Sale 2663 - Lot 407

Unsold

Estimate: $ 7,000 - $ 10,000

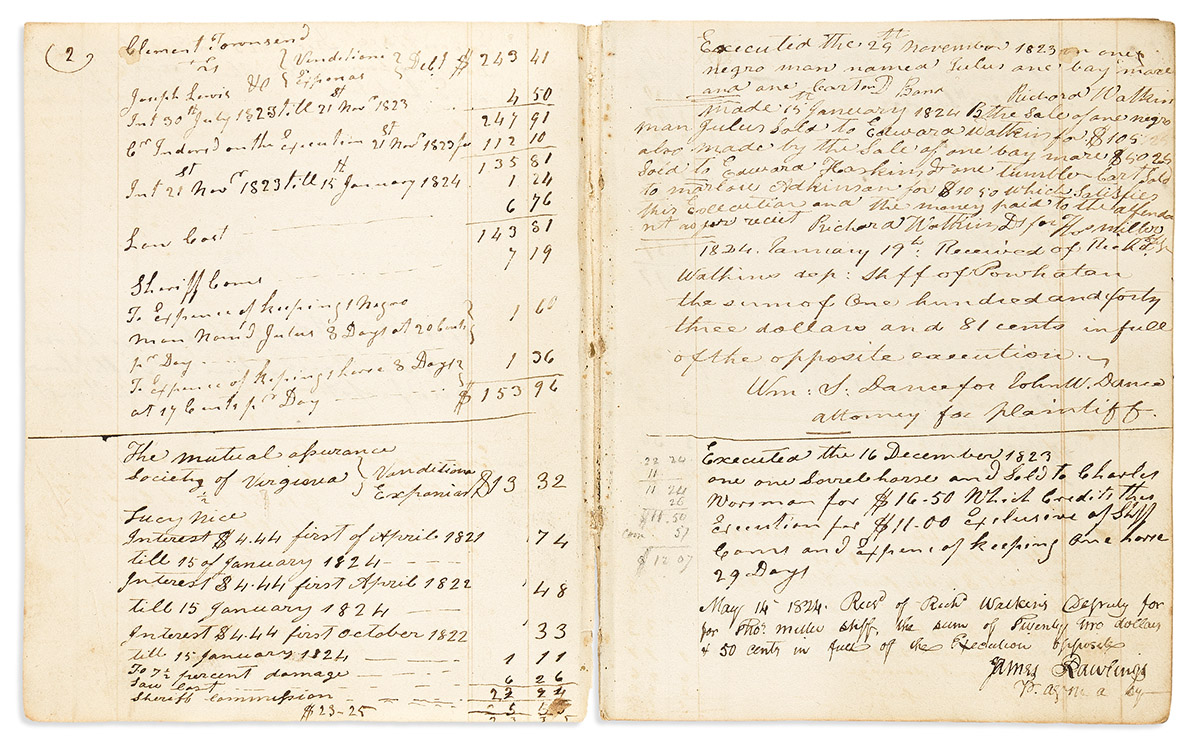

(SLAVERY.) Ledger of debt judgements collected by a Virginia deputy sheriff, including the transfer of dozens of enslaved people. [10], 194 double-sided manuscript leaves including index. Quarto, 7½ x 6¼ inches, worn original calf, mostly disbound with crude tape repair to backstrip; lacking at least the first leaf of the index and approximately 5 ledger leaves at end. Powhatan County, VA, December 1823 to February 1826

Additional Details

In the 19th century, the standard way of collecting an unpaid debt would be a court settlement. The sheriff or his deputy would then be authorized to come calling on the debtor and confiscate whatever was necessary to cover the debt and his own fees. In the antebellum plantation south, that often meant enslaved people.

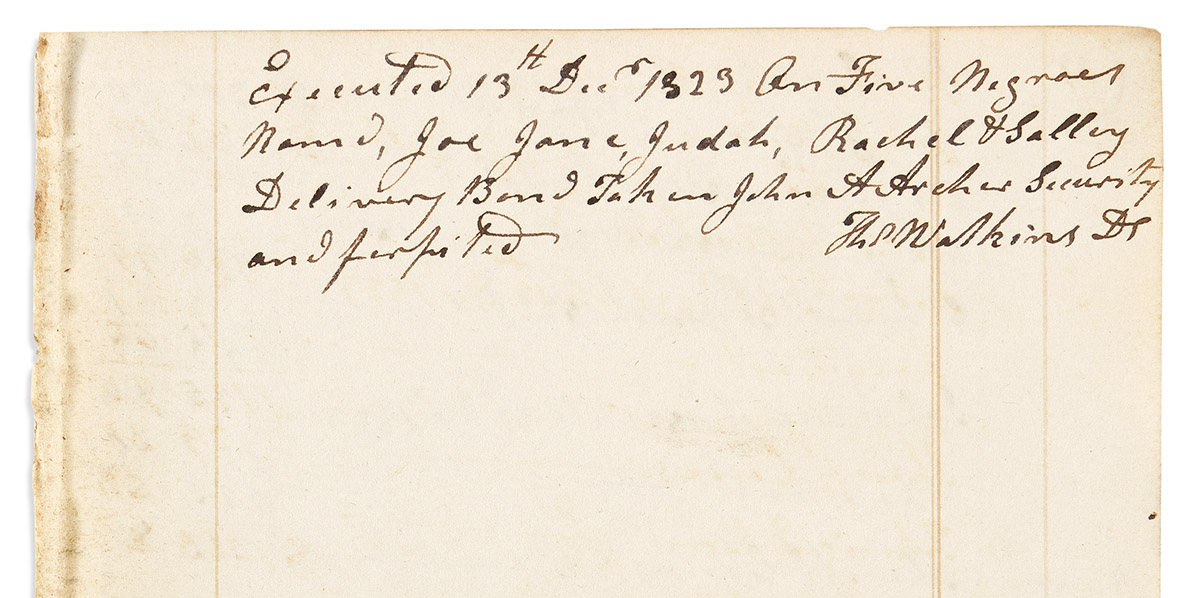

This ledger was kept by Thomas and Richard Watkins as deputy sheriffs of Powhatan County, VA not far west of Richmond. The deputies were assistants to Sheriff Thomas Miller, an elected official. The left side of the ledger records the judgment in a court case including the sheriff's personal fees and on the right side is the result of the execution. Sometimes a horse or household furniture would be seized; sometimes enslaved people would be seized to pay the judgment. For example, on page 11, as the result of a suit by John Wilder versus Peter F. Archer, Archer was ordered to pay $1045.87. The deputy arrived on 13 December 1823 and "executed . . . on five Negroes named Joe, Jane, Judah, Rachel & Salley." Similar actions involving enslaved people are recorded on pages 2, 12, 16, 21, 23, 24, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 40, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 49, 55, 78, 80, 94, 99, 100, 101, 106, 123, 137, 138, 150, 151, 155, and 170--dozens of men, women and children.

In one complex case in August 1824 involving debts against an estate going back ten years, the deputy "executed on two Negroes named Barcia and her child Salley and released because the plaintiff refused to indemnify"; the defendant was then billed $3.80 for "expence of keeping two Negroes" for almost three weeks (page 80).

In another case, the plaintiff filing the suit was "Rachel, a free Negro," who won a thirty-dollar judgement against one David Prattray. The law actually worked on Rachel's behalf here; the deputy secured the money and it was signed for by Rachel's attorney (page 146).

Among the noteworthy plaintiffs recorded here is Joseph Mayo, possibly the Civil War-era mayor of Richmond (pages 13, 95).

This ledger was kept by Thomas and Richard Watkins as deputy sheriffs of Powhatan County, VA not far west of Richmond. The deputies were assistants to Sheriff Thomas Miller, an elected official. The left side of the ledger records the judgment in a court case including the sheriff's personal fees and on the right side is the result of the execution. Sometimes a horse or household furniture would be seized; sometimes enslaved people would be seized to pay the judgment. For example, on page 11, as the result of a suit by John Wilder versus Peter F. Archer, Archer was ordered to pay $1045.87. The deputy arrived on 13 December 1823 and "executed . . . on five Negroes named Joe, Jane, Judah, Rachel & Salley." Similar actions involving enslaved people are recorded on pages 2, 12, 16, 21, 23, 24, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 40, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 49, 55, 78, 80, 94, 99, 100, 101, 106, 123, 137, 138, 150, 151, 155, and 170--dozens of men, women and children.

In one complex case in August 1824 involving debts against an estate going back ten years, the deputy "executed on two Negroes named Barcia and her child Salley and released because the plaintiff refused to indemnify"; the defendant was then billed $3.80 for "expence of keeping two Negroes" for almost three weeks (page 80).

In another case, the plaintiff filing the suit was "Rachel, a free Negro," who won a thirty-dollar judgement against one David Prattray. The law actually worked on Rachel's behalf here; the deputy secured the money and it was signed for by Rachel's attorney (page 146).

Among the noteworthy plaintiffs recorded here is Joseph Mayo, possibly the Civil War-era mayor of Richmond (pages 13, 95).

Exhibition Hours

Exhibition Hours

Aliquam vulputate ornare congue. Vestibulum maximus, libero in placerat faucibus, risus nisl molestie massa, ut maximus metus lectus vel lorem.