Sale 2646 - Lot 97

Unsold

Estimate: $ 10,000 - $ 15,000

(CIVIL WAR--CONFEDERATE.) Post-Appomattox correspondence of Philip Roddey, the last Confederate general to surrender in the east. 18 manuscript items signed by various parties; generally minor wear. With typed transcripts of most items. In buckram folding case gilt-stamped "Gen. Philip D. Roddey, C.S.A." on spine. Various places, April and May 1865

Additional Details

"We have been forced to succumb. We have no force to offer resistance with. . . . It is almost useless to talk of further resistance."

Brigadier General Philip Dale Roddey (1826-1897) commanded the last substantial Confederate Army unit to surrender in the east. He commanded a cavalry brigade under Nathan Bedford Forrest at the Battle of Selma on 2 April, in which most of their Department of Alabama, Mississippi, and East Louisiana was captured or killed. Much further north, Robert E. Lee's army surrendered at Appomattox on 9 April, and General Johnston surrendered the Army of Tennessee on 26 April. General Taylor surrendered the main remaining body of the Department of Alabama, Mississippi, and East Louisiana on 4 May. Roddey's commander General Forrest surrendered on 9 May, and President Jefferson Davis was captured the following day. Roddey held out for another week after that, surrendering on 17 May. Offered here are Roddey's papers from his final weeks of Confederate service.

The first document is a special order issued to Roddey four days after his forces were scattered in the Selma defeat, signed by Major John Rawle by order of Brigadier General Daniel Weisiger Adams: "Roddey is hereby directed to proceed to such point in District Ala as he may select and organize his command. . . . He is also directed to collect all straggling detachments or soldiers of any command, and forward them to their commands which may be found in his vicinity." Montgomery, AL, 6 April 1865.

Three days later, Rawle wrote directly to Roddey: "The enemy have destroyed the bridge across the river at Centreville. . . . Concentrate your command on the east side of the railroad say about Mapleville. . . . Send a reliable scout towards Centreville to ascertain definitely if it is true that the enemy has destroyed the bridge." Montgomery, AL, 9 April 1865.

The next day, an order came from the aide to Lieutenant General Richard Taylor, ordering Roddey to "collect your command at Greensboro, Ala." and "remount your command from the horses & mules belonging to Tories in North Alabama, driving them (the Tories) out of the country." Marion Junction, AL, 10 April 1865.

One of Roddey's lieutenant colonels (I.S. McCressy?) regretted his inability to counter Union movements: "There are no troops to send on a scout. I probably can send one tomorrow. . . . There is no [telegraph] operator here. If you can send Powers with an apparatus, it would be a great help. . . . There is no forage to be had in this neighborhood or around Elyton. The Yankees, like the locusts in Egypt, literally devoured everything, leaving many families without bread." Montevallo, AL, 17 April 1865.

Roddey had contact with his Union counterpart the next week. Brigadier General Robert S. Granger in a Letter Signed explained that paroled troops would be allowed to return home if "they abstain from all political discussions." Huntsville, AL, 24 April 1865.

A letter from Union General Granger is addressed to Colonel Josiah Patterson of the 5th Alabama Cavalry, one of Roddey's Confederate regiments: "Though not authorized to suspend hostilities . . . I will nevertheless cheerfully concur in your proposition so far as to suspend operations or incoursions south of the Tenn. River. . . . I have no doubt but the war is virtually closed; the surrender of Gen'l Lee & his army, of which there is not a shadow of a doubt, has left your cause without an army on which you can hang a hope of ultimate success. You have fought nobly, and done all that is necessary to sustain the honor of a brave people. To continue this struggle longer . . . would exhibit you to the world as wanting moral courage." Huntsville, AL, 28 April 1865.

The same day, with one of his regimental officers already negotiating for a cease-fire, Roddey reported to his commander General Taylor, ready for continued fighting: "My command which was, as you are awair, somewhat scattered after the fall of Selma, is now being collected, & I have already a considerable number of men in camp. The greater portion of these however, are without arms, accoutrements, horses, & some are in want of clothing. . . . The greatest difficulty . . . is in the matter of procuring horses. . . . One thousand bales of cotton now remaining at exposed points, and likely, if not destroyed, to fall into the hands of the enemy would, if placed at my disposal enable me in a short time to remount my entire command." Greensboro, AL, 28 April 1865. This long missive is docketed three days later on verso with a denial of his request by command of Taylor: "There is no authority vested in departmental com'ds to make such use of gov't cotton."

Roddey still remained in his command a week later when Captain Thomas Crowder, an aide to Confederate General Abraham Buford, urged him to surrender: "The Department has been surrendered. Our armies in the East have surrendered. . . . The General would urge on you to bring forward all your men, in order that they may be paroled. . . . Those who fail to come forward will be considered as outlaws, and will be hunted down by detachments of Federal cavalry. . . . We have been forced to succumb. We have no force to offer resistance with. . . . It is almost useless to talk of further resistance. A guerilla warfare only makes each one engaged therein an outlaw and an outcast, and will end in their destruction." Gainesville, AL, 7 May 1865.

The next day another aide, J.T. Parrish, was still trying to convince Roddey to surrender: "I do not see any hope . . . to get out of a surrender, & however humiliating it may be, let us accept the bitter draught. . . . Let the blame rest upon the cowardly traitorous, many living traitors who have sold their country . . . who has seen the widows, wives & children of the soldier in the field starving for bread, & fed them not, let them rest if they can imbedded in their infamy. A just God will punish, and the patriot will despise them while living & spit upon their graves when dead. . . . I look upon you as having no equal in feeling, in patriotism, in self-sacrificing devotion to your country." Tuscaloosa, AL, 8 May 1865.

Two days later, an aide to General Taylor wrote to General Forrest, appointing Roddey as a commissioner "for the purpose of paroling at Decatur the troops of Brig'd Gen'l Roddey's command." Meridian, MS, 10 May 1865.

Five days later, with virtually every other Confederate general east of the Mississippi already surrendered, Union Captain James P. Metcalf sent Roddey an offer for "the surrender of your command on the terms given Gen'l Lee by Gen'l Grant, and to Gen'l Taylor by Gen'l Canby," Tuscumbia, AL, 15 May 1865.

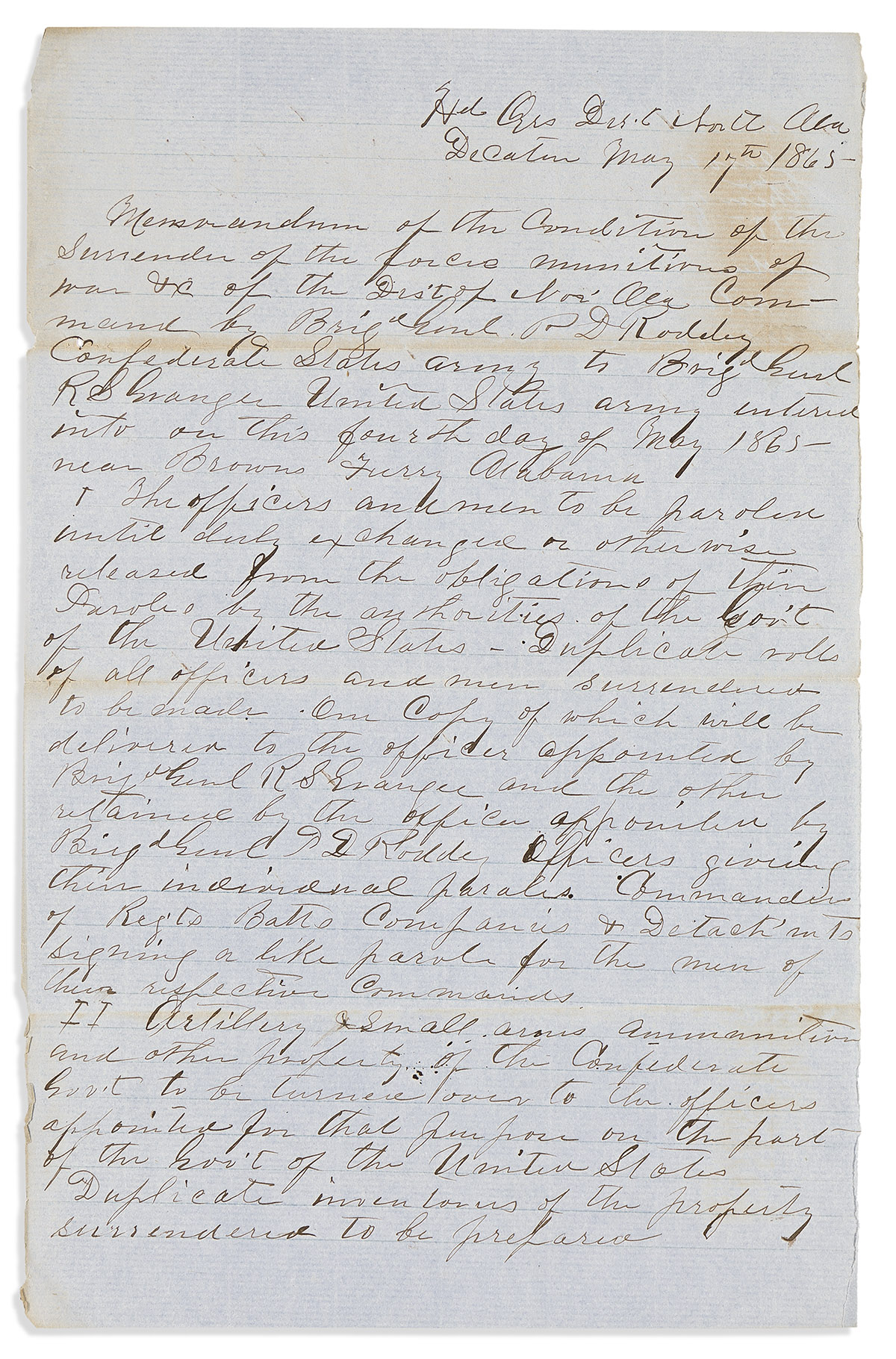

Finally we have a hastily written secretarial copy of the "Memorandum of the Condition of the Surrender of the Forces, Munitions of War &c of the Dist of Nor. Ala. command by Brig'd Gen'l P.D. Roddey." Decatur, AL, 17 May 1865. Two transcripts of the terms of surrender are also included.

After Roddey's surrender, only Texas and Oklahoma (and the CSS Shenandoah) remained under Confederate control.

Brigadier General Philip Dale Roddey (1826-1897) commanded the last substantial Confederate Army unit to surrender in the east. He commanded a cavalry brigade under Nathan Bedford Forrest at the Battle of Selma on 2 April, in which most of their Department of Alabama, Mississippi, and East Louisiana was captured or killed. Much further north, Robert E. Lee's army surrendered at Appomattox on 9 April, and General Johnston surrendered the Army of Tennessee on 26 April. General Taylor surrendered the main remaining body of the Department of Alabama, Mississippi, and East Louisiana on 4 May. Roddey's commander General Forrest surrendered on 9 May, and President Jefferson Davis was captured the following day. Roddey held out for another week after that, surrendering on 17 May. Offered here are Roddey's papers from his final weeks of Confederate service.

The first document is a special order issued to Roddey four days after his forces were scattered in the Selma defeat, signed by Major John Rawle by order of Brigadier General Daniel Weisiger Adams: "Roddey is hereby directed to proceed to such point in District Ala as he may select and organize his command. . . . He is also directed to collect all straggling detachments or soldiers of any command, and forward them to their commands which may be found in his vicinity." Montgomery, AL, 6 April 1865.

Three days later, Rawle wrote directly to Roddey: "The enemy have destroyed the bridge across the river at Centreville. . . . Concentrate your command on the east side of the railroad say about Mapleville. . . . Send a reliable scout towards Centreville to ascertain definitely if it is true that the enemy has destroyed the bridge." Montgomery, AL, 9 April 1865.

The next day, an order came from the aide to Lieutenant General Richard Taylor, ordering Roddey to "collect your command at Greensboro, Ala." and "remount your command from the horses & mules belonging to Tories in North Alabama, driving them (the Tories) out of the country." Marion Junction, AL, 10 April 1865.

One of Roddey's lieutenant colonels (I.S. McCressy?) regretted his inability to counter Union movements: "There are no troops to send on a scout. I probably can send one tomorrow. . . . There is no [telegraph] operator here. If you can send Powers with an apparatus, it would be a great help. . . . There is no forage to be had in this neighborhood or around Elyton. The Yankees, like the locusts in Egypt, literally devoured everything, leaving many families without bread." Montevallo, AL, 17 April 1865.

Roddey had contact with his Union counterpart the next week. Brigadier General Robert S. Granger in a Letter Signed explained that paroled troops would be allowed to return home if "they abstain from all political discussions." Huntsville, AL, 24 April 1865.

A letter from Union General Granger is addressed to Colonel Josiah Patterson of the 5th Alabama Cavalry, one of Roddey's Confederate regiments: "Though not authorized to suspend hostilities . . . I will nevertheless cheerfully concur in your proposition so far as to suspend operations or incoursions south of the Tenn. River. . . . I have no doubt but the war is virtually closed; the surrender of Gen'l Lee & his army, of which there is not a shadow of a doubt, has left your cause without an army on which you can hang a hope of ultimate success. You have fought nobly, and done all that is necessary to sustain the honor of a brave people. To continue this struggle longer . . . would exhibit you to the world as wanting moral courage." Huntsville, AL, 28 April 1865.

The same day, with one of his regimental officers already negotiating for a cease-fire, Roddey reported to his commander General Taylor, ready for continued fighting: "My command which was, as you are awair, somewhat scattered after the fall of Selma, is now being collected, & I have already a considerable number of men in camp. The greater portion of these however, are without arms, accoutrements, horses, & some are in want of clothing. . . . The greatest difficulty . . . is in the matter of procuring horses. . . . One thousand bales of cotton now remaining at exposed points, and likely, if not destroyed, to fall into the hands of the enemy would, if placed at my disposal enable me in a short time to remount my entire command." Greensboro, AL, 28 April 1865. This long missive is docketed three days later on verso with a denial of his request by command of Taylor: "There is no authority vested in departmental com'ds to make such use of gov't cotton."

Roddey still remained in his command a week later when Captain Thomas Crowder, an aide to Confederate General Abraham Buford, urged him to surrender: "The Department has been surrendered. Our armies in the East have surrendered. . . . The General would urge on you to bring forward all your men, in order that they may be paroled. . . . Those who fail to come forward will be considered as outlaws, and will be hunted down by detachments of Federal cavalry. . . . We have been forced to succumb. We have no force to offer resistance with. . . . It is almost useless to talk of further resistance. A guerilla warfare only makes each one engaged therein an outlaw and an outcast, and will end in their destruction." Gainesville, AL, 7 May 1865.

The next day another aide, J.T. Parrish, was still trying to convince Roddey to surrender: "I do not see any hope . . . to get out of a surrender, & however humiliating it may be, let us accept the bitter draught. . . . Let the blame rest upon the cowardly traitorous, many living traitors who have sold their country . . . who has seen the widows, wives & children of the soldier in the field starving for bread, & fed them not, let them rest if they can imbedded in their infamy. A just God will punish, and the patriot will despise them while living & spit upon their graves when dead. . . . I look upon you as having no equal in feeling, in patriotism, in self-sacrificing devotion to your country." Tuscaloosa, AL, 8 May 1865.

Two days later, an aide to General Taylor wrote to General Forrest, appointing Roddey as a commissioner "for the purpose of paroling at Decatur the troops of Brig'd Gen'l Roddey's command." Meridian, MS, 10 May 1865.

Five days later, with virtually every other Confederate general east of the Mississippi already surrendered, Union Captain James P. Metcalf sent Roddey an offer for "the surrender of your command on the terms given Gen'l Lee by Gen'l Grant, and to Gen'l Taylor by Gen'l Canby," Tuscumbia, AL, 15 May 1865.

Finally we have a hastily written secretarial copy of the "Memorandum of the Condition of the Surrender of the Forces, Munitions of War &c of the Dist of Nor. Ala. command by Brig'd Gen'l P.D. Roddey." Decatur, AL, 17 May 1865. Two transcripts of the terms of surrender are also included.

After Roddey's surrender, only Texas and Oklahoma (and the CSS Shenandoah) remained under Confederate control.

Exhibition Hours

Exhibition Hours

Aliquam vulputate ornare congue. Vestibulum maximus, libero in placerat faucibus, risus nisl molestie massa, ut maximus metus lectus vel lorem.