Sale 2619 - Lot 47

Price Realized: $ 26,000

Price Realized: $ 32,500

?Final Price Realized includes Buyer’s Premium added to Hammer Price

Estimate: $ 6,000 - $ 9,000

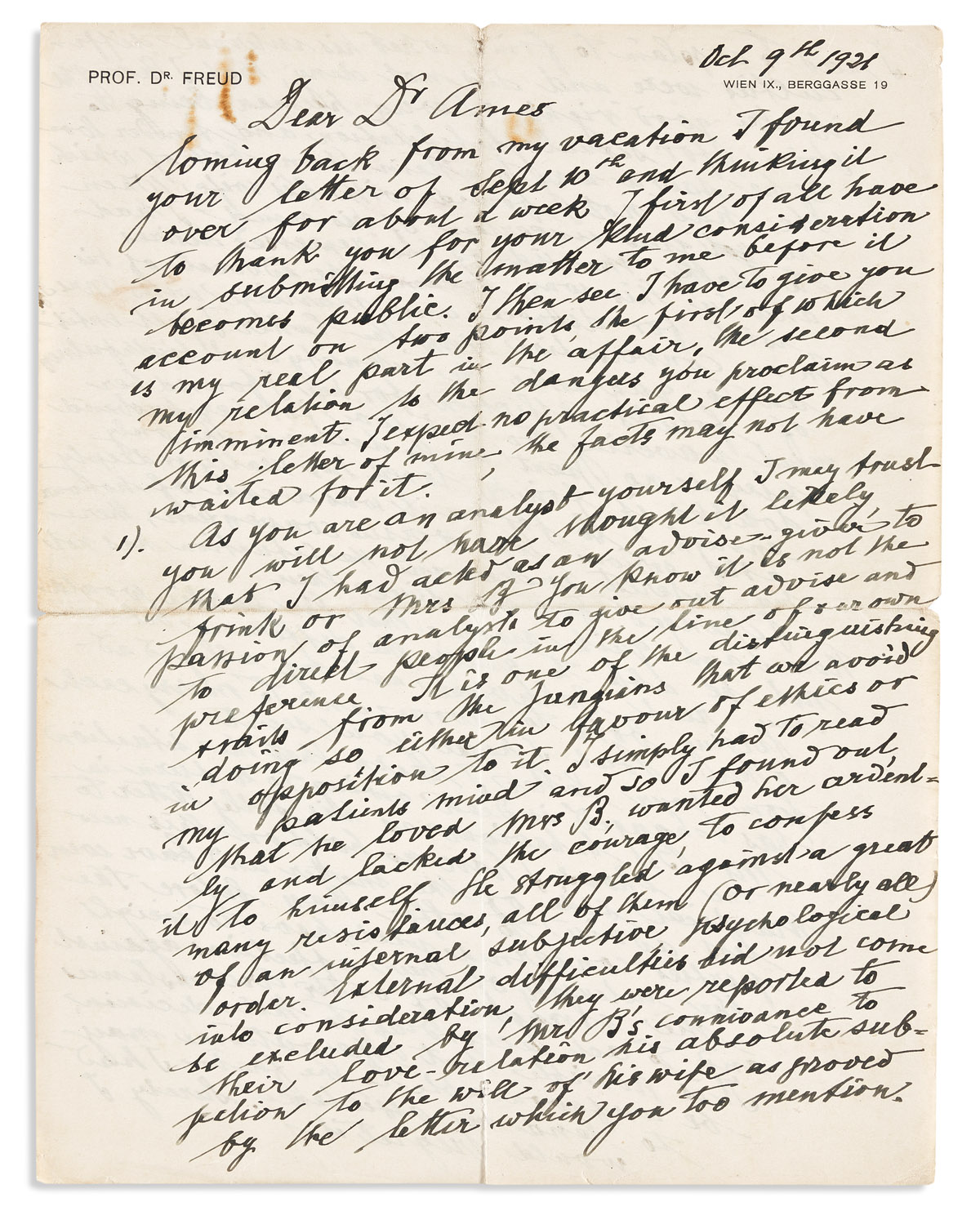

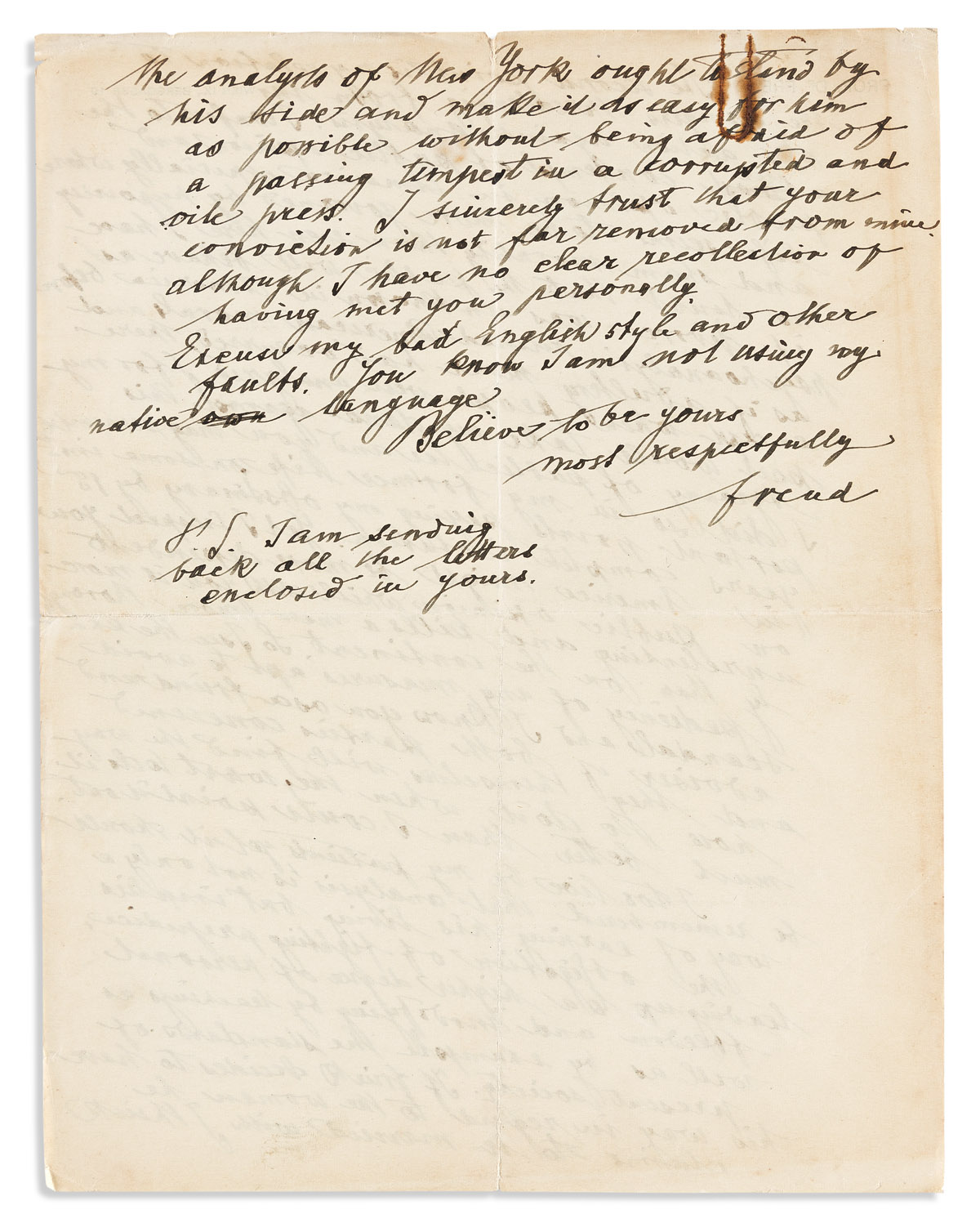

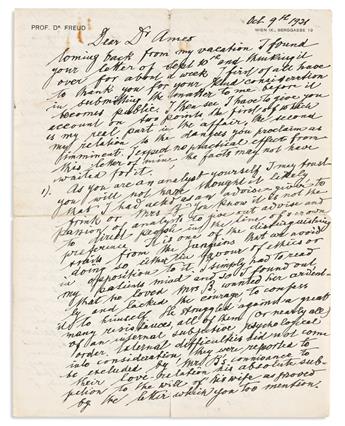

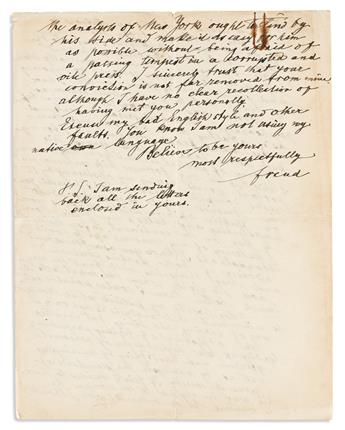

REACTING TO SCANDAL: "I CONFESS TO THE UTTER CONTEMPT OF PUBLIC OPINION" (SCIENTISTS.) FREUD, SIGMUND. Autograph Letter Signed, "Freud," to American psychoanalyst Thaddeus Hoyt Ames ("Dear Dr. Ames"), in English, asserting that Freud did not provide moral advice to his own patient despite what the media claim [the result of Freud's analysis of Mr. Frink suggested that Frink's divorce and pursuit of a married woman (Mrs. B.) would improve his health], explaining that it was necessary to advocate on behalf of Frink's repressed desires because of his condition, stating that humans have a right to pursue sexual gratification and tender love, expressing concern about the letter Freud received from the husband of Mrs. B., expressing contempt for--especially American--public opinion, expecting Americans to conclude that psychoanalysis is responsible for ruining American morals, committing to stand against American public opinion in this matter but sympathizing with Ames's need to maintain his business there, reminding Ames of his obligation as an analyst to live as a moral example and help improve the standards of society, apologizing for the errors due to having written in English and, in a postscript: "I am sending back all the letters enclosed in yours [not present]." 3 1/2 pages, 4to, "Prof. Dr. Freud" stationery, written on two sheets; short closed separations at folds, paper clip stains at upper edge throughout. Vienna, 9 October 1921

Additional Details

". . . I found your letter . . . and thinking it over for about a week I first of all have to thank you for your kind consideration in submitting the matter to me before it becomes public. I then see I have to give you account on two points, the first of which is my real part in the affair, the second my relation to the dangers you proclaim as imminent. . . .

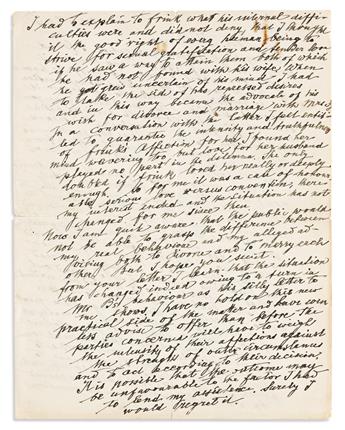

". . . As you are an analyst yourself I may trust you will not have thought it likely that I had acted as an advise-giver to Frink or Mrs B. You know it is not the passion of analysts to give out advise and to direct people in the line of our own preference. It is one of the distinguishing traits from the Jungians that we avoid doing so either in favour of ethics or in opposition to it. I simply had to read my patients mind and so I found out that he loved Mrs B., wanted her ardently and lacked the courage to confess it to himself. He struggled against a great many resistances, all of them . . . of an internal subjective psychological order. External difficulties did not come into consideration . . . .

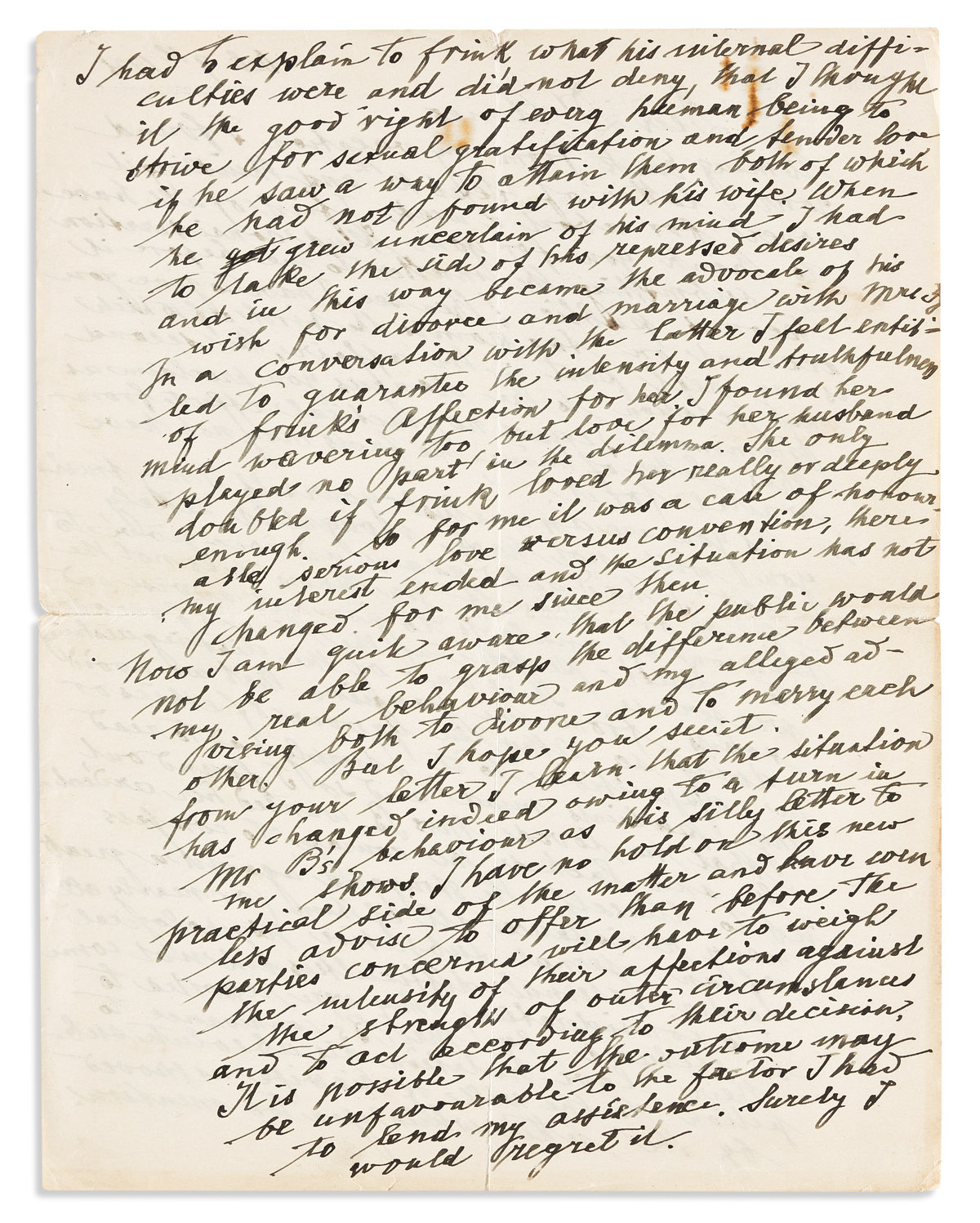

"I had to explain to Frink what his internal difficulties were and did not deny that I thought it the good right of every human being to strive for sexual gratification and tender love if he saw a way to attain them, both of which he had not found with his wife. When he grew uncertain of his mind I had to take the side of his repressed desires and in this way became the advocate of his wish for divorce and marriage with Mrs B. In a conversation with the latter I felt entitled to guarantee the intensity and truthfulness of Frink's affection for her. I found her mind wavering too, but love for her husband played no part in the dilemma. She only doubted if Frink loved her really or deeply enough. So for me it was a case of honourable serious love versus convention, there my interest ended and the situation has not changed for me since then.

"Now I am quite aware that the public would not be able to grasp the difference between my real behaviour and my alleged advising both to divorce and to marry each other. But I hope you see it. From your letter I learn that the situation has changed indeed owing to a turn in Mr B's behaviour as his silly letter to me shows. I have no hold on this new practical side of the matter and have even less advise to offer than before . . . .

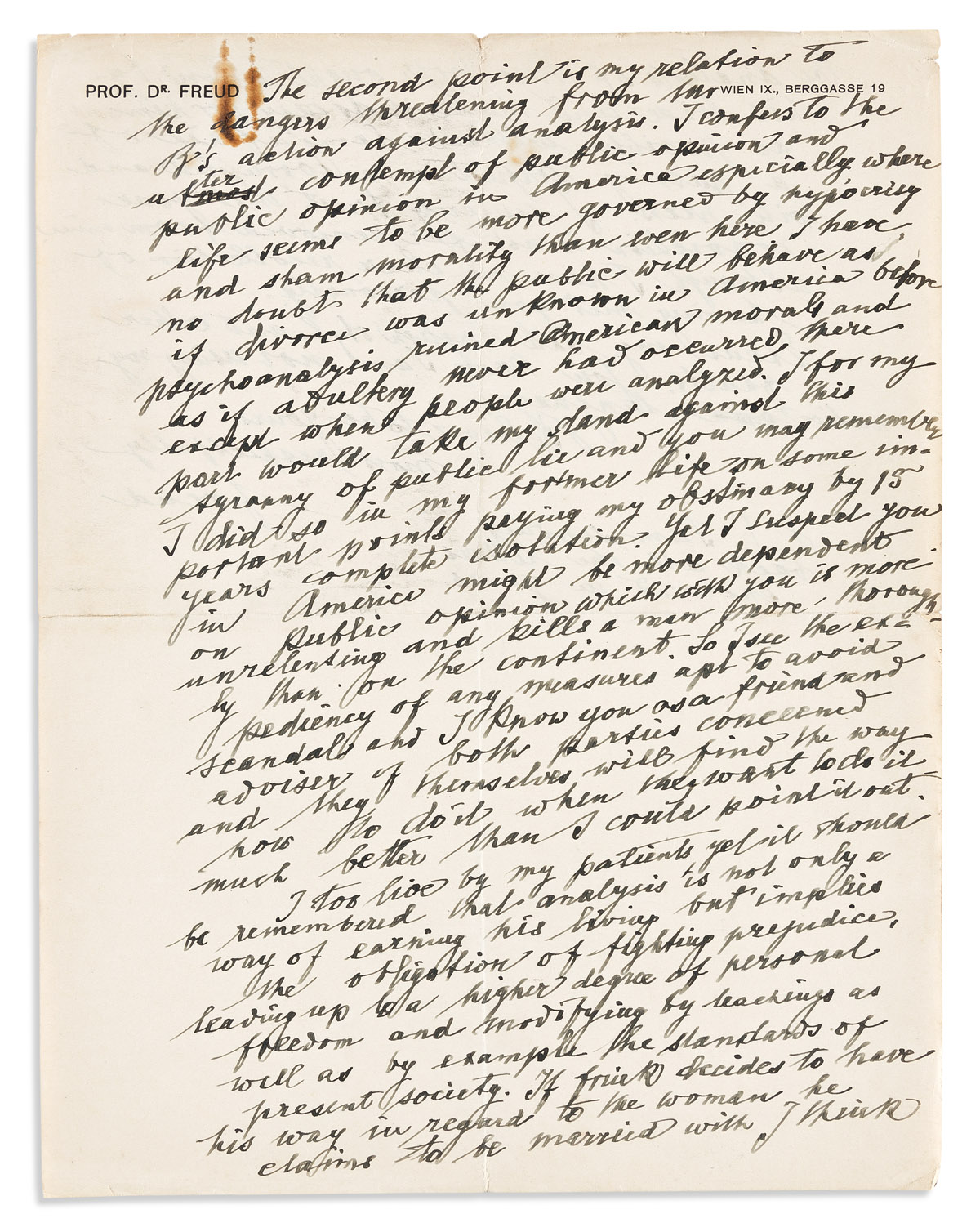

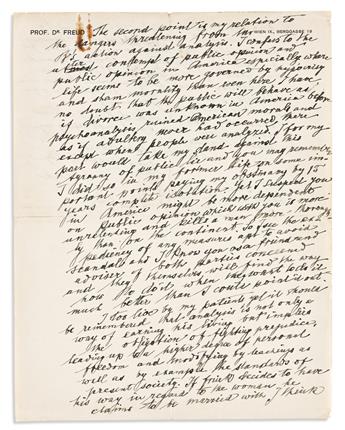

"The second point is my relation to the dangers threatening from Mr B's action against analysis. I confess to the utter contempt of public opinion and public opinion in America especially, where life seems to be more governed by hypocrisy and sham morality than even here. I have no doubt that the public will behave as if divorce was unknown in America before psychoanalysis ruined American morals and as if adultery never had occurred there except when people were analyzed. I for my part would take my stand against this tyranny of public lie and you may remember I did so in my former life on some important points paying [for] my obstinacy by 15 years complete isolation. Yet I suspect you in America might be more dependent on public opinion which with you is more unrelenting and kills a man more thoroughly than on the continent. So I see the expediency of any measures apt to avoid scandal . . . .

"I too live by my patients, yet it should be remembered that analysis is not only a way of earning his living but implies the obligation of fighting prejudice, leading up to a higher degree of personal freedom and modifying by teachings as well as by example the standards of present society. If Frink decides to have his way in regard to the woman he claims to be married with I think the analysis of New York ought to stand by his side and make it as easy for him as possible without being afraid of a passing tempest in a corrupted and vile press. . . ."

Horace Westlake Frink (1883-1936) was an American psychoanalyst and physician who co-founded the New York Psychoanalytic Society and who became Freud's professional representative in America until mental illness and scandal ended his career. Beginning in 1921, Frink struggled increasingly to maintain his mental health even as he practiced as an analyst, seeking treatment in sessions with Freud. Frink had fallen in love with one of his own patients, a married woman, Angelika Bijur, at a time when he himself was married. Frink's wife recognized that her husband's mental health was suffering and agreed to divorce him, expecting that marriage to Mrs. Bijur would help him. When Mr. Bijur learned of what had happened, he threatened Frink with a lawsuit for having violated the professionalism expected of an analyst. Because of Frink's connection to Freud, when the newspapers made the matter public, the scandal affected Freud's own reputation and his hopes for American psychoanalysis.

". . . As you are an analyst yourself I may trust you will not have thought it likely that I had acted as an advise-giver to Frink or Mrs B. You know it is not the passion of analysts to give out advise and to direct people in the line of our own preference. It is one of the distinguishing traits from the Jungians that we avoid doing so either in favour of ethics or in opposition to it. I simply had to read my patients mind and so I found out that he loved Mrs B., wanted her ardently and lacked the courage to confess it to himself. He struggled against a great many resistances, all of them . . . of an internal subjective psychological order. External difficulties did not come into consideration . . . .

"I had to explain to Frink what his internal difficulties were and did not deny that I thought it the good right of every human being to strive for sexual gratification and tender love if he saw a way to attain them, both of which he had not found with his wife. When he grew uncertain of his mind I had to take the side of his repressed desires and in this way became the advocate of his wish for divorce and marriage with Mrs B. In a conversation with the latter I felt entitled to guarantee the intensity and truthfulness of Frink's affection for her. I found her mind wavering too, but love for her husband played no part in the dilemma. She only doubted if Frink loved her really or deeply enough. So for me it was a case of honourable serious love versus convention, there my interest ended and the situation has not changed for me since then.

"Now I am quite aware that the public would not be able to grasp the difference between my real behaviour and my alleged advising both to divorce and to marry each other. But I hope you see it. From your letter I learn that the situation has changed indeed owing to a turn in Mr B's behaviour as his silly letter to me shows. I have no hold on this new practical side of the matter and have even less advise to offer than before . . . .

"The second point is my relation to the dangers threatening from Mr B's action against analysis. I confess to the utter contempt of public opinion and public opinion in America especially, where life seems to be more governed by hypocrisy and sham morality than even here. I have no doubt that the public will behave as if divorce was unknown in America before psychoanalysis ruined American morals and as if adultery never had occurred there except when people were analyzed. I for my part would take my stand against this tyranny of public lie and you may remember I did so in my former life on some important points paying [for] my obstinacy by 15 years complete isolation. Yet I suspect you in America might be more dependent on public opinion which with you is more unrelenting and kills a man more thoroughly than on the continent. So I see the expediency of any measures apt to avoid scandal . . . .

"I too live by my patients, yet it should be remembered that analysis is not only a way of earning his living but implies the obligation of fighting prejudice, leading up to a higher degree of personal freedom and modifying by teachings as well as by example the standards of present society. If Frink decides to have his way in regard to the woman he claims to be married with I think the analysis of New York ought to stand by his side and make it as easy for him as possible without being afraid of a passing tempest in a corrupted and vile press. . . ."

Horace Westlake Frink (1883-1936) was an American psychoanalyst and physician who co-founded the New York Psychoanalytic Society and who became Freud's professional representative in America until mental illness and scandal ended his career. Beginning in 1921, Frink struggled increasingly to maintain his mental health even as he practiced as an analyst, seeking treatment in sessions with Freud. Frink had fallen in love with one of his own patients, a married woman, Angelika Bijur, at a time when he himself was married. Frink's wife recognized that her husband's mental health was suffering and agreed to divorce him, expecting that marriage to Mrs. Bijur would help him. When Mr. Bijur learned of what had happened, he threatened Frink with a lawsuit for having violated the professionalism expected of an analyst. Because of Frink's connection to Freud, when the newspapers made the matter public, the scandal affected Freud's own reputation and his hopes for American psychoanalysis.

Exhibition Hours

Exhibition Hours

Aliquam vulputate ornare congue. Vestibulum maximus, libero in placerat faucibus, risus nisl molestie massa, ut maximus metus lectus vel lorem.