Sale 2546 - Lot 256

Price Realized: $ 1,500

Price Realized: $ 1,875

?Final Price Realized includes Buyer’s Premium added to Hammer Price

Estimate: $ 1,500 - $ 2,500

(WORLD WAR TWO.) McGonigle, William A. Diary of an airman who survived his 35 bomber sorties. [63] manuscript diary pages, plus a 2-page manuscript mission list and 7 pages of manuscript poetry. 8vo, original plain cloth, with name stamped on front board, minor wear; minimal wear to contents; typed censor's note tipped to front pastedown. Vp, June 1944 to February 1945

Additional Details

A diary of incredibly hazardous bomber duty in the Army Air Forces. Each of the 35 sorties is described in detail, with emotional passages on the terror of flak, the loss of close friends, and the trauma of occasional bombs inadvertently dropped on civilians.

William A. McGonigle (1922-2012) from Queens, NY served for 4 years as an Army Air Force lieutenant in the 781st Bombardment Squadron, part of the 465th Bombardment Group. He flew on B-24 liberators out of Pantanella Airfield in Italy, hitting Axis targets throughout southern Europe, with a brief detachment to fly lighter missions on a P-38. He was trained as both a bombardier and navigator, filling either role as needed.

With a few rare exceptions, Lieutenant McGonigle wrote in his diary only on mission days, omitting the tedium of base life. Almost every page describes harrowing air combat. The diary begins just 5 days after D-Day, with the handwriting regressing from tidy to harried as the missions pile up. One of the early passages describes an American ground crew sergeant who had been taking bribes (presumably from the Italian resistance) to sabotage planes: "Some ground crew M/Sgt was caught recently. He'd been sabotaging 24's for a $1000 apiece. Earned $17,000, that was 170 men went down because of him. Imagine a person like that. Probably talked with the crews before they took off, and all the time in the back of his mind was the thought, the knowledge, that they wouldn't come back" (23 June).

A 16 July flight to Vienna was particularly difficult: "Forgot my flak helmet, and when we hit the flak, I just prayed." The plane lagged after losing an engine, so "we salvoed our bomb load, 5 1000#, to catch up just 4 minutes before the target. Just missed a small village, I hope." Similarly, he wrote about a 7 December run to Bratislava, Czechoslovakia: "Unfortunately we hit a small village. Could see the flame of the exploding 500 pounders amongst the little houses. Felt a little sick."

On 19 July, his nose gunner was hit by flak: "I removed his metal and leather flak helmets. Didn't look too bad so I directed Jack around the Venice flak areas before attempting first aid"--a medical intervention which he describes at length.

Perhaps the worst flight was 26 July: "We must have been hit quite often. No. 2 engine was smoking badly, two fuel lines in the bomb bays were cut plus hydraulic lines in the nose--lost most of the fluid. . . . The explosion of the oxygen bottle slight due to the low pressure. Knocked Radzig to the floor from the left waist gun. He stayed there. . . . We were expecting to blow up any minute. . . . Nose gunner came out and donned his chute. I snapped up the navigator's table and stood ready to bail out with a map in one hand, trying to keep track of our position in relation to partisan territory. The bomb bays were full of fumes. . . . We wouldn't have dared firing a gun with all those fumes about had fighters attacked. . . . Managed to make it back to the field with about 1/2 hour's gas aboard. . . . We cleared that ship fast, afraid of an impending explosion. . . . She was a good ship. Brought us home despite her wounds."

The most poignant passage was written on a day off, on 8 August, describing a visit to see the grave of his friend Walter "Wally" Maroldo of Staten Island, buried with 3 crewmates in a small military graveyard in the country near Nettuno, south of Rome. "Bornstein had a Jewish Star of David. I could hardly read Wally's name, almost lost control of myself. This couldn't be Wally, so alive, generous, always doing something. This was a rectangle of cement, cold and wet and unyielding." 8 days later he learned the story of Wally's death, which occurred while landing a wounded ship. Apparently the men shot themselves rather than be burned alive: "When the gas ran out, engines stopped and ship crashed. The men on the flight deck were trapped. The Martin turret must have come down. Fire started; the ship was enveloped in flames. Shots were heard, .45s."

McGonigle's plane made a difficult landing on 28 August: "Coming in for a landing at the base, Foy, 1st pilot, found the elevators to be jammed, practically diving into the runway. He puts his feet up on the instrument panel and hauls back, shouting for the co-pilot to do the same. Between them they just barely managed to save the day."

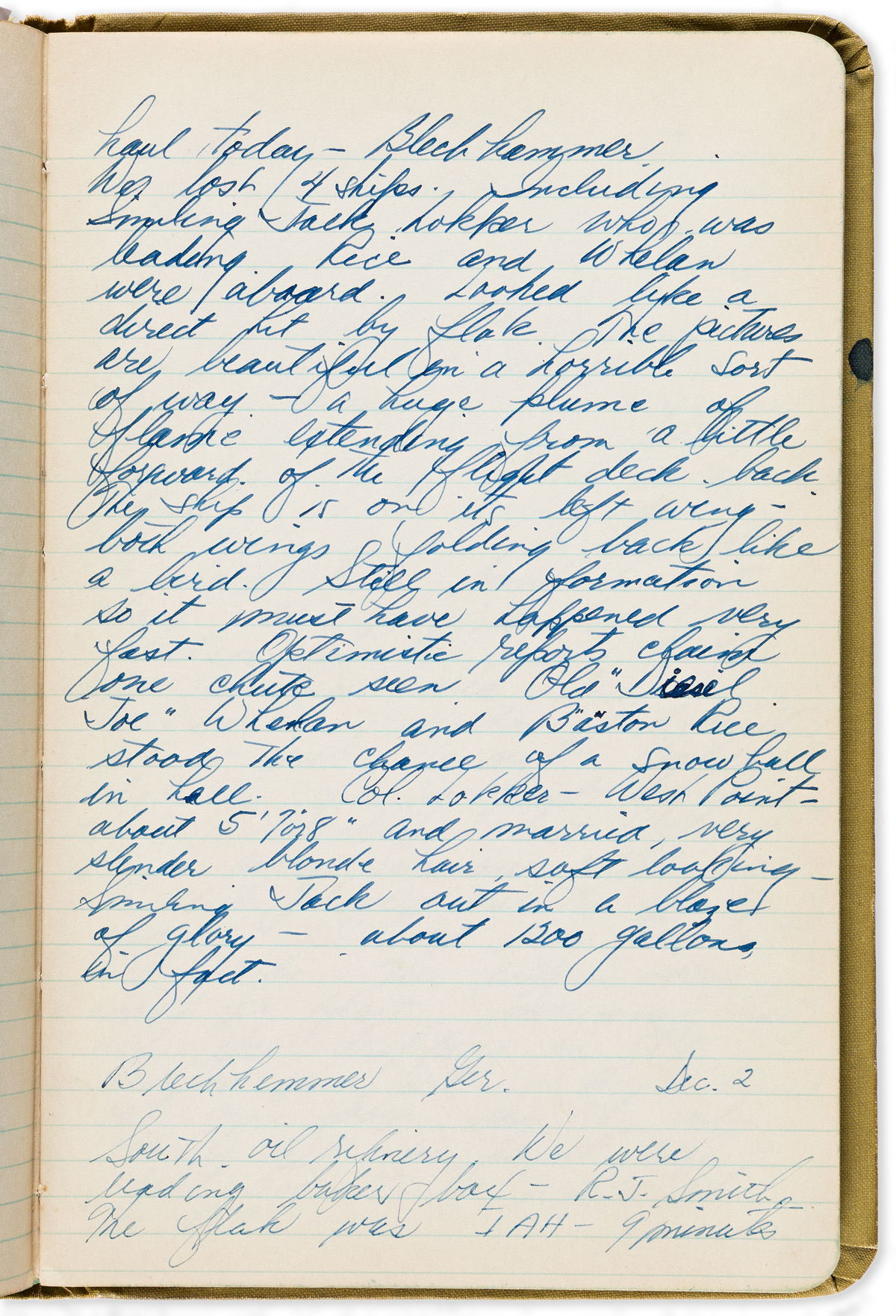

Perhaps the most famed moment of the 465th Bombardment group was the death of its commander, Lt. Col. Clarence John Lokker, captured in an iconic photograph of the burning plane. McGonigle wrote on 20 November: "We lost 4 ships, including Smiling Jack Lokker, who was leading. Rice and Whelan were aboard. Looked like a direct hit by flak. The pictures are beautiful in a horrible sort of way, a huge plume of flame extending from a little forward of the flight deck back. The ship is on its left wing, both wings folding back like a bird. Still in formation, so it must have happened very fast. Optimistic reports claim one chute seen. Old 'Diesel Joe' Whelan and 'Baston' Rice stood the chance of a snowball in hell. Col. Lokker, West Point, about 5'7" or 8" and married, very slender, blonde hair, soft looking. Smiling Jack out in a blaze of glory, about 1200 gallons, in fact."

The diary's final entry was unusually terse, concluding with long-awaited words: "Very snafued deal. Flak was nowhere near us. We hit wrong target . . . probably plowed some farmer's field for him. 35 sorties--finito." In the rear of the volume are a group of poems on the bombers' life, most of them apparently unpublished; two may have been by McGonigle.

Reading through this diary, it seems remarkable that Lieutenant McGonigle--or anyone--survived the requisite 35 missions and returned home to America. He went on to a career as an accountant, and suffered from post-traumatic stress. Often his only consolation was listening to Bach's Musical Offering, which was used as the opening theme on Alan Chapman's radio program for KUSC in California. The consignor's proceeds from this lot will be donated to Chapman's show in his honor.

With--a pair of original 8 x 10 photographs, one of McGonigle in flight gear, and the other of his crew in training in Havana, 1944, annotated with his crewmates' names and fates; a page from his yearbook at Fordham University, where he studied accounting on the G.I. Bill after the war; McGonigle's carbon-copy mission list from February 1945, certifying his 35th sortie ; 3 copies of other service papers; His typescript memoir, "WW2 War Memories," 8 pages, dated 24 March 2007. Additional notes on the diary are available upon request.

William A. McGonigle (1922-2012) from Queens, NY served for 4 years as an Army Air Force lieutenant in the 781st Bombardment Squadron, part of the 465th Bombardment Group. He flew on B-24 liberators out of Pantanella Airfield in Italy, hitting Axis targets throughout southern Europe, with a brief detachment to fly lighter missions on a P-38. He was trained as both a bombardier and navigator, filling either role as needed.

With a few rare exceptions, Lieutenant McGonigle wrote in his diary only on mission days, omitting the tedium of base life. Almost every page describes harrowing air combat. The diary begins just 5 days after D-Day, with the handwriting regressing from tidy to harried as the missions pile up. One of the early passages describes an American ground crew sergeant who had been taking bribes (presumably from the Italian resistance) to sabotage planes: "Some ground crew M/Sgt was caught recently. He'd been sabotaging 24's for a $1000 apiece. Earned $17,000, that was 170 men went down because of him. Imagine a person like that. Probably talked with the crews before they took off, and all the time in the back of his mind was the thought, the knowledge, that they wouldn't come back" (23 June).

A 16 July flight to Vienna was particularly difficult: "Forgot my flak helmet, and when we hit the flak, I just prayed." The plane lagged after losing an engine, so "we salvoed our bomb load, 5 1000#, to catch up just 4 minutes before the target. Just missed a small village, I hope." Similarly, he wrote about a 7 December run to Bratislava, Czechoslovakia: "Unfortunately we hit a small village. Could see the flame of the exploding 500 pounders amongst the little houses. Felt a little sick."

On 19 July, his nose gunner was hit by flak: "I removed his metal and leather flak helmets. Didn't look too bad so I directed Jack around the Venice flak areas before attempting first aid"--a medical intervention which he describes at length.

Perhaps the worst flight was 26 July: "We must have been hit quite often. No. 2 engine was smoking badly, two fuel lines in the bomb bays were cut plus hydraulic lines in the nose--lost most of the fluid. . . . The explosion of the oxygen bottle slight due to the low pressure. Knocked Radzig to the floor from the left waist gun. He stayed there. . . . We were expecting to blow up any minute. . . . Nose gunner came out and donned his chute. I snapped up the navigator's table and stood ready to bail out with a map in one hand, trying to keep track of our position in relation to partisan territory. The bomb bays were full of fumes. . . . We wouldn't have dared firing a gun with all those fumes about had fighters attacked. . . . Managed to make it back to the field with about 1/2 hour's gas aboard. . . . We cleared that ship fast, afraid of an impending explosion. . . . She was a good ship. Brought us home despite her wounds."

The most poignant passage was written on a day off, on 8 August, describing a visit to see the grave of his friend Walter "Wally" Maroldo of Staten Island, buried with 3 crewmates in a small military graveyard in the country near Nettuno, south of Rome. "Bornstein had a Jewish Star of David. I could hardly read Wally's name, almost lost control of myself. This couldn't be Wally, so alive, generous, always doing something. This was a rectangle of cement, cold and wet and unyielding." 8 days later he learned the story of Wally's death, which occurred while landing a wounded ship. Apparently the men shot themselves rather than be burned alive: "When the gas ran out, engines stopped and ship crashed. The men on the flight deck were trapped. The Martin turret must have come down. Fire started; the ship was enveloped in flames. Shots were heard, .45s."

McGonigle's plane made a difficult landing on 28 August: "Coming in for a landing at the base, Foy, 1st pilot, found the elevators to be jammed, practically diving into the runway. He puts his feet up on the instrument panel and hauls back, shouting for the co-pilot to do the same. Between them they just barely managed to save the day."

Perhaps the most famed moment of the 465th Bombardment group was the death of its commander, Lt. Col. Clarence John Lokker, captured in an iconic photograph of the burning plane. McGonigle wrote on 20 November: "We lost 4 ships, including Smiling Jack Lokker, who was leading. Rice and Whelan were aboard. Looked like a direct hit by flak. The pictures are beautiful in a horrible sort of way, a huge plume of flame extending from a little forward of the flight deck back. The ship is on its left wing, both wings folding back like a bird. Still in formation, so it must have happened very fast. Optimistic reports claim one chute seen. Old 'Diesel Joe' Whelan and 'Baston' Rice stood the chance of a snowball in hell. Col. Lokker, West Point, about 5'7" or 8" and married, very slender, blonde hair, soft looking. Smiling Jack out in a blaze of glory, about 1200 gallons, in fact."

The diary's final entry was unusually terse, concluding with long-awaited words: "Very snafued deal. Flak was nowhere near us. We hit wrong target . . . probably plowed some farmer's field for him. 35 sorties--finito." In the rear of the volume are a group of poems on the bombers' life, most of them apparently unpublished; two may have been by McGonigle.

Reading through this diary, it seems remarkable that Lieutenant McGonigle--or anyone--survived the requisite 35 missions and returned home to America. He went on to a career as an accountant, and suffered from post-traumatic stress. Often his only consolation was listening to Bach's Musical Offering, which was used as the opening theme on Alan Chapman's radio program for KUSC in California. The consignor's proceeds from this lot will be donated to Chapman's show in his honor.

With--a pair of original 8 x 10 photographs, one of McGonigle in flight gear, and the other of his crew in training in Havana, 1944, annotated with his crewmates' names and fates; a page from his yearbook at Fordham University, where he studied accounting on the G.I. Bill after the war; McGonigle's carbon-copy mission list from February 1945, certifying his 35th sortie ; 3 copies of other service papers; His typescript memoir, "WW2 War Memories," 8 pages, dated 24 March 2007. Additional notes on the diary are available upon request.

Exhibition Hours

Exhibition Hours

Aliquam vulputate ornare congue. Vestibulum maximus, libero in placerat faucibus, risus nisl molestie massa, ut maximus metus lectus vel lorem.