Sale 2686 - Lot 142

Price Realized: $ 1,100

Price Realized: $ 1,375

?Final Price Realized includes Buyer’s Premium added to Hammer Price

Estimate: $ 1,500 - $ 2,500

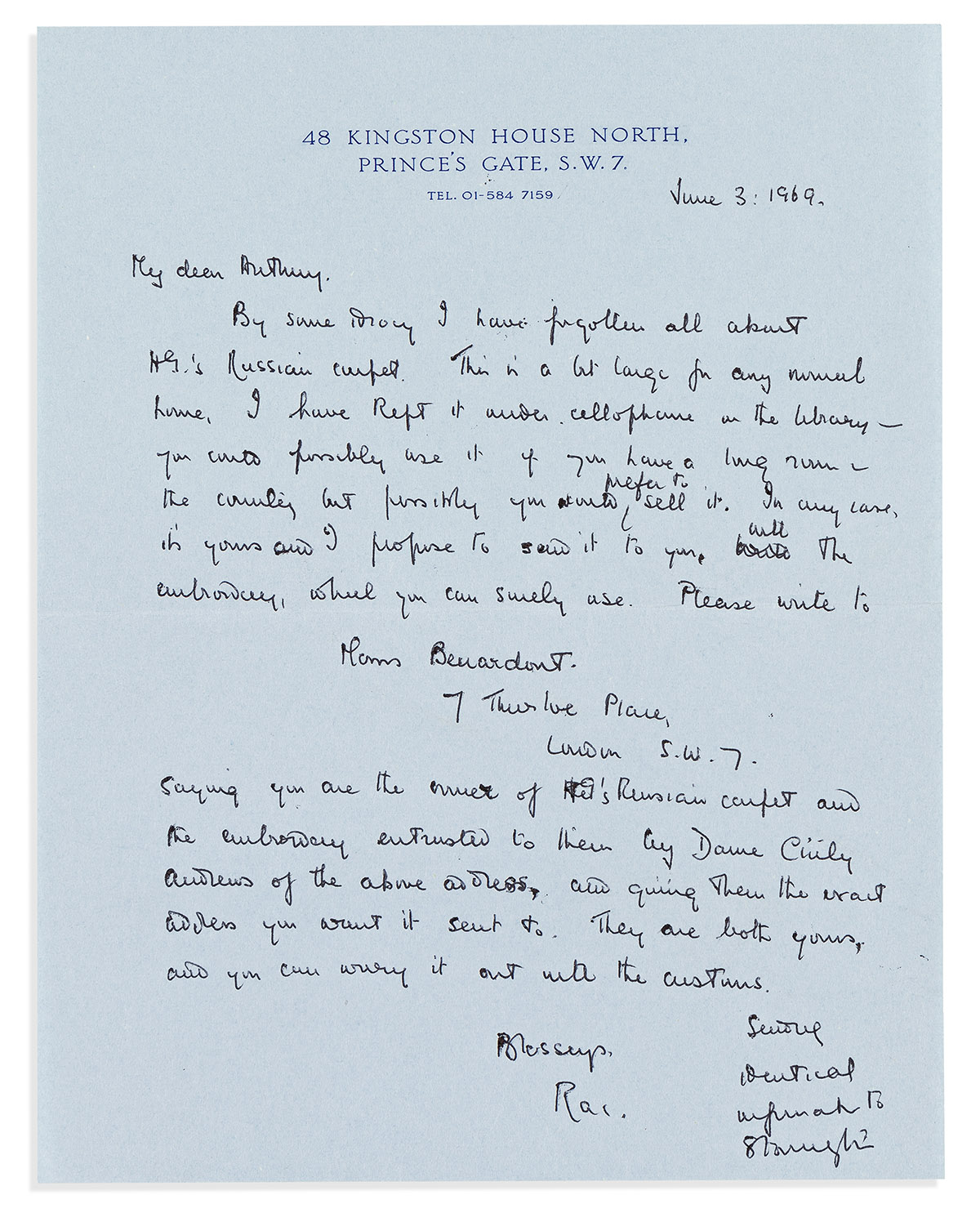

LITERARY AND SOMETIMES WRENCHING LETTERS TO THE SON SHE HAD WITH H.G. WELLS (WELLS, H.G.) REBECCA WEST. Archive of 12 letters Signed, "Rac" or "R," to her son Anthony West ("Dear Anthony" or "My dear Anthony" or "My dearest Anthony" or "My dear Comus" [Nickname]), including 4 ALsS and 8 TLsS, concerning an attempt to damage West's reputation by framing Anthony for a fictitious crime, mentioning encounters with or the work of several authors including Henry James, James Joyce, Gertrude Stein, Graham Greene, George Orwell, Winston Churchill, George Bernard Shaw, Wyndham Lewis, August Strindberg, T.S. Eliot, John Ruskin, Ken Kesey, Arnold Bennett, Alec Waugh, and John Lodwick, discussing her own work including Black Lamb and Grey Falcon (1941), A Train of Powder (1955), and various articles for magazines, discussing her alleged McCarthyism, expressing surprise at the negative portrayal of her in Anthony's fictionalized autobiography Heritage (1955), discussing newspaper strikes and the American proclivity of not reading, discussing the complex attitudes of the French toward the Arabs and the English toward the Irish, relating anecdotes from Wells's love affairs, describing the chaotic life at her country estate including the death of a cow due to "milk fever," complaining of Anthony's paltry inheritance from Wells and proposing certain ways of distributing her own estate. Together 35 pages, 4to or square 8vo; few early letters moderately soiled or torn but generally good condition. Vp, 1944-69

Additional Details

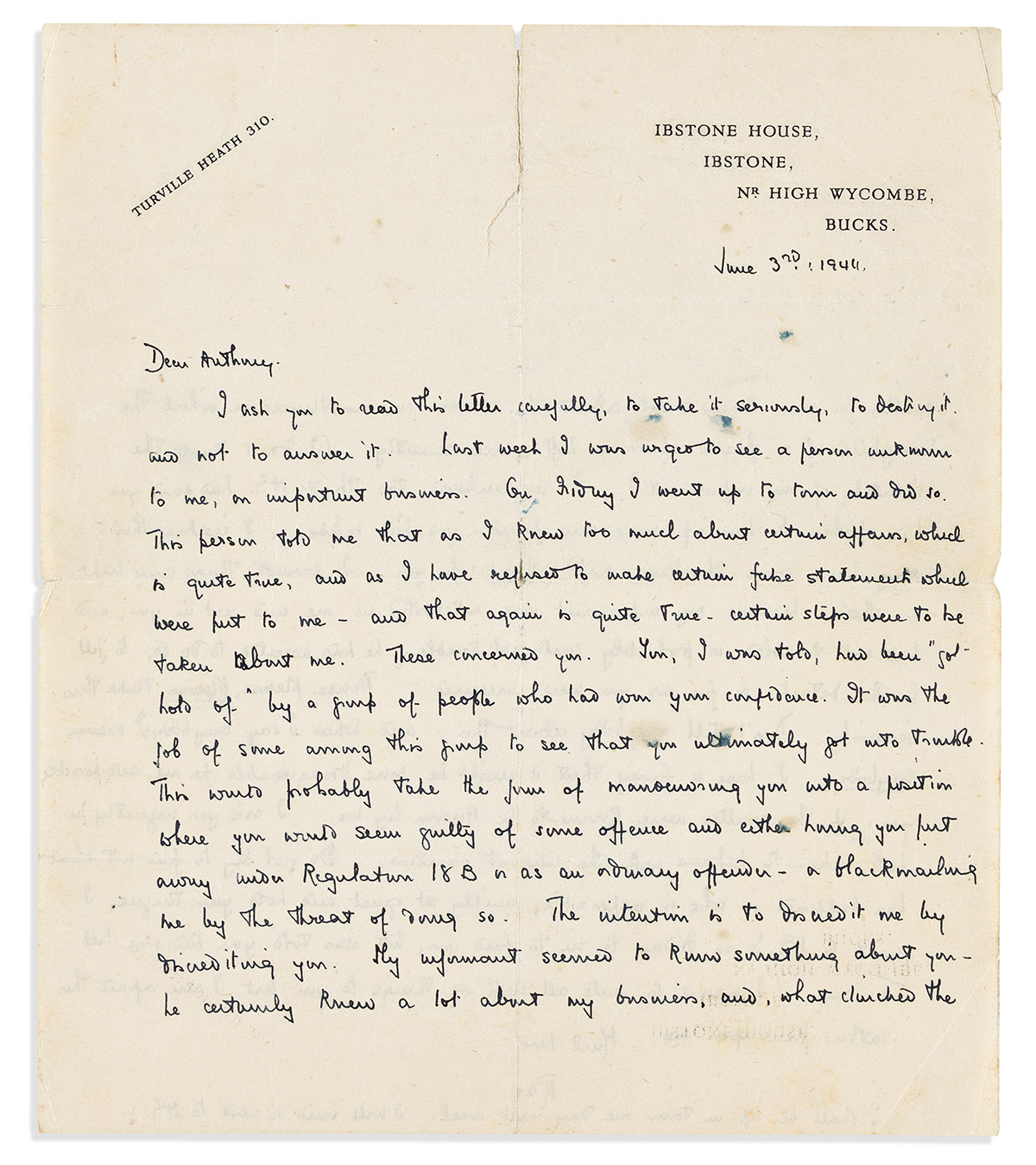

3 June 1944, ALS: "I ask you to read this letter carefully, to take it seriously, to destroy it, and not to answer it. Last week I was urged to see a person unknown to me, on important business. On Friday I went up to town and did so. This person told me that as I knew too much about certain affairs, which is quite true, and as I have refused to make certain fake statements which were put to me--and that again is quite true--certain steps were to be taken about me. These concerned you. You, I was told, had been 'got hold of' by a group of people who had won your confidence. It was the job of some among this group to see that you ultimately got into trouble. This would probably take the form of manoeuvering you into a position where you would seem guilty of some offence and either having you put away under Regulation 18B [empowering the Home Secretary to detain individuals deemed to be a threat] or as an ordinary offender--or blackmailing me by the threat of doing so. The intention is to discredit me by discrediting you. . . . I remembered . . . that H.G. had said you had spoken to him of some new friend you had made. I realize this may have some shocking implications for you--. . . . Please, please, please take this seriously. Do not tell anybody about this . . . ."

21 December 1954: ". . . I got pneumonia immediately on landing in New York in 1947, and when I was convalescent went down and did that lynching trial at Greenville [her article, "Opera in Greenville," was published in the June 6, 1947 issue of the New Yorker], and that must have been considerably easier than finding new ideas for Harper's. . . .

". . . I met the Henry James family on a boat once . . . . and I thought them not only Buckingham Palace, but Buckingham Palace in Queen Mary's time. . . .

"Thank you for doing something about John Lodwick. I admire his work enormously, though it doesn't settle down to anything definitive, and he is a tiresome person in a way. . . . He is a charming, slightly alcoholic, Graham Greenish character, on whom it weighs heavily that when he was a parachutist, dropped in France on one of those idiot secret missions, he made a mistake and got put on the carpet for it . . . .

"I haven't seen what the minor art critics say about my Picasso essay ["Picasso: The Images and Insights of Genius" in the October 1954 issue of Harper's Bazaar] . . . . I am used to getting a bad press. Two years ago the Sunday Times came to me and asked me to do a series of four articles on anything, to fill up a gap. I said I could do them four articles . . . concerning people being eased into the Civil Service without passing examinations because they were C[ommunist]P[arty; the articles were published in the Times between March and April 1953]. Not a word in my articles concerned McCarthy's investigations . . . . Ever since then there has been a whispering campaign against me as a McCarthyite, and all the horrid little pansies make venomous allusions to me. . . . I am thoroughly tired of England, and I do not care what anybody thinks of me over here. . . .

"I was a little alarmed at seeing your article on Churchill, in case it means that the Old Man is doing one of his nautch girl dances in front of you. Do always remember that he is an inhuman little humbug and sadist, who takes people up for the purpose of dropping them when they feel most secure. He is now demented . . . . [H]e has destroyed the value of the Evening Standard during the last few years--. . . he has tried to make it a tabloid and has brought down the circulation to almost nothing . . . . It is frightening to think that he held up atomic development for years by going into a fight with Lord Cherwell, who perhaps knows more about it. . . ."

15 May 1955: ". . . I am getting such charming reviews of A Train of Powder from the provincial American newspapers--such a pleasant contrast with what I get in this country. I never get a press-cutting that is not an insult. . . . I am dreading the publication of A Train of Powder here on June 4th."

27 November 1961: ". . . What worried me about Heritage [Anthony's fictionalized autobiography, published in 1955] . . . was the feeling behind the book. A great deal of the book read to me as if you had not written it, but I did recognise that even if you had not, only a deep resentment would account for the publication. The idea of this feeling not only distressed me but puzzled me . . . until Kitty [Anthony's first wife, Katharine Church] told me various things which made it clearer. . . . [S]he told me . . . you had often told her . . . that I had sent you to school when you were two years old, because your presence was an embarrassment to me, and that you had hardly seen H.G. till you were 11 . . . the idea being that I had kept you from him till then.

". . . We moved . . . to a very nice house in Leigh-on-Sea, when you were two and a half or more--I know that it was early spring and I remember also that H.G. came down when I was moving in . . . . and after dinner he whispered in my ear that I must tell nobody but there had been a Russian Revolution. But unfortunately very shortly after we got into the house we were on the balcony one day and a plane went past so low that we could see the pilot, and it was the first German plane to fly over England. Subsequently we had . . . about six plane raids . . . . I was very anxious about your safety . . . . As we got into the autumn of 1917 the raiders came by night, and there was a naval gun put on to the cliff in front of our house. It was quite impossible . . . . I therefore sent you to Miss Hillyard's school at Early's Court, because . . . the school had solid cellars. . . . I can assure you that from first to last your illegitimacy had nothing to do with your being sent to school, nor had I the slightest desire to disembarrass myself of you. . . .

". . . You can't be so hopelessly stupid that you think that I, given my particular make-up, would have chosen to have an illegitimate child. I had a love-affair with H.G., and I loved him then as I was always to love him, on the understanding that he would not give me a child, a promise he wantonly broke simply because he wanted the panache of having a child by the infant prodigy of the day. I was appalled by the situation when it arose, the more so by the way that H.G. handled it . . . . I do not blame you for being more conscious of your own sufferings; but as a factual view of the situation surely you need not have interpreted as neglect on my part what were the hardships of our common victimisation by a raging egotist who loved us both and at the same time did not even faintly care what happen[ed] to either of us. . . ."

16 March 1963: ". . . I don't think it was possible for England to create a community of interest between rulers and ruled, nor that there is any analogy between Ireland and the rest of the Commonwealth. The only thing that connected England and Ireland was that England had to possess Ireland in order to prevent it from being used as a base by England's enemies. The English and the Irish were of different and antipathetic religions, there was no way by which England could develop the resources of Ireland because there were practically none, the past had left a number of lower-class Irishmen who Englishmen could no more take as their equal than white Americans at the same period could take Negroes. . . ."

31 May 1969: ". . . I strongly objected to H.G. not treating you on an absolute equality with Gip and Frank [his children George Philip and Frank Richard by his wife "Jane" Amy Catherine Robbins], and resented the fact that for a long time he made no provision for you beyond leaving me £2,000 in a codicil to his will, which was even then a small sum. . . . He simply could not bear to do anything for you, first because he had this superstitious fear of Jane, and he had a curious feeling that she alone had the right to spend this money--and spend she did. . . ."

17 June 1969: ". . . I have attended a meeting of the Wells Society which is held in the Electrical Engineers Common Room over the way at the Imperial College, there is a wonderful character called Mimi May who runs Spare House as a boarding-house (vegetarian) and is madly in love with H.G.'s ghost. . . ."

In the September 19, 1912 issue of the feminist weekly, The Freewoman, Rebecca West responded to H.G. Wells's new novel Marriage by attacking the author, writing that he "is the Old Maid among novelists; even the sex obsession that lay clotted on Ann Veronica . . . like cold white sauce was merely Old Maids' mania, the reaction towards the flesh of a mind too long absorbed in airships . . . ." Wells found this provocation too enticing to resist, inviting her to visit and discuss her review of his book. The result of the meeting was a decade-long love affair and a son, Anthony--mostly with the knowledge if not consent of Wells's wife, Amy Catherine Robbins. The pet names they used for each other were not sweet, but feral: "Jaguar" for Wells and "Panther" for West.

Provenance: Rebecca West; thence by descent to Anthony West; thence by descent to Edmund West; thence by private sale to current owner.

21 December 1954: ". . . I got pneumonia immediately on landing in New York in 1947, and when I was convalescent went down and did that lynching trial at Greenville [her article, "Opera in Greenville," was published in the June 6, 1947 issue of the New Yorker], and that must have been considerably easier than finding new ideas for Harper's. . . .

". . . I met the Henry James family on a boat once . . . . and I thought them not only Buckingham Palace, but Buckingham Palace in Queen Mary's time. . . .

"Thank you for doing something about John Lodwick. I admire his work enormously, though it doesn't settle down to anything definitive, and he is a tiresome person in a way. . . . He is a charming, slightly alcoholic, Graham Greenish character, on whom it weighs heavily that when he was a parachutist, dropped in France on one of those idiot secret missions, he made a mistake and got put on the carpet for it . . . .

"I haven't seen what the minor art critics say about my Picasso essay ["Picasso: The Images and Insights of Genius" in the October 1954 issue of Harper's Bazaar] . . . . I am used to getting a bad press. Two years ago the Sunday Times came to me and asked me to do a series of four articles on anything, to fill up a gap. I said I could do them four articles . . . concerning people being eased into the Civil Service without passing examinations because they were C[ommunist]P[arty; the articles were published in the Times between March and April 1953]. Not a word in my articles concerned McCarthy's investigations . . . . Ever since then there has been a whispering campaign against me as a McCarthyite, and all the horrid little pansies make venomous allusions to me. . . . I am thoroughly tired of England, and I do not care what anybody thinks of me over here. . . .

"I was a little alarmed at seeing your article on Churchill, in case it means that the Old Man is doing one of his nautch girl dances in front of you. Do always remember that he is an inhuman little humbug and sadist, who takes people up for the purpose of dropping them when they feel most secure. He is now demented . . . . [H]e has destroyed the value of the Evening Standard during the last few years--. . . he has tried to make it a tabloid and has brought down the circulation to almost nothing . . . . It is frightening to think that he held up atomic development for years by going into a fight with Lord Cherwell, who perhaps knows more about it. . . ."

15 May 1955: ". . . I am getting such charming reviews of A Train of Powder from the provincial American newspapers--such a pleasant contrast with what I get in this country. I never get a press-cutting that is not an insult. . . . I am dreading the publication of A Train of Powder here on June 4th."

27 November 1961: ". . . What worried me about Heritage [Anthony's fictionalized autobiography, published in 1955] . . . was the feeling behind the book. A great deal of the book read to me as if you had not written it, but I did recognise that even if you had not, only a deep resentment would account for the publication. The idea of this feeling not only distressed me but puzzled me . . . until Kitty [Anthony's first wife, Katharine Church] told me various things which made it clearer. . . . [S]he told me . . . you had often told her . . . that I had sent you to school when you were two years old, because your presence was an embarrassment to me, and that you had hardly seen H.G. till you were 11 . . . the idea being that I had kept you from him till then.

". . . We moved . . . to a very nice house in Leigh-on-Sea, when you were two and a half or more--I know that it was early spring and I remember also that H.G. came down when I was moving in . . . . and after dinner he whispered in my ear that I must tell nobody but there had been a Russian Revolution. But unfortunately very shortly after we got into the house we were on the balcony one day and a plane went past so low that we could see the pilot, and it was the first German plane to fly over England. Subsequently we had . . . about six plane raids . . . . I was very anxious about your safety . . . . As we got into the autumn of 1917 the raiders came by night, and there was a naval gun put on to the cliff in front of our house. It was quite impossible . . . . I therefore sent you to Miss Hillyard's school at Early's Court, because . . . the school had solid cellars. . . . I can assure you that from first to last your illegitimacy had nothing to do with your being sent to school, nor had I the slightest desire to disembarrass myself of you. . . .

". . . You can't be so hopelessly stupid that you think that I, given my particular make-up, would have chosen to have an illegitimate child. I had a love-affair with H.G., and I loved him then as I was always to love him, on the understanding that he would not give me a child, a promise he wantonly broke simply because he wanted the panache of having a child by the infant prodigy of the day. I was appalled by the situation when it arose, the more so by the way that H.G. handled it . . . . I do not blame you for being more conscious of your own sufferings; but as a factual view of the situation surely you need not have interpreted as neglect on my part what were the hardships of our common victimisation by a raging egotist who loved us both and at the same time did not even faintly care what happen[ed] to either of us. . . ."

16 March 1963: ". . . I don't think it was possible for England to create a community of interest between rulers and ruled, nor that there is any analogy between Ireland and the rest of the Commonwealth. The only thing that connected England and Ireland was that England had to possess Ireland in order to prevent it from being used as a base by England's enemies. The English and the Irish were of different and antipathetic religions, there was no way by which England could develop the resources of Ireland because there were practically none, the past had left a number of lower-class Irishmen who Englishmen could no more take as their equal than white Americans at the same period could take Negroes. . . ."

31 May 1969: ". . . I strongly objected to H.G. not treating you on an absolute equality with Gip and Frank [his children George Philip and Frank Richard by his wife "Jane" Amy Catherine Robbins], and resented the fact that for a long time he made no provision for you beyond leaving me £2,000 in a codicil to his will, which was even then a small sum. . . . He simply could not bear to do anything for you, first because he had this superstitious fear of Jane, and he had a curious feeling that she alone had the right to spend this money--and spend she did. . . ."

17 June 1969: ". . . I have attended a meeting of the Wells Society which is held in the Electrical Engineers Common Room over the way at the Imperial College, there is a wonderful character called Mimi May who runs Spare House as a boarding-house (vegetarian) and is madly in love with H.G.'s ghost. . . ."

In the September 19, 1912 issue of the feminist weekly, The Freewoman, Rebecca West responded to H.G. Wells's new novel Marriage by attacking the author, writing that he "is the Old Maid among novelists; even the sex obsession that lay clotted on Ann Veronica . . . like cold white sauce was merely Old Maids' mania, the reaction towards the flesh of a mind too long absorbed in airships . . . ." Wells found this provocation too enticing to resist, inviting her to visit and discuss her review of his book. The result of the meeting was a decade-long love affair and a son, Anthony--mostly with the knowledge if not consent of Wells's wife, Amy Catherine Robbins. The pet names they used for each other were not sweet, but feral: "Jaguar" for Wells and "Panther" for West.

Provenance: Rebecca West; thence by descent to Anthony West; thence by descent to Edmund West; thence by private sale to current owner.

Exhibition Hours

Exhibition Hours

Aliquam vulputate ornare congue. Vestibulum maximus, libero in placerat faucibus, risus nisl molestie massa, ut maximus metus lectus vel lorem.