Buthar/Butlar," known among Spaniards as Chalona) and brother Henry ("Henrrico Buthar"). They had been languishing in their cells, with little progress made on their cases, again because of the comisario's absence. The pirates (who are mentioned in nearly every document) are spoken of in the present tense (se llaman, or "they are named"), and are mentioned as currently being imprisoned. The above three, who had gained considerable notoriety in the Hispanic world for their previous ventures with Francis Drake ("Chalona" was supposedly renowned for his navigational expertise), are always mentioned by name, along with the maestre "Thomas Jeroes" (Thomas Sherwell). None of the other Englishmen are named, and, curiously, nothing is said of the runaway slaves who avoided execution by being re-enslaved. Authorities eventually received the approval to move Oxenham, the Butlers, Sherwell, and the other more prominent pirates to Lima, where they were publicly executed in 1580. When the texts move forward into the 1580s, the pirates are referred to in the past tense.

The deaths of the pirates and the death of Haro would do nothing to bring back all of the missing wealth. The home of the deceased Haro showed no trace of lost silver and gold, and his estate amounted to little more than worthless "cachivaches y menajes de casa" ("pieces of junk and household items"). As it would turn out, the real reason why Haro refused to distribute the money, and why none of it could be found in his house, was that he had used it. Haro had been lending out the pirate's loot to several people as far away as Cuzco. Juan de Saracho, another receptor of the Inquisition, petitioned the tribunal to authorize him to side-step the comisario's absence and collect every last peso of gold and silver from those Haro had lent to. He also asked for the authority to threaten anyone who refused to cooperate with excommunication. Saracho's petition received approval from the Inquisition in Lima. Soon, he and the other receptor, the aforementioned Melo, ruthlessly demanded the immediate repayment of the loans made with the pirate treasure. While they were able to retrieve much of the money this way, their strong-arm tactics were met with resistance. Included here is a 1583 petition by the family members and descendants of the late Gabriel de Loarte, a leading official whom Saracho and Melo had been targeting, complaining of the harassment. They argued that their father had received the loans from Haro, not them. The last document is a ledger from 1583 showing the enormous amount the two had collected, and the remaining amount, which, for all that is known, may have never been recouped.

Offered here is a detailed file on Spanish efforts to recover this treasure. Oxenham (appearing in the documents in this lot as "Juan de Hoznen") and the others were found with around 5,000 pesos of gold and silver. Agustín de Haro, the accountant of the royal treasury in Panama, was entrusted with the money. Some who had participated in the defeat and capture of the pirates claimed they were owed a share of the treasure for their efforts, and demanded it from Haro. However, the Holy Office of the Inquisition had a legal claim to all of the money. The captured pirates were in the Inquisition's custody and would be tried in its courts. Because Oxenham and his crew were not Catholics, they were charged with heresy and apostasy, and thus they and their property fell under the jurisdiction of the Holy Inquisition. Haro would not budge, however, claiming that he was given strict orders to not deliver the money to anyone, for any circumstances, until he received orders from the highest authorities claiming otherwise. Haro was eventually jailed for his intransigence.

Official orders regarding the treasure were postponed due to the absence of the comisario of Panama City, Juan Constantino, on missionary work. Haro would die in jail (possibly of suicide) before the comisario could return to resolve the issue. Baltasar de Melo, the tribunal official who collected money and received evidence, complains about the comisario's persistent absenteeism, and how it indefinitely postponed the resolution of crucial issues surrounding the capture of the pirates: "Es cosa perdida tenerlo aquí por Comisario porque los negocios perecen por su falta y ausencia. ¿Qué poco sirve que vengan de allá mandamientos si no hay acá quien los ejecute?" ("It is a waste to have him here as the commissioner because matters languish as a result of his unavailability and absence. What good does it do to have orders coming from far away if there is no one here to execute them?")

One such issue put on hold was the fate of the pirates themselves--including Oxenham and his sidekicks John Butler ("Juan Buthar/Butlar," known among Spaniards as Chalona) and brother Henry ("Henrrico Buthar"). They had been languishing in their cells, with little progress made on their cases, again because of the comisario's absence. The pirates (who are mentioned in nearly every document) are spoken of in the present tense (se llaman, or "they are named"), and are mentioned as currently being imprisoned. The above three, who had gained considerable notoriety in the Hispanic world for their previous ventures with Francis Drake ("Chalona" was supposedly renowned for his navigational expertise), are always mentioned by name, along with the maestre "Thomas Jeroes" (Thomas Sherwell). None of the other Englishmen are named, and, curiously, nothing is said of the runaway slaves who avoided execution by being re-enslaved. Authorities eventually received the approval to move Oxenham, the Butlers, Sherwell, and the other more prominent pirates to Lima, where they were publicly executed in 1580. When the texts move forward into the 1580s, the pirates are referred to in the past tense.

The deaths of the pirates and the death of Haro would do nothing to bring back all of the missing wealth. The home of the deceased Haro showed no trace of lost silver and gold, and his estate amounted to little more than worthless "cachivaches y menajes de casa" ("pieces of junk and household items"). As it would turn out, the real reason why Haro refused to distribute the money, and why none of it could be found in his house, was that he had used it. Haro had been lending out the pirate's loot to several people as far away as Cuzco. Juan de Saracho, another receptor of the Inquisition, petitioned the tribunal to authorize him to side-step the comisario's absence and collect every last peso of gold and silver from those Haro had lent to. He also asked for the authority to threaten anyone who refused to cooperate with excommunication. Saracho's petition received approval from the Inquisition in Lima. Soon, he and the other receptor, the aforementioned Melo, ruthlessly demanded the immediate repayment of the loans made with the pirate treasure. While they were able to retrieve much of the money this way, their strong-arm tactics were met with resistance. Included here is a 1583 petition by the family members and descendants of the late Gabriel de Loarte, a leading official whom Saracho and Melo had been targeting, complaining of the harassment. They argued that their father had received the loans from Haro, not them. The last document is a ledger from 1583 showing the enormous amount the two had collected, and the remaining amount, which, for all that is known, may have never been recouped.

Exhibition Hours

Exhibition Hours

Aliquam vulputate ornare congue. Vestibulum maximus, libero in placerat faucibus, risus nisl molestie massa, ut maximus metus lectus vel lorem.