Sale 2607 - Lot 127

Price Realized: $ 2,800

Price Realized: $ 3,500

?Final Price Realized includes Buyer’s Premium added to Hammer Price

Estimate: $ 300 - $ 500

Meriwether, Lide Parker Smith (1829-1913)

Autograph Manuscript of Lecture Notes.

1880s.

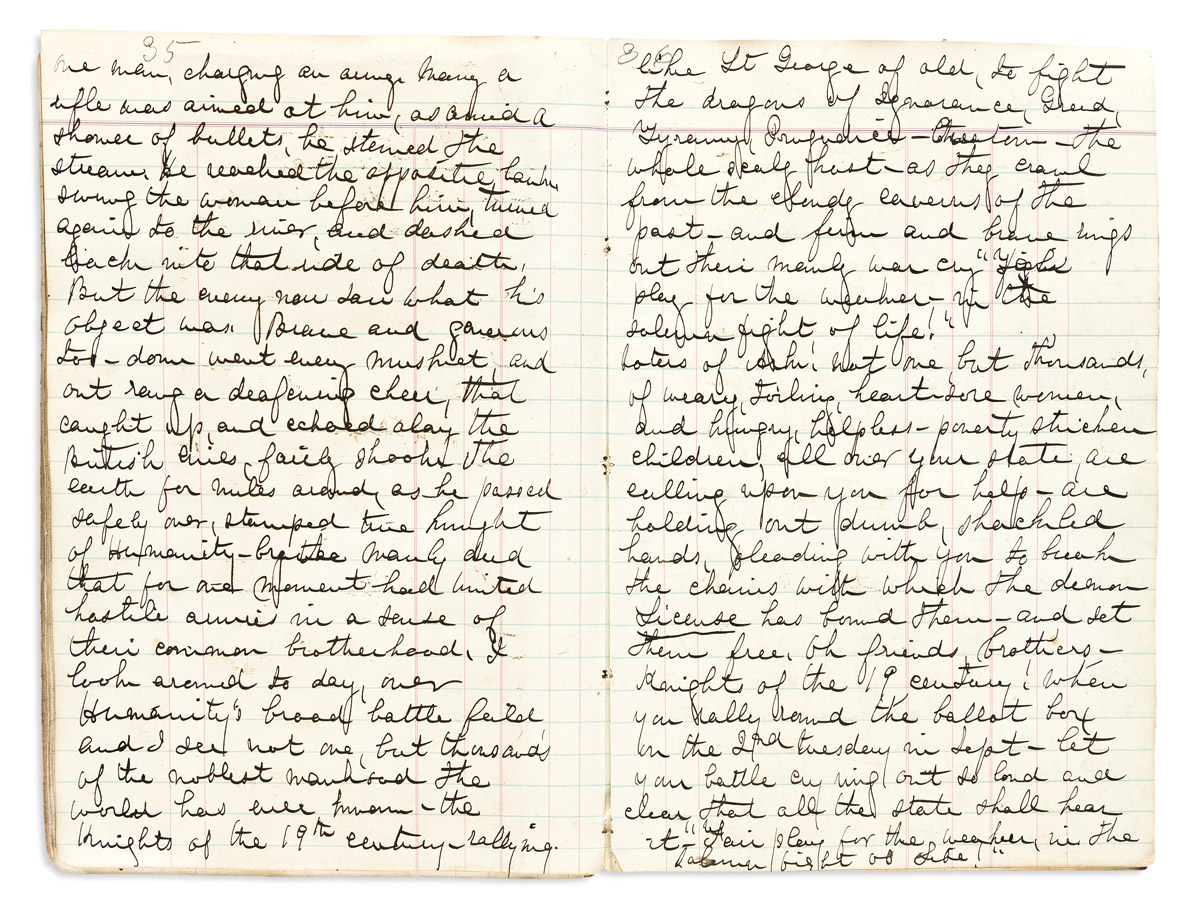

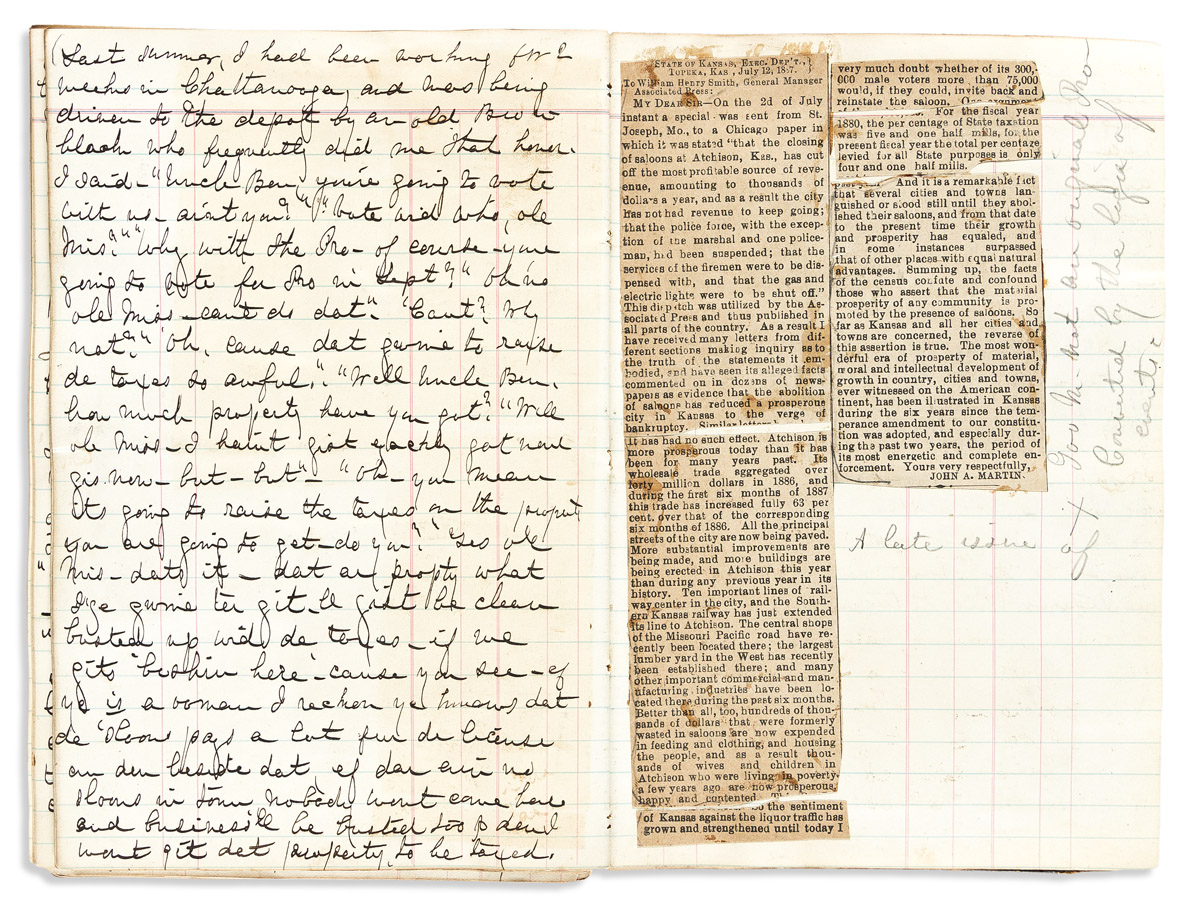

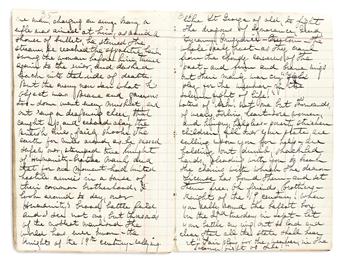

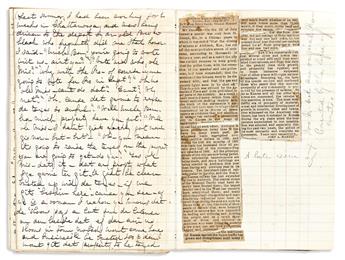

Octavo-format lined journal originally used (barely) as an account book, repurposed by the author containing handwritten notes and clippings, occupying approximately 144 pages, easily legible and densely inscribed, on topics of Meriwether's various social causes for presentation in public lectures; black morocco boards, both detached, lacking spine, in need of resewing; pages somewhat wavy where clippings have been pasted, with occasional glue discoloration, a very good candidate for restoration, 8 1/2 x 5 3/4 in.

Meriwether was a strong vocal advocate for women's rights whose work contributed substantially to the first wave of feminism. The platform of the Tennessee Woman's Christian Temperance Union, which she served as president from 1884 to 1897, included planks beyond those suggested by its name. Meriwether advocated for raising the age of sexual consent (which was ten years old), woman's suffrage, female education, equal pay, and equal rights under the law, to great success. She also actively recruited Black women to join the WCTU, and presided over interracial meetings of the group in Memphis in the 1880s.

In this manuscript, which begins with remarks for a speech delivered at the end of 1888, Meriwether's prepared text is interspersed with clippings to be read out loud in support of her points. For example, she includes a newspaper piece on a filthy dive bar downtown on Mulberry Street in New York City. Frequented by poor women who buy stale beer mixed with soda water, these "pitiable wrecks" would drink themselves into a stupor, and then sleep on the floor. Our orator includes it to drive home her point. Meriwether felt that women of privilege were complicit in the degraded status of their sisters when they fail to take political action. Without equal education, equal work opportunities, and equal pay, how can indigent women provide for themselves? She does not mince words. "Oh woman! living in comfortable ease! is it nothing to you that thousands of your sisters, hounded into the depths by poverty, ignorance, and licensed greed, are battling and sinking in these black waves of moral and social degradation and death?"

The talk that begins on page 37 of the current manuscript is titled, "Waste Not, Want Not," and is clearly written to address a Black audience. Meriwether writes in part, "I have always felt that our race owed to yours a peculiar debt of gratitude, the like of which has never been known in the history of any other nation." Raised in Virginia, she goes on to describe her warm feelings about the Black woman who tended and raised her from infancy, and then transitions into a description of the successes of people of color in the south. "I want to see you all prosperous, and happy, and good. I rejoice always to see schoolhouses going up for you. I love to see your nice churches, your comfortable schoolhouses, your kind, well-educated teachers, your honest, straightforward God fearing preachers. I love to go to your school examinations, and see your exhibitions, and to see how fast your children learn & how bright they are, and to hear them sing & play and to look at their pretty paintings & embroideries; and to know that they are improving their advantages and in time they will be useful & honorable men & women, a blessing and an honor to their parents, their country, & their race."

Autograph Manuscript of Lecture Notes.

1880s.

Octavo-format lined journal originally used (barely) as an account book, repurposed by the author containing handwritten notes and clippings, occupying approximately 144 pages, easily legible and densely inscribed, on topics of Meriwether's various social causes for presentation in public lectures; black morocco boards, both detached, lacking spine, in need of resewing; pages somewhat wavy where clippings have been pasted, with occasional glue discoloration, a very good candidate for restoration, 8 1/2 x 5 3/4 in.

Meriwether was a strong vocal advocate for women's rights whose work contributed substantially to the first wave of feminism. The platform of the Tennessee Woman's Christian Temperance Union, which she served as president from 1884 to 1897, included planks beyond those suggested by its name. Meriwether advocated for raising the age of sexual consent (which was ten years old), woman's suffrage, female education, equal pay, and equal rights under the law, to great success. She also actively recruited Black women to join the WCTU, and presided over interracial meetings of the group in Memphis in the 1880s.

In this manuscript, which begins with remarks for a speech delivered at the end of 1888, Meriwether's prepared text is interspersed with clippings to be read out loud in support of her points. For example, she includes a newspaper piece on a filthy dive bar downtown on Mulberry Street in New York City. Frequented by poor women who buy stale beer mixed with soda water, these "pitiable wrecks" would drink themselves into a stupor, and then sleep on the floor. Our orator includes it to drive home her point. Meriwether felt that women of privilege were complicit in the degraded status of their sisters when they fail to take political action. Without equal education, equal work opportunities, and equal pay, how can indigent women provide for themselves? She does not mince words. "Oh woman! living in comfortable ease! is it nothing to you that thousands of your sisters, hounded into the depths by poverty, ignorance, and licensed greed, are battling and sinking in these black waves of moral and social degradation and death?"

The talk that begins on page 37 of the current manuscript is titled, "Waste Not, Want Not," and is clearly written to address a Black audience. Meriwether writes in part, "I have always felt that our race owed to yours a peculiar debt of gratitude, the like of which has never been known in the history of any other nation." Raised in Virginia, she goes on to describe her warm feelings about the Black woman who tended and raised her from infancy, and then transitions into a description of the successes of people of color in the south. "I want to see you all prosperous, and happy, and good. I rejoice always to see schoolhouses going up for you. I love to see your nice churches, your comfortable schoolhouses, your kind, well-educated teachers, your honest, straightforward God fearing preachers. I love to go to your school examinations, and see your exhibitions, and to see how fast your children learn & how bright they are, and to hear them sing & play and to look at their pretty paintings & embroideries; and to know that they are improving their advantages and in time they will be useful & honorable men & women, a blessing and an honor to their parents, their country, & their race."

Exhibition Hours

Exhibition Hours

Aliquam vulputate ornare congue. Vestibulum maximus, libero in placerat faucibus, risus nisl molestie massa, ut maximus metus lectus vel lorem.