Sale 2598 - Lot 46

Price Realized: $ 5,800

Price Realized: $ 7,250

?Final Price Realized includes Buyer’s Premium added to Hammer Price

Estimate: $ 5,000 - $ 7,500

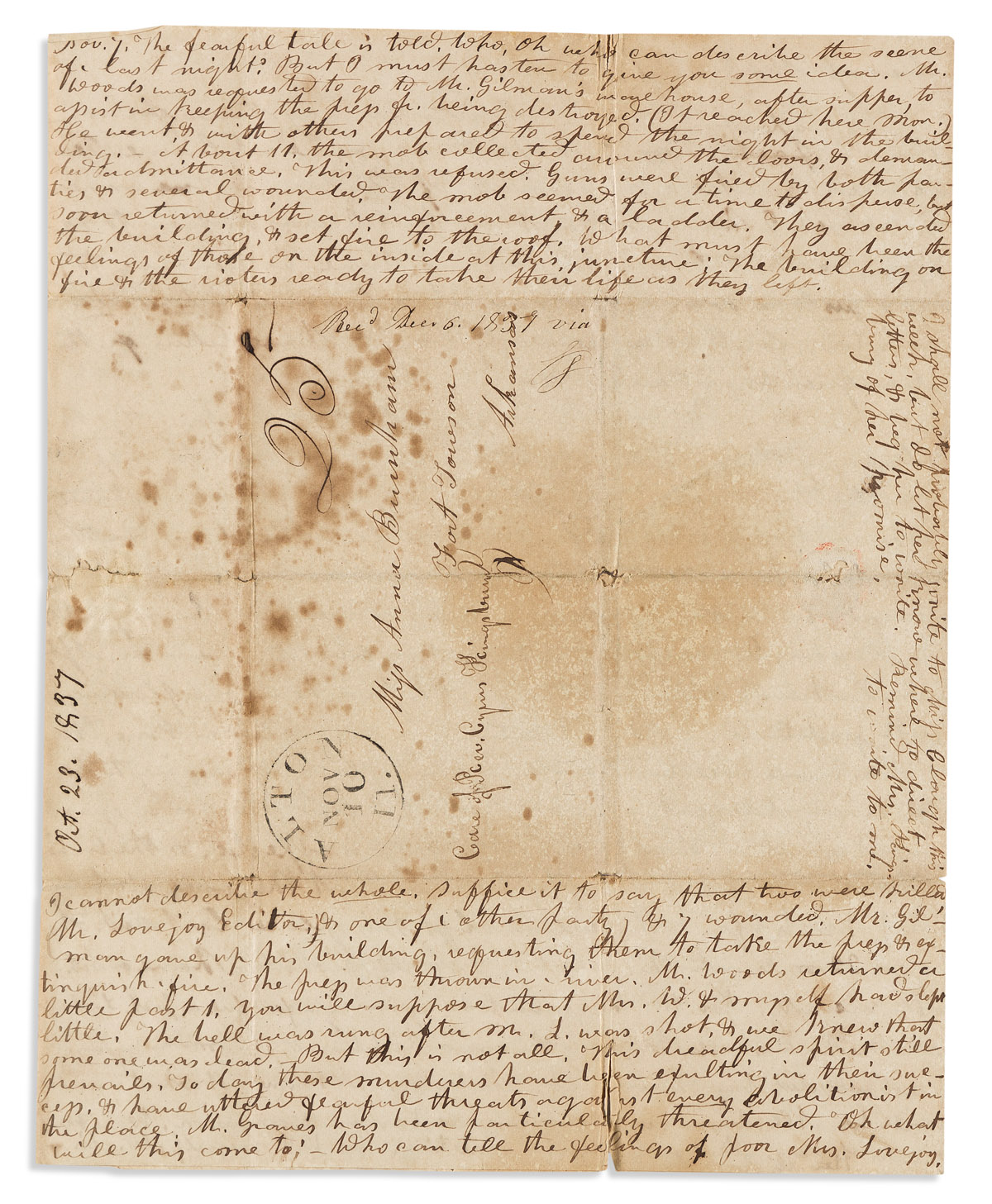

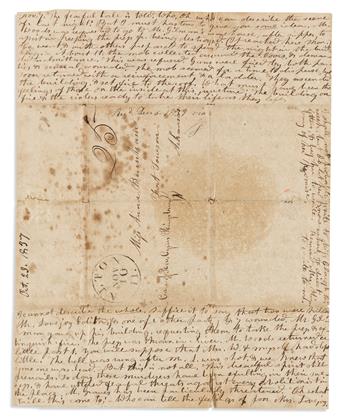

(SLAVERY & ABOLITION.) Elizabeth Ambrose Merrill. Letter describing the final days and death of abolitionist martyr Elijah Lovejoy. Autograph Letter Signed "E.A.M." to Miss Anna Burnham of Fort Towson. 4 pages, 9 3/4 x 7 3/4 inches, on one folding sheet, with address panel bearing an Alton postmark on the final page; foxing, moderate wear at intersection of folds. Alton, IL, 23 October to 8 November 1837

Additional Details

"He wept freely, but stated that it was not for himself those tears were shed."

In 1837, the abolitionist editor Elijah Parish Lovejoy began publishing the Alton Observer in Alton, Illinois, just across the river from slave-holding Missouri. On 7 November 1837, a pro-slavery mob stormed the warehouse where he printed the newspaper, killed Lovejoy, and threw his press into the river. His martyrdom was a seminal moment in the history of the abolition movement. Most notably, an obscure struggling entrepreneur named John Brown heard the news and announced "Here, before God, in the presence of these witnesses, from this time, I consecrate my life to the destruction of slavery!" Offered here is a contemporary first-hand account of the days leading up to Lovejoy's death, written by a sympathetic visitor to Alton.

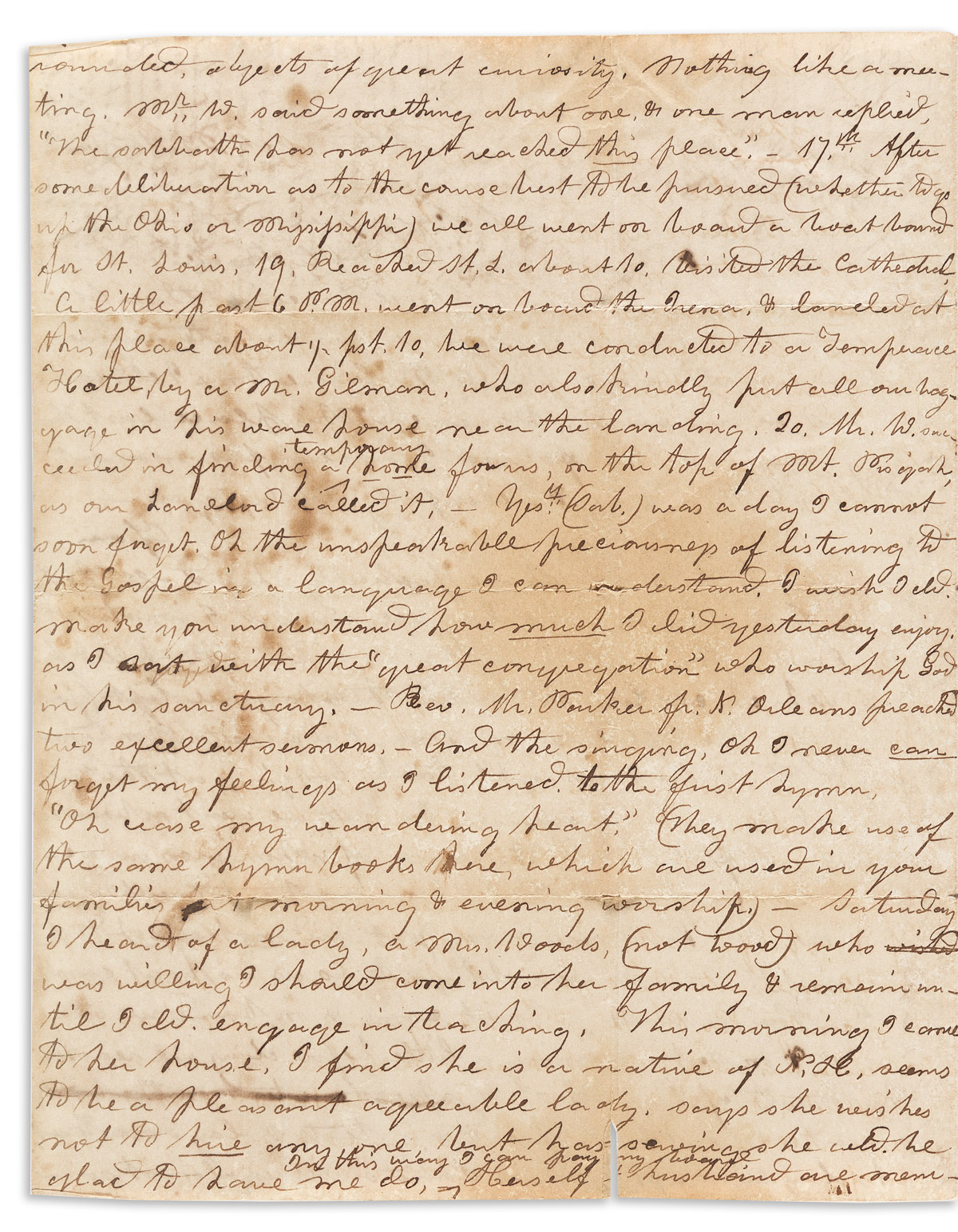

The letter's author Elizabeth Ambrose Merrill (1810-1868) was from New Hampshire, and went west as a missionary to the Choctaws in Eagletown, OK in 1835, accompanying the Rev. Cyrus Byington (who is mentioned at the end of this letter). She wrote to her friend Anna Burnham (1778-1847), a fellow missionary at Fort Towson a few miles west of Eagleton, who had been working with the Choctaws since the 1820s. Both women are listed as assistant missionaries to the Choctaws in the 1840 book "History of American Missions to the Heathen," page 340.

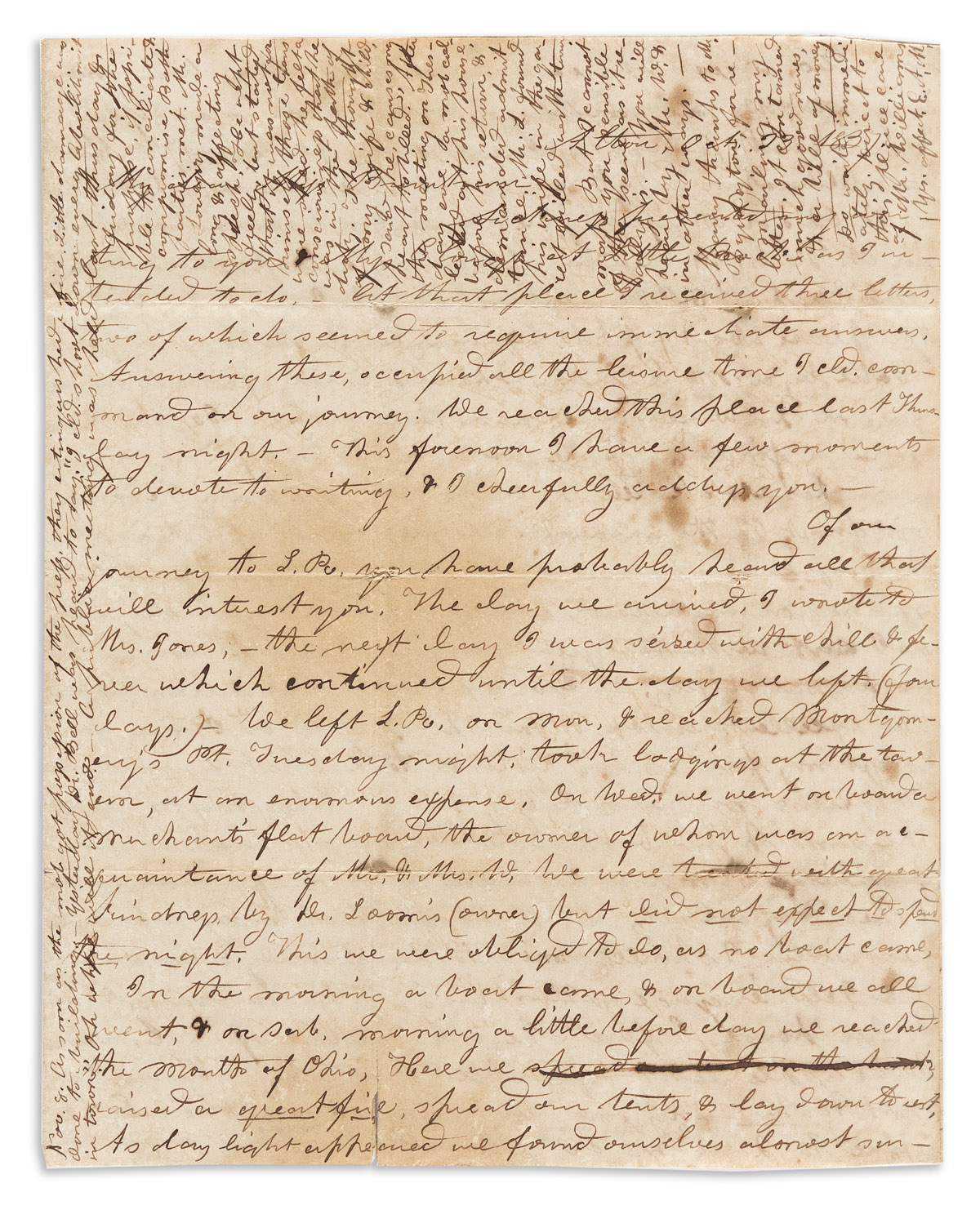

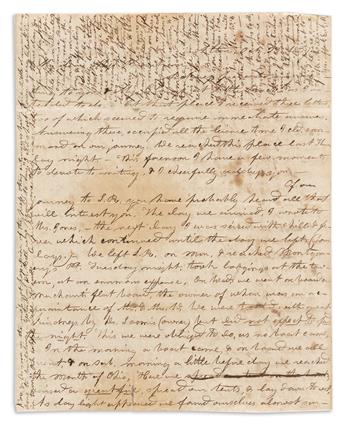

Merrill wrote this letter in 5 installments over a two-week period. It begins with her account of a trip eastward through Little Rock, AR to the Mississippi River, down to St. Louis, and then reaching Alton on 19 October, where she hopes to teach school. There she boards with J.C. Wood, who would be one of the final defenders of the Lovejoy press.

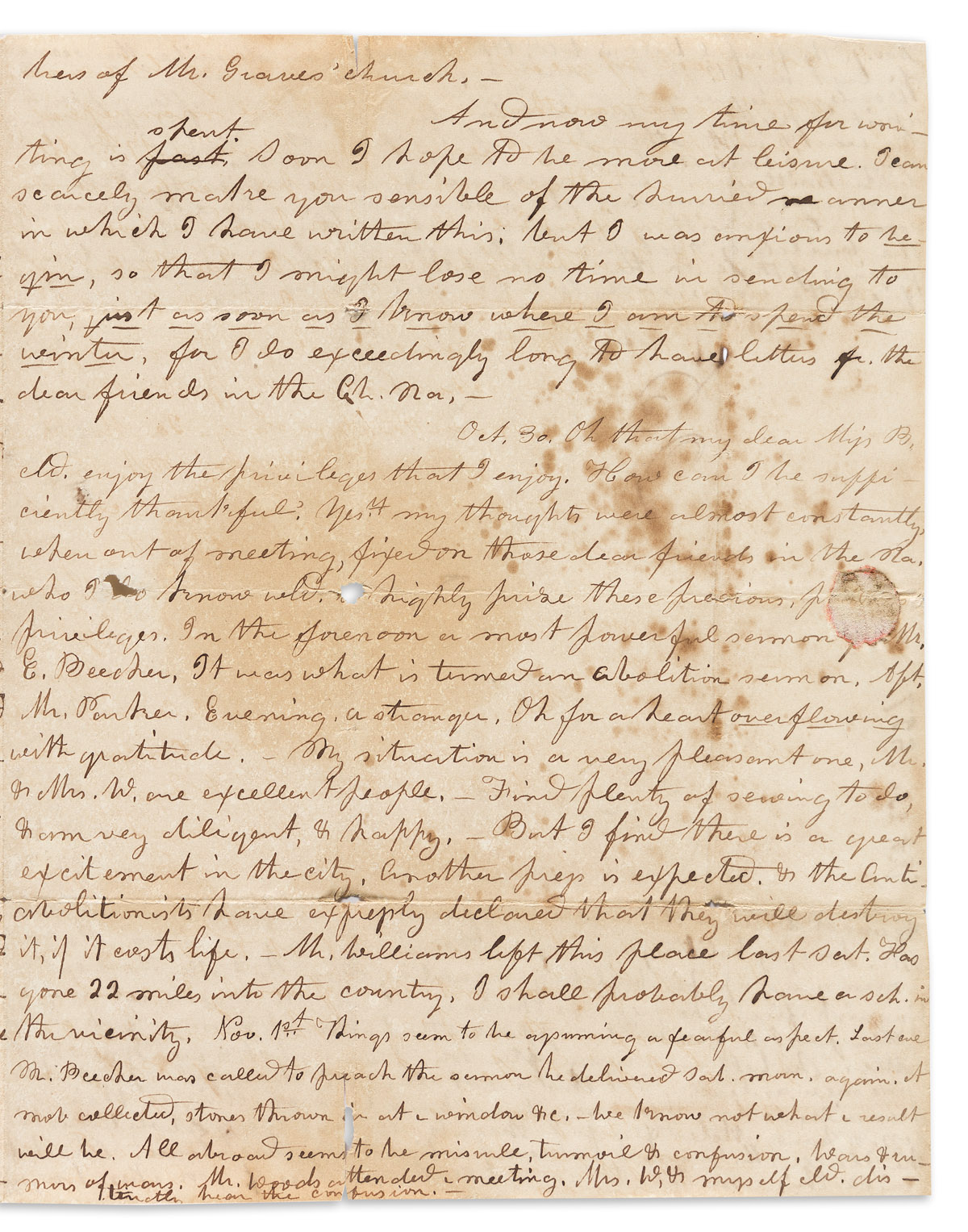

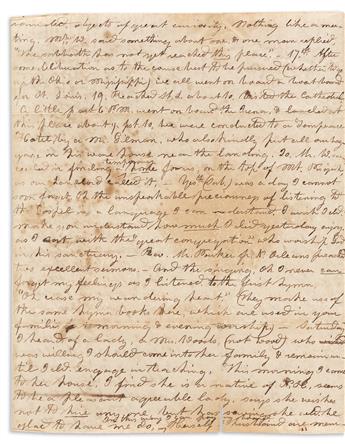

On 30 October she reports hearing a sermon by the Rev. Edward Beecher, the brother of Harriet Beecher Stowe and a close friend of Rev. Lovejoy's: "It was what is termed an abolitionist sermon. . . . I find there is a great excitement in the city. Another press is expected & the anti-abolitionists have expressly declared that they will destroy it, if it costs life."

The next day she reports "Things seem to be assuming a fearful aspect. Last eve Mr. Beecher was called to preach the sermon he delivered sab[bath] morn again. A mob collected, stones thrown in at the window &c. We know not what the result will be. All abroad seems to be misrule, turmoil & confusion. Wars & rumors of wars. Mr. Woods attended the meeting. Mrs. W. & myself c'ld distinctly hear the confusion."

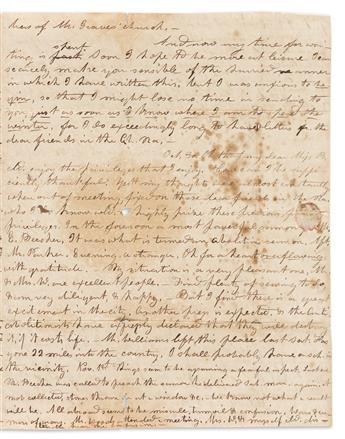

In a postscript, Merrill describes the events of the following days: "A public meeting was held last Thursday & Friday for the purpose, if possible, to conciliate & compromise. Both parties met. Mr. Lovejoy made a long & affecting speech. He wept freely, but stated that it was not for himself those tears were shed. He felt a consciousness that he was in the path of duty. The thought of my wife & child, said he, causes my heart to bleed. After the meeting on Tuesday eve., a mob collected at his house before his return & demanded admittance. Mr. L. found his wife in the garret filled with terror."

On the day of the mob attack, 7 November, Merrill wrote: "The fearful tale is told. Who, oh who, can describe the scene of last night? But I must hasten to give you some idea. Mr. Woods was requested to go to Mr. Gilman's warehouse, after supper, to assist in keeping the press fr. being destroyed. (It reached here Mon.). He went, & with others prepared to spend the night in the building. About 11, the mob collected around the doors, & demanded admittance. This was refused. Guns were fired by both parties & several wounded. The mob seemed for a time to disperse, but soon returned with a reinforcement & a ladder. They ascended the building, & set fire to the roof. What must have been the feelings of those on the inside at this juncture: the building on fire & the rioters ready to take their life as they left. I cannot describe the whole, suffice it to say that two were killed: Mr. Lovejoy, editor & one of the other party, & 7 wounded. Mr. Gilman gave up his building, requesting them to take the press & extinguish the fire. The press was thrown in the river. Mr. Woods returned a little past 1. You will suppose that Mrs. W. & myself had slept little. The bell was rung after Mr. L. was shot, & we knew that someone was dead. But this is not all. This dreadful spirit still prevails. Today these murderers have been exulting in their success & have uttered fearful threats against every abolitionist in the place. Mr. Graves has been particularly threatened. Oh, what will this come to! Who can tell the feelings of poor Mrs. Lovejoy?"

Merrill added one final addendum the day after the riot, writing crosswise on the first page to add: "As soon as the mob got possession of the press they extinguished the fire. Little damage was done to the building. Yesterday Dr. Bell was heard to say. 'I c'ld shoot down every abolitionist in town'. Oh, where will it end?"

Printed accounts of Lovejoy's murder swept across the country in the following months, but we have traced no manuscripts at auction relating to these fateful events, and certainly none with this high level of emotion and detail.

In 1837, the abolitionist editor Elijah Parish Lovejoy began publishing the Alton Observer in Alton, Illinois, just across the river from slave-holding Missouri. On 7 November 1837, a pro-slavery mob stormed the warehouse where he printed the newspaper, killed Lovejoy, and threw his press into the river. His martyrdom was a seminal moment in the history of the abolition movement. Most notably, an obscure struggling entrepreneur named John Brown heard the news and announced "Here, before God, in the presence of these witnesses, from this time, I consecrate my life to the destruction of slavery!" Offered here is a contemporary first-hand account of the days leading up to Lovejoy's death, written by a sympathetic visitor to Alton.

The letter's author Elizabeth Ambrose Merrill (1810-1868) was from New Hampshire, and went west as a missionary to the Choctaws in Eagletown, OK in 1835, accompanying the Rev. Cyrus Byington (who is mentioned at the end of this letter). She wrote to her friend Anna Burnham (1778-1847), a fellow missionary at Fort Towson a few miles west of Eagleton, who had been working with the Choctaws since the 1820s. Both women are listed as assistant missionaries to the Choctaws in the 1840 book "History of American Missions to the Heathen," page 340.

Merrill wrote this letter in 5 installments over a two-week period. It begins with her account of a trip eastward through Little Rock, AR to the Mississippi River, down to St. Louis, and then reaching Alton on 19 October, where she hopes to teach school. There she boards with J.C. Wood, who would be one of the final defenders of the Lovejoy press.

On 30 October she reports hearing a sermon by the Rev. Edward Beecher, the brother of Harriet Beecher Stowe and a close friend of Rev. Lovejoy's: "It was what is termed an abolitionist sermon. . . . I find there is a great excitement in the city. Another press is expected & the anti-abolitionists have expressly declared that they will destroy it, if it costs life."

The next day she reports "Things seem to be assuming a fearful aspect. Last eve Mr. Beecher was called to preach the sermon he delivered sab[bath] morn again. A mob collected, stones thrown in at the window &c. We know not what the result will be. All abroad seems to be misrule, turmoil & confusion. Wars & rumors of wars. Mr. Woods attended the meeting. Mrs. W. & myself c'ld distinctly hear the confusion."

In a postscript, Merrill describes the events of the following days: "A public meeting was held last Thursday & Friday for the purpose, if possible, to conciliate & compromise. Both parties met. Mr. Lovejoy made a long & affecting speech. He wept freely, but stated that it was not for himself those tears were shed. He felt a consciousness that he was in the path of duty. The thought of my wife & child, said he, causes my heart to bleed. After the meeting on Tuesday eve., a mob collected at his house before his return & demanded admittance. Mr. L. found his wife in the garret filled with terror."

On the day of the mob attack, 7 November, Merrill wrote: "The fearful tale is told. Who, oh who, can describe the scene of last night? But I must hasten to give you some idea. Mr. Woods was requested to go to Mr. Gilman's warehouse, after supper, to assist in keeping the press fr. being destroyed. (It reached here Mon.). He went, & with others prepared to spend the night in the building. About 11, the mob collected around the doors, & demanded admittance. This was refused. Guns were fired by both parties & several wounded. The mob seemed for a time to disperse, but soon returned with a reinforcement & a ladder. They ascended the building, & set fire to the roof. What must have been the feelings of those on the inside at this juncture: the building on fire & the rioters ready to take their life as they left. I cannot describe the whole, suffice it to say that two were killed: Mr. Lovejoy, editor & one of the other party, & 7 wounded. Mr. Gilman gave up his building, requesting them to take the press & extinguish the fire. The press was thrown in the river. Mr. Woods returned a little past 1. You will suppose that Mrs. W. & myself had slept little. The bell was rung after Mr. L. was shot, & we knew that someone was dead. But this is not all. This dreadful spirit still prevails. Today these murderers have been exulting in their success & have uttered fearful threats against every abolitionist in the place. Mr. Graves has been particularly threatened. Oh, what will this come to! Who can tell the feelings of poor Mrs. Lovejoy?"

Merrill added one final addendum the day after the riot, writing crosswise on the first page to add: "As soon as the mob got possession of the press they extinguished the fire. Little damage was done to the building. Yesterday Dr. Bell was heard to say. 'I c'ld shoot down every abolitionist in town'. Oh, where will it end?"

Printed accounts of Lovejoy's murder swept across the country in the following months, but we have traced no manuscripts at auction relating to these fateful events, and certainly none with this high level of emotion and detail.

Exhibition Hours

Exhibition Hours

Aliquam vulputate ornare congue. Vestibulum maximus, libero in placerat faucibus, risus nisl molestie massa, ut maximus metus lectus vel lorem.