Sale 2437 - Lot 230

Price Realized: $ 120,000

Price Realized: $ 149,000

?Final Price Realized includes Buyer’s Premium added to Hammer Price

Estimate: $ 50,000 - $ 80,000

EDWARD HOPPER

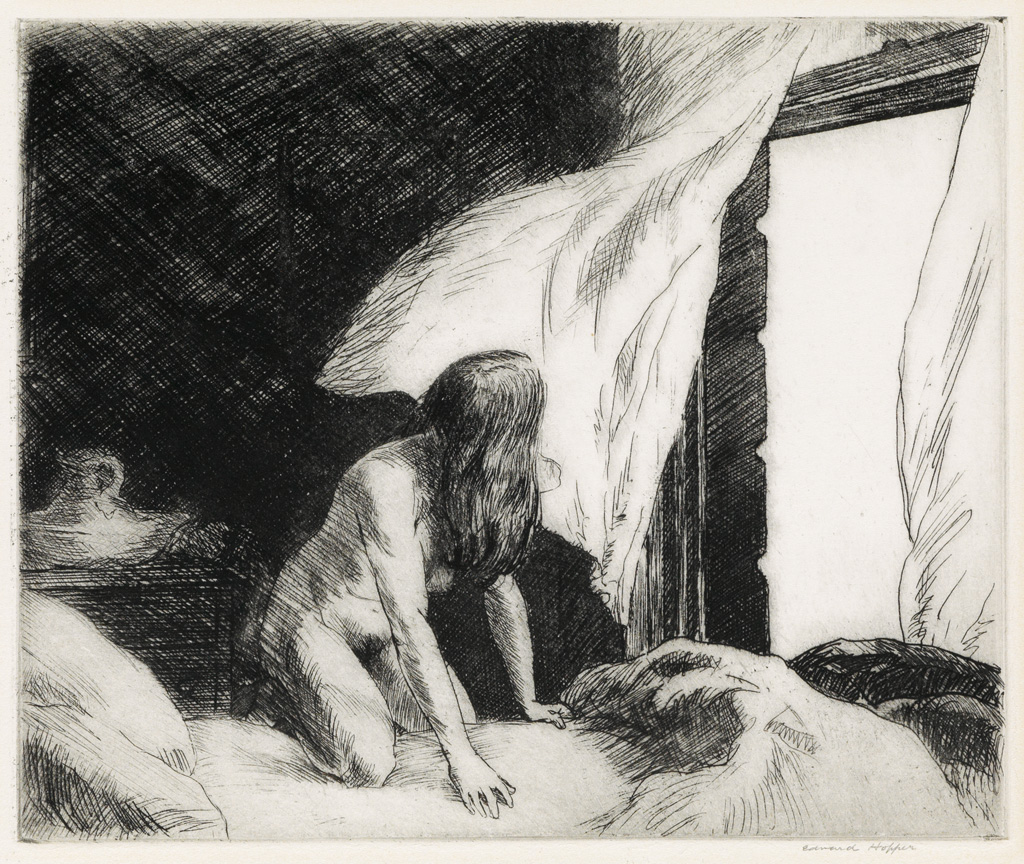

Evening Wind.

Etching, 1921. 180x212 mm; 7x8 1/4 inches, full margins. Signed in pencil, lower right, and titled and priced ("$30") by the artist in pencil, lower left. Partial Umbria watermark. A brilliant, richly-inked impression of this extremely scarce, important etching, with very strong contrasts, with all the details distinct and with no sign of wear.

According to an account by Hopper regarding his printing methods, "The best prints were done on an Italian paper called 'Umbria' and was the whitest paper I could get. The ink was an intense black that I sent for to Kimber in London, as I could not get an intense enough black here. I had heard so much of the beauty of old paper that I tried some 18th century ledger paper, but it did not give me the contrast and brilliance that I wished, and I did not use it," (Levin, Edward Hopper, The Complete Prints, New York, 1979, page 11).

Hopper (1882-1967) was born in Nyack, New York, just north of New York City. After briefly studying at the Correspondence School of Illustrating (1899-1900), he attended the New School of Art from 1900 to 1906. Hopper studied painting and life drawing under Kenneth Hayes Miller, Robert Henri and William Merritt Chase alongside classmates George Bellows, Guy Pène du Bois and Rockwell Kent. At 24 years old, Hopper traveled to Paris, where he stayed for over a year (he returned to Europe again in 1909 and 1910). These European trips were crucial to his development as an artist, and even though he never returned to Paris, he portrayed a romanticized ideal of the place in many of his works until 1924, at which time he ceased using overt French imagery altogether. While many American artists who visited Paris during this time were most struck by the avant-garde movements of Fauvism and Cubism, Hopper paid them little attention and instead studied Degas and Manet, as well as Rembrandt and other Old Masters.

Hopper never chose to characterize himself as an illustrator or printmaker, preferring to be known as a painter, but ironically he found commercial success and a livelihood through both of these downplayed endeavors. Hopper began working as an illustrator in 1905 with C. C. Phillips & Company, New York, and greatly supplemented his income through illustration work through the early 1900s. He did not find sound financial footing through sales of his paintings until after 1924, following a sold out exhibition of his work, at Rehn Gallery, New York.

Hopper's first foray into printmaking came at the encouragement of then-fellow illustrator Martin Lewis, in 1915 (see lots 254-261), who instructed him on the technical aspects of the medium. Despite receiving this initial instruction on printmaking from Lewis, their styles were markedly different: Lewis employed a variety of complicated techniques to obtain his desired tonal effects, while Hopper had a much simpler approach, only ever working in etching and drypoint. (Before he began etching in 1915, Hopper produced several monotypes, a medium viewed as an intermediary step between painting and printing.) Lewis focused on printmaking throughout his artistic career, while Hopper produced approximately 70 prints over a relatively short period of time. His career as an etcher was particularly short-lived and essentially ended in 1923; in 1928 he made his final prints, two drypoints, before abandoning printmaking altogether to focus on painting.

Hopper quickly mastered etching and drypoint. He had a relatively simple and steadfast preference when it came to printmaking: very black ink on very white paper; plates that were deeply bitten and clean-wiped; producing impressions that came out inky with brilliant contrasts. While creating seemingly straightforward, realist compositions, Hopper imbued his scenes with mood and emotion, aptly capturing the intangible quality of a fleeting moment. His work is characterized by a sense of stillness and isolation, which he often dramatized with the use of heavy chiaroscuro and strong, dark hatching, such as in Evening Wind, one of his most celebrated etchings. The image of a lone woman before a window appears repeatedly in his oeuvre, and is an arrangement employed by one of his greatly-admired influences, Degas. Windows crop up frequently in Hopper's work, as symbols of the contrast between quiet interior moments and the busy outside world. Psychologically, Hopper's figures are often caught in moments of contemplation or seeming boredom--scenes of stillness indicative of loneliness and weariness.

Hopper's rapidly-gained proficiency as an etcher, his unique style and perspective, and the number of absolutely masterful prints that he created over his short career as a printmaker earn him a place as one of the most important American graphic artists of the 20th century. Zigrosser 9; Levin 77.

Evening Wind.

Etching, 1921. 180x212 mm; 7x8 1/4 inches, full margins. Signed in pencil, lower right, and titled and priced ("$30") by the artist in pencil, lower left. Partial Umbria watermark. A brilliant, richly-inked impression of this extremely scarce, important etching, with very strong contrasts, with all the details distinct and with no sign of wear.

According to an account by Hopper regarding his printing methods, "The best prints were done on an Italian paper called 'Umbria' and was the whitest paper I could get. The ink was an intense black that I sent for to Kimber in London, as I could not get an intense enough black here. I had heard so much of the beauty of old paper that I tried some 18th century ledger paper, but it did not give me the contrast and brilliance that I wished, and I did not use it," (Levin, Edward Hopper, The Complete Prints, New York, 1979, page 11).

Hopper (1882-1967) was born in Nyack, New York, just north of New York City. After briefly studying at the Correspondence School of Illustrating (1899-1900), he attended the New School of Art from 1900 to 1906. Hopper studied painting and life drawing under Kenneth Hayes Miller, Robert Henri and William Merritt Chase alongside classmates George Bellows, Guy Pène du Bois and Rockwell Kent. At 24 years old, Hopper traveled to Paris, where he stayed for over a year (he returned to Europe again in 1909 and 1910). These European trips were crucial to his development as an artist, and even though he never returned to Paris, he portrayed a romanticized ideal of the place in many of his works until 1924, at which time he ceased using overt French imagery altogether. While many American artists who visited Paris during this time were most struck by the avant-garde movements of Fauvism and Cubism, Hopper paid them little attention and instead studied Degas and Manet, as well as Rembrandt and other Old Masters.

Hopper never chose to characterize himself as an illustrator or printmaker, preferring to be known as a painter, but ironically he found commercial success and a livelihood through both of these downplayed endeavors. Hopper began working as an illustrator in 1905 with C. C. Phillips & Company, New York, and greatly supplemented his income through illustration work through the early 1900s. He did not find sound financial footing through sales of his paintings until after 1924, following a sold out exhibition of his work, at Rehn Gallery, New York.

Hopper's first foray into printmaking came at the encouragement of then-fellow illustrator Martin Lewis, in 1915 (see lots 254-261), who instructed him on the technical aspects of the medium. Despite receiving this initial instruction on printmaking from Lewis, their styles were markedly different: Lewis employed a variety of complicated techniques to obtain his desired tonal effects, while Hopper had a much simpler approach, only ever working in etching and drypoint. (Before he began etching in 1915, Hopper produced several monotypes, a medium viewed as an intermediary step between painting and printing.) Lewis focused on printmaking throughout his artistic career, while Hopper produced approximately 70 prints over a relatively short period of time. His career as an etcher was particularly short-lived and essentially ended in 1923; in 1928 he made his final prints, two drypoints, before abandoning printmaking altogether to focus on painting.

Hopper quickly mastered etching and drypoint. He had a relatively simple and steadfast preference when it came to printmaking: very black ink on very white paper; plates that were deeply bitten and clean-wiped; producing impressions that came out inky with brilliant contrasts. While creating seemingly straightforward, realist compositions, Hopper imbued his scenes with mood and emotion, aptly capturing the intangible quality of a fleeting moment. His work is characterized by a sense of stillness and isolation, which he often dramatized with the use of heavy chiaroscuro and strong, dark hatching, such as in Evening Wind, one of his most celebrated etchings. The image of a lone woman before a window appears repeatedly in his oeuvre, and is an arrangement employed by one of his greatly-admired influences, Degas. Windows crop up frequently in Hopper's work, as symbols of the contrast between quiet interior moments and the busy outside world. Psychologically, Hopper's figures are often caught in moments of contemplation or seeming boredom--scenes of stillness indicative of loneliness and weariness.

Hopper's rapidly-gained proficiency as an etcher, his unique style and perspective, and the number of absolutely masterful prints that he created over his short career as a printmaker earn him a place as one of the most important American graphic artists of the 20th century. Zigrosser 9; Levin 77.

Exhibition Hours

Exhibition Hours

Aliquam vulputate ornare congue. Vestibulum maximus, libero in placerat faucibus, risus nisl molestie massa, ut maximus metus lectus vel lorem.