Sale 2471 - Lot 29

Price Realized: $ 7,500

Price Realized: $ 9,375

?Final Price Realized includes Buyer’s Premium added to Hammer Price

Estimate: $ 10,000 - $ 15,000

(SLAVERY AND ABOLITION.) Papers of an early Pennsylvania abolitionist, including the landmark kidnapping case of John Davis. 7 manuscript documents and one printed circular, various sizes up to 16 inches in length; generally minor wear and a few tasteful repairs; handsomely housed in a modern 1/4 morocco folding case. Vp, 1791-1800

Additional Details

These are the papers of David Redick (1750-1805) of Washington, a small town in western Pennsylvania near the Ohio frontier. Redick was one of the founders of the small Washington Abolition Society in 1789, and remained active as a lone fighter for the cause even after his local group disbanded in 1795. He was also a member, remotely, of the much larger Pennsylvania abolition society, which was based hundreds of miles to the east. See Oldfield, "Transatlantic Abolitionism," pages 24 and 115-6.

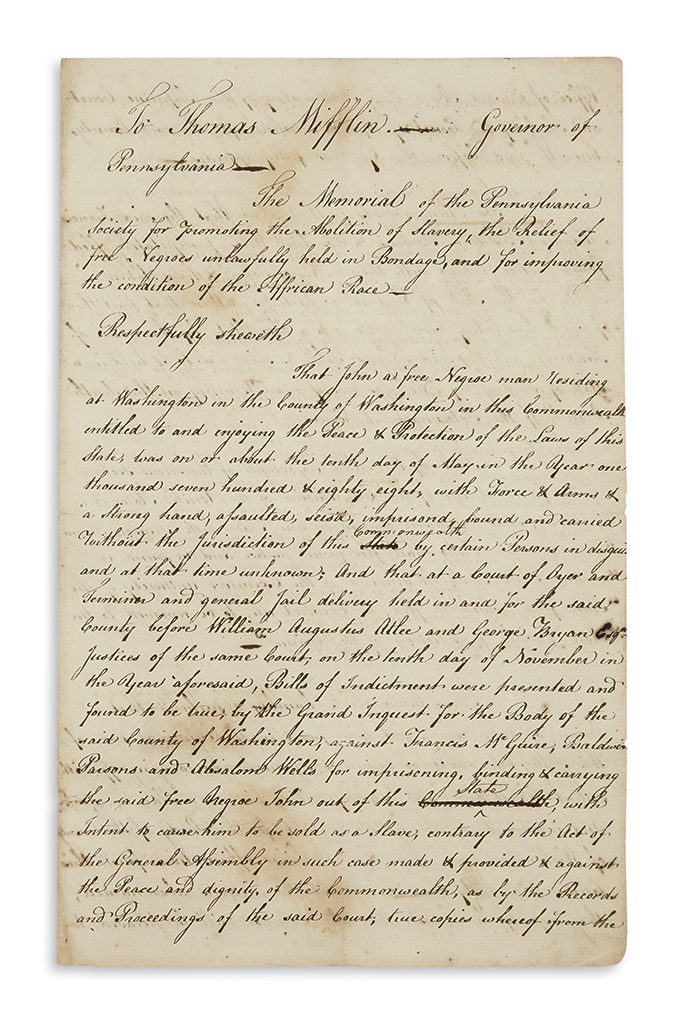

Most important in this lot are 3 folio documents regarding the Washington Abolition Society's involvement in an important legal case. John Davis was born into slavery in Maryland, and in the 1770s was brought to a frontier farm in what became Pennsylvania. Under the state's gradual emancipation law, he became legally free in 1782 when his owner failed to register him. The owner then sent him to Virginia, some Pennsylvania abolitionists followed and liberated him, and then a team of three Virginians went north to Pennsylvania to recapture him, then selling him to a new owner. Offered in this lot are: 1) Manuscript Letter Signed by William Rogers as vice president of the Pennsylvania abolition society to the Washington society. The larger society defends themselves against apparent accusations that they were ignoring the John Davis case--"having already exerted ourselves for his deliverance, and being willing to repeat our exertions, on a rational prospect of success, in any way consistant with the urgent and sometimes expensive claims of others upon our care and protection." They forward the minutes of their meetings, and a copy of their letter to the governor, to prove their due diligence. They conclude with reflections on the good work being done by abolitionists: "We rejoice, however, that a few of those whom you have restored to the exercise of their natural rights and capacities justify the interposition of providence in their behalf. We think this is a sufficient reward for the labour bestowed upon them all. . . . We have formed committees upon the plan for the improvement of the Free Blacks." They pledge to continue their work "untill it terminates (as we trust it will) with the approbation of heaven and our country, in the final abolition of slavery." Philadelphia, 23 June 1791 2) Letter from the Pennsylvania abolition society to Governor Thomas Mifflin, recounting the Davis case and asserting that "a crime of deeper dye is not to be found in the criminal code of this state, than that of taking a freeman and carrying him off with intent to sell him, and actually selling him as a slave." Retained manuscript copy, 5 May 1790. 3) An early manuscript abstract of the minutes of the Pennsylvania abolition society, tracing their efforts to "devise some mode to get Negro John once more within the limits of this state," 1788-1790. These minutes name David Redick as the one who brought the case to the attention of the society. These minutes (and the letter to the governor) were apparently enclosures with the 23 June 1791 letter.

The John Davis story had quite an unhappy ending. The abolitionists succeeded in getting the attention of Governor Mifflin, who wrote a stern letter to the governor of Virginia demanding the return of Davis and extradition of his captors. This set into motion a defensive movement by southern congressmen, who were able to secure the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793. Davis remained in slavery in Virginia for the rest of his life, and the law hindered other efforts to assist captured freemen.

Also included are 4 other manuscripts from Redick's career as an abolitionist. On the face, they seem to suggest his financial involvement in the sale of slaves. However, it appears that they relate to Pennsylvania's law requiring a surety bond for any slave given their freedom. The first case is of a "negro wench named Kate." This lot includes a bond from a Virginia woman to James Pemberton of the Pennsylvania abolition society "that if the above bound Janet Prather shall will and honestly give bonds with ample and sufficient security living in the State of Pennsylvania to David Redick Esq. member of the Abolition Society within three months from the date hereof, for the fulfillment and complete execution of this indenture given her by a negro woman Kate on herself and two of her children," 23 April 1796. It is followed by an 8 June 1798 letter from a Jonathan Davis of Morgantown, WV to Redick about this same family: "The remainder of their time is to be disposed of, and as I believe that Kate would prefer living in Washington, I have taken leave to request that you will inform me by next post whether any person there would be likely to want her. . . . Kate has yet three years of her time to serve and the children until of age. I think that she is well worth £50 currency with her children." Apparently Redick had posted Kate's surety bonds and she lived in a state of temporary indentured servitude to pay off her debt, at which point Redick was charged with finding employment for her in his home town. The other case was Peggy Kuntz, whose race is not given. The lot includes two receipts relating to her release from indentured servitude, 15 April and 15 June 1800. The first is docketed "Pegg Kuntz's rct for freedom": "I have this day received twelve dollars for the residue of my freedom except the bed which with the approbation of my brother I have recd." Two months later, she signed for the bed and bedding, with an "X." This would seem to be a similar case to "Negro Kate," a woman leaving indentured servitude with Redick's assistance.

Also included is Redick's copy of a printed circular letter from the Pennsylvania abolition society, seeking a census of African-Americans in Pennsylvania (slave and free). It is signed in type by Edward Garrigues and others and dated 30 May 1796. It is worn with water damage on the address panel. We have traced no copies in OCLC, ESTC, or elsewhere. As a whole, these eight documents tell the story of a dedicated worker for abolition on Pennsylvania's western frontier, including his pivotal involvement in the tragic John Davis case.

Most important in this lot are 3 folio documents regarding the Washington Abolition Society's involvement in an important legal case. John Davis was born into slavery in Maryland, and in the 1770s was brought to a frontier farm in what became Pennsylvania. Under the state's gradual emancipation law, he became legally free in 1782 when his owner failed to register him. The owner then sent him to Virginia, some Pennsylvania abolitionists followed and liberated him, and then a team of three Virginians went north to Pennsylvania to recapture him, then selling him to a new owner. Offered in this lot are: 1) Manuscript Letter Signed by William Rogers as vice president of the Pennsylvania abolition society to the Washington society. The larger society defends themselves against apparent accusations that they were ignoring the John Davis case--"having already exerted ourselves for his deliverance, and being willing to repeat our exertions, on a rational prospect of success, in any way consistant with the urgent and sometimes expensive claims of others upon our care and protection." They forward the minutes of their meetings, and a copy of their letter to the governor, to prove their due diligence. They conclude with reflections on the good work being done by abolitionists: "We rejoice, however, that a few of those whom you have restored to the exercise of their natural rights and capacities justify the interposition of providence in their behalf. We think this is a sufficient reward for the labour bestowed upon them all. . . . We have formed committees upon the plan for the improvement of the Free Blacks." They pledge to continue their work "untill it terminates (as we trust it will) with the approbation of heaven and our country, in the final abolition of slavery." Philadelphia, 23 June 1791 2) Letter from the Pennsylvania abolition society to Governor Thomas Mifflin, recounting the Davis case and asserting that "a crime of deeper dye is not to be found in the criminal code of this state, than that of taking a freeman and carrying him off with intent to sell him, and actually selling him as a slave." Retained manuscript copy, 5 May 1790. 3) An early manuscript abstract of the minutes of the Pennsylvania abolition society, tracing their efforts to "devise some mode to get Negro John once more within the limits of this state," 1788-1790. These minutes name David Redick as the one who brought the case to the attention of the society. These minutes (and the letter to the governor) were apparently enclosures with the 23 June 1791 letter.

The John Davis story had quite an unhappy ending. The abolitionists succeeded in getting the attention of Governor Mifflin, who wrote a stern letter to the governor of Virginia demanding the return of Davis and extradition of his captors. This set into motion a defensive movement by southern congressmen, who were able to secure the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793. Davis remained in slavery in Virginia for the rest of his life, and the law hindered other efforts to assist captured freemen.

Also included are 4 other manuscripts from Redick's career as an abolitionist. On the face, they seem to suggest his financial involvement in the sale of slaves. However, it appears that they relate to Pennsylvania's law requiring a surety bond for any slave given their freedom. The first case is of a "negro wench named Kate." This lot includes a bond from a Virginia woman to James Pemberton of the Pennsylvania abolition society "that if the above bound Janet Prather shall will and honestly give bonds with ample and sufficient security living in the State of Pennsylvania to David Redick Esq. member of the Abolition Society within three months from the date hereof, for the fulfillment and complete execution of this indenture given her by a negro woman Kate on herself and two of her children," 23 April 1796. It is followed by an 8 June 1798 letter from a Jonathan Davis of Morgantown, WV to Redick about this same family: "The remainder of their time is to be disposed of, and as I believe that Kate would prefer living in Washington, I have taken leave to request that you will inform me by next post whether any person there would be likely to want her. . . . Kate has yet three years of her time to serve and the children until of age. I think that she is well worth £50 currency with her children." Apparently Redick had posted Kate's surety bonds and she lived in a state of temporary indentured servitude to pay off her debt, at which point Redick was charged with finding employment for her in his home town. The other case was Peggy Kuntz, whose race is not given. The lot includes two receipts relating to her release from indentured servitude, 15 April and 15 June 1800. The first is docketed "Pegg Kuntz's rct for freedom": "I have this day received twelve dollars for the residue of my freedom except the bed which with the approbation of my brother I have recd." Two months later, she signed for the bed and bedding, with an "X." This would seem to be a similar case to "Negro Kate," a woman leaving indentured servitude with Redick's assistance.

Also included is Redick's copy of a printed circular letter from the Pennsylvania abolition society, seeking a census of African-Americans in Pennsylvania (slave and free). It is signed in type by Edward Garrigues and others and dated 30 May 1796. It is worn with water damage on the address panel. We have traced no copies in OCLC, ESTC, or elsewhere. As a whole, these eight documents tell the story of a dedicated worker for abolition on Pennsylvania's western frontier, including his pivotal involvement in the tragic John Davis case.

Exhibition Hours

Exhibition Hours

Aliquam vulputate ornare congue. Vestibulum maximus, libero in placerat faucibus, risus nisl molestie massa, ut maximus metus lectus vel lorem.