Sale 2646 - Lot 300

Price Realized: $ 3,000

Price Realized: $ 3,750

?Final Price Realized includes Buyer’s Premium added to Hammer Price

Estimate: $ 5,000 - $ 7,500

(WORLD WAR TWO.) Prison diary, correspondence, and other papers of Daniel MacIntosh, a Bataan Death March survivor. Several hundred items in two boxes (0.8 linear feet), plus two swords; condition generally strong. Various places, 1940-1949

Additional Details

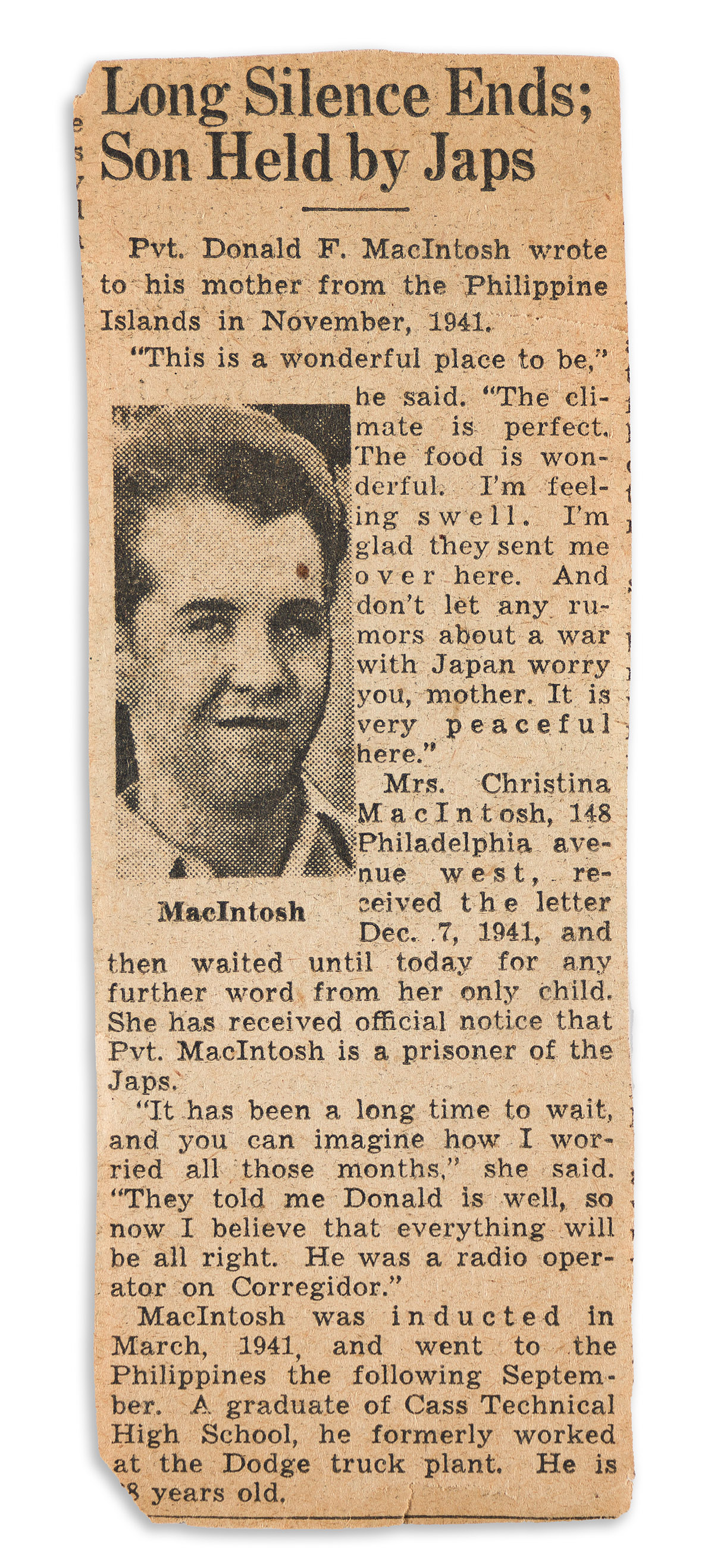

Daniel Fraser MacIntosh (1914-1980) of Detroit was a corporal in the 200th Coast Artillery Regiment when captured by the Japanese at the Battle of Corregidor on 8 April 1942. He survived the Bataan Death March and, according to a news clipping in this collection, he "spent 11 days at the infamous Camp O'Donnell. He was among 10 of 100 soldiers who survived the cruelties imposed while building roads for the enemy." News of his imprisonment did not reach the United States until June 1943, and he did not receive his first letters from home until May 1944. His parents were natives of Nova Scotia, Canada; many of the letters he received were from friends and family in Nova Scotia.

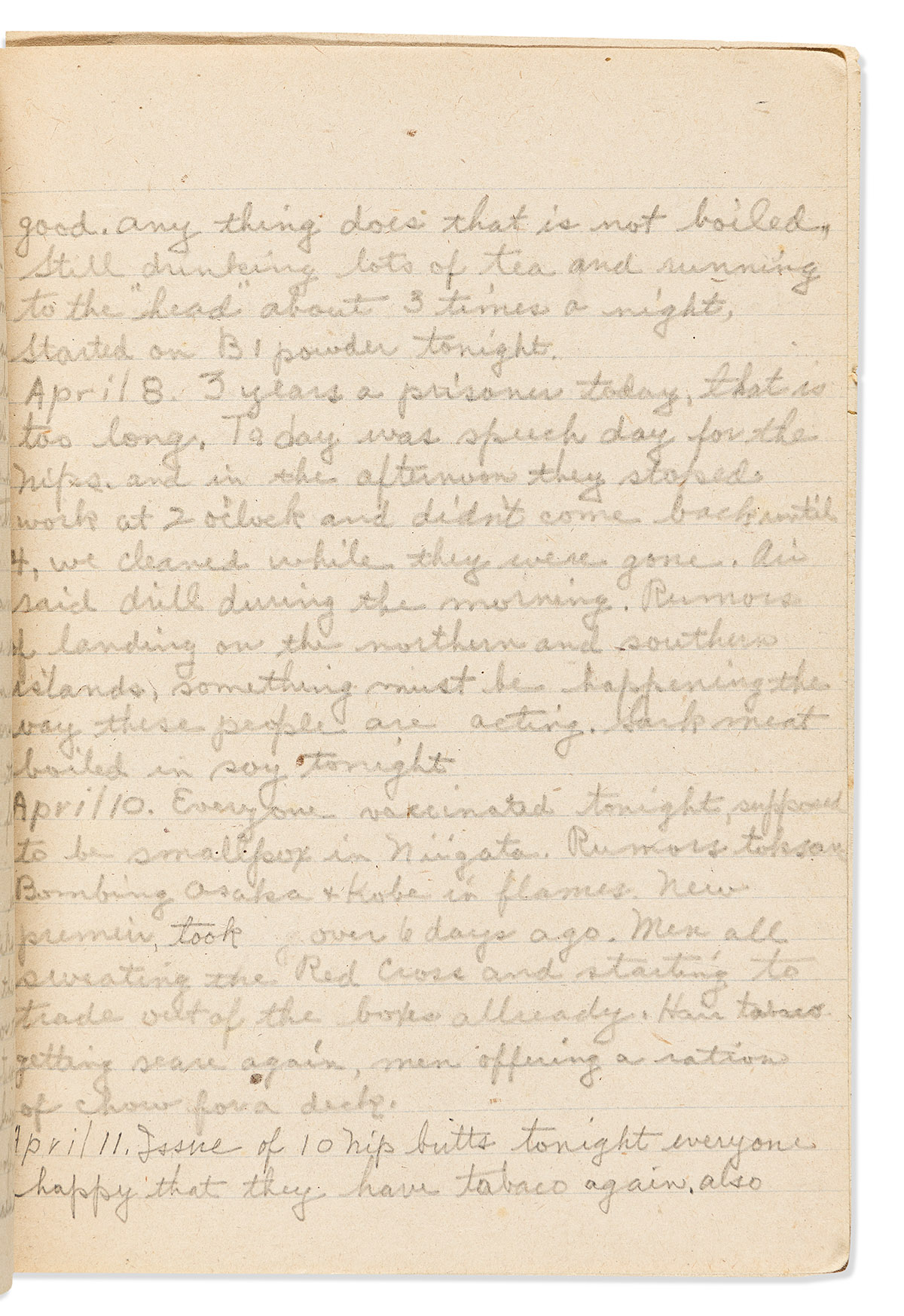

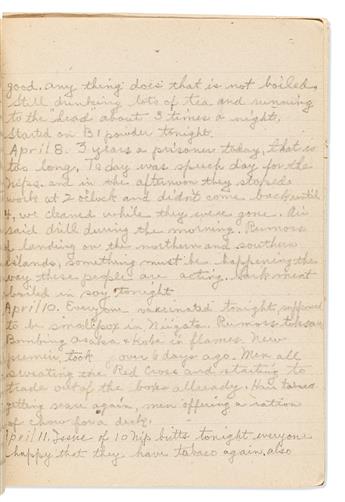

MacIntosh's diary bears his title "The Ramblings and Jottings of a Prisoner of War." It was kept at a prison labor camp in Niigata, Japan, on the western coast north of Tokyo, during the final months of his imprisonment. It includes 46 pages of entries from 1 January to 10 September 1945, telling a story of starvation and abuse tempered with hope that the war might be ending soon. MacIntosh had only occasional contact with the outside world beyond rumors gleaned from his guards. On 12 February, "Received ten letters from mother, some almost a year old." Beatings of the prisoners were almost routine: "Got my ears boxed by Paddle Foot for washing up 10 minutes early, been slightly deaf since!" (30 March). On 7 July, "Vance was caught at Marusso after beans, and the seven men beat him about the head so bad he is in a coma and is now in the hospital."

MacIntosh spent his days working in a hammer mill. His scant rations are often described in careful detail. On 9 May, "We had to carry a bucket of garbage for the pig, and you ought to see these P.O.W.'s dive into it. I got 3 fried fish heads and a handful of bones. This dam pig eats better than we do." On 17 May, "Had something today I never ate in life. Rat, tastes good, something like chicken. 3 of the men caught 17 of them and had a feed." The local civilians seemed to be starving as well: "We hauled 20 bags of barley on sleds from the highway to camp. Some of the barley was on the truck bed when the bags came off. We filled our pockets and when we got into camp, they made us empty it all into a box, then 3 men went back with a broom, shovel and a box and swept up the road. The civilians were picking it up out of the snow" (16 February). Twice the prisoners were treated to boxes from the Red Cross, making themselves ill on the rich food.

While a large percentage of the prisoners had died within the first two years, by 1945 those still remaining were grizzled survivors: "Klutz died last night, first man in over a year, funeral services tonight. . . . Nice funeral service for Klutz. . . . Quite different from last year. Harvey laid in a box in the shit house for 3 days before he was cremated" (29-30 March). The mood began to shift on 22 April: "Well, today I saw my first B-29 flying about 30,000 ft. right overhead." Rumors trickled in about the death of Hitler. After a 20 June air raid, MacIntosh wrote "This is the first Allied action we have seen since April 8, 1942 when Cregadior replied to the Nips' artillery at Cob Cabin Field" in the Philippines. Groups of POW's arrived at the camp from further south. American planes regularly strafed the area and dropped mines in the harbor. The commandant announced that the war was over on 19 August, and two days later: "The pig was killed at 1:30 a.m. by persons unknown. We had the guts at noon, for supper the tastiest stew in a long time." Additional extracts from the diary are available upon request.

The diary is prefaced by 8 pages of memoranda, most notably an epic poem titled "Vindication" which he wrote in response to a 1939 Reader's Digest editorial proclaiming his generation "soft, aimless, and generally immature": "We were soft, and aimless, and weaklings / We lived for ourselves alone / But now we are tempered with fire / And we're ready U.S. to come home." At the rear of the diary are 4 pages of retained copies of letters he sent home, December 1944 to May 1945.

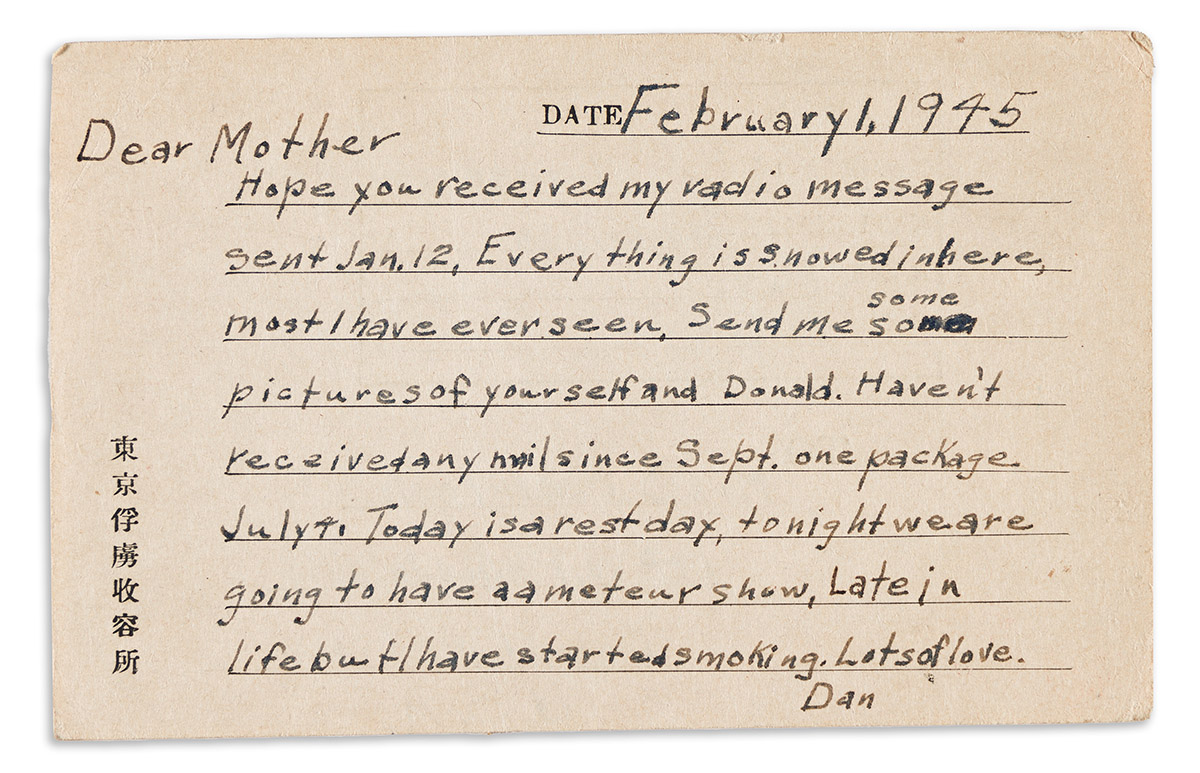

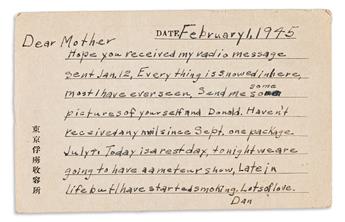

Also included are many letters from the war period. They include one postcard sent from MacIntosh to his mother dated 1 February 1945: "Hope you received my radio message sent Jan. 12. Everything is snowed in here, most I have ever seen. Send me some pictures of yourself and Donald. Haven't received any mail since Sept., one package July 4. Today is a rest day, tonight we are going to have an amateur show. Late in life, but I have started smoking."

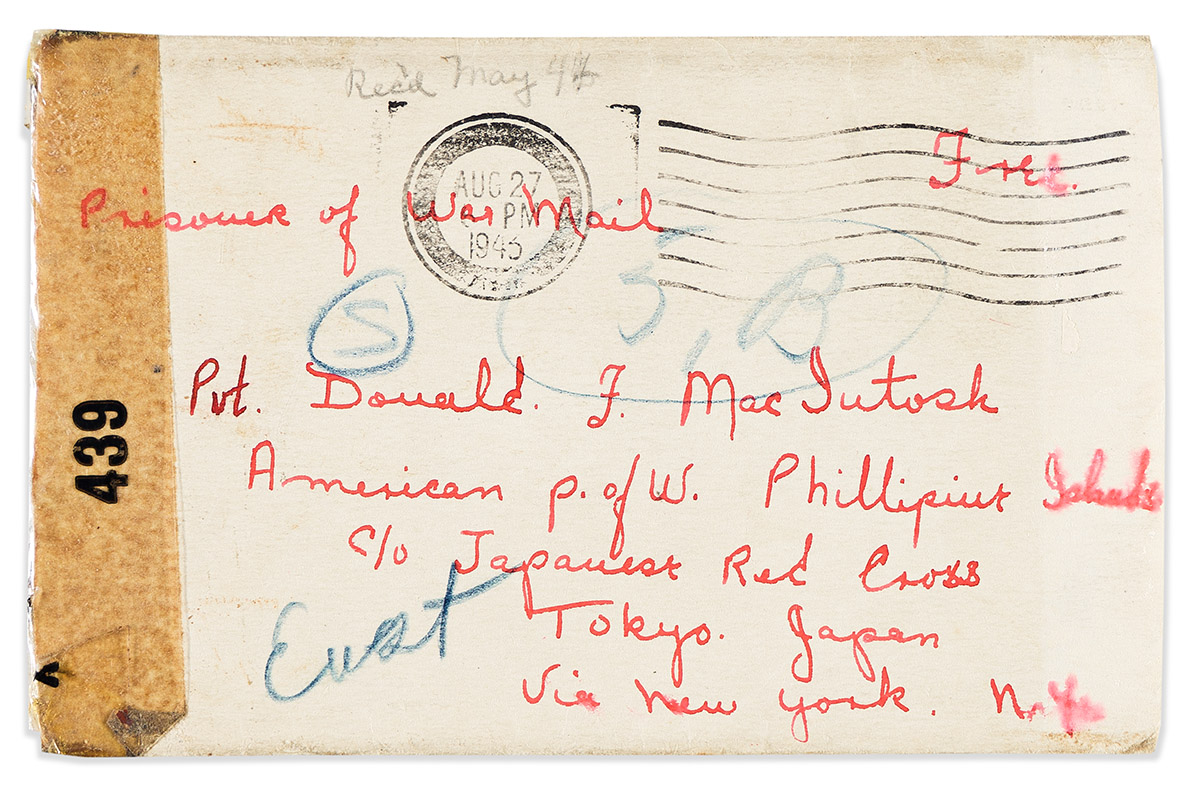

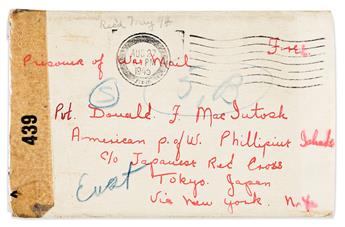

Dozens of letters and postcards addressed to MacIntosh during his imprisonment from friends and family are dated 1943 and 1944, with original postal covers addressed to him care of the Japanese Red Cross, bearing censor tape and noted with the date he actually received them (many about a year after they were sent). Most of these letters are extremely short. A printed slip explains that by order of the Japanese government, letters could not be longer than 25 words, and could not include any military or political content. The letters and telegrams he sent to his mother in September-October 1945 after his release are also included, as well as several letters welcoming him back to the States.

After being released from prison on 5 September 1945, MacIntosh was sent back to the United States for recovery at a military hospital, and separated from the service in April 1946. He returned to Japan for 11 months in 1948 and 1949 to serve as a witness against his captors in war crimes trials. From this period, we have a box of more than 100 snapshots taken in Japan, most of them uncaptioned; and 8 letters written to his mother from August and September 1948. On 19 August he reported visiting the ruins of his old prison camp. On 28 August, after investigations, "we picked out the worst ones & took their names . . . Some of them were certainly scared when they saw us, thought they were safe after all these years. We are going to charge them all with murder and expect to hang a lot of them." Other highlights include:

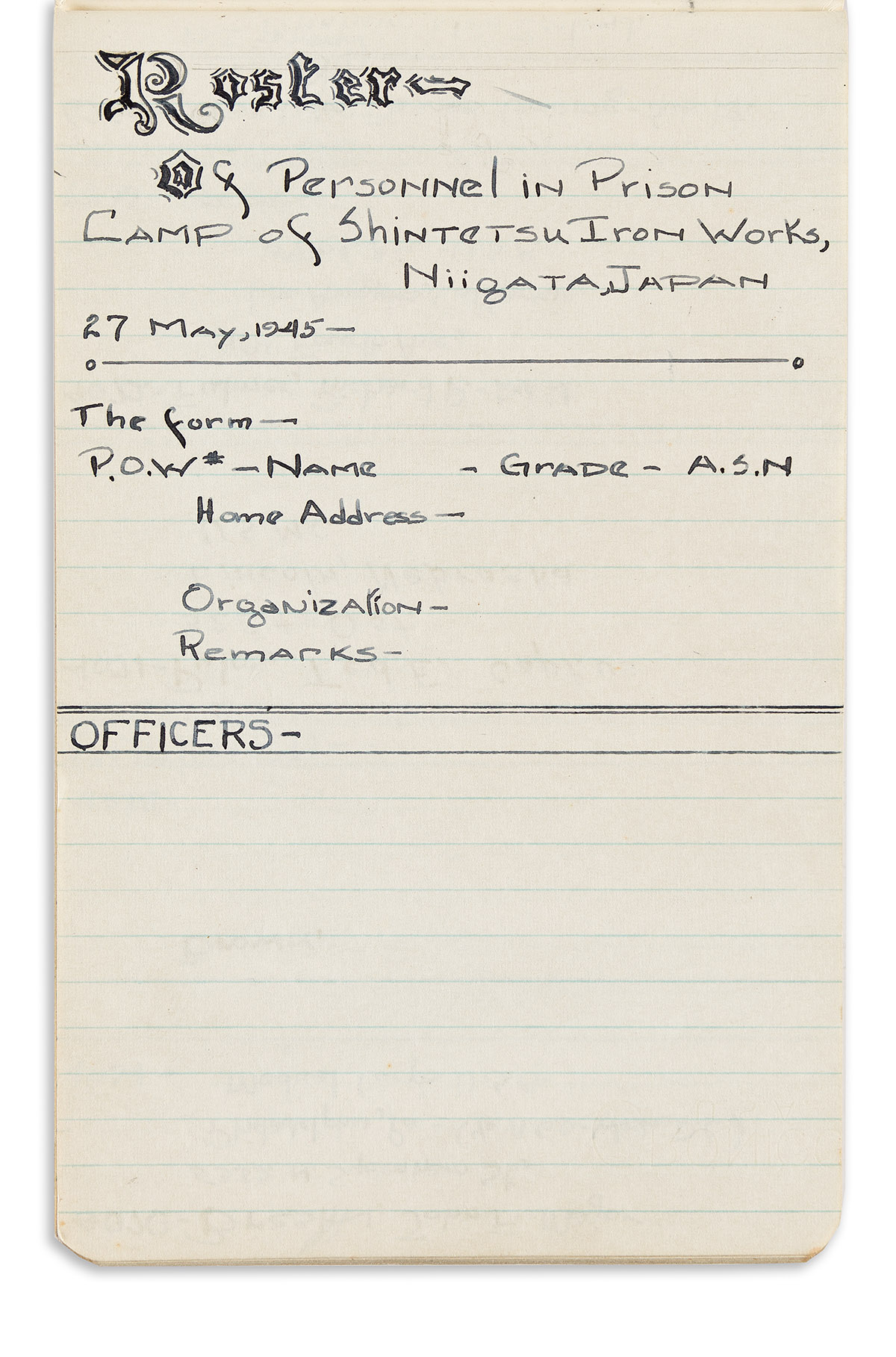

"Roster of Personnel in Prison Camp of Shintetsu Iron Works." Lists dozens of prisoners and their home addresses in a small notebook. Niigata, Japan, 27 May 1945.

A 10 x 13-inch copy print group photograph of the prisoners and their guards, undated.

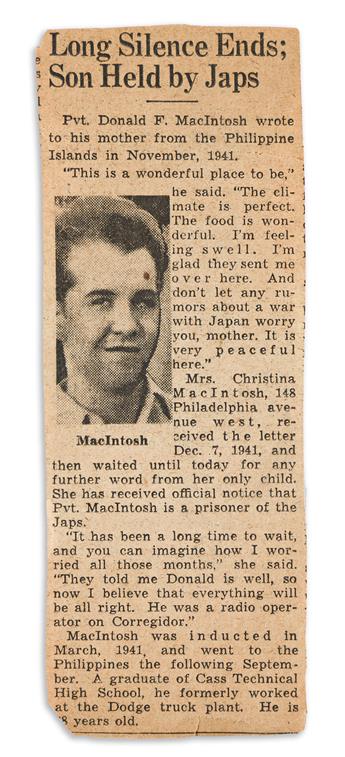

Printed ephemera including several issues of the "Bataan Relief Organization Bulletin" and the Red Cross "Prisoners of War Bulletin" sent to MacIntosh's mother, 1943-1945; several news clippings about MacIntosh's war service and captivity; and a thick folder of printed orders and rosters from his hospitalization and release, 1945-1946.

Approximately 200 letters to fiancé Dolores Schoeppel of Jefferson Barracks, MO, unexamined and still in envelopes, most postmarked Detroit, February 1946 to October 1947. They were married in June 1949, and he later worked as an accountant at a steel plant in Dearborn, MI.

Pair of swords engraved with Japanese characters, each about 26 inches; lacking grips, hardware detached, one lacking crossguard, some rust.

An important and evocative archive documenting life at one of the infamous Japanese prison work camps.

MacIntosh's diary bears his title "The Ramblings and Jottings of a Prisoner of War." It was kept at a prison labor camp in Niigata, Japan, on the western coast north of Tokyo, during the final months of his imprisonment. It includes 46 pages of entries from 1 January to 10 September 1945, telling a story of starvation and abuse tempered with hope that the war might be ending soon. MacIntosh had only occasional contact with the outside world beyond rumors gleaned from his guards. On 12 February, "Received ten letters from mother, some almost a year old." Beatings of the prisoners were almost routine: "Got my ears boxed by Paddle Foot for washing up 10 minutes early, been slightly deaf since!" (30 March). On 7 July, "Vance was caught at Marusso after beans, and the seven men beat him about the head so bad he is in a coma and is now in the hospital."

MacIntosh spent his days working in a hammer mill. His scant rations are often described in careful detail. On 9 May, "We had to carry a bucket of garbage for the pig, and you ought to see these P.O.W.'s dive into it. I got 3 fried fish heads and a handful of bones. This dam pig eats better than we do." On 17 May, "Had something today I never ate in life. Rat, tastes good, something like chicken. 3 of the men caught 17 of them and had a feed." The local civilians seemed to be starving as well: "We hauled 20 bags of barley on sleds from the highway to camp. Some of the barley was on the truck bed when the bags came off. We filled our pockets and when we got into camp, they made us empty it all into a box, then 3 men went back with a broom, shovel and a box and swept up the road. The civilians were picking it up out of the snow" (16 February). Twice the prisoners were treated to boxes from the Red Cross, making themselves ill on the rich food.

While a large percentage of the prisoners had died within the first two years, by 1945 those still remaining were grizzled survivors: "Klutz died last night, first man in over a year, funeral services tonight. . . . Nice funeral service for Klutz. . . . Quite different from last year. Harvey laid in a box in the shit house for 3 days before he was cremated" (29-30 March). The mood began to shift on 22 April: "Well, today I saw my first B-29 flying about 30,000 ft. right overhead." Rumors trickled in about the death of Hitler. After a 20 June air raid, MacIntosh wrote "This is the first Allied action we have seen since April 8, 1942 when Cregadior replied to the Nips' artillery at Cob Cabin Field" in the Philippines. Groups of POW's arrived at the camp from further south. American planes regularly strafed the area and dropped mines in the harbor. The commandant announced that the war was over on 19 August, and two days later: "The pig was killed at 1:30 a.m. by persons unknown. We had the guts at noon, for supper the tastiest stew in a long time." Additional extracts from the diary are available upon request.

The diary is prefaced by 8 pages of memoranda, most notably an epic poem titled "Vindication" which he wrote in response to a 1939 Reader's Digest editorial proclaiming his generation "soft, aimless, and generally immature": "We were soft, and aimless, and weaklings / We lived for ourselves alone / But now we are tempered with fire / And we're ready U.S. to come home." At the rear of the diary are 4 pages of retained copies of letters he sent home, December 1944 to May 1945.

Also included are many letters from the war period. They include one postcard sent from MacIntosh to his mother dated 1 February 1945: "Hope you received my radio message sent Jan. 12. Everything is snowed in here, most I have ever seen. Send me some pictures of yourself and Donald. Haven't received any mail since Sept., one package July 4. Today is a rest day, tonight we are going to have an amateur show. Late in life, but I have started smoking."

Dozens of letters and postcards addressed to MacIntosh during his imprisonment from friends and family are dated 1943 and 1944, with original postal covers addressed to him care of the Japanese Red Cross, bearing censor tape and noted with the date he actually received them (many about a year after they were sent). Most of these letters are extremely short. A printed slip explains that by order of the Japanese government, letters could not be longer than 25 words, and could not include any military or political content. The letters and telegrams he sent to his mother in September-October 1945 after his release are also included, as well as several letters welcoming him back to the States.

After being released from prison on 5 September 1945, MacIntosh was sent back to the United States for recovery at a military hospital, and separated from the service in April 1946. He returned to Japan for 11 months in 1948 and 1949 to serve as a witness against his captors in war crimes trials. From this period, we have a box of more than 100 snapshots taken in Japan, most of them uncaptioned; and 8 letters written to his mother from August and September 1948. On 19 August he reported visiting the ruins of his old prison camp. On 28 August, after investigations, "we picked out the worst ones & took their names . . . Some of them were certainly scared when they saw us, thought they were safe after all these years. We are going to charge them all with murder and expect to hang a lot of them." Other highlights include:

"Roster of Personnel in Prison Camp of Shintetsu Iron Works." Lists dozens of prisoners and their home addresses in a small notebook. Niigata, Japan, 27 May 1945.

A 10 x 13-inch copy print group photograph of the prisoners and their guards, undated.

Printed ephemera including several issues of the "Bataan Relief Organization Bulletin" and the Red Cross "Prisoners of War Bulletin" sent to MacIntosh's mother, 1943-1945; several news clippings about MacIntosh's war service and captivity; and a thick folder of printed orders and rosters from his hospitalization and release, 1945-1946.

Approximately 200 letters to fiancé Dolores Schoeppel of Jefferson Barracks, MO, unexamined and still in envelopes, most postmarked Detroit, February 1946 to October 1947. They were married in June 1949, and he later worked as an accountant at a steel plant in Dearborn, MI.

Pair of swords engraved with Japanese characters, each about 26 inches; lacking grips, hardware detached, one lacking crossguard, some rust.

An important and evocative archive documenting life at one of the infamous Japanese prison work camps.

Exhibition Hours

Exhibition Hours

Aliquam vulputate ornare congue. Vestibulum maximus, libero in placerat faucibus, risus nisl molestie massa, ut maximus metus lectus vel lorem.