Sale 2697 - Lot 371

Price Realized: $ 5,200

Price Realized: $ 6,500

?Final Price Realized includes Buyer’s Premium added to Hammer Price

Estimate: $ 2,500 - $ 3,500

(SLAVERY.) Extensive letters discussing 3 enslaved people who had been loaned from North Carolina to Texas. 30 Autograph Letters Signed to Samuel M. Tate from his mother, cousin, and other parties, only 3 of them with integral address leaves and postal markings (none with stamps); sleeved in a binder, minimal wear. Various places, 1852-1856

Additional Details

These letters discuss the fate of three enslaved people who had been sent out on loan from Morganton, North Carolina to Galveston, Texas: Harriet, Mary, and Jim. The owners seem unusually concerned with Harriet in particular: her honor, her marriage prospects, and her well-being. Some hints suggest that she may have actually been a family member by blood. When Harriet was courted by a dark-skinned enslaved Texan man, her custodian suggested with enthusiasm: "It presents a very sure mode of stopping off the further undue increase of the white race."

Samuel McDowell Tate (1830-1897), the recipient of these letters, lived in the Appalachian town of Morganton, North Carolina, where he was a partner in a store; he later served as a lieutenant colonel in the Confederate army. The correspondence begins when he was only 22. Most of the letters are from his mother Susan Maria Tate (1809-1869), who claimed ownership of Harriet, Mary and Jim under somewhat vague and mysterious circumstances, but young Samuel had been tasked with managing them. The mother Susan had been born and raised in Pennsylvania, and had returned there after raising her family in North Carolina; these letters are written from the central Pennsylvania towns of Chambersburg, Marietta, and Ray's Hill. She was apparently rotating her residence among the homes of various extended family members.

As a town-dwelling shopkeeper, Samuel apparently had no immediate use for slaves. In 1852 and 1853, he hired them out to local families. Susan's letters to her son make the fate of the three enslaved people a primary concern. Typical is a 5 December 1852 letter: "Tell me how much you have let Gaithers have Harriet for this year. You surprise me when you tell me Mary is in the family way. I hope you have removed her from Jo. Free's. Remember she is very young to have children and she should be where she will be taken care of. For your own interest, I hope you will see that she is not neglected. I have no doubt she will make a more valuable negro than Harriet." On 30 July 1853, she wrote: "I am truly sorry Harriett has lost her child, but as you have observed it is the first one that has died which has been born ours."

In 1855, Samuel sent the three west to his successful older cousin Oliver Cromwell Hartley (1823-1858) of Galveston, Texas, whose mother was Susan's sister. Oliver was the official court reporter for the Texas Supreme Court; the state's Hartley County is named partly in his honor. Oliver kept Harriet as a personal servant, and hired out Mary and Jim to various local employers.

Samuel did not consult his mother before sending them to Texas, and she worried that they would suffer from exposure to the dangerous swampy coastal climate. She complained: "The Texas trip, I am thinking, was a poor one, and I exceeding regret those negroes were taken there, and am uneasy all the time about them. Oliver wrote to his mother some time ago that Harriett was quite discattisfyed" (19 August 1855). Susan planned to return South and wanted use of the family slaves as personal servants: "Now I want you to tell me why it is you have not sent or directed Oliver Hartley to send the negroes home. . . I hope you will not let them remain over another sickly season. I do not expect to live with Cora and have her furnish me a servant when I have of my own. . . . Now I think I have done so long without a servant that I am quite as able to have one as Mrs. Hartley" (21 February 1856).

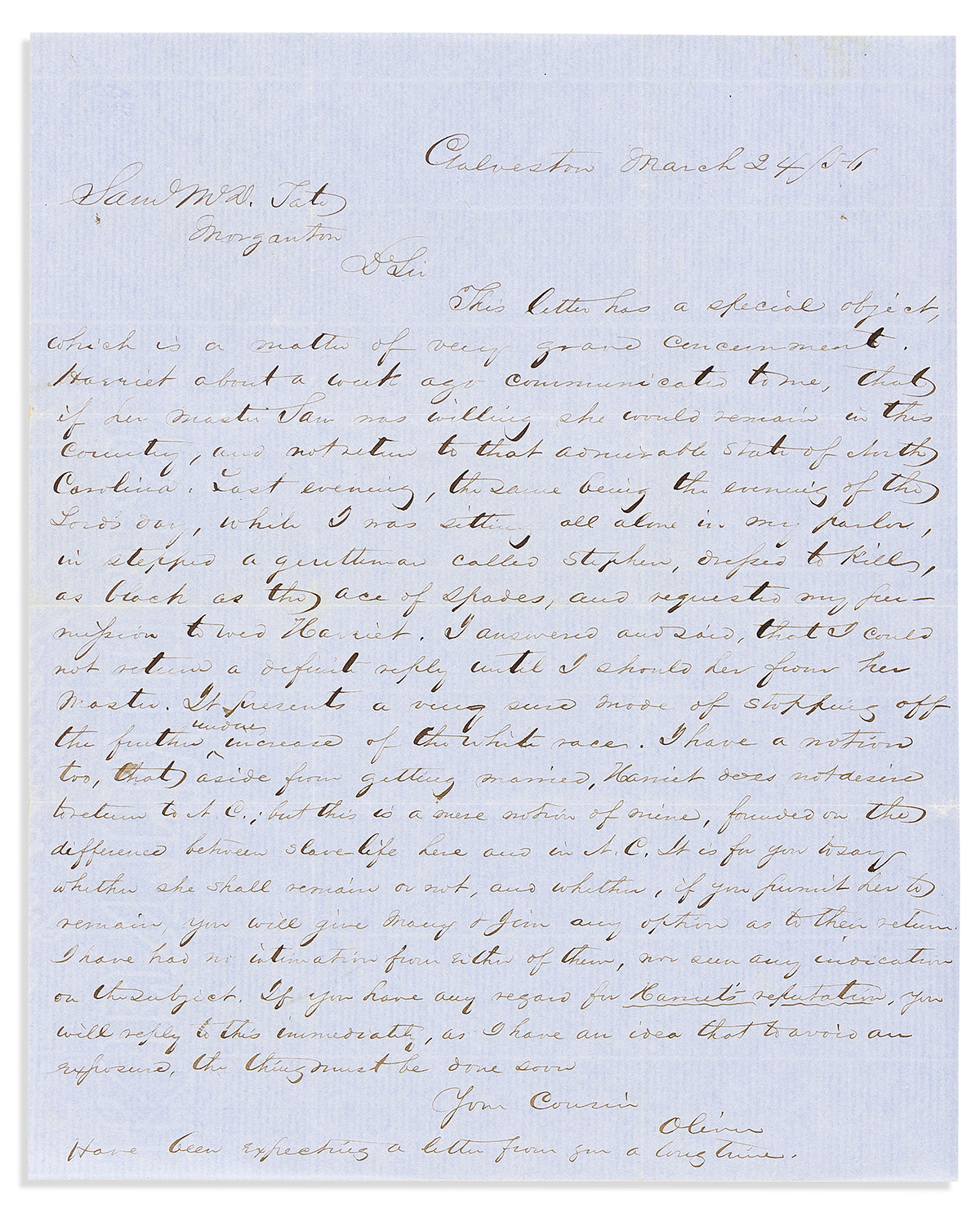

Cousin Oliver provided regular updates. Samuel soon desired to have the three sent back to North Carolina, but only if Harriet did not find a husband in Texas. On 25 November 1855, Oliver assured: "Harriett has no idea of getting married and remaining here. She will not get married therefore. Jim has been getting eight dollars a month for three months past. He could no doubt get more now, if it were likely that he would remain any time. Mary has a child, a boy about four weeks old." However, on 24 March 1856, Oliver wrote: "This letter has a special object, which is a matter of very grand concernment. Harriet about a week ago communicated to me that if her master Sam was willing, she would remain in this country, and not return to that admirable state of North Carolina. Last evening . . . while I was sitting all alone in my parlor, in stepped a gentleman called Stephen, dressed to kill, as black as the ace of spades, and requested my permission to wed Harriett. I answered and said that I could not return a definite reply until I should hear from her master. It presents a very sure mode of stopping off the further undue increase of the white race. . . . Aside from getting married, Harriett does not desire to return to N.C. . . . founded on the difference between slave life here and in N. C. . . . If you have any regard for Harriett's reputation you will reply to this immediately." Oliver added his support for the proposed union on 4 June: "You say nothing about buying Harriett's lover. If she were mine, I would rather than several hundred dollars, have her married to such a boy."

Susan got wind of this situation and emphasized to her son that she was the legal owner on 24 March 1856: "We will talk about the negroes. You say if they are my servants and at my death to belong to you and William, you will bring them home. Well you say you saw Major S. letter on that subject. If you cannot believe that you will not believe me, were I to tell you those were the conditions. . . . Who is to, or has received the hire of those negroes since they have been in Texas? . . . I want some comfort in a house of my own."

Susan wrote directly to Cousin Oliver, hoping for some answers, and he responded to her on 19 April: "Cousin Sam had always talked and written as if Harriet might stay here or not, as she pleased. . . . Harriett once before wrote to him on the subject, and his reply was that she might do as she pleased, but that if she got married she would have to stay here. He may have thought to frighten her off, but it has had a very contrary affect. She has had a taste of high negro life here, which is quite different from the same sphere in Morganton, I imagine; and then she has fallen in love with one of the best boys in town, who by the way is as black as the ace of spades. Under the impression that she could do as she pleased in the matter, she has come to think she could not live in N.C. at all, and that Texas is the greatest place in creation. Of course, neither Cousin Sam or I ever dreamed that it would interfere with your wishes. . . . I hope you will not be so cruel as to blight Harriett's prospects."

In Oliver's final letter on 26 December, he announces: "On the 23rd of November we sent Jim and Mary by Mr. Harwood of Texas, formerly of Virginia, with directions to leave them with the Mercantile House at Augusta, Ga. as directed by you. We handed Mr. Harwood $60 to pay their expenses. . . . Harriett and Em are well & well contented." Harriet remained behind in Galveston. We know nothing more of her fate.

Samuel McDowell Tate (1830-1897), the recipient of these letters, lived in the Appalachian town of Morganton, North Carolina, where he was a partner in a store; he later served as a lieutenant colonel in the Confederate army. The correspondence begins when he was only 22. Most of the letters are from his mother Susan Maria Tate (1809-1869), who claimed ownership of Harriet, Mary and Jim under somewhat vague and mysterious circumstances, but young Samuel had been tasked with managing them. The mother Susan had been born and raised in Pennsylvania, and had returned there after raising her family in North Carolina; these letters are written from the central Pennsylvania towns of Chambersburg, Marietta, and Ray's Hill. She was apparently rotating her residence among the homes of various extended family members.

As a town-dwelling shopkeeper, Samuel apparently had no immediate use for slaves. In 1852 and 1853, he hired them out to local families. Susan's letters to her son make the fate of the three enslaved people a primary concern. Typical is a 5 December 1852 letter: "Tell me how much you have let Gaithers have Harriet for this year. You surprise me when you tell me Mary is in the family way. I hope you have removed her from Jo. Free's. Remember she is very young to have children and she should be where she will be taken care of. For your own interest, I hope you will see that she is not neglected. I have no doubt she will make a more valuable negro than Harriet." On 30 July 1853, she wrote: "I am truly sorry Harriett has lost her child, but as you have observed it is the first one that has died which has been born ours."

In 1855, Samuel sent the three west to his successful older cousin Oliver Cromwell Hartley (1823-1858) of Galveston, Texas, whose mother was Susan's sister. Oliver was the official court reporter for the Texas Supreme Court; the state's Hartley County is named partly in his honor. Oliver kept Harriet as a personal servant, and hired out Mary and Jim to various local employers.

Samuel did not consult his mother before sending them to Texas, and she worried that they would suffer from exposure to the dangerous swampy coastal climate. She complained: "The Texas trip, I am thinking, was a poor one, and I exceeding regret those negroes were taken there, and am uneasy all the time about them. Oliver wrote to his mother some time ago that Harriett was quite discattisfyed" (19 August 1855). Susan planned to return South and wanted use of the family slaves as personal servants: "Now I want you to tell me why it is you have not sent or directed Oliver Hartley to send the negroes home. . . I hope you will not let them remain over another sickly season. I do not expect to live with Cora and have her furnish me a servant when I have of my own. . . . Now I think I have done so long without a servant that I am quite as able to have one as Mrs. Hartley" (21 February 1856).

Cousin Oliver provided regular updates. Samuel soon desired to have the three sent back to North Carolina, but only if Harriet did not find a husband in Texas. On 25 November 1855, Oliver assured: "Harriett has no idea of getting married and remaining here. She will not get married therefore. Jim has been getting eight dollars a month for three months past. He could no doubt get more now, if it were likely that he would remain any time. Mary has a child, a boy about four weeks old." However, on 24 March 1856, Oliver wrote: "This letter has a special object, which is a matter of very grand concernment. Harriet about a week ago communicated to me that if her master Sam was willing, she would remain in this country, and not return to that admirable state of North Carolina. Last evening . . . while I was sitting all alone in my parlor, in stepped a gentleman called Stephen, dressed to kill, as black as the ace of spades, and requested my permission to wed Harriett. I answered and said that I could not return a definite reply until I should hear from her master. It presents a very sure mode of stopping off the further undue increase of the white race. . . . Aside from getting married, Harriett does not desire to return to N.C. . . . founded on the difference between slave life here and in N. C. . . . If you have any regard for Harriett's reputation you will reply to this immediately." Oliver added his support for the proposed union on 4 June: "You say nothing about buying Harriett's lover. If she were mine, I would rather than several hundred dollars, have her married to such a boy."

Susan got wind of this situation and emphasized to her son that she was the legal owner on 24 March 1856: "We will talk about the negroes. You say if they are my servants and at my death to belong to you and William, you will bring them home. Well you say you saw Major S. letter on that subject. If you cannot believe that you will not believe me, were I to tell you those were the conditions. . . . Who is to, or has received the hire of those negroes since they have been in Texas? . . . I want some comfort in a house of my own."

Susan wrote directly to Cousin Oliver, hoping for some answers, and he responded to her on 19 April: "Cousin Sam had always talked and written as if Harriet might stay here or not, as she pleased. . . . Harriett once before wrote to him on the subject, and his reply was that she might do as she pleased, but that if she got married she would have to stay here. He may have thought to frighten her off, but it has had a very contrary affect. She has had a taste of high negro life here, which is quite different from the same sphere in Morganton, I imagine; and then she has fallen in love with one of the best boys in town, who by the way is as black as the ace of spades. Under the impression that she could do as she pleased in the matter, she has come to think she could not live in N.C. at all, and that Texas is the greatest place in creation. Of course, neither Cousin Sam or I ever dreamed that it would interfere with your wishes. . . . I hope you will not be so cruel as to blight Harriett's prospects."

In Oliver's final letter on 26 December, he announces: "On the 23rd of November we sent Jim and Mary by Mr. Harwood of Texas, formerly of Virginia, with directions to leave them with the Mercantile House at Augusta, Ga. as directed by you. We handed Mr. Harwood $60 to pay their expenses. . . . Harriett and Em are well & well contented." Harriet remained behind in Galveston. We know nothing more of her fate.

Exhibition Hours

Exhibition Hours

Aliquam vulputate ornare congue. Vestibulum maximus, libero in placerat faucibus, risus nisl molestie massa, ut maximus metus lectus vel lorem.