Sale 2533 - Lot 269

Price Realized: $ 2,600

Price Realized: $ 3,250

?Final Price Realized includes Buyer’s Premium added to Hammer Price

Estimate: $ 1,200 - $ 1,800

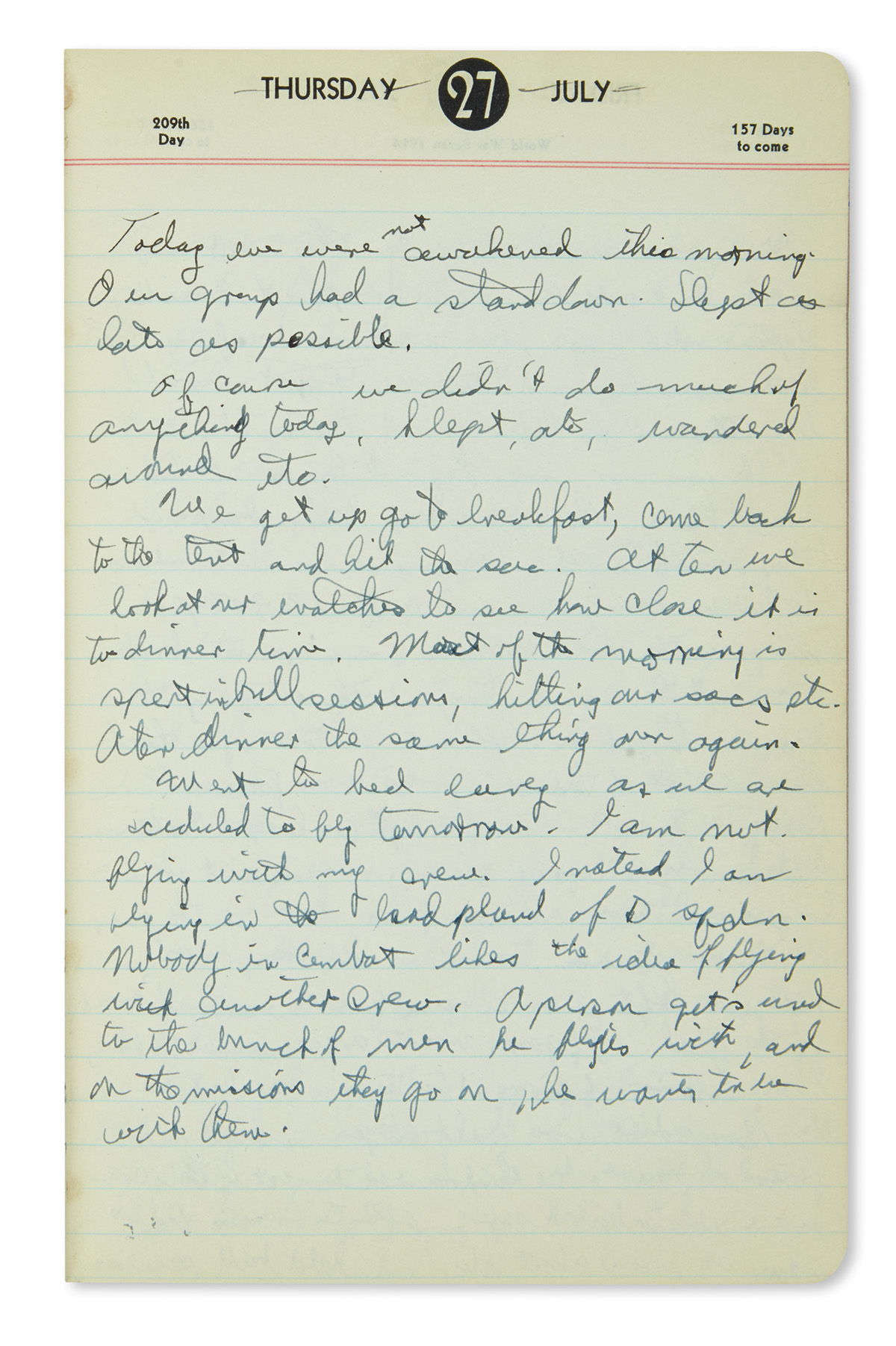

'IN MY MIND I CAN HEAR THE SCREAMS OF THE MEN' (WORLD WAR TWO.) Thomas, Richard E. Diary of a bomber navigator on 39 combat missions in Italy. 215 manuscript diary pages (29 of them blank, none of them blank on active duty in Italy) plus [8] pages of memoranda. 8vo, original limp calf, minor wear; minimal wear to contents except for blood stains on the 21 and 22 May entries, marked 'Nose bleed'; 3 photographs and envelope from a friend and 1986 provenance note laid in; father's name and address on title page. Vp, 1 January to 2 August 1944

Additional Details

A dramatic diary of a B-24 navigator trying to get through his appointed 50 missions safely, a narrative reminiscent in many ways of Joseph Heller's novel Catch-22, although his spare, gritty style suggests a fondness for Hemingway.

Richard Edward Thomas (1922-1944) was born and raised in Massachusetts, the son of Syrian immigrant parents. In 1930, the family lived in Medford near Boston, and by 1944 they had moved to Springfield in the western part of the state. His father was an investigator with the treasury department. He enlisted into the United States Army Air Force in August 1942 and spent more than a year in flight training. He trained as a navigator and was assigned as a second lieutenant to the 782nd Bombardment Squadron, 465th Bombardment Group. As this diary begins, he was just finishing his training. Describing his first leave from McCook Air Field in Nebraska, he wrote 'I spent it getting drunk in Denver with a woman, a married woman with a child. . . . When I was a civilian and in college I was never bothered by women. They didn't mean a piss hole in the snow to me. I intended to become a surgeon. . . . Now it's changed, I'm in the army. I must live for the moment' (3-4 January). His flight group began a circuitous route to the Mediterranean theater in February 1944; Thomas offers vivid descriptions of Belém and Natal, Brazil (21-26 February), Dakar, Senegal (28 February to 3 March), Marrakesh, Morocco (3-5 March) and Tunis (8 March to 15 April).

The group arrived at Pantanella Airfield in Italy on 20 April, and soon began combat operations with the 55th Fighter Wing, 15th Air Force, flying in Consolidated B-24 Liberators. The first mission was on 5 May, a German army base at Podgorica in Yugoslavia: 'Our bombs made a very good pattern as was shown in pictures taken off the raid. It was completely destroyed. Coming off the target, the lead sqdn ran into clouds and became separated. Therefore we led the rest of the groups home. I was lead navigator, did a good job in taking us home.' The next day was a six-hour mission to Romania: 'We did see enemy flak, and fighters. . . . I had a wrong type of parachute issued, I did not know it until we had landed. If anything had happened, I would have been shit out of luck.' Before his third mission, he already sounded jaded: 'The faster I get my 50 in, the better. I'm sick of this shit' (8 May). A 14 May raid was undermined by an indecisive major who asked Thomas's advice and then failed to follow it: 'The group leaders, big and important majors, blown up by their supposed importance, fuck us up every time.' 22 May brought 'heavy concentrated flak, the pilot's windshield was blown out, and we also received a flat tire. We didn't know this until we were landing.' After less than a month of combat, Thomas reported 'Most of us now are flak happy. At first it didn't bother us because we only saw the light stuff. But now that we've moved up to the big leagues, and we've been through this stuff on several occasions, we've all become flak happy' (31 May).

On D-Day, Thomas wrote 'Today the invasion started. From now on our targets will be more difficult, maybe farther from our home base' (6 June). On a 16 June mission to Vienna, he wrote 'We were intercepted by enemy fighters. I saw two blow up there, and couple over the target. That's the most horrible thing I can think of now, a burning plane. In my mind I can hear the screams of the men.' On a 23 June mission to Guirgui, Romania (his 23rd mission), 'Flak was moderate and heavy and accurate. Our bombardier as a result of today's mission will receive the Purple Heart. He was slightly wounded today.' A seven-day leave was spent in Rome and Naples, 16-22 July. On a 28 July raid to the Polesti oil refinery, 'We lost one plane. The bombardier was Walt Hogan, a high school friend of mine. We think he and the rest of his crew were able to bail out safely.'

On 2 August, Thomas's plane hit the docks at Genoa: 'Same old story, flak, long mission, weather and fighters, but I have 12 to go.' He returned safely to the base, took a shower, ate fried chicken, and 'tried to deduce the whereabouts of tomorrow's mission. . . . Tomorrow I fly.' The diary ends with these words.

The next day was Lieutenant Thomas's 39th mission, to the southern German city of Friedrichshafen. 17 Allied planes were lost that day, including his. A 1986 note in the diary explained that 'a low altitude flight blew up the oil refinery but also destroyed the planes.' The 465th Bombardment Group received a Distinguished Unit Citation for its role in the attack.

Richard Edward Thomas (1922-1944) was born and raised in Massachusetts, the son of Syrian immigrant parents. In 1930, the family lived in Medford near Boston, and by 1944 they had moved to Springfield in the western part of the state. His father was an investigator with the treasury department. He enlisted into the United States Army Air Force in August 1942 and spent more than a year in flight training. He trained as a navigator and was assigned as a second lieutenant to the 782nd Bombardment Squadron, 465th Bombardment Group. As this diary begins, he was just finishing his training. Describing his first leave from McCook Air Field in Nebraska, he wrote 'I spent it getting drunk in Denver with a woman, a married woman with a child. . . . When I was a civilian and in college I was never bothered by women. They didn't mean a piss hole in the snow to me. I intended to become a surgeon. . . . Now it's changed, I'm in the army. I must live for the moment' (3-4 January). His flight group began a circuitous route to the Mediterranean theater in February 1944; Thomas offers vivid descriptions of Belém and Natal, Brazil (21-26 February), Dakar, Senegal (28 February to 3 March), Marrakesh, Morocco (3-5 March) and Tunis (8 March to 15 April).

The group arrived at Pantanella Airfield in Italy on 20 April, and soon began combat operations with the 55th Fighter Wing, 15th Air Force, flying in Consolidated B-24 Liberators. The first mission was on 5 May, a German army base at Podgorica in Yugoslavia: 'Our bombs made a very good pattern as was shown in pictures taken off the raid. It was completely destroyed. Coming off the target, the lead sqdn ran into clouds and became separated. Therefore we led the rest of the groups home. I was lead navigator, did a good job in taking us home.' The next day was a six-hour mission to Romania: 'We did see enemy flak, and fighters. . . . I had a wrong type of parachute issued, I did not know it until we had landed. If anything had happened, I would have been shit out of luck.' Before his third mission, he already sounded jaded: 'The faster I get my 50 in, the better. I'm sick of this shit' (8 May). A 14 May raid was undermined by an indecisive major who asked Thomas's advice and then failed to follow it: 'The group leaders, big and important majors, blown up by their supposed importance, fuck us up every time.' 22 May brought 'heavy concentrated flak, the pilot's windshield was blown out, and we also received a flat tire. We didn't know this until we were landing.' After less than a month of combat, Thomas reported 'Most of us now are flak happy. At first it didn't bother us because we only saw the light stuff. But now that we've moved up to the big leagues, and we've been through this stuff on several occasions, we've all become flak happy' (31 May).

On D-Day, Thomas wrote 'Today the invasion started. From now on our targets will be more difficult, maybe farther from our home base' (6 June). On a 16 June mission to Vienna, he wrote 'We were intercepted by enemy fighters. I saw two blow up there, and couple over the target. That's the most horrible thing I can think of now, a burning plane. In my mind I can hear the screams of the men.' On a 23 June mission to Guirgui, Romania (his 23rd mission), 'Flak was moderate and heavy and accurate. Our bombardier as a result of today's mission will receive the Purple Heart. He was slightly wounded today.' A seven-day leave was spent in Rome and Naples, 16-22 July. On a 28 July raid to the Polesti oil refinery, 'We lost one plane. The bombardier was Walt Hogan, a high school friend of mine. We think he and the rest of his crew were able to bail out safely.'

On 2 August, Thomas's plane hit the docks at Genoa: 'Same old story, flak, long mission, weather and fighters, but I have 12 to go.' He returned safely to the base, took a shower, ate fried chicken, and 'tried to deduce the whereabouts of tomorrow's mission. . . . Tomorrow I fly.' The diary ends with these words.

The next day was Lieutenant Thomas's 39th mission, to the southern German city of Friedrichshafen. 17 Allied planes were lost that day, including his. A 1986 note in the diary explained that 'a low altitude flight blew up the oil refinery but also destroyed the planes.' The 465th Bombardment Group received a Distinguished Unit Citation for its role in the attack.

Exhibition Hours

Exhibition Hours

Aliquam vulputate ornare congue. Vestibulum maximus, libero in placerat faucibus, risus nisl molestie massa, ut maximus metus lectus vel lorem.