Sale 2486 - Lot 410

Price Realized: $ 8,500

Price Realized: $ 10,625

?Final Price Realized includes Buyer’s Premium added to Hammer Price

Estimate: $ 8,000 - $ 12,000

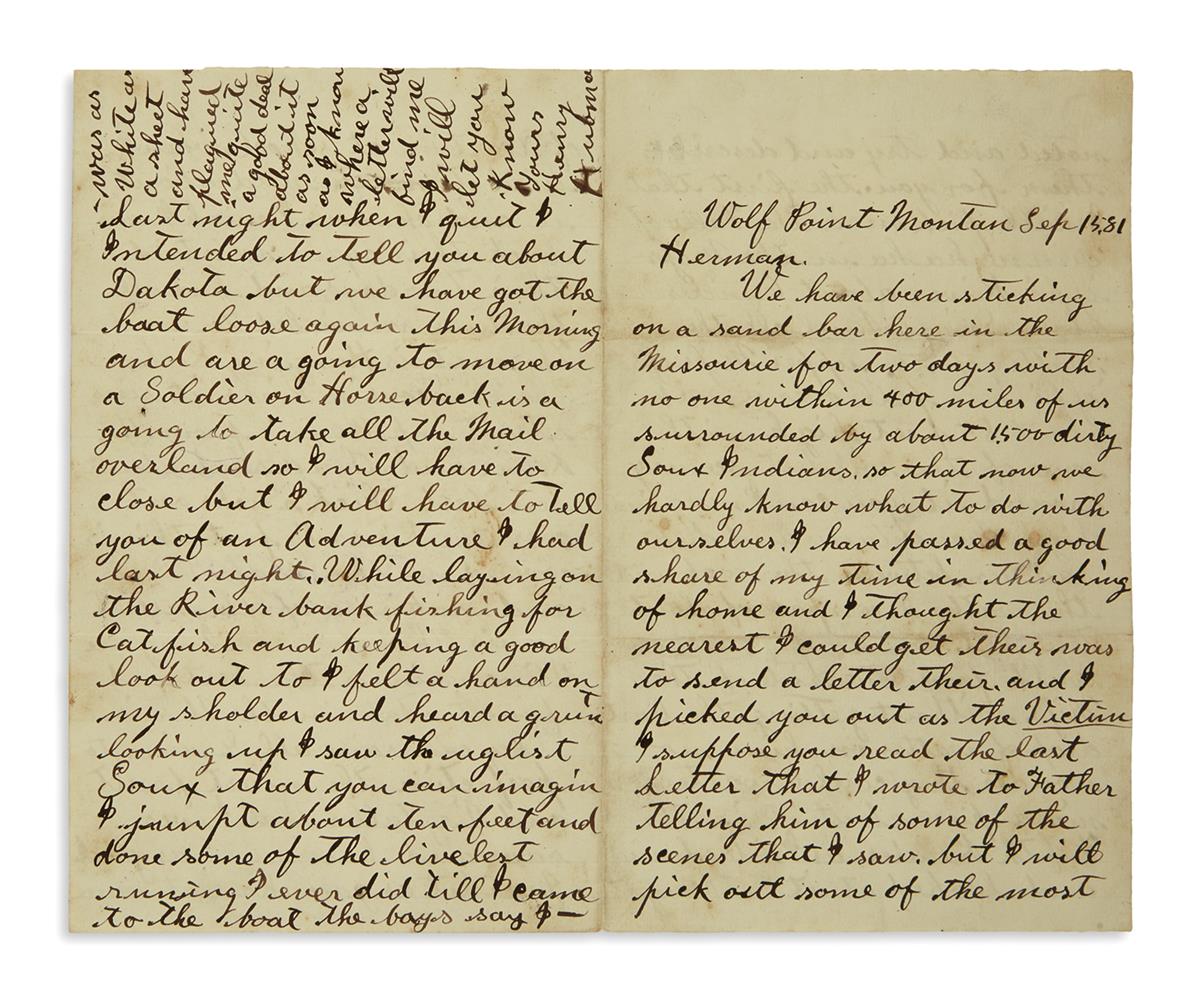

(WEST.) Correspondence of Henry Hubman, Iowa medical student / Montana Indian fighter / deserter in Canada. 41 Autograph Letters Signed from Henry Hubman to his parents Jacob and Margaret Hubman and to brothers Herman, George and Frederick Hubman, plus 5 other related letters to the Hubmans; condition generally strong, many letters with original stamped and postmarked envelopes. Vp, 1880-89

Additional Details

The troubled life of a fugitive soldier comes alive in these letters. Henry Hubman (1860-1927) was raised in Fayette, Seneca County, NY and left home for medical school in Keokuk, IA. There, on the verge of graduation, he suddenly enlisted in the army, apparently to escape a relationship with a young woman. In July 1881, he began service in the 18th Infantry Regiment, and was soon sent to Montana on the western frontier, just five years after Little Bighorn. Military life did not agree with him, and he deserted in February 1883 in a premeditated act. He fled to Canada and settled just across the border in Emerson, Manitoba, where he married and raised a family. He apparently never returned to the United States.

The 5 earliest letters in this collection were written as a medical student at Keokuk's College of Physicians and Surgeons of the Upper Mississippi (since absorbed into the University of Iowa system). The first one, dated 20 October 1880, complains of the faculty: "The professors are all good except the one on surgery. He had his first operation yesterday, and gave his patient so mutch chloroform that he died on the table, a bad beginning." On 28 February a classmate sent a letter home: "Henry is missing." An exhaustive search on foot and by the new miracle of telephony yielded no clues. He had passed his examinations, was expecting $100, but had apparently "skipped town." The Hubmans received a letter the next year from May Scott, who asserted that she was "the young lady he was engaged to when he boarded in Keokuk" and asked them to "forgive him and help him now out of his dark and lonely place."

5 months after his disappearance, Henry wrote to his father from a fort in Columbus, OH: "I hate to tell you what I am at, for I know it will grieve you and I am sorry, but can not alter it now." He had enlisted into the Army on a dare, and soon regretted his choice: "A man stands a very slim chance to get through with five years on the front." He later admitted (19 November) that continuous heavy drinking led to his rash decision. September found him in Montana; he would spend most of the next 18 months based out of Fort Assiniboine near the Canadian border.

18 letters are written from various locations in Montana during this period, and include frequent discussion of Hubman's great discomfort with American Indians. On 15 September 1881 he wrote "While laying on the river bank fishing . . . I felt a hand on my sholder and heard a grunt. Looking up I saw the uglist Soux that you can imagine. I jumpt about ten feet and done some of the livelest running I ever did till I came to the boat, the boys say I was as white as a sheet." On 1 October, he told his brother "We have lots of the ugly cusses all around us. They are about as mean and dirty an animal as you can imagine and think no more of killing a white man or another Indian than you would of a fly. When they kill a soldier they eat his heart and liver, they say it makes them brave." 5 days later he was on the trail: "Father we are out on the Canadian line after 9000 Cree Indians. We are 200 strong and are now within 3 miles of them and are a going to pitch into them tomorrow morning. . . . Some Cree may want to send me to the Happy Hunting Ground but he will have to be sharper than I am. We have slept with 60 catridges around us and our gun along side of us for 4 days. The Crees came over here to fight the Assinobone Indians and made a mistake and killed a lot of white settlers on the Milk River." The prospect of torture haunted him, and he wrote on 27 December 1881: "I have studied medicine long enough to learn that cyanite of potasium is a very good feed, and I always keep some about me in case of capture by Indians, for I am not very brave and think I would flinch some if they began to skin me alive, which is one of their favorite amusements when they have prisoners." Wolves, grizzly bears, rattlesnakes, and buffalo are all encountered.

On 1 March 1882, Hubman begs his father for assistance in escaping his military duty, and notes "I would rather take my chances at desertion than stay the balance of my 5 years in the Army." On 2 June he risked committing his plan to paper in a letter to his brother: "Two of the boys besides myself are going to try and make Canada after we are paid in September. It is pretty risky piece of Business as we have to go through 200 miles of hostile Cree Indian country, but I am willing to risk anything to get out of this hole." He enclosed a gift of moccasins (not included with this lot): "They belonged to the greatest foe of the white man in Montana, Two Bear by name. Keep them and whenever you look at them think of your unfortunate brother and try and shun his ways." His last letter from the service was dated 12 February 1883; research shows that he deserted on 1 June.

The correspondence concludes with 15 letters written from Hubman's new home in Emerson, Manitoba, describing his new Canadian wife and their children, as well as the cold and poverty they endured, 1885-89. These letters are not quite as action-packed as the Montana letters, though on 11 July 1887 he notes that "the half-breeds north of us have murdered four settlers." The collection as a whole tells a dramatic Western story in vivid language; we can share only a tiny fraction here. Extensive notes on the Montana letters are available upon request.

The 5 earliest letters in this collection were written as a medical student at Keokuk's College of Physicians and Surgeons of the Upper Mississippi (since absorbed into the University of Iowa system). The first one, dated 20 October 1880, complains of the faculty: "The professors are all good except the one on surgery. He had his first operation yesterday, and gave his patient so mutch chloroform that he died on the table, a bad beginning." On 28 February a classmate sent a letter home: "Henry is missing." An exhaustive search on foot and by the new miracle of telephony yielded no clues. He had passed his examinations, was expecting $100, but had apparently "skipped town." The Hubmans received a letter the next year from May Scott, who asserted that she was "the young lady he was engaged to when he boarded in Keokuk" and asked them to "forgive him and help him now out of his dark and lonely place."

5 months after his disappearance, Henry wrote to his father from a fort in Columbus, OH: "I hate to tell you what I am at, for I know it will grieve you and I am sorry, but can not alter it now." He had enlisted into the Army on a dare, and soon regretted his choice: "A man stands a very slim chance to get through with five years on the front." He later admitted (19 November) that continuous heavy drinking led to his rash decision. September found him in Montana; he would spend most of the next 18 months based out of Fort Assiniboine near the Canadian border.

18 letters are written from various locations in Montana during this period, and include frequent discussion of Hubman's great discomfort with American Indians. On 15 September 1881 he wrote "While laying on the river bank fishing . . . I felt a hand on my sholder and heard a grunt. Looking up I saw the uglist Soux that you can imagine. I jumpt about ten feet and done some of the livelest running I ever did till I came to the boat, the boys say I was as white as a sheet." On 1 October, he told his brother "We have lots of the ugly cusses all around us. They are about as mean and dirty an animal as you can imagine and think no more of killing a white man or another Indian than you would of a fly. When they kill a soldier they eat his heart and liver, they say it makes them brave." 5 days later he was on the trail: "Father we are out on the Canadian line after 9000 Cree Indians. We are 200 strong and are now within 3 miles of them and are a going to pitch into them tomorrow morning. . . . Some Cree may want to send me to the Happy Hunting Ground but he will have to be sharper than I am. We have slept with 60 catridges around us and our gun along side of us for 4 days. The Crees came over here to fight the Assinobone Indians and made a mistake and killed a lot of white settlers on the Milk River." The prospect of torture haunted him, and he wrote on 27 December 1881: "I have studied medicine long enough to learn that cyanite of potasium is a very good feed, and I always keep some about me in case of capture by Indians, for I am not very brave and think I would flinch some if they began to skin me alive, which is one of their favorite amusements when they have prisoners." Wolves, grizzly bears, rattlesnakes, and buffalo are all encountered.

On 1 March 1882, Hubman begs his father for assistance in escaping his military duty, and notes "I would rather take my chances at desertion than stay the balance of my 5 years in the Army." On 2 June he risked committing his plan to paper in a letter to his brother: "Two of the boys besides myself are going to try and make Canada after we are paid in September. It is pretty risky piece of Business as we have to go through 200 miles of hostile Cree Indian country, but I am willing to risk anything to get out of this hole." He enclosed a gift of moccasins (not included with this lot): "They belonged to the greatest foe of the white man in Montana, Two Bear by name. Keep them and whenever you look at them think of your unfortunate brother and try and shun his ways." His last letter from the service was dated 12 February 1883; research shows that he deserted on 1 June.

The correspondence concludes with 15 letters written from Hubman's new home in Emerson, Manitoba, describing his new Canadian wife and their children, as well as the cold and poverty they endured, 1885-89. These letters are not quite as action-packed as the Montana letters, though on 11 July 1887 he notes that "the half-breeds north of us have murdered four settlers." The collection as a whole tells a dramatic Western story in vivid language; we can share only a tiny fraction here. Extensive notes on the Montana letters are available upon request.

Exhibition Hours

Exhibition Hours

Aliquam vulputate ornare congue. Vestibulum maximus, libero in placerat faucibus, risus nisl molestie massa, ut maximus metus lectus vel lorem.