Sale 2687 - Lot 257

Price Realized: $ 10,000

Price Realized: $ 12,500

?Final Price Realized includes Buyer’s Premium added to Hammer Price

Estimate: $ 4,000 - $ 6,000

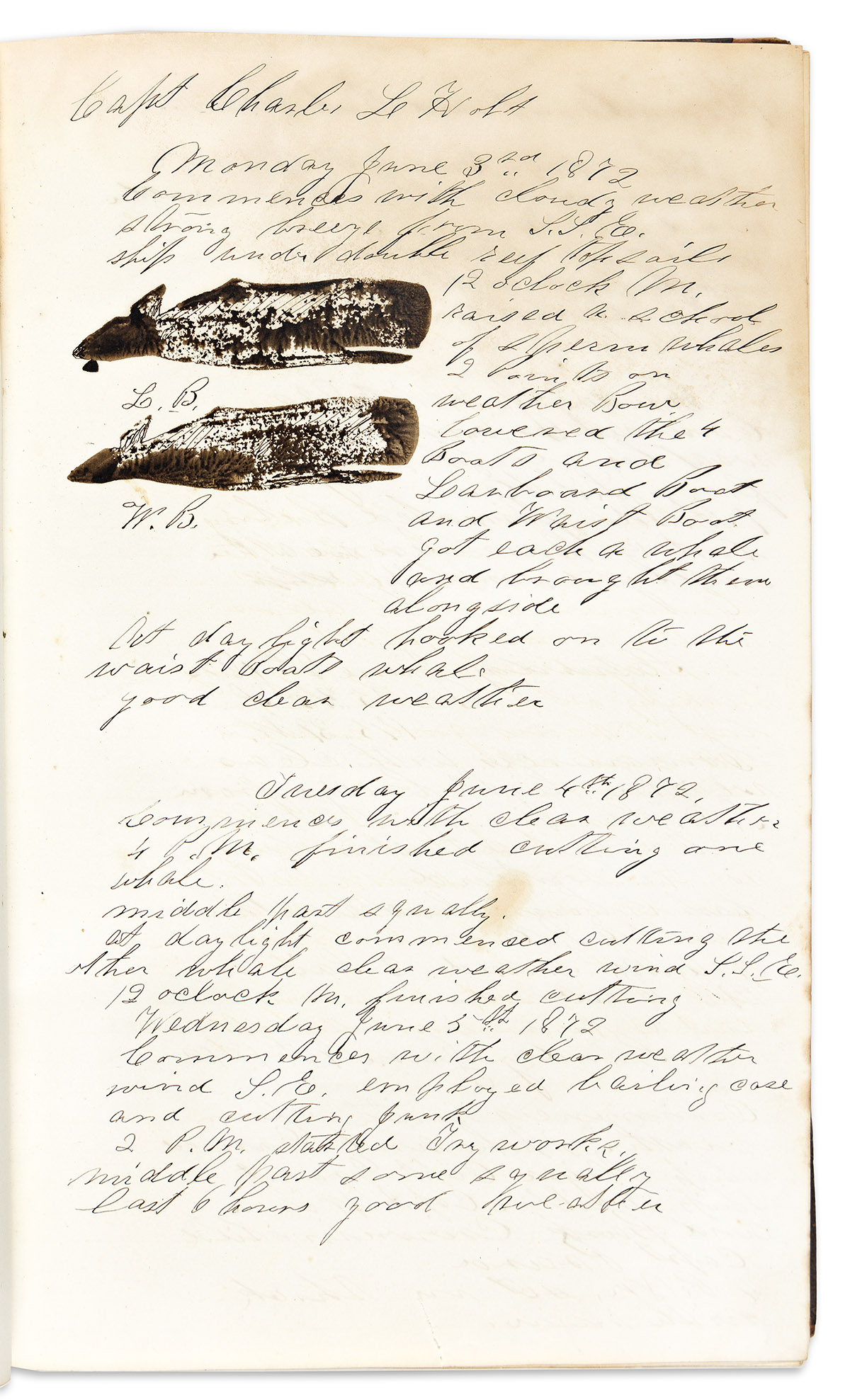

(WHALING.) Journal of the whaling ship Hunter out of New Bedford, including a long search for six whalemen lost at sea. [270] manuscript pages marked with 46 whale stamps. Folio, 13½ x 8¼ inches, original ½ calf over marbled boards, dampstained and paper coming detached; dampstaining to contents; Taber Brothers manufacturer's tag. Various places, 26 September 1871 to 13 July 1875

Additional Details

The bark Hunter sailed out of New Bedford, MA under Captain Charles L. Holt in September 1871, spent almost 4 years in the Pacific, and returned in July 1875. Starbuck's "History of the American Whale Fishery" shows that they brought home 2700 barrels of sperm oil, the most of any American whaler that year; plus 1100 barrels of whale oil. You might call this a very successful voyage--except for a whaleboat which vanished with all six crew members during a chase.

Let us begin with the mystery of the lost whaleboat, 21 months into the voyage. The bulk of the log is written by Third Mate John McInnis (circa 1846-1899), but Captain Holt announces that he is taking over the logbook from 8 to 13 June 1873, writing much longer entries in his more refined hand. He describes a disastrous overnight 8-9 June hunt in much more detail than in the preceding entries: "I lowered in the starboard boat & took 4th Mate to steer me as one of our boatsteerers was sick . . . & told him to keep run of the fast boat & keep the ship close to him. . . . Larboard boat's whale dead & he had his sail out so the ship could see him." The next day the captain and the crew on board the ship lost sight of the "fast boat" and spent days searching for it: "Since loosing the boat, we have kept good men at mast heads day & night on the lookout & two good lights all night" (11 June). Finally he lists the six missing men on 13 June, and on 15 June the log notes: "We have been all over the ground where we lost the boat, but as yet have seen no signs of her, so last part, gave it up & started across the ground steering E.N.E. for Savage Island." McInnis resumes writing on 22 June (providing his name for the first and only time).

The leader of the lost boat, Chief Mate George M. Remington (1841-1873) of Centreville, RI, has a gravestone which records him "lost at sea" on 9 June 1873. The lost whaleboat is discussed briefly in the Boston Post of 4 February 1874; apparently the whale with the Hunter's harpoon still attached was found by another ship a couple of days after the boat's disappearance.

The loss of the whaleboat was not the only drama on this long voyage. Whaling crews were an unruly bunch. The first excitement in this log was just two days in: "Found one stowaway, by name John Butler." Then on 4 October, "John H. Amey, blacksmith, taken insane. Tryed to cut one of the men with a knife. We put him in irons." On 13 October, the ship stopped at Graciosa in the Azores and "landed Manuel Silva . . . to have 24 hours liberty"; he was presumed to have deserted but as they left they saw that "Silvas's trunk was there on the beach and his mother was there to bid him goodbye, and the policeman stated that there was no compulsion about it." While in port at the Bay of Islands in New Zealand, "one watch on shore on liberty. David Wilson & Frederic Sleeper deserted, but were brought back" (24 March 1872). The same pair re-deserted eight days later, but were apparently re-captured before the ship left port. At the next port, Wilson jumped ship again. While being rowed back to the Hunter, "Wilson commenced to abuse the Capt and the rest of the crew in the boat, calling the Capt all the sons of bitches he could lay his tongue to, also calling him all the other bad names he could think of. He then commenced to kick the natives that the Capt had hired. . . . The Capt took hold of him and put him in the bottom of the boat and slapped his face for him. He then remained quiet until he got on board, when he commenced his abusive language again, and we put him in irons" (19 August 1872). The next day, a steward was kicked and slapped by the Captain for "giving away molasses by the quart bottle full to the natives, also for taking cloth and bread out of the ship and selling it to the natives." Frederic Sleeper deserted again, and was caught a third time, on 11 November 1872.

Despite the drama, the Hunter was effective at hunting whales. The first whale spotting (and first whale stamp) was on 21 October 1871. One whale stamp on 18 April 1872 is crossed out, with the note "Proved to be a jumper." The log's whaling entries sometimes offer a narrative of the hunt: "Waist and bow boats got loose from the whale. 6 p.m., larboard boat got stove but not so bad but they could hold on the whale" (18 May 1873). The ship returned to port on 13 July 1875. Following the final entry are two pages of notes in a later hand on the Hunter's next voyage, including their crew list from September 1875. Laid in is the original 27 September 1871 crew list, in pencil on a small slip of paper.

Provenance: gift from Benjamin Baker as executor and unofficial historian of the estate of whaling magnate Jonathan Bourne (the Hunter's owner) to Cora Lester Holt of North Dighton (daughter of Captain Charles L. Holt), per a 4 July 1923 letter laid in.

Let us begin with the mystery of the lost whaleboat, 21 months into the voyage. The bulk of the log is written by Third Mate John McInnis (circa 1846-1899), but Captain Holt announces that he is taking over the logbook from 8 to 13 June 1873, writing much longer entries in his more refined hand. He describes a disastrous overnight 8-9 June hunt in much more detail than in the preceding entries: "I lowered in the starboard boat & took 4th Mate to steer me as one of our boatsteerers was sick . . . & told him to keep run of the fast boat & keep the ship close to him. . . . Larboard boat's whale dead & he had his sail out so the ship could see him." The next day the captain and the crew on board the ship lost sight of the "fast boat" and spent days searching for it: "Since loosing the boat, we have kept good men at mast heads day & night on the lookout & two good lights all night" (11 June). Finally he lists the six missing men on 13 June, and on 15 June the log notes: "We have been all over the ground where we lost the boat, but as yet have seen no signs of her, so last part, gave it up & started across the ground steering E.N.E. for Savage Island." McInnis resumes writing on 22 June (providing his name for the first and only time).

The leader of the lost boat, Chief Mate George M. Remington (1841-1873) of Centreville, RI, has a gravestone which records him "lost at sea" on 9 June 1873. The lost whaleboat is discussed briefly in the Boston Post of 4 February 1874; apparently the whale with the Hunter's harpoon still attached was found by another ship a couple of days after the boat's disappearance.

The loss of the whaleboat was not the only drama on this long voyage. Whaling crews were an unruly bunch. The first excitement in this log was just two days in: "Found one stowaway, by name John Butler." Then on 4 October, "John H. Amey, blacksmith, taken insane. Tryed to cut one of the men with a knife. We put him in irons." On 13 October, the ship stopped at Graciosa in the Azores and "landed Manuel Silva . . . to have 24 hours liberty"; he was presumed to have deserted but as they left they saw that "Silvas's trunk was there on the beach and his mother was there to bid him goodbye, and the policeman stated that there was no compulsion about it." While in port at the Bay of Islands in New Zealand, "one watch on shore on liberty. David Wilson & Frederic Sleeper deserted, but were brought back" (24 March 1872). The same pair re-deserted eight days later, but were apparently re-captured before the ship left port. At the next port, Wilson jumped ship again. While being rowed back to the Hunter, "Wilson commenced to abuse the Capt and the rest of the crew in the boat, calling the Capt all the sons of bitches he could lay his tongue to, also calling him all the other bad names he could think of. He then commenced to kick the natives that the Capt had hired. . . . The Capt took hold of him and put him in the bottom of the boat and slapped his face for him. He then remained quiet until he got on board, when he commenced his abusive language again, and we put him in irons" (19 August 1872). The next day, a steward was kicked and slapped by the Captain for "giving away molasses by the quart bottle full to the natives, also for taking cloth and bread out of the ship and selling it to the natives." Frederic Sleeper deserted again, and was caught a third time, on 11 November 1872.

Despite the drama, the Hunter was effective at hunting whales. The first whale spotting (and first whale stamp) was on 21 October 1871. One whale stamp on 18 April 1872 is crossed out, with the note "Proved to be a jumper." The log's whaling entries sometimes offer a narrative of the hunt: "Waist and bow boats got loose from the whale. 6 p.m., larboard boat got stove but not so bad but they could hold on the whale" (18 May 1873). The ship returned to port on 13 July 1875. Following the final entry are two pages of notes in a later hand on the Hunter's next voyage, including their crew list from September 1875. Laid in is the original 27 September 1871 crew list, in pencil on a small slip of paper.

Provenance: gift from Benjamin Baker as executor and unofficial historian of the estate of whaling magnate Jonathan Bourne (the Hunter's owner) to Cora Lester Holt of North Dighton (daughter of Captain Charles L. Holt), per a 4 July 1923 letter laid in.

Exhibition Hours

Exhibition Hours

Aliquam vulputate ornare congue. Vestibulum maximus, libero in placerat faucibus, risus nisl molestie massa, ut maximus metus lectus vel lorem.