Sale 2687 - Lot 217

Unsold

Estimate: $ 15,000 - $ 25,000

(SPORTS--BASEBALL.) Correspondence of an early baseball club secretary from Oneida, New York. Approximately 95 items in one binder, including 64 letters addressed to Homer E. Chapin of Oneida, NY; condition generally strong, many letters with original envelopes (often with stamps removed). Various places, bulk 1863-1870

Additional Details

Baseball had its roots in the eighteenth century or earlier, but it did not start to take root as an organized national pastime until the late 1850s. By 1860, many towns across the country had their own amateur nine. The town nines largely disappeared during the Civil War, but games were frequently played on the front, and returning soldiers took the game to a new level of popularity in 1866.

These letters were addressed to Homer E. Chapin (1847-1943) of Oneida, NY. 36 of them, from 1866 to 1870, are addressed to Chapin in his official capacity as secretary of the Atlantic Junior Base Ball Club of Oneida (they dropped the "Junior" in 1867), and several other social letters from friends also discuss baseball.

In this early amateur era of baseball, clubs did not play centrally arranged schedules--the team secretaries would arrange dates individually with their opponents. For out of town opponents, this would be handled by mail, sometimes over the preceding winter, sometimes just days in advance. For example, one of the earliest baseball letters here is dated 6 July 1866 from the Syracuse Arctics, located 30 miles to the west: "At a regular meeting of the Artics last evening, it was resolved to send your club a challenge. Game to be played on Thursday next week on your grounds. Our club will leave on the one-twenty train if the challenge is accepted." Similar correspondence is present from the Armory Base Ball Club of Ilion, Star Base Ball Club of Chittenango, Eckford Base Ball Club of Syracuse, Clipper Base Ball Club of Syracuse, Independent Base Ball Club of New York Mills, Amateur Base Ball Club of Auburn, and clubs in Rome, Canastota, Verona, Cazenovia, and Knoxboro, NY. The secretary of the Clifton Springs club boasted of their recent string of resounding victories on 16 June 1869, and in closing joked: "If you want to win, bring your umpire with you."

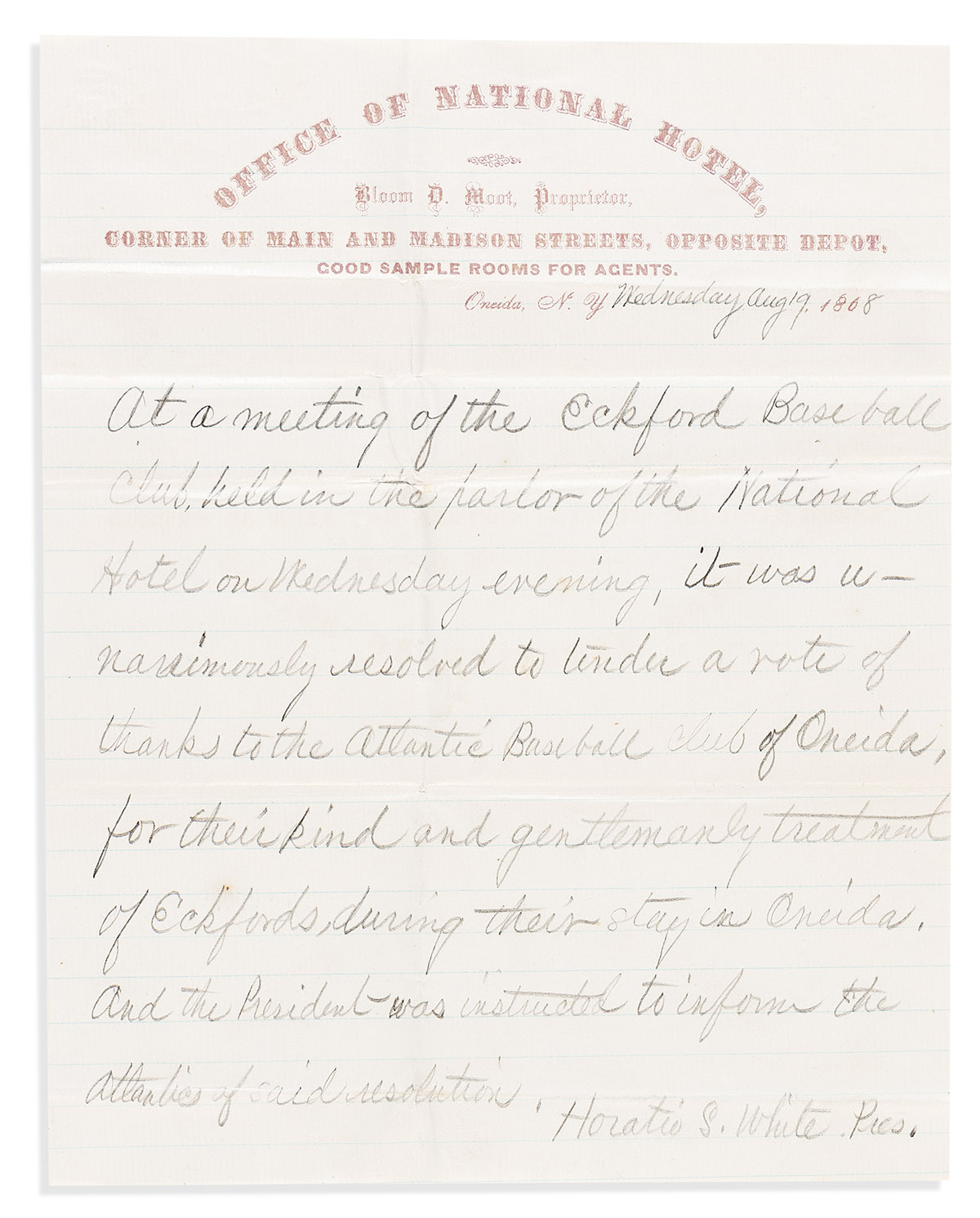

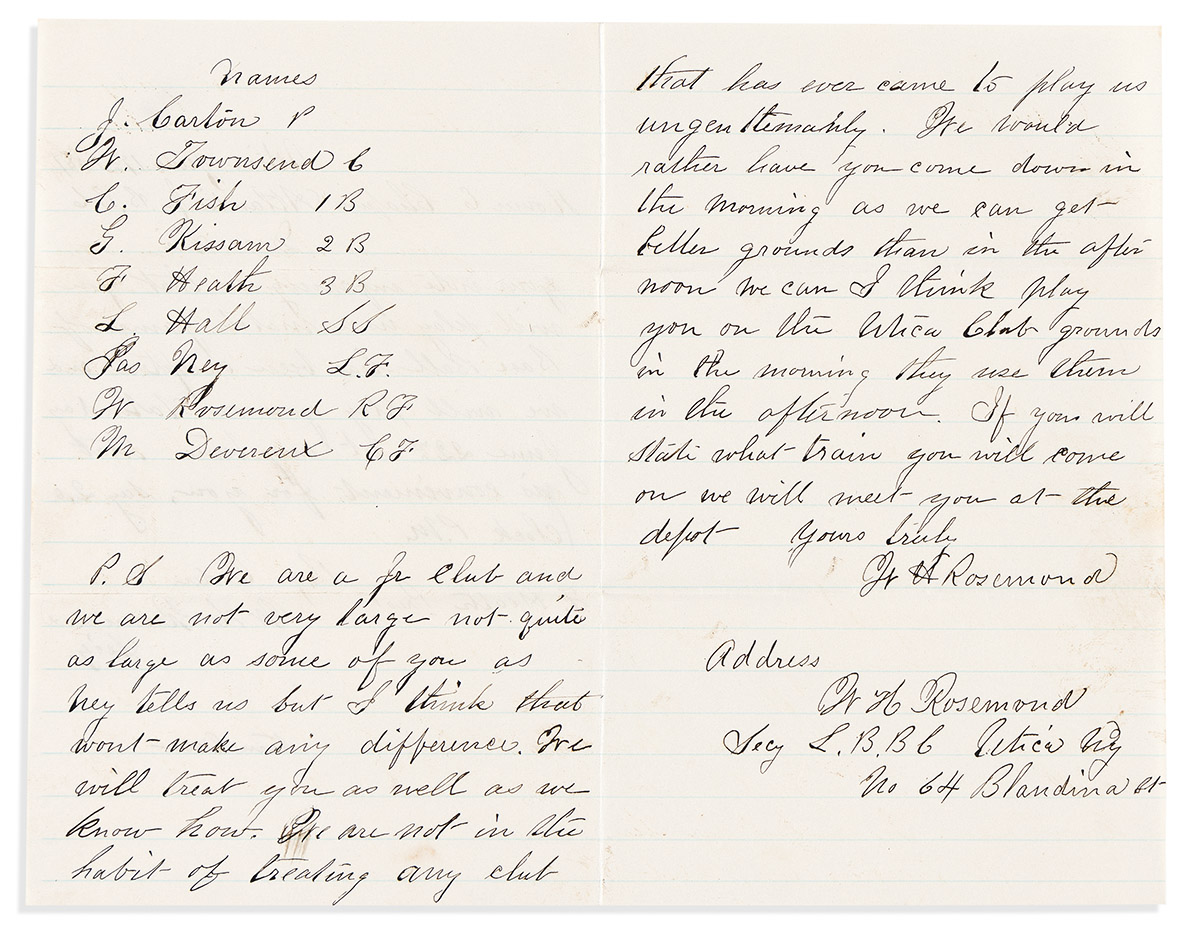

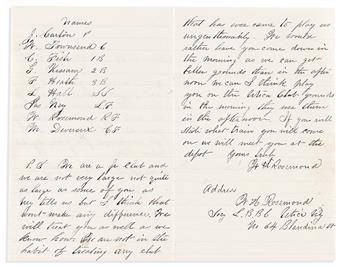

One 17 June 1867 challenge letter from the Utica Juniors went a bit further than most, listing their starting lineup and managing expectations: "We are a jr. club and we are not very large, not quite as large as some of you, as Ney tells us, but . . . we will treat you as well as we know how." They did not have their own grounds, or any means of reserving grounds: "We would rather have you come down in the morning as we can get better grounds than in the afternoon." Host clubs often provided banquets or other refreshments to visiting clubs. In August 1868, the Eckford club sent a formal "vote of thanks . . . for their kind and gentlemanly treatment of Eckfords during their stay in Oneida."

The highest of stakes was presented to the Atlantic Juniors by their crosstown rivals, the Oneida Base Ball Club, on 1 October 1866, which wanted to merge the two clubs: "If you are the victors, the two clubs will immediately consolidate under the name of the Atlantic Club of Oneida; and if we are the victors, the consolidation to be named the Oneida Club of Oneida." We don't know if that epic match was ever played, but the clubs remained separate the next year. The Atlantic club did not drop "Junior" from their name until the following June, and the Oneida club was still going the following August.

The exact definition of amateur was in flux by the late 1860s. A team in Bridgeport, NY accepted a challenge on 13 August 1869, but "there is some of our club is opposed to playing for money, and therefore we cannot accept your challenge to play for $50. . . . If you should want to bet money, there will be plenty of chances. We will also meet you at Manlius at any time you may choose and play for a ball."

In the first flowering of baseball as a mass entertainment, baseball supplies became a profitable industry. Chapin received a letter on 16 May 1867 from Edward H. Williams, a supplier in nearby Utica who described himself as an agent for "one of the largest base ball depots in New York." He enclosed his business card as a "manufacturer and dealer in hats and caps" as well as "fancy furs." Partner J.D. Williams wrote on 21 June 1867: "We did not receive your order untill last ev'g and it will be impossible for me to get them done by the time you want them. . . . I have got them all cut out and ready to make as soon as the girl gets time." A friend wrote from Clifton Springs on 16 July 1867: "I wish you would see Mr. Douglas and find out what he will charge for 6 Star balls."

The Atlantics undoubtedly took the inspiration for their name from the Atlantic Base Ball Club of Brooklyn, which went undefeated against the highest level of competition in 1865 and claimed the championship in 1866. However, this Atlantic nine was based in north-central New York state, many hours from New York City by train. Many of their local competition also took their inspiration from the high-class downstate teams, such as the Eckfords of Brooklyn. However, we find only one letter discussing the big city. Homer's younger brother Taylor Chapin (1849-1942) wrote on 1 June (year unknown) to describe his visit: "We went up to the Battery where the emigrants land, then to Central Park . . . up to Harlem Lane to see the fast horses . . . to the Olympic Theatre to see Humpty Dumpty." However, he did not take in a ballgame; on returning to Oneida, he noted that "base ball is quiet."

A friend named George R. Smith moved to Plymouth, Michigan and wrote on 8 April 1868 to boast that he had beaten the town's best billiard player on his first night out. He added: "The next thing was base ball. They asked me up to play with them the next day. . . . They have got a good club here. They have got as good a catcher as Sanford is. He used to catch in the best club in Detroit and he will get a ball if there is any gets pass the bat. . . . The left fielder is a mighty smart fellow. He has been with a circus for ten years." Smith wrote two weeks later to boast that his Red Rovers Base Ball Club was playing their Michigan neighbors from Northville for a $40 purse: "We will take the conceit out of them."

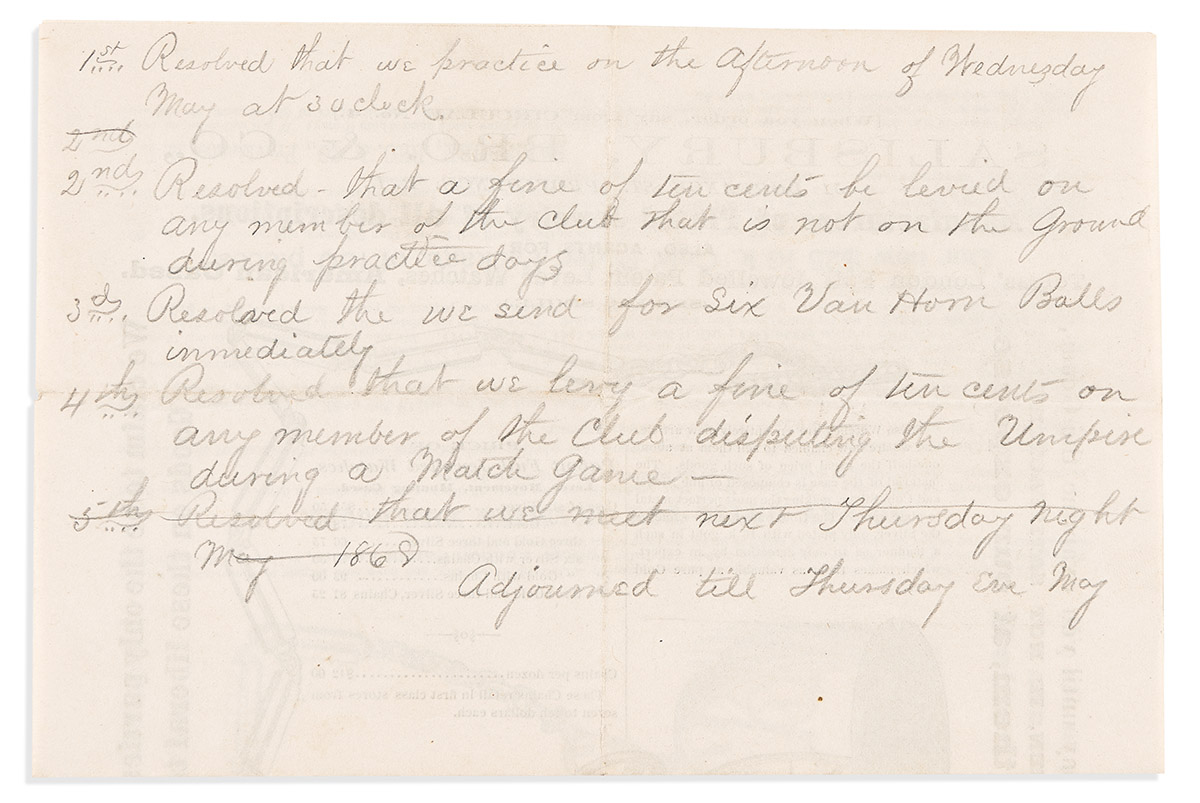

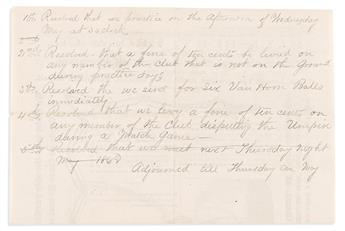

In addition to the correspondence, Secretary Chapin also wrote out a draft of the minutes to a May 1868 club meeting on the back of a jewelry circular, resolving to impose a ten-cent fine on "any member of the club that is not on the ground during practice days" or "any member of the club disputing the umpire during a match game."

The correspondence largely ends in 1870, but an outlying 1875 letter suggests that Chapin was still involved in baseball as he approached his thirties: "Will you please give me what information you can about Sullivan, who caught for the K.K.K.'s last season, in regard to his habits, playing abilities, and P.O. address."

In addition to the baseball content, this lot also contains additional correspondence from Chapin's friends going back to 1863, including several letters from William H. Overacre while enrolled at Western Union College and Military Academy in Illinois, who then enlisted in a Wisconsin artillery regiment and sent letters from training camp. Overacre died in the service in 1864, and his mother wrote to inform Chapin.

This archive offers an unusually detailed look at how the national game was organized and experienced in its very early years, before the first openly professional clubs were formed.

These letters were addressed to Homer E. Chapin (1847-1943) of Oneida, NY. 36 of them, from 1866 to 1870, are addressed to Chapin in his official capacity as secretary of the Atlantic Junior Base Ball Club of Oneida (they dropped the "Junior" in 1867), and several other social letters from friends also discuss baseball.

In this early amateur era of baseball, clubs did not play centrally arranged schedules--the team secretaries would arrange dates individually with their opponents. For out of town opponents, this would be handled by mail, sometimes over the preceding winter, sometimes just days in advance. For example, one of the earliest baseball letters here is dated 6 July 1866 from the Syracuse Arctics, located 30 miles to the west: "At a regular meeting of the Artics last evening, it was resolved to send your club a challenge. Game to be played on Thursday next week on your grounds. Our club will leave on the one-twenty train if the challenge is accepted." Similar correspondence is present from the Armory Base Ball Club of Ilion, Star Base Ball Club of Chittenango, Eckford Base Ball Club of Syracuse, Clipper Base Ball Club of Syracuse, Independent Base Ball Club of New York Mills, Amateur Base Ball Club of Auburn, and clubs in Rome, Canastota, Verona, Cazenovia, and Knoxboro, NY. The secretary of the Clifton Springs club boasted of their recent string of resounding victories on 16 June 1869, and in closing joked: "If you want to win, bring your umpire with you."

One 17 June 1867 challenge letter from the Utica Juniors went a bit further than most, listing their starting lineup and managing expectations: "We are a jr. club and we are not very large, not quite as large as some of you, as Ney tells us, but . . . we will treat you as well as we know how." They did not have their own grounds, or any means of reserving grounds: "We would rather have you come down in the morning as we can get better grounds than in the afternoon." Host clubs often provided banquets or other refreshments to visiting clubs. In August 1868, the Eckford club sent a formal "vote of thanks . . . for their kind and gentlemanly treatment of Eckfords during their stay in Oneida."

The highest of stakes was presented to the Atlantic Juniors by their crosstown rivals, the Oneida Base Ball Club, on 1 October 1866, which wanted to merge the two clubs: "If you are the victors, the two clubs will immediately consolidate under the name of the Atlantic Club of Oneida; and if we are the victors, the consolidation to be named the Oneida Club of Oneida." We don't know if that epic match was ever played, but the clubs remained separate the next year. The Atlantic club did not drop "Junior" from their name until the following June, and the Oneida club was still going the following August.

The exact definition of amateur was in flux by the late 1860s. A team in Bridgeport, NY accepted a challenge on 13 August 1869, but "there is some of our club is opposed to playing for money, and therefore we cannot accept your challenge to play for $50. . . . If you should want to bet money, there will be plenty of chances. We will also meet you at Manlius at any time you may choose and play for a ball."

In the first flowering of baseball as a mass entertainment, baseball supplies became a profitable industry. Chapin received a letter on 16 May 1867 from Edward H. Williams, a supplier in nearby Utica who described himself as an agent for "one of the largest base ball depots in New York." He enclosed his business card as a "manufacturer and dealer in hats and caps" as well as "fancy furs." Partner J.D. Williams wrote on 21 June 1867: "We did not receive your order untill last ev'g and it will be impossible for me to get them done by the time you want them. . . . I have got them all cut out and ready to make as soon as the girl gets time." A friend wrote from Clifton Springs on 16 July 1867: "I wish you would see Mr. Douglas and find out what he will charge for 6 Star balls."

The Atlantics undoubtedly took the inspiration for their name from the Atlantic Base Ball Club of Brooklyn, which went undefeated against the highest level of competition in 1865 and claimed the championship in 1866. However, this Atlantic nine was based in north-central New York state, many hours from New York City by train. Many of their local competition also took their inspiration from the high-class downstate teams, such as the Eckfords of Brooklyn. However, we find only one letter discussing the big city. Homer's younger brother Taylor Chapin (1849-1942) wrote on 1 June (year unknown) to describe his visit: "We went up to the Battery where the emigrants land, then to Central Park . . . up to Harlem Lane to see the fast horses . . . to the Olympic Theatre to see Humpty Dumpty." However, he did not take in a ballgame; on returning to Oneida, he noted that "base ball is quiet."

A friend named George R. Smith moved to Plymouth, Michigan and wrote on 8 April 1868 to boast that he had beaten the town's best billiard player on his first night out. He added: "The next thing was base ball. They asked me up to play with them the next day. . . . They have got a good club here. They have got as good a catcher as Sanford is. He used to catch in the best club in Detroit and he will get a ball if there is any gets pass the bat. . . . The left fielder is a mighty smart fellow. He has been with a circus for ten years." Smith wrote two weeks later to boast that his Red Rovers Base Ball Club was playing their Michigan neighbors from Northville for a $40 purse: "We will take the conceit out of them."

In addition to the correspondence, Secretary Chapin also wrote out a draft of the minutes to a May 1868 club meeting on the back of a jewelry circular, resolving to impose a ten-cent fine on "any member of the club that is not on the ground during practice days" or "any member of the club disputing the umpire during a match game."

The correspondence largely ends in 1870, but an outlying 1875 letter suggests that Chapin was still involved in baseball as he approached his thirties: "Will you please give me what information you can about Sullivan, who caught for the K.K.K.'s last season, in regard to his habits, playing abilities, and P.O. address."

In addition to the baseball content, this lot also contains additional correspondence from Chapin's friends going back to 1863, including several letters from William H. Overacre while enrolled at Western Union College and Military Academy in Illinois, who then enlisted in a Wisconsin artillery regiment and sent letters from training camp. Overacre died in the service in 1864, and his mother wrote to inform Chapin.

This archive offers an unusually detailed look at how the national game was organized and experienced in its very early years, before the first openly professional clubs were formed.

Exhibition Hours

Exhibition Hours

Aliquam vulputate ornare congue. Vestibulum maximus, libero in placerat faucibus, risus nisl molestie massa, ut maximus metus lectus vel lorem.