Sale 2517 - Lot 204

Price Realized: $ 140,000

Price Realized: $ 173,000

?Final Price Realized includes Buyer’s Premium added to Hammer Price

Estimate: $ 80,000 - $ 120,000

INCLUDING NUMEROUS CONNECTIONS TO BOOKER T. WASHINGTON'S FAMILY (SLAVERY AND ABOLITION.) Records of the Dickinson & Shrewsbury salt works, including extensive slave labor correspondence. More than 2000 items in 4 boxes (4 linear feet), consisting mostly of correspondence, plus some memorandum books, receipts, legal records, and a very small quantity of printed ephemera. Kanawha Salines, WV and vp, 1801-1908 (bulk 1820-65)

Additional Details

The Dickinson & Shrewsbury salt works in West Virginia was a large operation. This substantial archive of their business records and correspondence is important in three ways. First, for its thorough documentation of a large industrial enterprise in a time and place and industry which are rarely studied. Second, for the literally thousands of documents relating to the enslaved people who operated its furnaces and wagons. Finally, for the plant's numerous connections to Booker T. Washington, who lived near the salt works after abolition.

The key figures in this archive are William Dickinson (1772-1861) and his brother-in-law Joel Shrewsbury (1779-1859), the founding partners of the firm of Dickinson & Shrewsbury. They began as tobacco merchants in Bedford County, VA. In the winter of 1814-15 they moved west of the Appalachian Mountains to Kanawha County, and acquired land in the Kanawha Salines region north of Charlestown (now the town of Malden). They began their salt-making operation in earnest in 1818, tapping into the remnants of an underwater ocean and using furnaces to boil off the salty water into a marketable product. William Dickinson Jr. (1798-1881) became active in the business by the 1830s. By the 1850s, grandsons Henry C. Dickinson (1830-1871) and John Q. Dickinson (1831-1925) were also playing active roles. The Shrewsbury & Dickinson partnership became acrimonious by 1857, with a messy lawsuit ending in the firm's dissolution in 1861; John Q. Dickinson led the salt works after the war. See Stealy, "Virginia's Mercantile-Manufacturing Frontier: Dickinson & Shrewsbury and the Great Kanawha Salt Industry," in The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 101:4 (October 1993), pages 509-534.

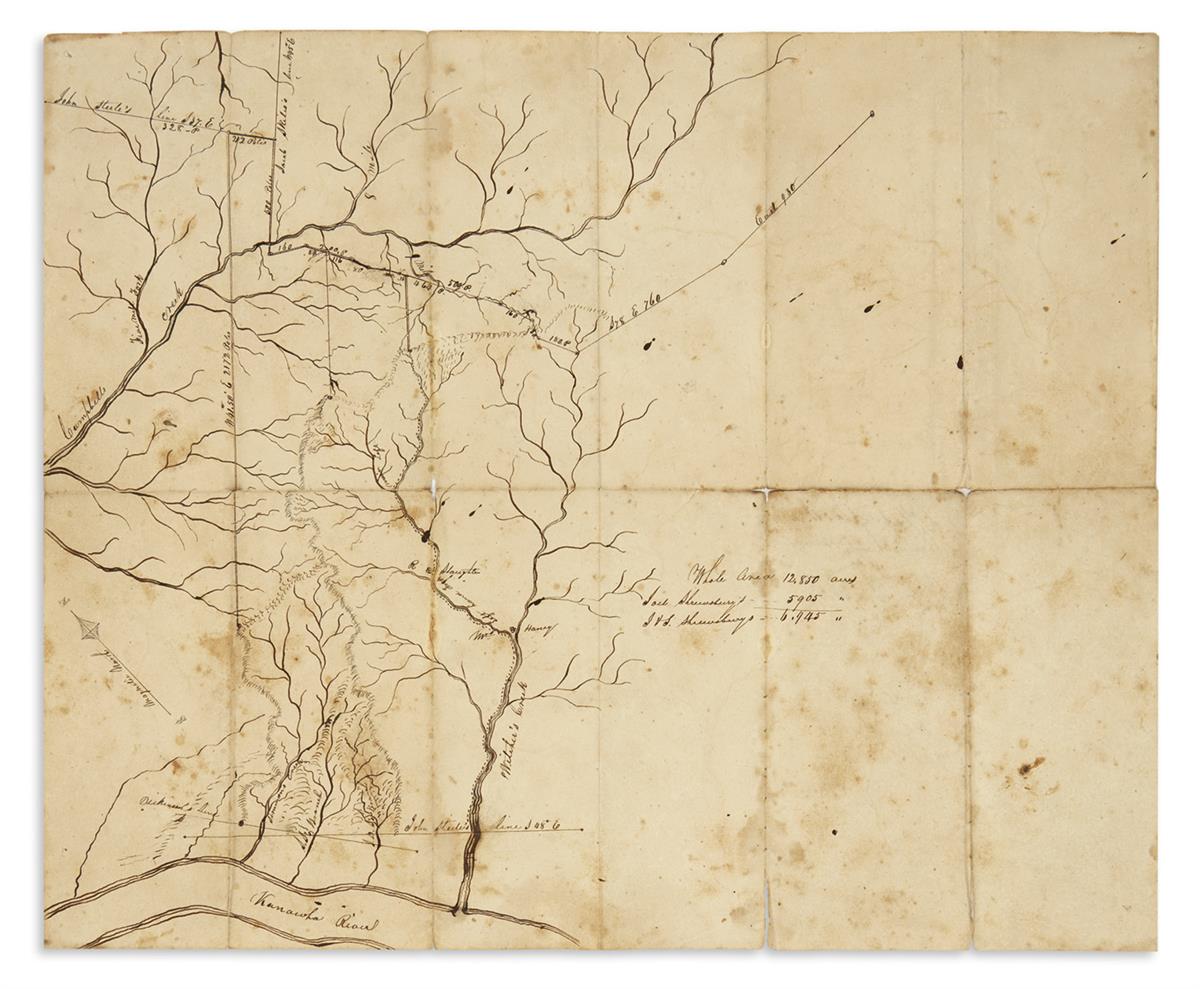

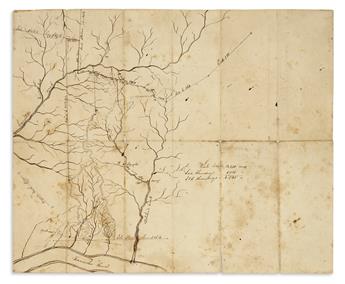

The great bulk of these papers appear to be from the files of William Dickinson Sr. and Jr., or of the Dickinson & Shrewsbury partnership. Three boxes contain mostly correspondence with some receipts and invoices interspersed, and the final box contains 18 folders of records relating to enslaved workers in addition to other miscellaneous records. A 12 1/2 x 15 1/4-inch manuscript map shows land on the Kanawha River purchased by Shrewsbury in 1838. The competing Kanawha salt producers were always prone to overproduction, which they attempted to address through the formation of the Kanawha Salt Association. Found among the files is a small 11-page pamphlet in original wrappers, "Articles and Pledge of the Kanawha Salt Association," printed in Cincinnati in 1848; no other examples have been traced in OCLC. Also included are marketing agreements to distribute salt in various cities through 1863.

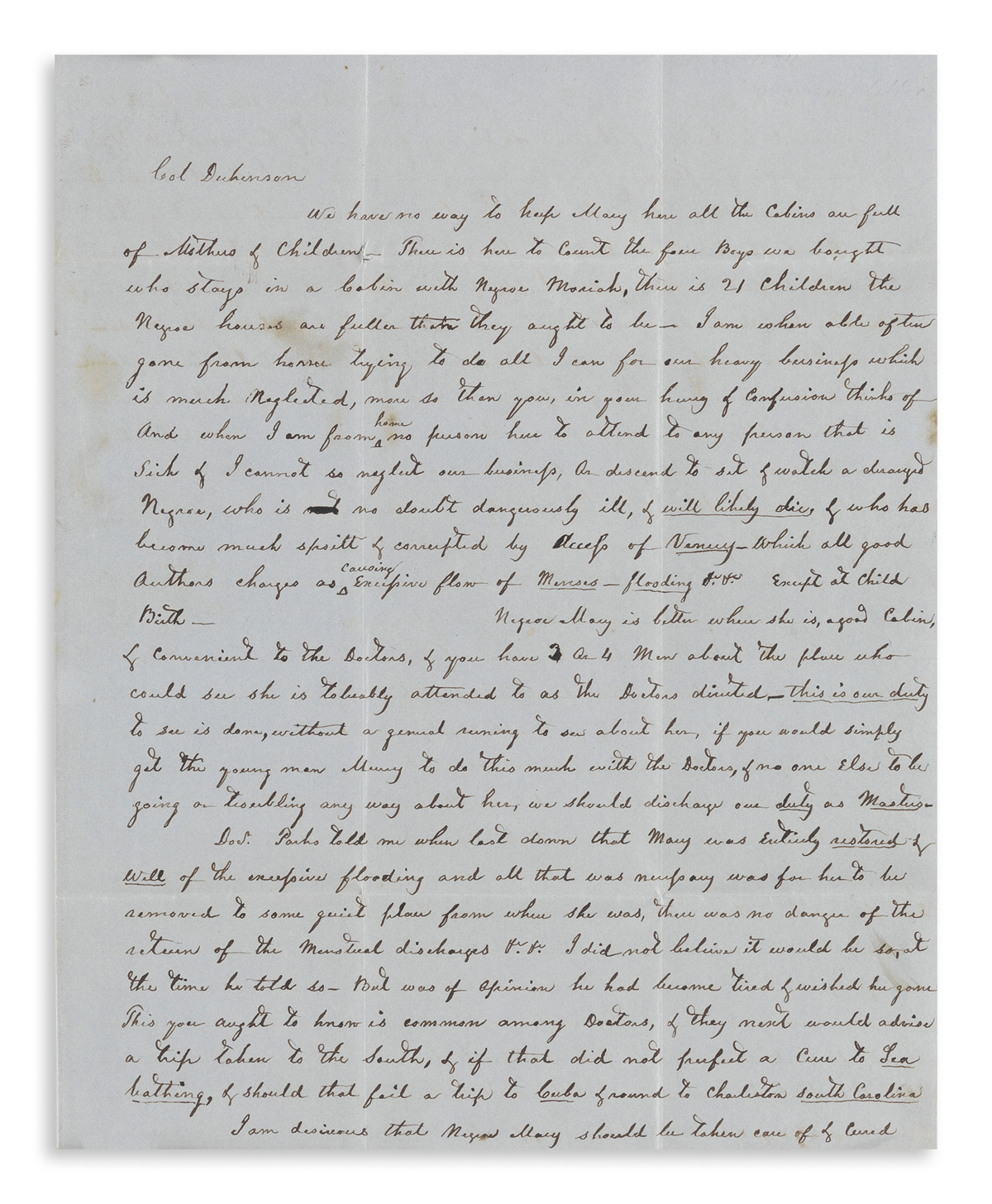

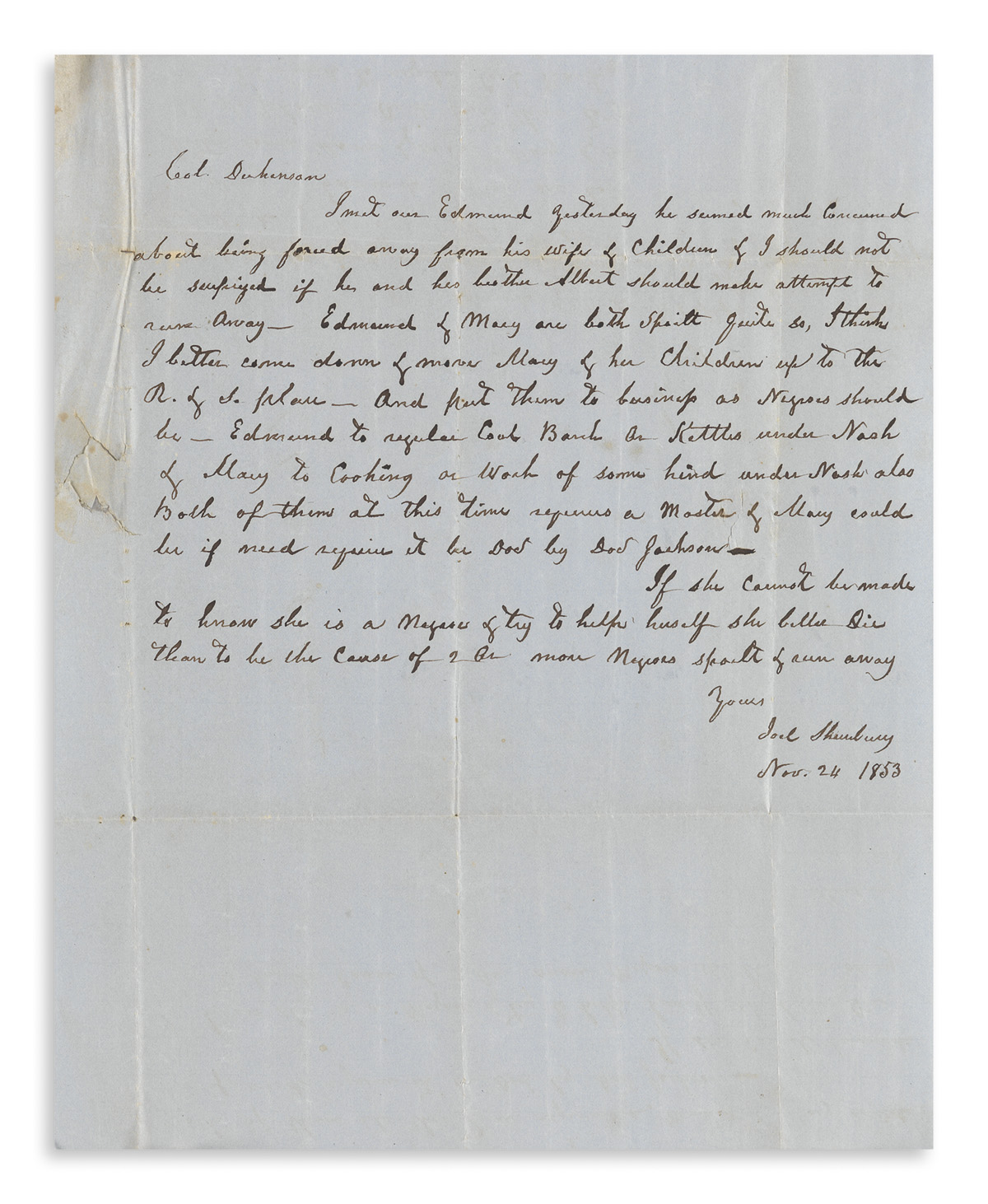

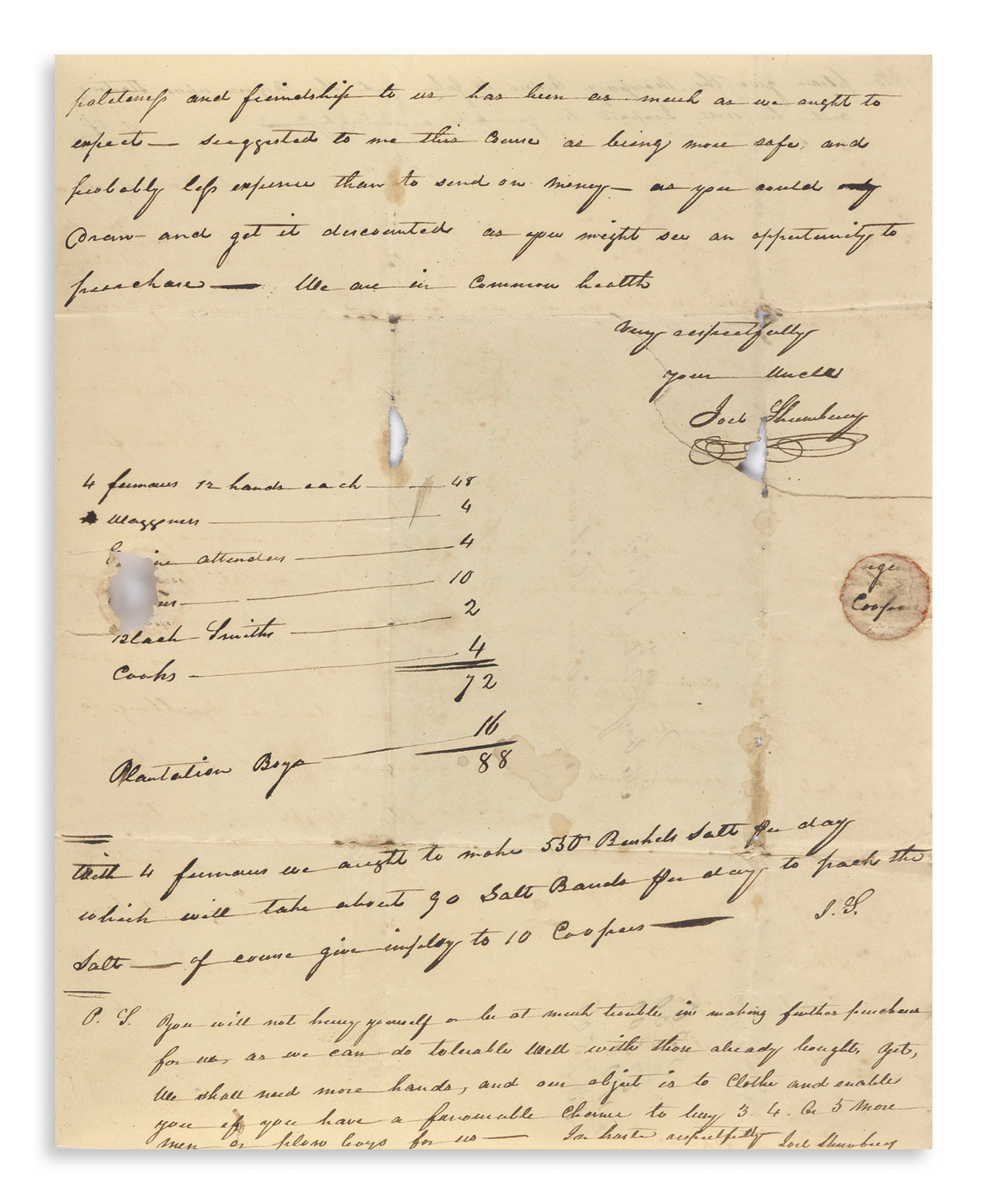

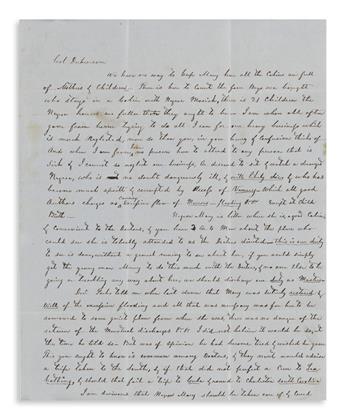

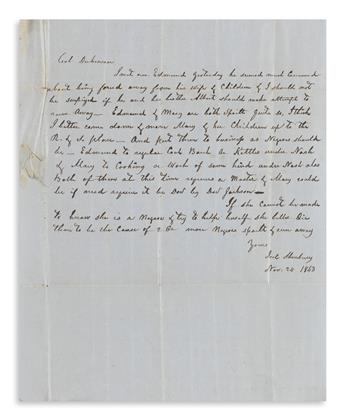

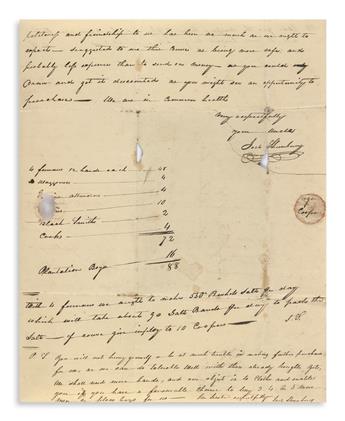

Slave labor is a constant recurring subject in the correspondence. Joel Shrewsbury's letters to his partner were particularly frank and informative. A 22 February 1833 letter summarizes the labor force in a small table: "4 furnaces, 12 hands each--48; Waggoneers--4; Engine attenders--4; [Coopers]--10; Black smiths--2; Cooks--4; Plantation boys--16," for a total enslaved labor force of 88. A couple of decades later, his numbers had grown--a 6 July 1855 letter cites "about 140 to 150 negroes making 400,000 b's of salt per annum." Shrewsbury was particularly troubled by an enslaved woman named Mary in 24 November 1853: "Edmund & Mary are both spoilt quite so, I think. I better come down & move Mary & her children up to the R.&S. place, and put them to business as Negroes should be, Edmund to regular coal bank or kettles under Nash & Mary to cooking. . . . If she cannot be made to know she is a Negroe & try to help herself, she better die than to be the cause of 2 or more Negroes spoilt & run away." Another letter discussing Mary circa 1854 attempts to diagnose her medical ills, blaming them on her sexual activity: "I cannot so neglect our business, or descend to sit & watch a deranged Negroe who is no doubt dangerously ill & will likely die & who has become much spoilt & corrupted by eccess of venery, which all good authors charges as causing excessive flow on menses, flooding &c &c except at child birth." In a 17 September 1854 letter, he plans a hunt for an escapee in great detail, having found a man who "promised to take his son and dogs with him and . . . hunt for the negroes tonight & tomorrow, as long as we may wish him to do. . . . If he can get upon their tracks, he thinks he can make his dogs follow them." On 22 October 1854, Shrewsbury expresses concern over "those white men & free negroes that was at the frolic, or in any way engaged in threats and actions to prevent the patrols from their duty. . . . Our own negroes that was there ought to be whipped for it well at once, to have no time to dodge & plague us, & their Sunday clothes taken from them."

William Dickinson Jr., in a 20 October 1847 letter to his father, muses that the Mexican War and other economic forces might lead to civil war and the doom of slavery: "Why need we contemplate the value of slaves or slave labour years to come, when in truth and in fact take them as a body, big, little, young & old, man, women & children, they do not realize a cent now in this section of Virginia. Those who own them are the greatest slaves & have all the cares & troubles of them."

Among the hundreds of other letters and documents relating to slavery, a few stand out. Slave dealer James L. Ficklen wrote on 29 March 1863 from O'Bannon's Depot in Kentucky, three months after the Emancipation Proclamation had nominally freed the slaves of the south: "I am not buying negroes at this time, but would if it was not for the troubles in our country. I have bought about twenty and sold. The season is now too late to sell." A pair of slave catchers signed a receipt on 29 April 1856 for a $300 reward "in full for takeing up a negro boy named John in the state of Ohio said to belong or to be hired to Mssrs Dickinson & Shrewsbury at Kanawha Salines." Among the travel passes issued to slaves, a typical one dated 12 January 1846 states "let the boys Daniel & James pass from this county to Messrs Dickinson & Shrewsbury at the Kanawha Saline. I have hired them there to work. . . . Let them lie in kitchens at nights. They have the reputation of being good boys where they have worked." Dozens of receipts and letters are marked as hand-delivered by enslaved messengers.

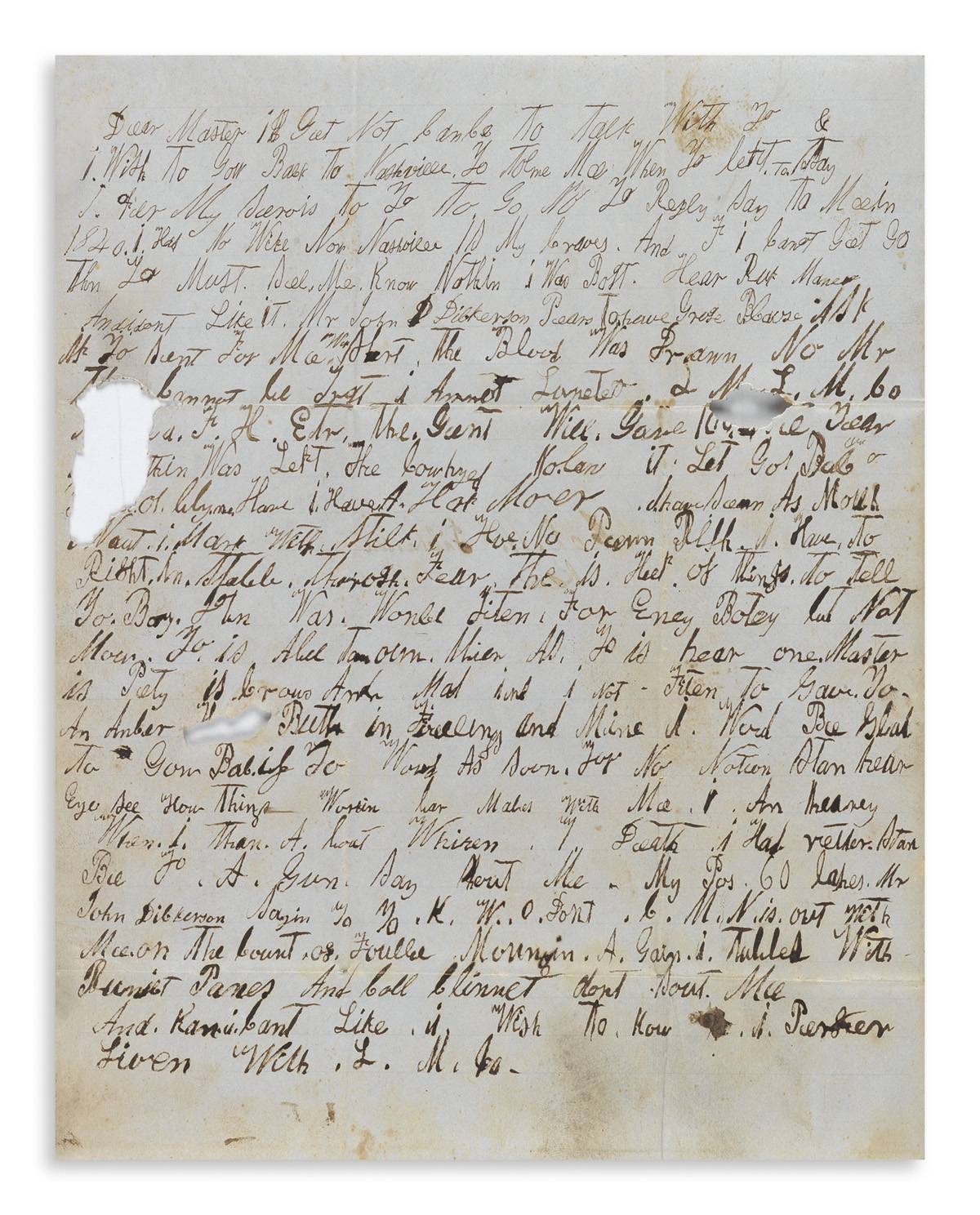

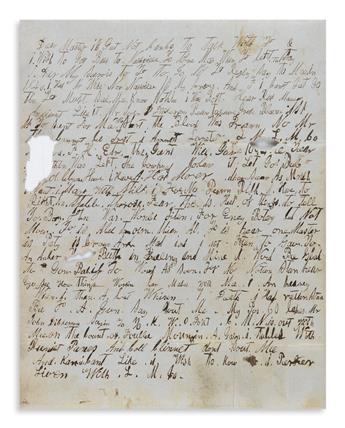

Perhaps most remarkable is a letter sent to William Dickinson by "yo slave boy John Hand" circa 1840. Most letters we have seen by enslaved people were likely written on their behalf. This letter, on the furthest fringe of literacy in a scrawled hand, was clearly written by Hand. He expresses his "wish to gow back to Nashville. Yo tol me when yo left today, to fil my servis to yo . . . yo reply say to mee, in 1840. I has no wife now, Nashville is my graves, and if I can't get to there, yo must sel me. . . . The blood was drawn. . . . Coll climet don't sout me. . . . Now sur, if yo say that yo du not want gow, I will put back in sale. . . . Negro taken and hird him up in a bord, nevier to bring yo back in this state, Tenn, then it was tow late. . . . I won't run away. . . . I wantt to [gow to] Ohio" (slave file #18).

Among the numerous lists and inventories of the slaves owned or hired by Dickinson & Shrewsbury are two small memorandum books. They list names, ages, maladies such as deafness, values, and relationships as of 1858, with additional notes through 1864. Several long lists show groups of "negroes stole off" as the Civil War progressed, the last a group of "Negroes left on this date at night"--19 men, women and children who found freedom on 20 January 1864.

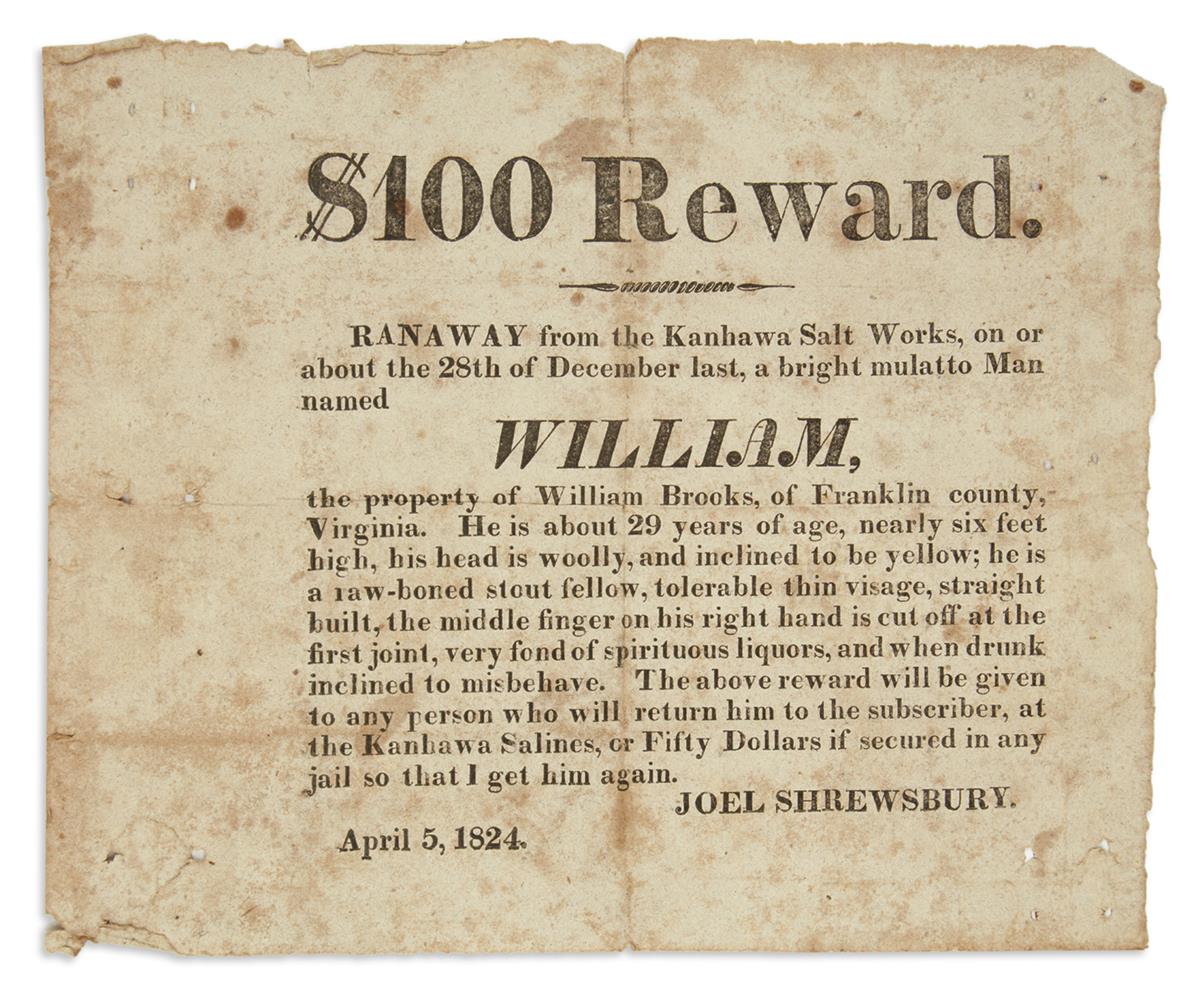

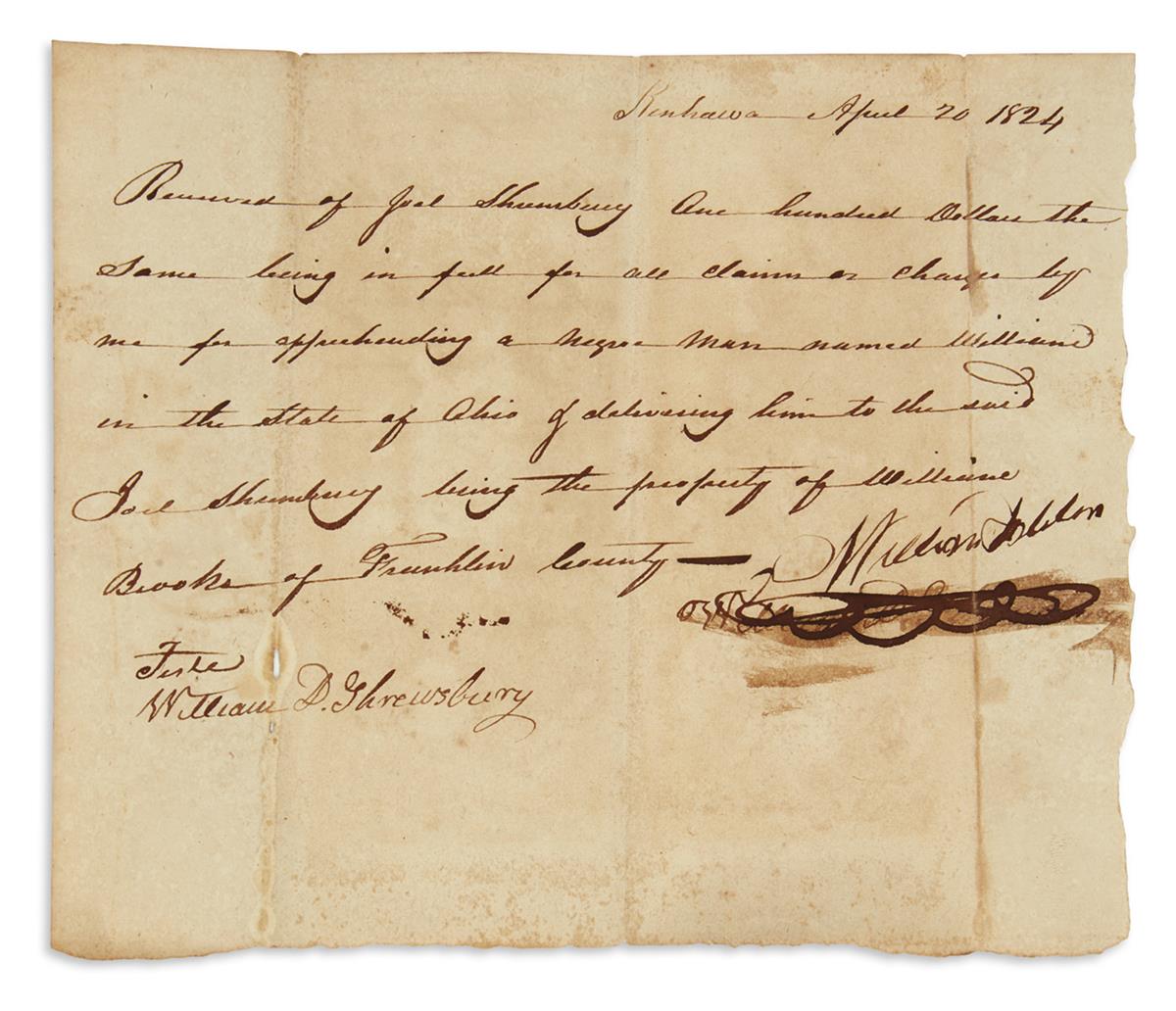

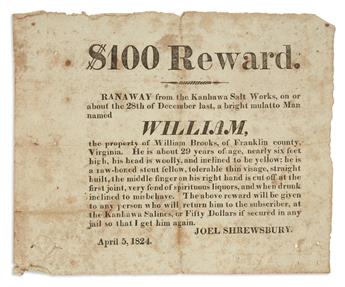

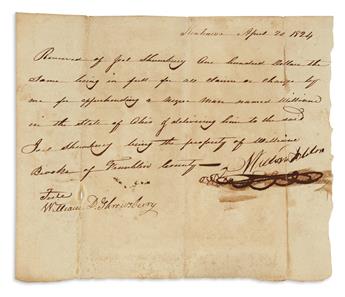

One of the very few printed documents in the collection is a runaway broadside offering a $100 reward: "Ranaway from the Kanawha Salt Works . . . a bright mulatto Man named William, the property of William Brooks of Franklin County, Virginia. He is about 29 years of age, nearly 6 feet high . . . and when drunk inclined to misbehave." It is signed in type by Joel Shrewsbury on 5 April 1824. We trace no other examples in OCLC. In the William Brooks file is the receipt for William's apprehension: one Wilson Dobbins was paid the full $100 by Joel Shrewsbury for apprehending William in Ohio.

The connections between the renowned educator Booker T. Washington and the salt works of Kanawha Salines were numerous and deep. He was born circa 1856 in Hale's Ford, Franklin County, VA, in the eastern foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains, close to Bedford County where Dickinson and Shrewsbury had first joined forces. His mother Jane was enslaved; the name of his white father was not known, but was thought to be likely his owner James Burroughs (1794-1861) or a member of Josiah Ferguson's family on a neighboring plantation. As Dickinson & Shrewsbury's salt works grew, they maintained a pipeline of slave labor from their home region. The collection includes files of correspondence with the Burroughs family, and with T.C. Ferguson who owned Booker's stepfather Washington "Wash" Ferguson. Washington Ferguson had apparently been hired out to work at Kanawha at least intermittently from 1844 onward, returning long enough to marry Booker's mother Jane in the early 1860s. A few months after the war ended, Wash summoned Jane, Booker and the rest of the family to join him in West Virginia. 9-year-old Booker was set to work packing barrels of salt. His stepfather only grudgingly allowed him to attend school between shifts at the salt works, working a schedule of 4 to 9 each morning and then returning for two hours after school. Circa 1867, Booker was able to leave the salt works for life as a household servant with Lewis Ruffner, one of the area's rival salt moguls (and a son-in-law of Joel Shrewsbury). See Harlan, "Booker T. Washington's West Virginia Boyhood," in West Virginia History 32:2 (January 1971), pages 63-85.

A file of Ferguson family correspondence includes a 30 November 1844 letter from T.C. Ferguson which discusses Booker's stepfather Washington Ferguson: "Yours to my brother Josiah has been received, asking to be informed whether he intended letting his negroe boys remain with you the next year. . . . You can have them. . . . His boys are named Charles, Samuel & Washington." Josiah Ferguson wrote on 24 January 1857 that he heard "my negro man Washing. was not hired and that neither Dickinson or Shrewsbury was going to work this year. . . . I wish you to take charge of Washing and do with him as if he was your own."

Thomas Burroughs (1798-1880), brother of Booker T. Washington's owner James, is represented by 4 letters dated 1846-60. The first, dated 5 January 1846 at Hale's Ford, VA (Booker T. Washington's place of birth), discusses his "negro man Creed" being leased to work at the salt works, adding "I expect him to stay for several years." The other three letters attempt to track Creed and collect fees as he is sub-leased to a local coal mine by 1860.

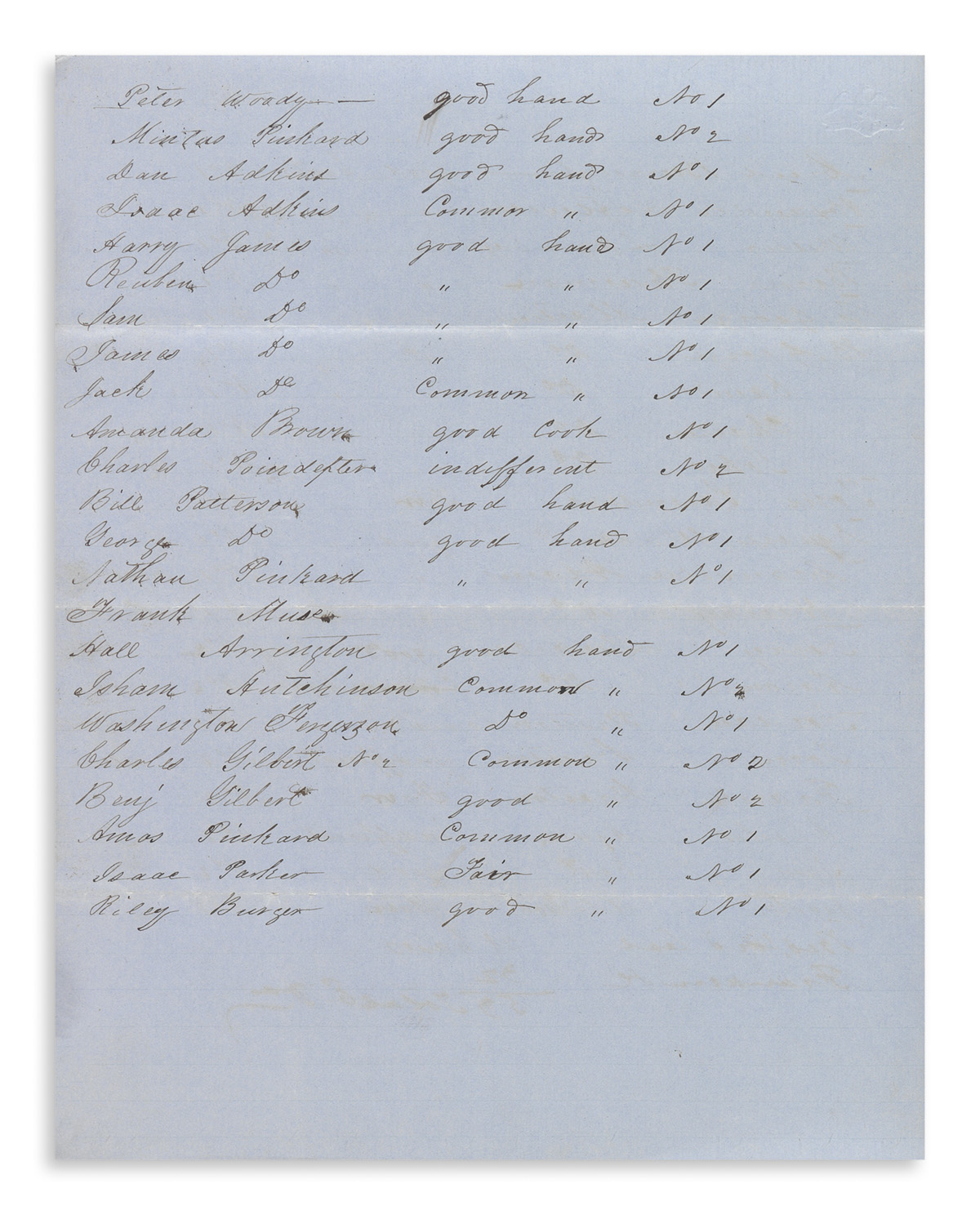

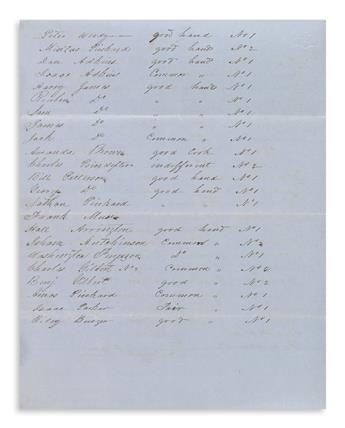

Included are a 4 February 1857 inventory of slaves involved in the Dickinson & Shrewsbury lawsuit, twice naming Washington Ferguson (file 7); and an undated list circa 1855 titled "List of Negroes and Quality" listing 85 slaves employed by Dickinson & Shrewsbury. The list begins with those hired from owners in eastern Virginia counties, including "Creed Burroughs - good hand No. 1" and Washington Ferguson (see Ferguson file). Various slaves with the surnames Burroughs and Ferguson appear continually throughout the collection. Finally, the collection includes 11 letters dated 1846 and 1861-63 from Lewis Ruffner, the rival salt maker who later played such an important role in Booker's development, although we have spotted nothing from the 1867-1872 period where Booker served in the Ruffner household.

Even beyond the content relating to salt production, slavery, and Booker T. Washington, the collection holds considerable interest. A few letters relate to the Civil War. Colonel Samuel A. Gilbert of the 44th Ohio Regiment wrote a friendly letter on 10 June 1862 from camp in Meadow Bluffs, WV: "The Rebels are said to be making loud boasts about coming down here and clearing us out, but we notice that they keep at a long day's march off! We did run like the devil when they got after us as they predicted we would, but the trouble with them was we ran the wrong way!" (Merchant file, box 1). William Dickinson Sr. frequently discussed politics and current events; he wrote to his son William on 29 September 1826 regarding a duel fought by a young Tennessee congressman named Sam Houston, and on 11 March 1827 weighed in on the presidential chances of Andrew Jackson: "I have traveled with him several days & been in his company numbers of times. If he has any claims to greatness (except as to bravery) I am no judge." He wrote an epic 7-page letter describing the Southwestern Convention held in Nashville which featured Henry Clay, 23 August 1840. Two close George Washington relatives settled in Kanawha County. The lot includes an 1820 bond between the president's nephew Laurence Augustine Washington and nephew-in-law Andrew Parks, and other papers relating to the extended Washington family.

Only a small fraction of this important archive on West Virginia industry and slavery has been described here. A more detailed 60-page inventory is available upon request. Sold piece by piece, hundreds of these items would be worthy of individual sale. If kept together, several books and dissertations remain to be written from this evocative material.

The key figures in this archive are William Dickinson (1772-1861) and his brother-in-law Joel Shrewsbury (1779-1859), the founding partners of the firm of Dickinson & Shrewsbury. They began as tobacco merchants in Bedford County, VA. In the winter of 1814-15 they moved west of the Appalachian Mountains to Kanawha County, and acquired land in the Kanawha Salines region north of Charlestown (now the town of Malden). They began their salt-making operation in earnest in 1818, tapping into the remnants of an underwater ocean and using furnaces to boil off the salty water into a marketable product. William Dickinson Jr. (1798-1881) became active in the business by the 1830s. By the 1850s, grandsons Henry C. Dickinson (1830-1871) and John Q. Dickinson (1831-1925) were also playing active roles. The Shrewsbury & Dickinson partnership became acrimonious by 1857, with a messy lawsuit ending in the firm's dissolution in 1861; John Q. Dickinson led the salt works after the war. See Stealy, "Virginia's Mercantile-Manufacturing Frontier: Dickinson & Shrewsbury and the Great Kanawha Salt Industry," in The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 101:4 (October 1993), pages 509-534.

The great bulk of these papers appear to be from the files of William Dickinson Sr. and Jr., or of the Dickinson & Shrewsbury partnership. Three boxes contain mostly correspondence with some receipts and invoices interspersed, and the final box contains 18 folders of records relating to enslaved workers in addition to other miscellaneous records. A 12 1/2 x 15 1/4-inch manuscript map shows land on the Kanawha River purchased by Shrewsbury in 1838. The competing Kanawha salt producers were always prone to overproduction, which they attempted to address through the formation of the Kanawha Salt Association. Found among the files is a small 11-page pamphlet in original wrappers, "Articles and Pledge of the Kanawha Salt Association," printed in Cincinnati in 1848; no other examples have been traced in OCLC. Also included are marketing agreements to distribute salt in various cities through 1863.

Slave labor is a constant recurring subject in the correspondence. Joel Shrewsbury's letters to his partner were particularly frank and informative. A 22 February 1833 letter summarizes the labor force in a small table: "4 furnaces, 12 hands each--48; Waggoneers--4; Engine attenders--4; [Coopers]--10; Black smiths--2; Cooks--4; Plantation boys--16," for a total enslaved labor force of 88. A couple of decades later, his numbers had grown--a 6 July 1855 letter cites "about 140 to 150 negroes making 400,000 b's of salt per annum." Shrewsbury was particularly troubled by an enslaved woman named Mary in 24 November 1853: "Edmund & Mary are both spoilt quite so, I think. I better come down & move Mary & her children up to the R.&S. place, and put them to business as Negroes should be, Edmund to regular coal bank or kettles under Nash & Mary to cooking. . . . If she cannot be made to know she is a Negroe & try to help herself, she better die than to be the cause of 2 or more Negroes spoilt & run away." Another letter discussing Mary circa 1854 attempts to diagnose her medical ills, blaming them on her sexual activity: "I cannot so neglect our business, or descend to sit & watch a deranged Negroe who is no doubt dangerously ill & will likely die & who has become much spoilt & corrupted by eccess of venery, which all good authors charges as causing excessive flow on menses, flooding &c &c except at child birth." In a 17 September 1854 letter, he plans a hunt for an escapee in great detail, having found a man who "promised to take his son and dogs with him and . . . hunt for the negroes tonight & tomorrow, as long as we may wish him to do. . . . If he can get upon their tracks, he thinks he can make his dogs follow them." On 22 October 1854, Shrewsbury expresses concern over "those white men & free negroes that was at the frolic, or in any way engaged in threats and actions to prevent the patrols from their duty. . . . Our own negroes that was there ought to be whipped for it well at once, to have no time to dodge & plague us, & their Sunday clothes taken from them."

William Dickinson Jr., in a 20 October 1847 letter to his father, muses that the Mexican War and other economic forces might lead to civil war and the doom of slavery: "Why need we contemplate the value of slaves or slave labour years to come, when in truth and in fact take them as a body, big, little, young & old, man, women & children, they do not realize a cent now in this section of Virginia. Those who own them are the greatest slaves & have all the cares & troubles of them."

Among the hundreds of other letters and documents relating to slavery, a few stand out. Slave dealer James L. Ficklen wrote on 29 March 1863 from O'Bannon's Depot in Kentucky, three months after the Emancipation Proclamation had nominally freed the slaves of the south: "I am not buying negroes at this time, but would if it was not for the troubles in our country. I have bought about twenty and sold. The season is now too late to sell." A pair of slave catchers signed a receipt on 29 April 1856 for a $300 reward "in full for takeing up a negro boy named John in the state of Ohio said to belong or to be hired to Mssrs Dickinson & Shrewsbury at Kanawha Salines." Among the travel passes issued to slaves, a typical one dated 12 January 1846 states "let the boys Daniel & James pass from this county to Messrs Dickinson & Shrewsbury at the Kanawha Saline. I have hired them there to work. . . . Let them lie in kitchens at nights. They have the reputation of being good boys where they have worked." Dozens of receipts and letters are marked as hand-delivered by enslaved messengers.

Perhaps most remarkable is a letter sent to William Dickinson by "yo slave boy John Hand" circa 1840. Most letters we have seen by enslaved people were likely written on their behalf. This letter, on the furthest fringe of literacy in a scrawled hand, was clearly written by Hand. He expresses his "wish to gow back to Nashville. Yo tol me when yo left today, to fil my servis to yo . . . yo reply say to mee, in 1840. I has no wife now, Nashville is my graves, and if I can't get to there, yo must sel me. . . . The blood was drawn. . . . Coll climet don't sout me. . . . Now sur, if yo say that yo du not want gow, I will put back in sale. . . . Negro taken and hird him up in a bord, nevier to bring yo back in this state, Tenn, then it was tow late. . . . I won't run away. . . . I wantt to [gow to] Ohio" (slave file #18).

Among the numerous lists and inventories of the slaves owned or hired by Dickinson & Shrewsbury are two small memorandum books. They list names, ages, maladies such as deafness, values, and relationships as of 1858, with additional notes through 1864. Several long lists show groups of "negroes stole off" as the Civil War progressed, the last a group of "Negroes left on this date at night"--19 men, women and children who found freedom on 20 January 1864.

One of the very few printed documents in the collection is a runaway broadside offering a $100 reward: "Ranaway from the Kanawha Salt Works . . . a bright mulatto Man named William, the property of William Brooks of Franklin County, Virginia. He is about 29 years of age, nearly 6 feet high . . . and when drunk inclined to misbehave." It is signed in type by Joel Shrewsbury on 5 April 1824. We trace no other examples in OCLC. In the William Brooks file is the receipt for William's apprehension: one Wilson Dobbins was paid the full $100 by Joel Shrewsbury for apprehending William in Ohio.

The connections between the renowned educator Booker T. Washington and the salt works of Kanawha Salines were numerous and deep. He was born circa 1856 in Hale's Ford, Franklin County, VA, in the eastern foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains, close to Bedford County where Dickinson and Shrewsbury had first joined forces. His mother Jane was enslaved; the name of his white father was not known, but was thought to be likely his owner James Burroughs (1794-1861) or a member of Josiah Ferguson's family on a neighboring plantation. As Dickinson & Shrewsbury's salt works grew, they maintained a pipeline of slave labor from their home region. The collection includes files of correspondence with the Burroughs family, and with T.C. Ferguson who owned Booker's stepfather Washington "Wash" Ferguson. Washington Ferguson had apparently been hired out to work at Kanawha at least intermittently from 1844 onward, returning long enough to marry Booker's mother Jane in the early 1860s. A few months after the war ended, Wash summoned Jane, Booker and the rest of the family to join him in West Virginia. 9-year-old Booker was set to work packing barrels of salt. His stepfather only grudgingly allowed him to attend school between shifts at the salt works, working a schedule of 4 to 9 each morning and then returning for two hours after school. Circa 1867, Booker was able to leave the salt works for life as a household servant with Lewis Ruffner, one of the area's rival salt moguls (and a son-in-law of Joel Shrewsbury). See Harlan, "Booker T. Washington's West Virginia Boyhood," in West Virginia History 32:2 (January 1971), pages 63-85.

A file of Ferguson family correspondence includes a 30 November 1844 letter from T.C. Ferguson which discusses Booker's stepfather Washington Ferguson: "Yours to my brother Josiah has been received, asking to be informed whether he intended letting his negroe boys remain with you the next year. . . . You can have them. . . . His boys are named Charles, Samuel & Washington." Josiah Ferguson wrote on 24 January 1857 that he heard "my negro man Washing. was not hired and that neither Dickinson or Shrewsbury was going to work this year. . . . I wish you to take charge of Washing and do with him as if he was your own."

Thomas Burroughs (1798-1880), brother of Booker T. Washington's owner James, is represented by 4 letters dated 1846-60. The first, dated 5 January 1846 at Hale's Ford, VA (Booker T. Washington's place of birth), discusses his "negro man Creed" being leased to work at the salt works, adding "I expect him to stay for several years." The other three letters attempt to track Creed and collect fees as he is sub-leased to a local coal mine by 1860.

Included are a 4 February 1857 inventory of slaves involved in the Dickinson & Shrewsbury lawsuit, twice naming Washington Ferguson (file 7); and an undated list circa 1855 titled "List of Negroes and Quality" listing 85 slaves employed by Dickinson & Shrewsbury. The list begins with those hired from owners in eastern Virginia counties, including "Creed Burroughs - good hand No. 1" and Washington Ferguson (see Ferguson file). Various slaves with the surnames Burroughs and Ferguson appear continually throughout the collection. Finally, the collection includes 11 letters dated 1846 and 1861-63 from Lewis Ruffner, the rival salt maker who later played such an important role in Booker's development, although we have spotted nothing from the 1867-1872 period where Booker served in the Ruffner household.

Even beyond the content relating to salt production, slavery, and Booker T. Washington, the collection holds considerable interest. A few letters relate to the Civil War. Colonel Samuel A. Gilbert of the 44th Ohio Regiment wrote a friendly letter on 10 June 1862 from camp in Meadow Bluffs, WV: "The Rebels are said to be making loud boasts about coming down here and clearing us out, but we notice that they keep at a long day's march off! We did run like the devil when they got after us as they predicted we would, but the trouble with them was we ran the wrong way!" (Merchant file, box 1). William Dickinson Sr. frequently discussed politics and current events; he wrote to his son William on 29 September 1826 regarding a duel fought by a young Tennessee congressman named Sam Houston, and on 11 March 1827 weighed in on the presidential chances of Andrew Jackson: "I have traveled with him several days & been in his company numbers of times. If he has any claims to greatness (except as to bravery) I am no judge." He wrote an epic 7-page letter describing the Southwestern Convention held in Nashville which featured Henry Clay, 23 August 1840. Two close George Washington relatives settled in Kanawha County. The lot includes an 1820 bond between the president's nephew Laurence Augustine Washington and nephew-in-law Andrew Parks, and other papers relating to the extended Washington family.

Only a small fraction of this important archive on West Virginia industry and slavery has been described here. A more detailed 60-page inventory is available upon request. Sold piece by piece, hundreds of these items would be worthy of individual sale. If kept together, several books and dissertations remain to be written from this evocative material.

Exhibition Hours

Exhibition Hours

Aliquam vulputate ornare congue. Vestibulum maximus, libero in placerat faucibus, risus nisl molestie massa, ut maximus metus lectus vel lorem.