Sale 2308 - Lot 44

Price Realized: $ 55,000

Price Realized: $ 66,000

?Final Price Realized includes Buyer’s Premium added to Hammer Price

Estimate: $ 30,000 - $ 40,000

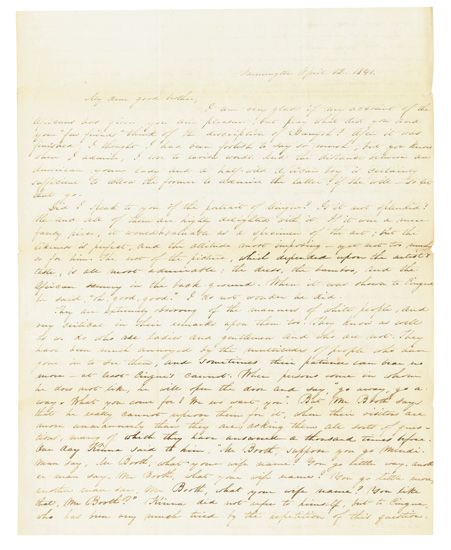

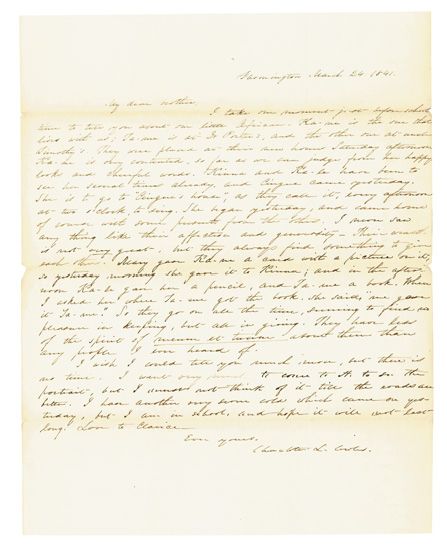

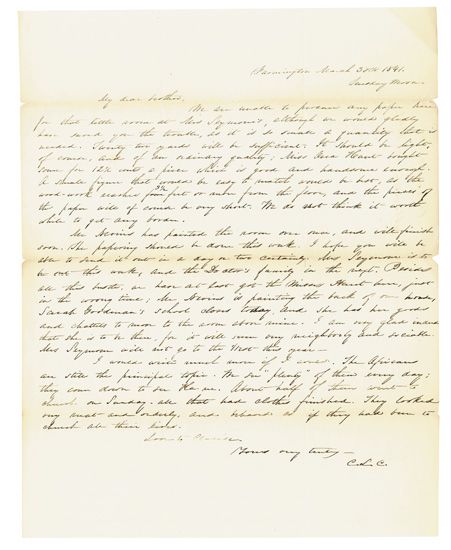

EXTRAORDINARY (SLAVERY AND ABOLITION--AMISTAD CAPTIVES.) Group of ninety-one letters written by Charlotte Cowles to her bother Samuel, with three letters from Samuel to Charlotte. Almost entirely 4to's average 1-1/2 as many as 3 or 4 pages; condition generally very good with only two or three with any significant damage. Farmington, and Hartford, CT, 1833-1846

Additional Details

an exceptionally rich, contemporary chronicle of an abolitionist family and their dealings with cinque, grabeau, kin-nah and others of the amistad captives.On February 22, 1841, following the drawn out trial of the Amistad captives, Judge Joseph Story read his opinion, declaring the Mende Africans to be free. Free indeed, but not able to afford the passage home to Sierra Leone. As a result, many of the Connecticut abolitionists who had supported them during their trials took them into their homes while funds were being raised.

Horace Cowles, Samuel Deming, Elijah Lewis and Stephen Austin were active conductors on the Farmington Connecticut Underground Railroad, and members of the Amistad Committee. All helped house and feed the Mende while they waited to go home--- and all figure prominently in these letters from Charlotte Cowles (1820-1866) to her brother Samuel (1814-1872). One of the Mende children, a little girl named Te-meh, "frog," (spelled Tenyeh by Charlotte) lived with the Cowles family. While in Farmington, the Amistad Committee required that the Mende attend the First Congregational Church, as well as receive five hours of schooling each morning at Samuel Deming's store. They were also taken to different parts of New England and asked to participate in various fundraising events. Their reaction to this and the repeated questions asked of them is also recounted in these letters. With the money raised at these events, the Committee hoped to pay their passage home and establish a Christian mission in Africa.

Charlotte's letters to her brother begin in 1833, and are at first just the sort of talk of home that one might expect. Though, as time passes, Samuel becomes editor of The Charter Oak, an abolitionist newspaper, and Charlotte becomes a founding member of the Farmington Ladies Anti-Slavery Society. So it is from a decidedly Abolitionist point of view that the bulk of these letters hereafter are written. Beginning in 1838 and 1839, Charlotte's letters contain more and more about slavery and the intransigence of some of the local gentry. Two of the three letters from Samuel discuss acts of vandalism to the Charter Oak office and the book depository in Hartford. Charlotte writes about "Thomas," who stayed with the Cowles while on his flight to Canada, "the land of freedom." There are many letters with good content between 1839 and 1840, but in 1841, with the arrival of the Mende, Charlotte's letters become truly rich in content. On March 24th, 1841 we have the first mention of the Africans with the visit of Cinque and others to see Tenyeh (Te-meh), "the one who lives with us." On the 30th there is another mention of the Africans, and how they'd behaved "as if they had been to church all their lives." April 8, 1841, Charlotte writes how the Mende, had been jubilant at being freed from the Hartford jail and taken into the homes of their protectors---how they'd sung "a wild song"---no doubt so, especially to Western ears. She goes on and discuss Cinque, saying "I do wish you could be here to enjoy as we have these poor beings. Tenyeh, (Te-meh) as we have at last learned to spell her name is very happy with us and we have become acquainted with the greater part of them from their coming here to see (her)." She tells of Cinque's reaction to being shown his portrait, "Oh good, good," he says, and Charlotte says something quite telling about white people's perception of blacks as individuals: ". . .we are all satisfied of one thing at least, that there is a great variety of personal appearance. . . it is hard to imagine that these are the same beings I saw in the Hartford jail---except indeed Grabeau---so changed is their whole appearance in complexion, manner and comportance, (sic ); they looked a little dusky yellow, like some of our mulattos, and very disagreeable, but now they are so black and some of them so handsome (underlining hers). . . There was one, very slender one, a laughing genius, and very bright, whom you pointed out to me, but I cannot remember his name. Pray tell me so that I can look him out." This, it turns out from other letters, is Kin-nah, whom she describes as "now at the head of affairs, next to Cinque, and in many things Cinque takes his advice. It is really wonderful to hear him read and see how he understands everything. In a letter dated April 12, 1841, Charlotte tells how "One evening, Henyeh told us a great deal about her adventures, all the way from Mendi to Farmington. She said that at Lomboko she was burnt upon her shoulder with a red-hot pipe. I asked her to let me see the spot, not at all doubting her word. She looked up at me and said 'you think me tell lie? You look there." She writes "I am very glad if my narrative of the Africans has given you any pleasure." Indeed, Charlotte's letters, in a real sense convey a first-hand, collective slave narrative of the Amistad captives, through their voices. Charlotte quotes in full, a touching note written by a man named Foni to his teacher Mr. Booth. In another letter, she realizes that perhaps she has been a little too effusive about a particular young man: "What did you and your friends think of the description of Baqua? After it was finished I thought I had been foolish to say so much, but you know when I admire, I love to lavish words. And the distance between an American young lady and a half wild African boy is certainly sufficient to allow the former to admire the latter, if she will---so let that go." Charlotte's letters provide us with a rare look at an extraordinary sequence of events in American history, seen through the eyes of a twenty-one year old young lady.

Horace Cowles, Samuel Deming, Elijah Lewis and Stephen Austin were active conductors on the Farmington Connecticut Underground Railroad, and members of the Amistad Committee. All helped house and feed the Mende while they waited to go home--- and all figure prominently in these letters from Charlotte Cowles (1820-1866) to her brother Samuel (1814-1872). One of the Mende children, a little girl named Te-meh, "frog," (spelled Tenyeh by Charlotte) lived with the Cowles family. While in Farmington, the Amistad Committee required that the Mende attend the First Congregational Church, as well as receive five hours of schooling each morning at Samuel Deming's store. They were also taken to different parts of New England and asked to participate in various fundraising events. Their reaction to this and the repeated questions asked of them is also recounted in these letters. With the money raised at these events, the Committee hoped to pay their passage home and establish a Christian mission in Africa.

Charlotte's letters to her brother begin in 1833, and are at first just the sort of talk of home that one might expect. Though, as time passes, Samuel becomes editor of The Charter Oak, an abolitionist newspaper, and Charlotte becomes a founding member of the Farmington Ladies Anti-Slavery Society. So it is from a decidedly Abolitionist point of view that the bulk of these letters hereafter are written. Beginning in 1838 and 1839, Charlotte's letters contain more and more about slavery and the intransigence of some of the local gentry. Two of the three letters from Samuel discuss acts of vandalism to the Charter Oak office and the book depository in Hartford. Charlotte writes about "Thomas," who stayed with the Cowles while on his flight to Canada, "the land of freedom." There are many letters with good content between 1839 and 1840, but in 1841, with the arrival of the Mende, Charlotte's letters become truly rich in content. On March 24th, 1841 we have the first mention of the Africans with the visit of Cinque and others to see Tenyeh (Te-meh), "the one who lives with us." On the 30th there is another mention of the Africans, and how they'd behaved "as if they had been to church all their lives." April 8, 1841, Charlotte writes how the Mende, had been jubilant at being freed from the Hartford jail and taken into the homes of their protectors---how they'd sung "a wild song"---no doubt so, especially to Western ears. She goes on and discuss Cinque, saying "I do wish you could be here to enjoy as we have these poor beings. Tenyeh, (Te-meh) as we have at last learned to spell her name is very happy with us and we have become acquainted with the greater part of them from their coming here to see (her)." She tells of Cinque's reaction to being shown his portrait, "Oh good, good," he says, and Charlotte says something quite telling about white people's perception of blacks as individuals: ". . .we are all satisfied of one thing at least, that there is a great variety of personal appearance. . . it is hard to imagine that these are the same beings I saw in the Hartford jail---except indeed Grabeau---so changed is their whole appearance in complexion, manner and comportance, (sic ); they looked a little dusky yellow, like some of our mulattos, and very disagreeable, but now they are so black and some of them so handsome (underlining hers). . . There was one, very slender one, a laughing genius, and very bright, whom you pointed out to me, but I cannot remember his name. Pray tell me so that I can look him out." This, it turns out from other letters, is Kin-nah, whom she describes as "now at the head of affairs, next to Cinque, and in many things Cinque takes his advice. It is really wonderful to hear him read and see how he understands everything. In a letter dated April 12, 1841, Charlotte tells how "One evening, Henyeh told us a great deal about her adventures, all the way from Mendi to Farmington. She said that at Lomboko she was burnt upon her shoulder with a red-hot pipe. I asked her to let me see the spot, not at all doubting her word. She looked up at me and said 'you think me tell lie? You look there." She writes "I am very glad if my narrative of the Africans has given you any pleasure." Indeed, Charlotte's letters, in a real sense convey a first-hand, collective slave narrative of the Amistad captives, through their voices. Charlotte quotes in full, a touching note written by a man named Foni to his teacher Mr. Booth. In another letter, she realizes that perhaps she has been a little too effusive about a particular young man: "What did you and your friends think of the description of Baqua? After it was finished I thought I had been foolish to say so much, but you know when I admire, I love to lavish words. And the distance between an American young lady and a half wild African boy is certainly sufficient to allow the former to admire the latter, if she will---so let that go." Charlotte's letters provide us with a rare look at an extraordinary sequence of events in American history, seen through the eyes of a twenty-one year old young lady.

Exhibition Hours

Exhibition Hours

Aliquam vulputate ornare congue. Vestibulum maximus, libero in placerat faucibus, risus nisl molestie massa, ut maximus metus lectus vel lorem.