Sale 2441 - Lot 256

Price Realized: $ 15,000

Price Realized: $ 18,750

?Final Price Realized includes Buyer’s Premium added to Hammer Price

Estimate: $ 20,000 - $ 30,000

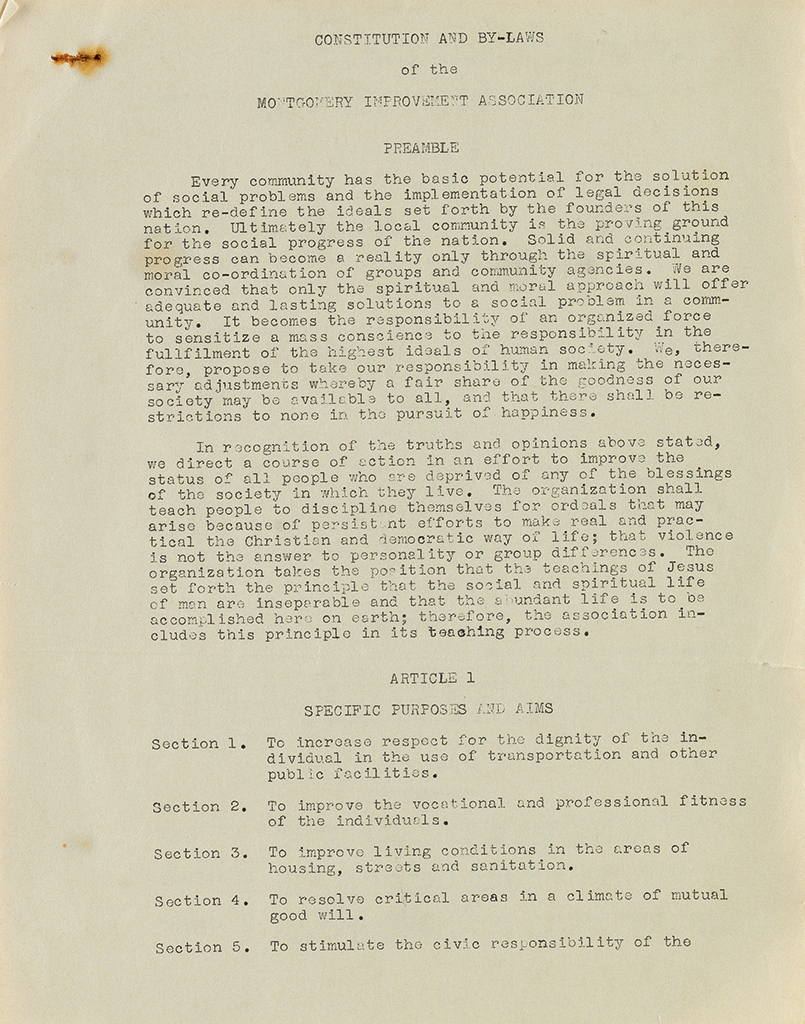

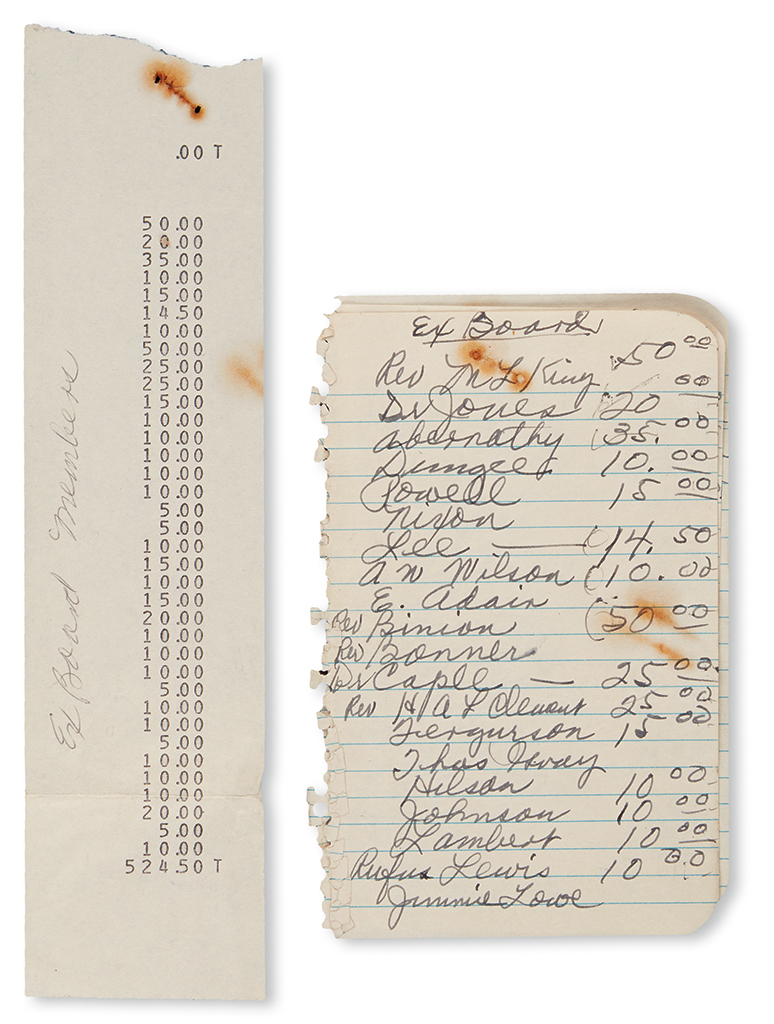

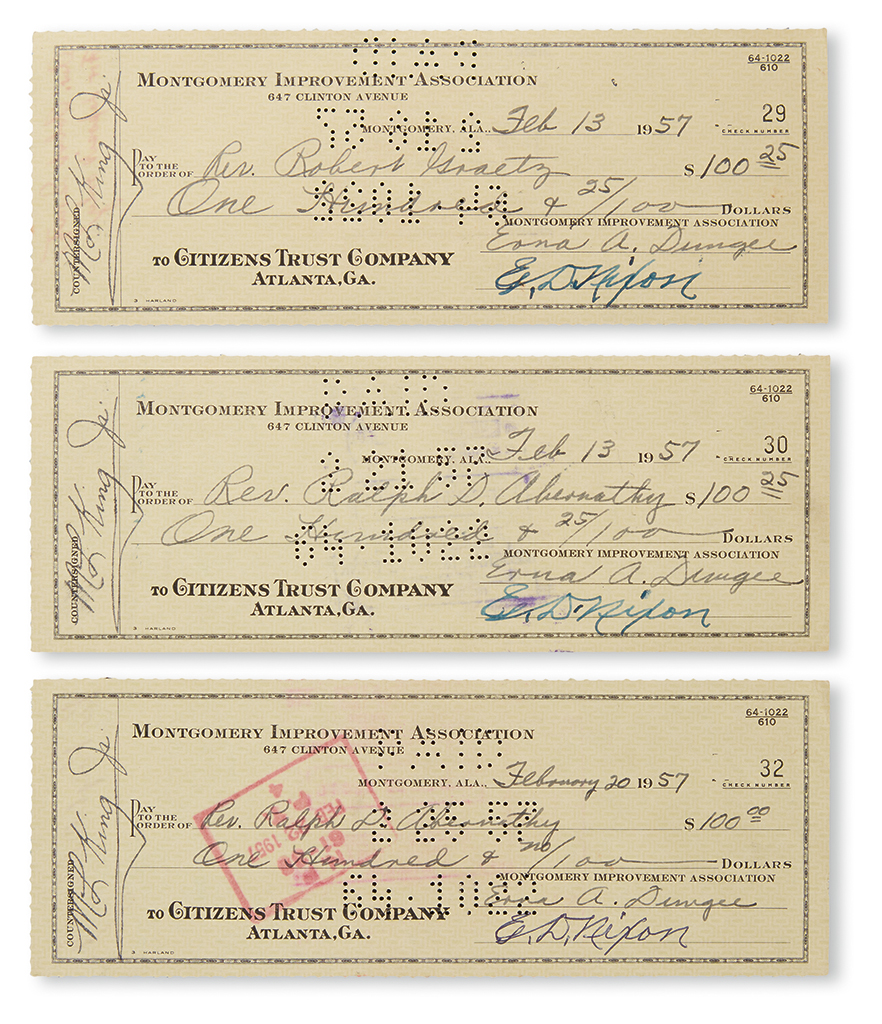

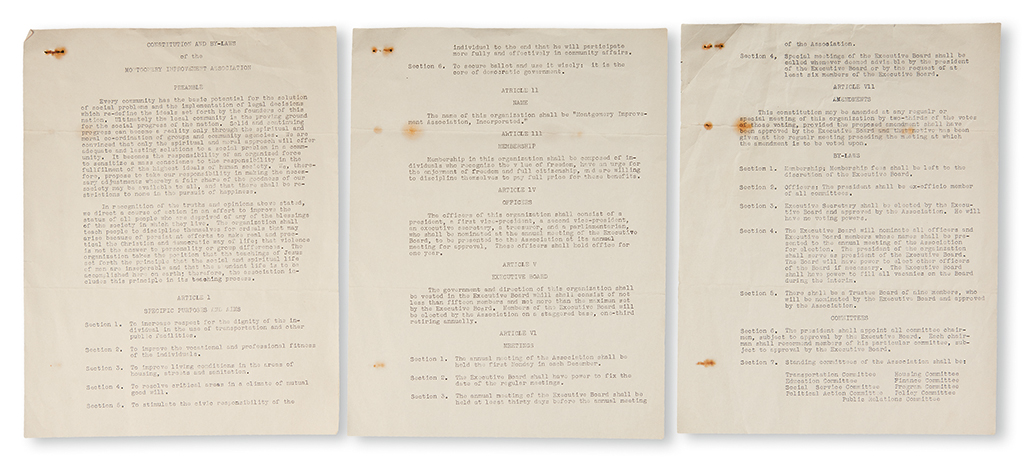

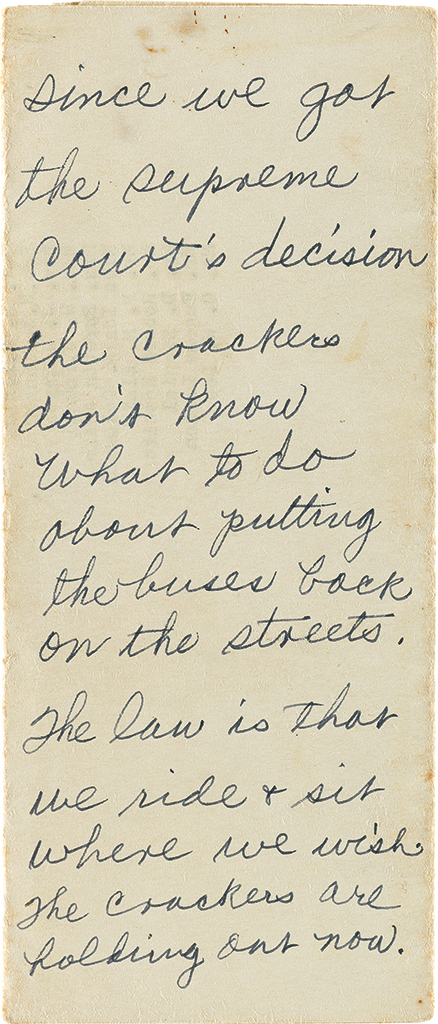

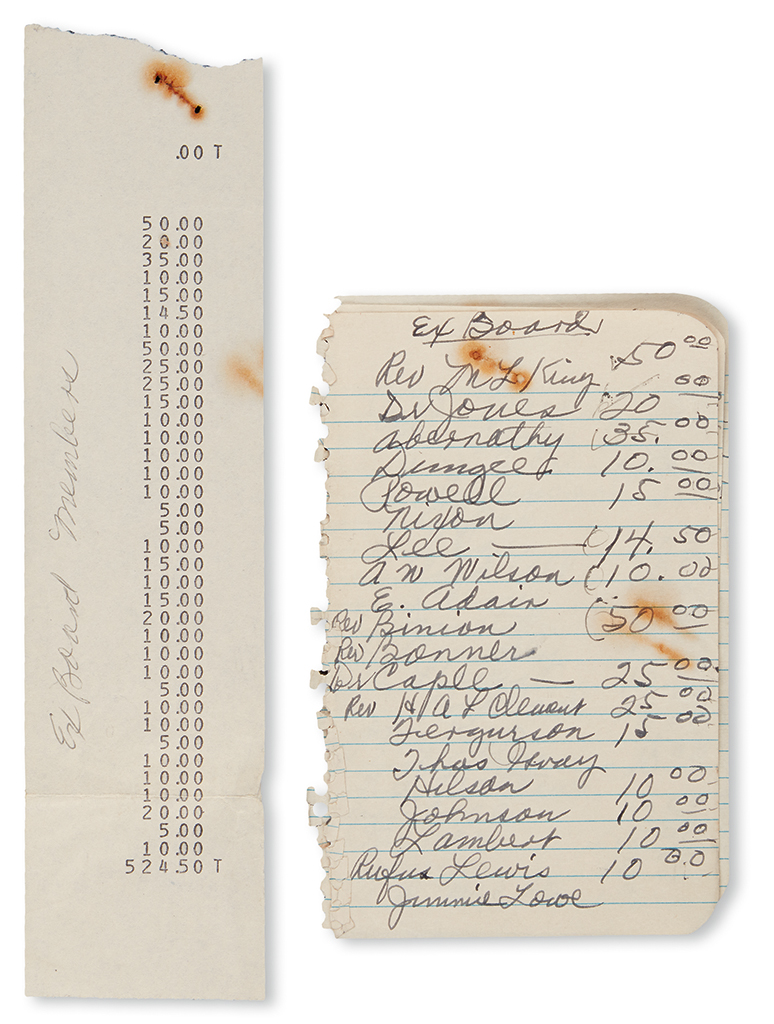

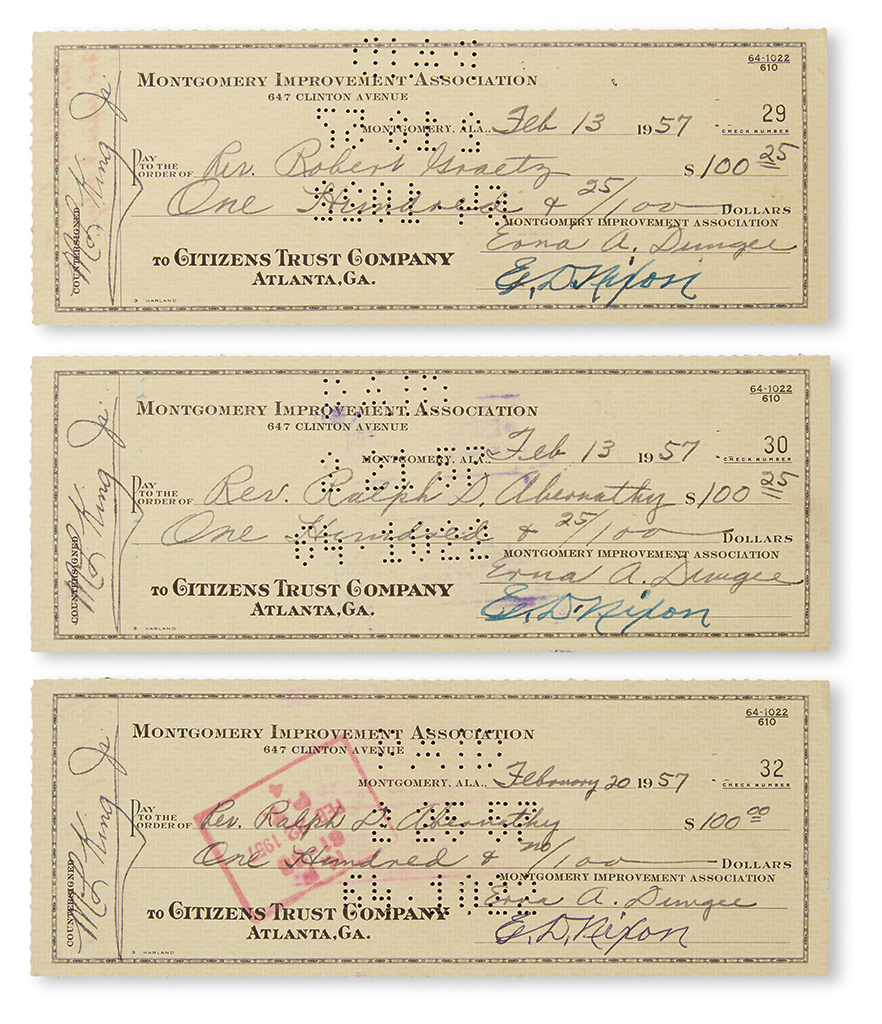

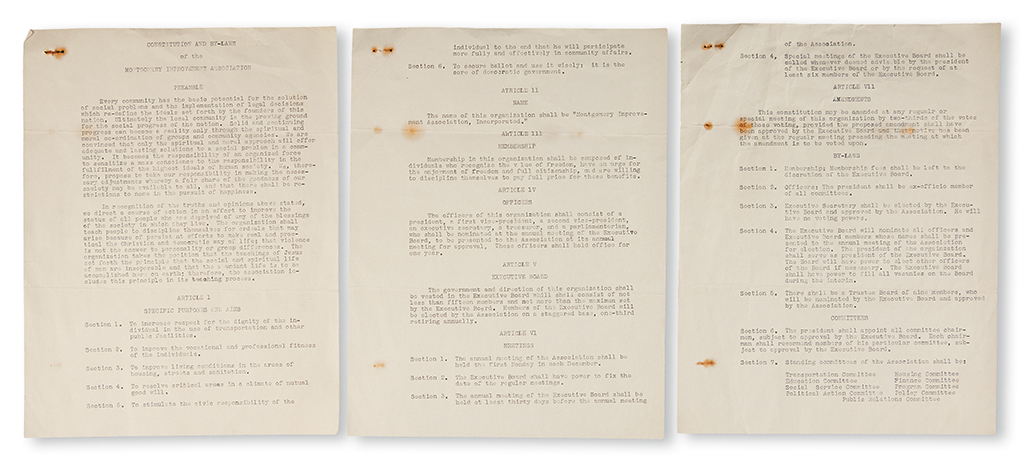

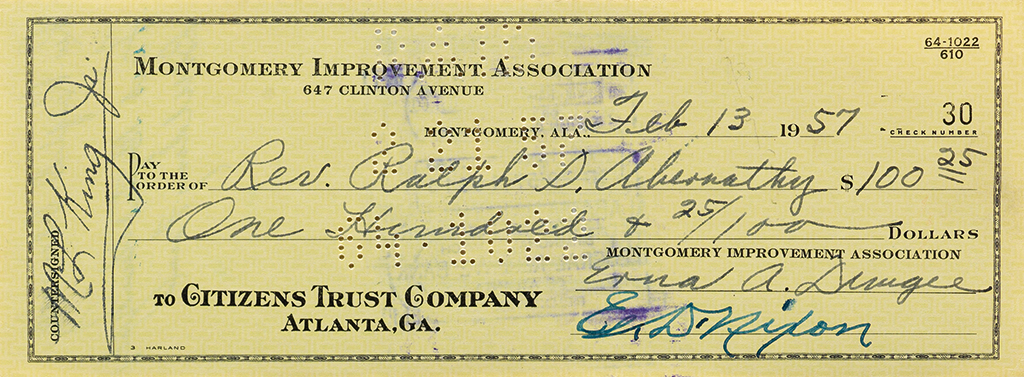

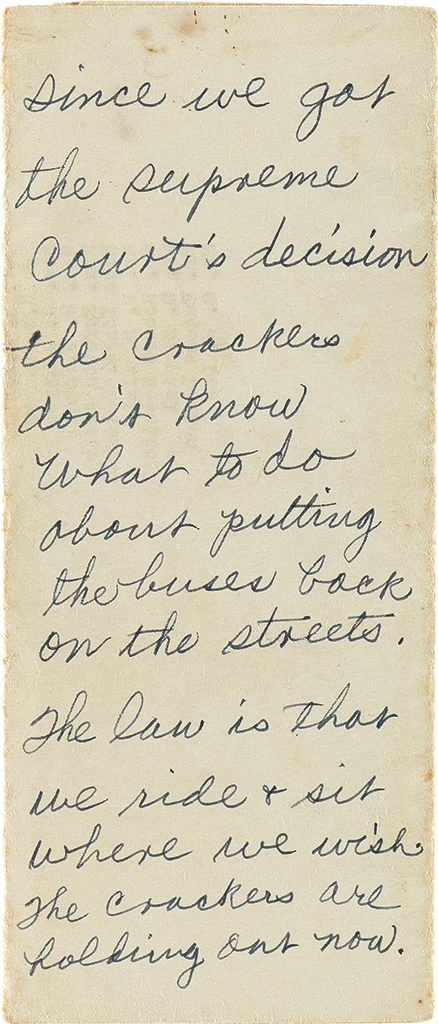

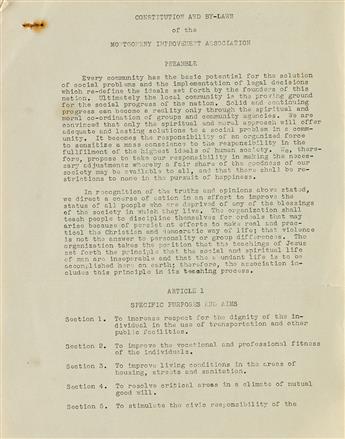

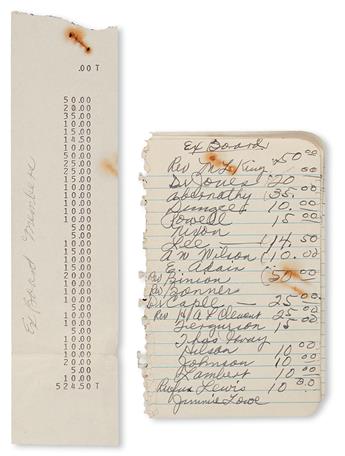

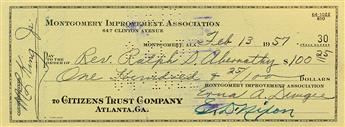

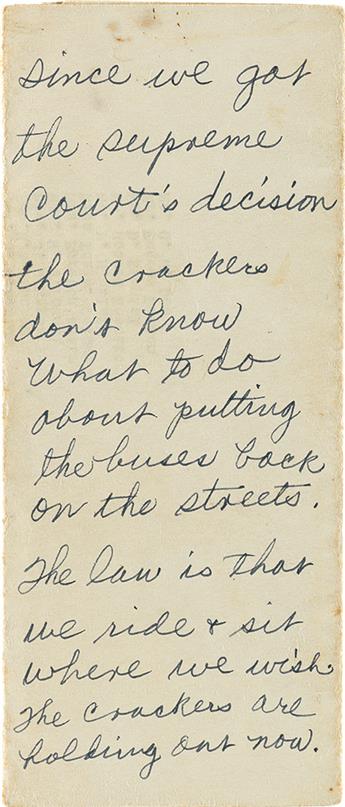

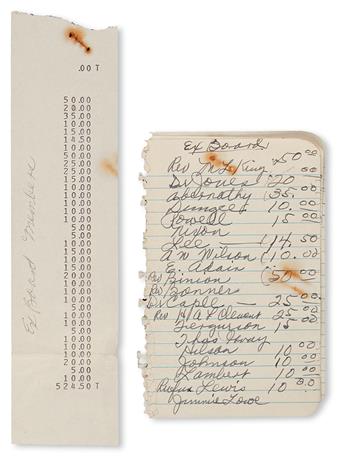

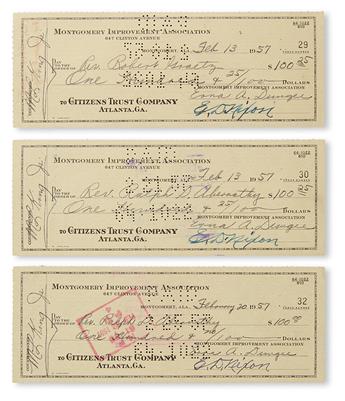

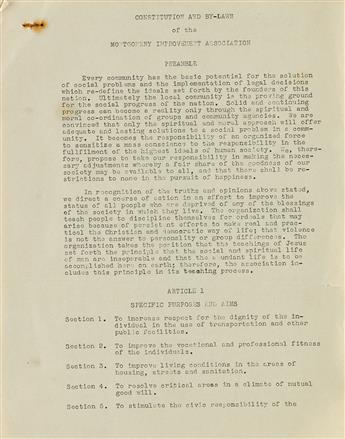

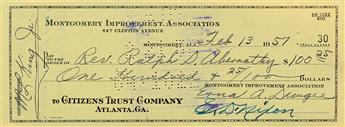

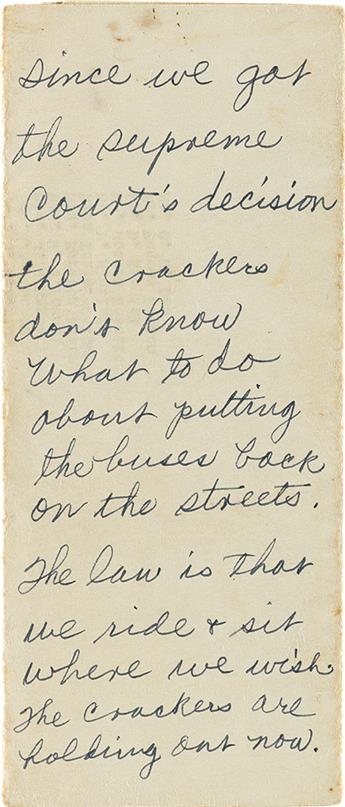

(CIVIL RIGHTS.) KING, MARTIN LUTHER JR, RALPH ABERNATHY, E. D. NIXON, ERNA DUNGEE, ET AL. A large collection of formative papers from the Montgomery Improvement Association. Contained in two very large ring binders; one with the checks (nearly 600) from the MIA from its earliest days through the 1960's; the other with over 500 pieces, including: the Constitution and By-laws of the Montgomery Improvement Association, the original handwritten list of the "Ex.[ecutive] Board," with their respective salaries; the financial statement at the time of the Supreme Court ruling on the Boycott; a hand written note on the back of same, written by Erna Dungee observing that "The Crackers don't know what to do about putting the buses back on the street." Montgomery, AL, 1955-1963

Additional Details

an extraordinary archive, rich in detail with hundreds of pieces; shedding new light on this seminal community movement, which heralded the beginnings of the modern civil rights struggle. On December 1st, 1955 after a long, hard day on her feet; Rosa Parks, a seamstress at a Montgomery Fair department store, boarded her usual Cleveland Avenue bus, and was happy to find a seat. Her subsequent refusal to give that seat up was to change the course of modern history.

The day after her arrest, Montgomery authorities were convinced that Parks had been a "plant", part of an NAACP plot to stir up trouble. But her act, according to Martin Luther King Jr. had been "an individual expression of a timeless longing for human dignity and freedom. . . . she was not 'planted' there by the NAACP or any other organization; she was planted there by her personal sense of dignity and self respect." (Stride Toward Freedom, page 44). Parks, a former secretary of a local NAACP, made the necessary phone call and E.D. Nixon, a local activist, came and signed her bond. In his first book, "Stride Toward Freedom," King describes the call he received from Nixon the day after the incident: "I listened deeply shocked, as he described the humiliating incident. 'We have taken this thing too long already,' Nixon concluded, his voice trembling. I feel the time has come to boycott the buses.'"

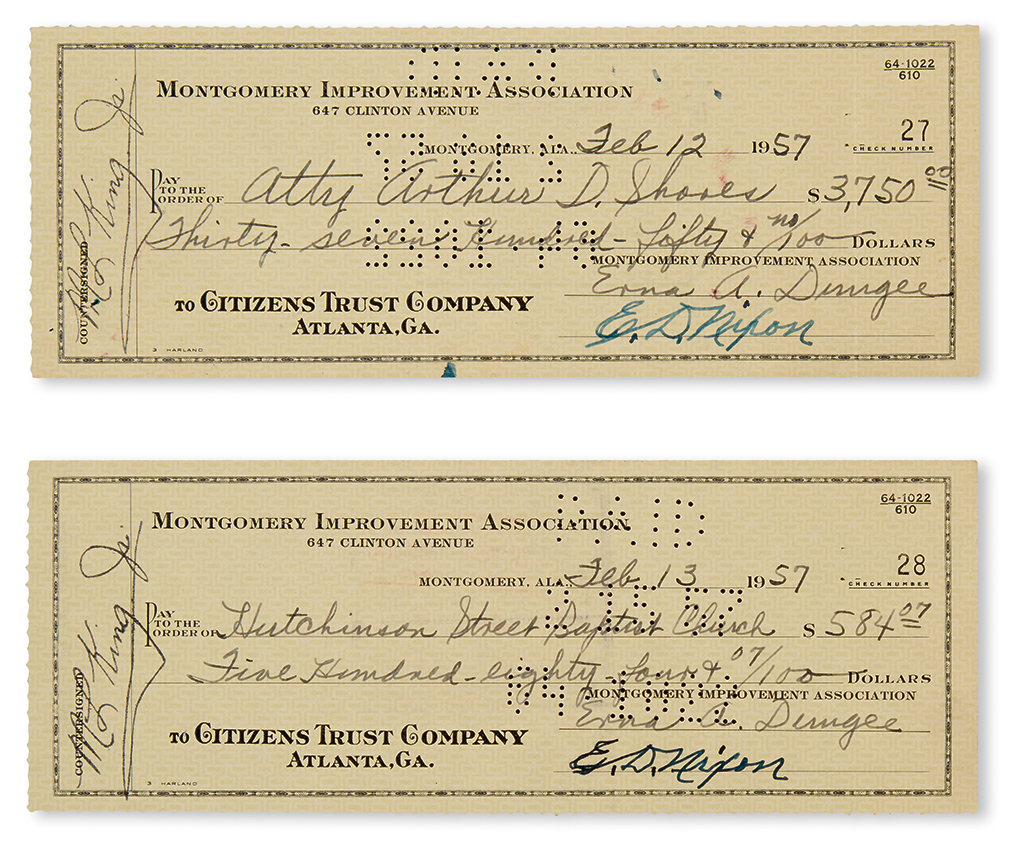

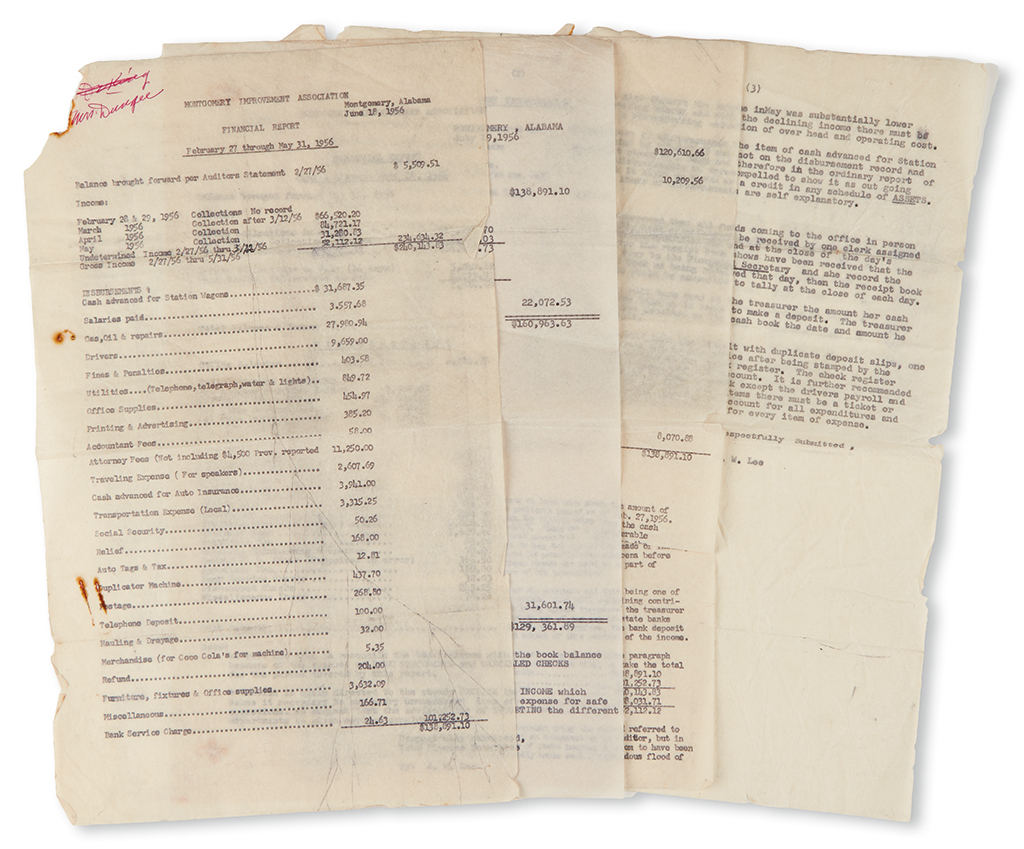

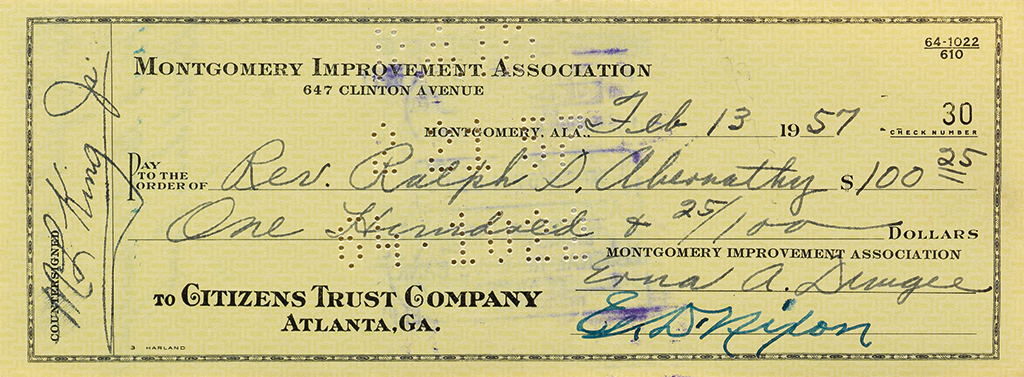

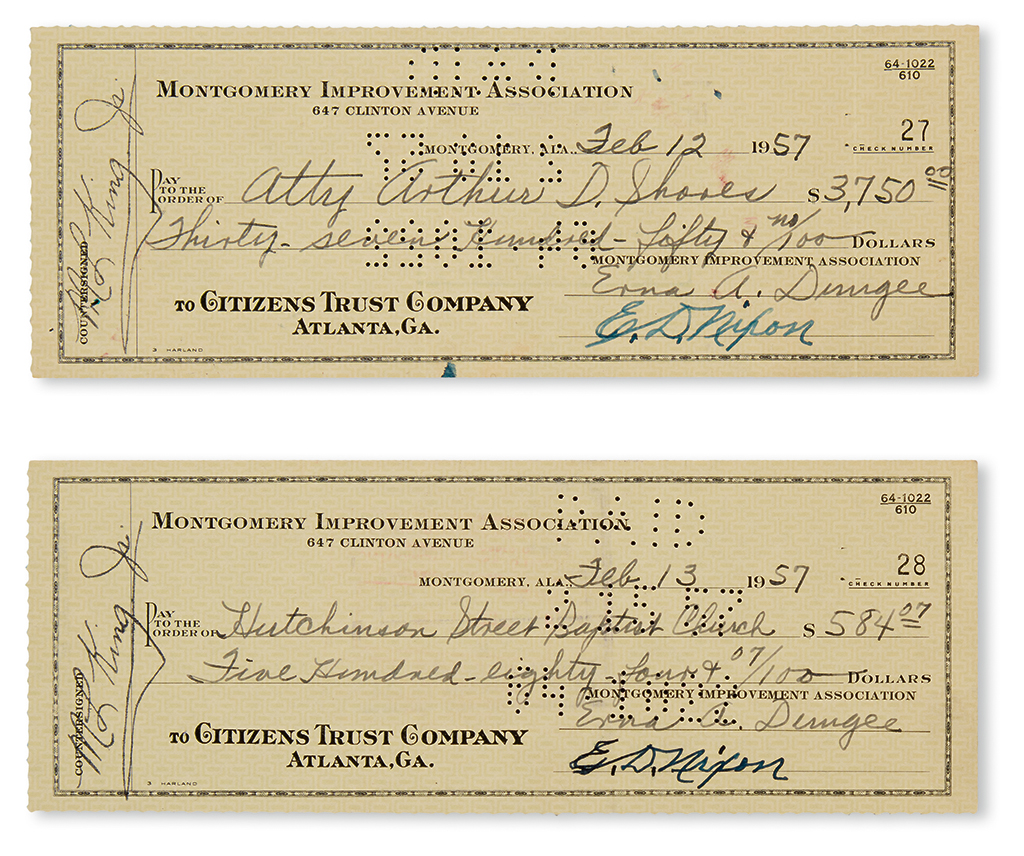

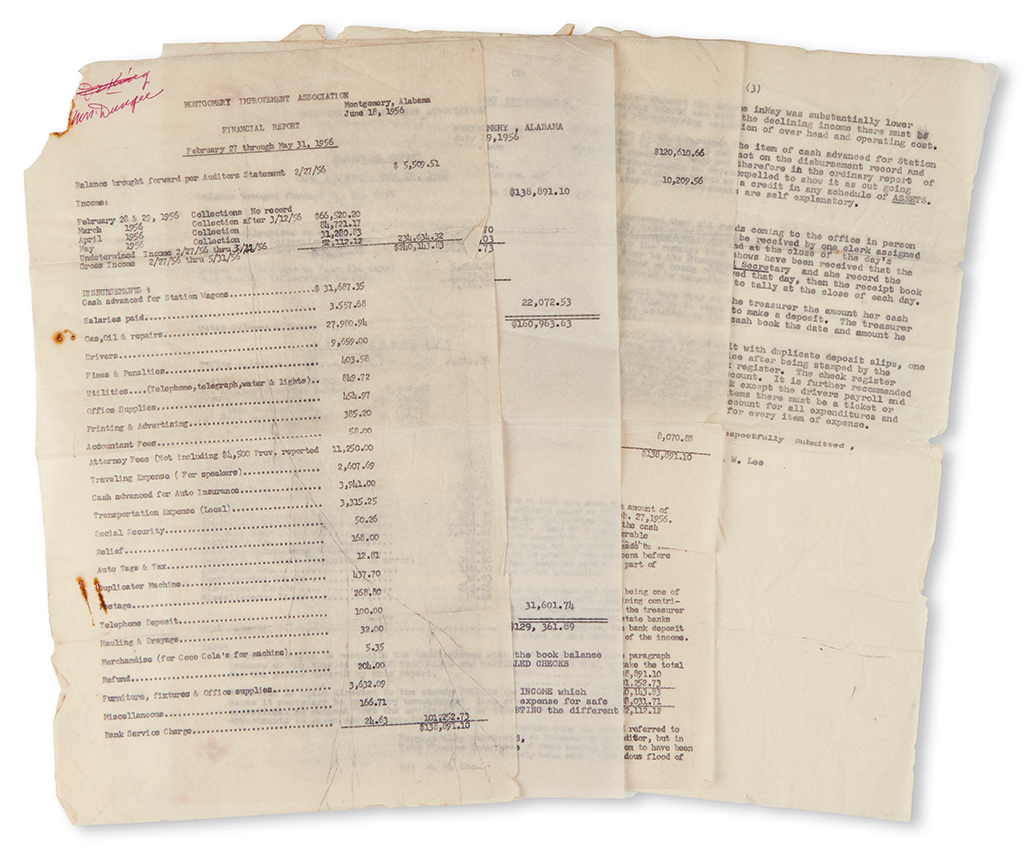

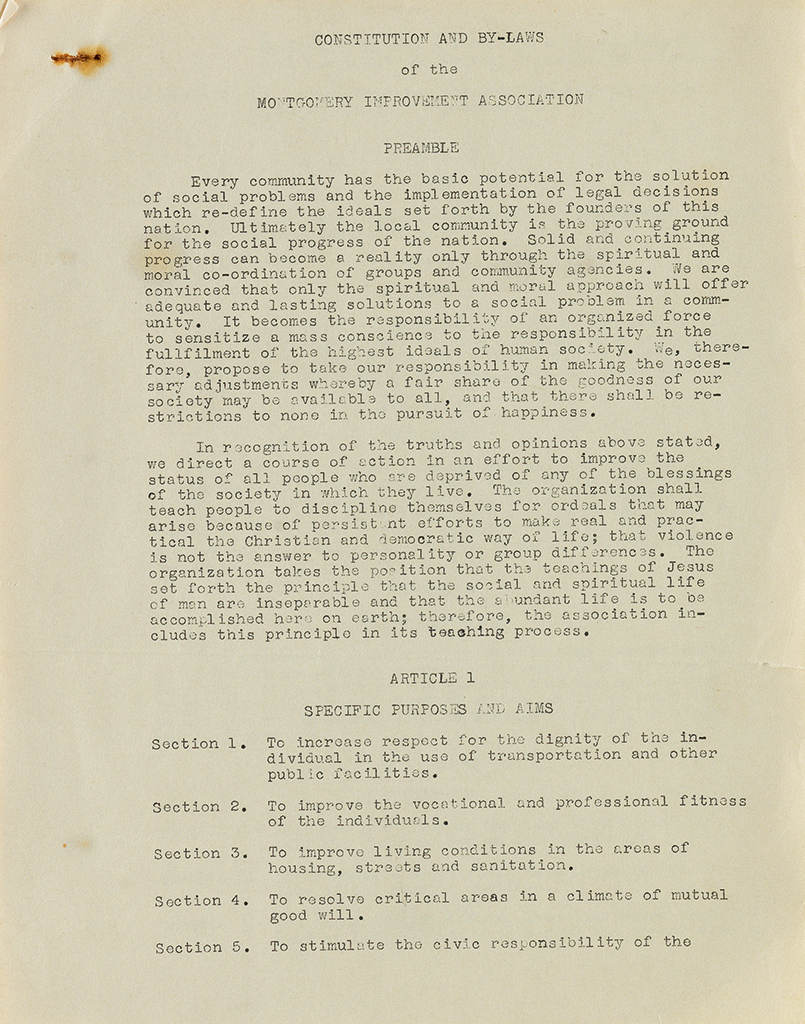

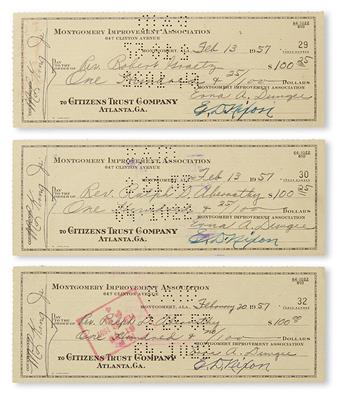

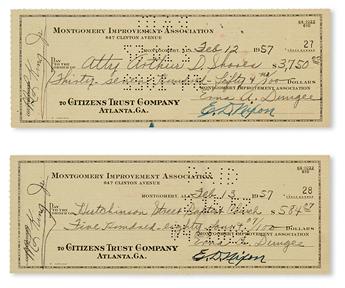

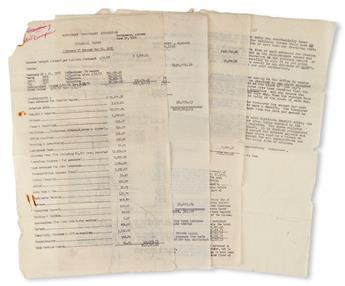

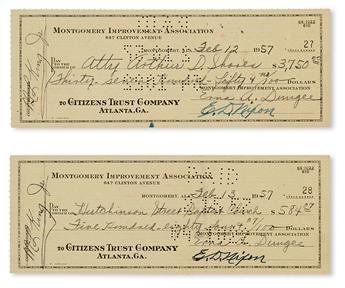

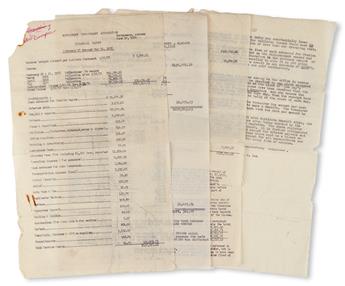

Within 72 hours the Montgomery Improvement Association was born, and a total boycott of Montgomery's buses began. A group of ministers and activists, led by King, Abernathy, Nixon, and Erna Dungee cobbled together a plan that would get Montgomery's 17,500 African American workers to and from their jobs during the boycott. At first, over two hundred Black cabbies offered to charge the same ten cents the bus fare would have been. But Montgomery's authorities, hoping to force blacks back to their buses, said that legally the cabbies had to charge each rider the minimum 45 cents per ride. Initially, individuals volunteered their cars, and pickup and drop-off zones were agreed upon. Surprisingly, many white women reluctant to lose their maids picked them up themselves. But a better plan had to be put in motion, and it was decided in April the MIA would acquire a fleet of station wagons and drivers. Within the four months of its creation, a great deal of money had been flowing in to the MIA from all over the country and from international sources as far off as Japan. The financial report shows that the MIA paid nearly $32,000 for a fleet of station wagons. Expenses for everything down to gas, oil and repairs for the vehicles is laid out. Additionally, there is a detailed "Report of the Committee on Station Wagons." That June financial report details everything regarding the purchase of the station wagons, and all of the other expenses of the MIA. There are careful records plus the checks that were written to all who were on salary, or for services rendered. A number of the earliest checks are co-signed by Martin Luther King Jr. (or in some cases his secretary Maude Ballou). The original constitution and by-laws for the MIA is present as well as the original ribbon copy of their first financial report, dated June 18, 1956 (in red ink at the top "Mrs Dungee"). There is also a mimeograph copy of their financial report, which is concurrent with the Supreme Court ruling in their favor, dated September 13, 1956. On the back of this report, Dungee has written "Since we got the Supreme Court's decision the crackers don't know what to do about putting the buses back on the streets. (!) The Law is that we ride + sit where we wish. The crackers are holding out now."

There are original citations for minor traffic infractions from the bus drivers, meant to harass the MIA, along with the records of payment. Together with all of the hand-written material, are several interesting piece of printed matter, such as King's "Our Struggle," printed and distributed by the MIA, and a scarce copy of the Third Annual Institute on Non-Violence and Social Change, an eight page pamphlet published by the MIA in December of 1958.

Sympathetic reaction, both nationally and internationally came surprisingly fast in the form of donations from widely diverse sources. The people of Boley Oklahoma, an affluent and entirely black community got together and opened an account for the MIA with a deposit for $5000!

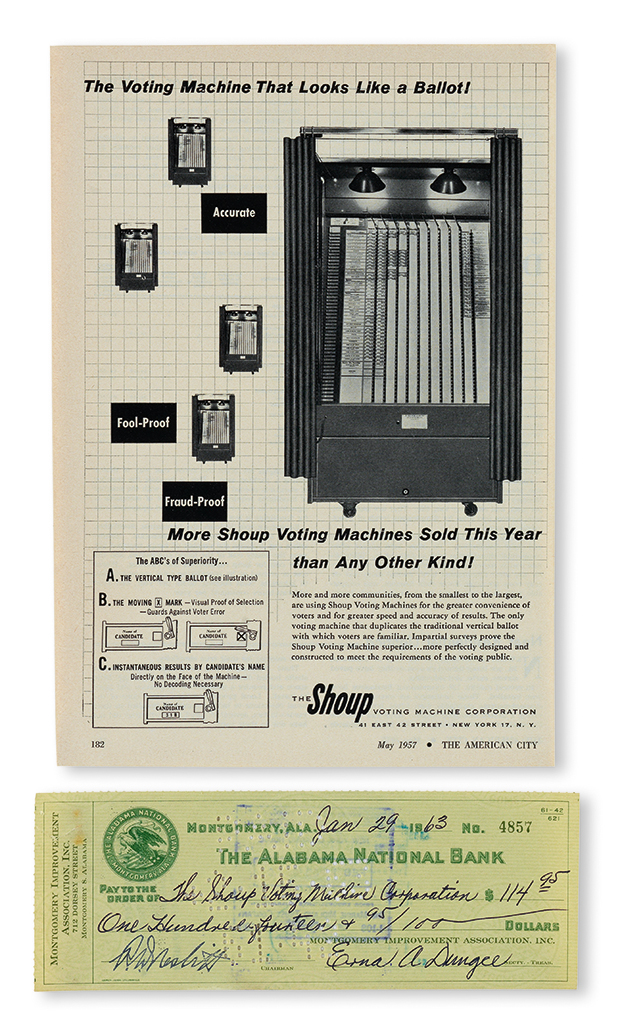

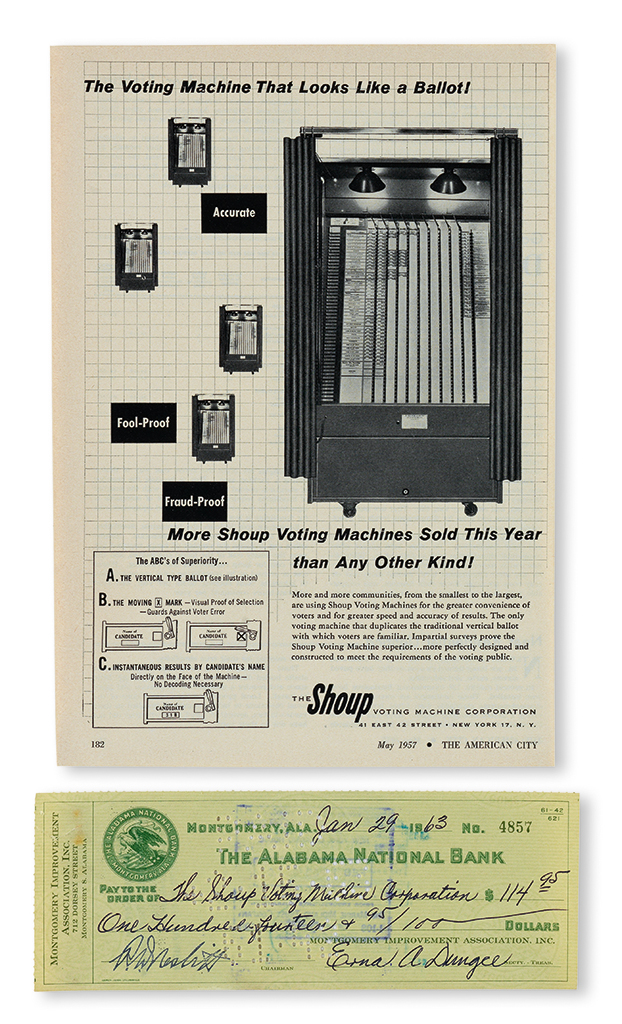

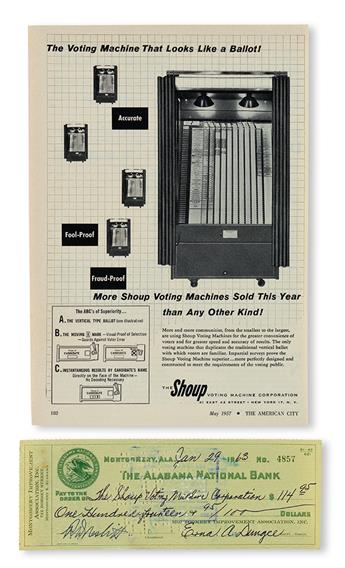

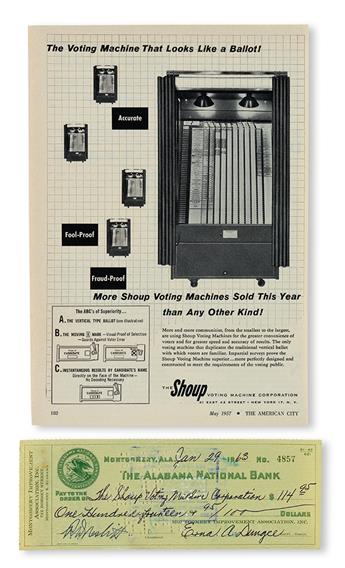

The nearly 600 checks written by the MIA help to tell the story. A 1963 check written to the Shoup Voting Machine Company, together with a full page advertisement for the machine, suggests a plan to teach people how to actually vote, quite likely in anticipation of the Voting Rights Act. Many, of course were being registered to vote for the first time. Along with the cancelled checks are bank statements from MIA offices around the country, bank books and copious records of expenditures. One bank book for the MIA looks like it might have been Martin Luther King Jr.'s.

The great beauty of this collection is the story it tells. How, from Rosa Parks' single act of civil disobedience, the Black communities of Montgomery and other cities and states seized the day, and began the process that culminated in the Civil Rights and Voting Rights Acts of 1964 and 1965. An appointment should be made to examine this lot.

The day after her arrest, Montgomery authorities were convinced that Parks had been a "plant", part of an NAACP plot to stir up trouble. But her act, according to Martin Luther King Jr. had been "an individual expression of a timeless longing for human dignity and freedom. . . . she was not 'planted' there by the NAACP or any other organization; she was planted there by her personal sense of dignity and self respect." (Stride Toward Freedom, page 44). Parks, a former secretary of a local NAACP, made the necessary phone call and E.D. Nixon, a local activist, came and signed her bond. In his first book, "Stride Toward Freedom," King describes the call he received from Nixon the day after the incident: "I listened deeply shocked, as he described the humiliating incident. 'We have taken this thing too long already,' Nixon concluded, his voice trembling. I feel the time has come to boycott the buses.'"

Within 72 hours the Montgomery Improvement Association was born, and a total boycott of Montgomery's buses began. A group of ministers and activists, led by King, Abernathy, Nixon, and Erna Dungee cobbled together a plan that would get Montgomery's 17,500 African American workers to and from their jobs during the boycott. At first, over two hundred Black cabbies offered to charge the same ten cents the bus fare would have been. But Montgomery's authorities, hoping to force blacks back to their buses, said that legally the cabbies had to charge each rider the minimum 45 cents per ride. Initially, individuals volunteered their cars, and pickup and drop-off zones were agreed upon. Surprisingly, many white women reluctant to lose their maids picked them up themselves. But a better plan had to be put in motion, and it was decided in April the MIA would acquire a fleet of station wagons and drivers. Within the four months of its creation, a great deal of money had been flowing in to the MIA from all over the country and from international sources as far off as Japan. The financial report shows that the MIA paid nearly $32,000 for a fleet of station wagons. Expenses for everything down to gas, oil and repairs for the vehicles is laid out. Additionally, there is a detailed "Report of the Committee on Station Wagons." That June financial report details everything regarding the purchase of the station wagons, and all of the other expenses of the MIA. There are careful records plus the checks that were written to all who were on salary, or for services rendered. A number of the earliest checks are co-signed by Martin Luther King Jr. (or in some cases his secretary Maude Ballou). The original constitution and by-laws for the MIA is present as well as the original ribbon copy of their first financial report, dated June 18, 1956 (in red ink at the top "Mrs Dungee"). There is also a mimeograph copy of their financial report, which is concurrent with the Supreme Court ruling in their favor, dated September 13, 1956. On the back of this report, Dungee has written "Since we got the Supreme Court's decision the crackers don't know what to do about putting the buses back on the streets. (!) The Law is that we ride + sit where we wish. The crackers are holding out now."

There are original citations for minor traffic infractions from the bus drivers, meant to harass the MIA, along with the records of payment. Together with all of the hand-written material, are several interesting piece of printed matter, such as King's "Our Struggle," printed and distributed by the MIA, and a scarce copy of the Third Annual Institute on Non-Violence and Social Change, an eight page pamphlet published by the MIA in December of 1958.

Sympathetic reaction, both nationally and internationally came surprisingly fast in the form of donations from widely diverse sources. The people of Boley Oklahoma, an affluent and entirely black community got together and opened an account for the MIA with a deposit for $5000!

The nearly 600 checks written by the MIA help to tell the story. A 1963 check written to the Shoup Voting Machine Company, together with a full page advertisement for the machine, suggests a plan to teach people how to actually vote, quite likely in anticipation of the Voting Rights Act. Many, of course were being registered to vote for the first time. Along with the cancelled checks are bank statements from MIA offices around the country, bank books and copious records of expenditures. One bank book for the MIA looks like it might have been Martin Luther King Jr.'s.

The great beauty of this collection is the story it tells. How, from Rosa Parks' single act of civil disobedience, the Black communities of Montgomery and other cities and states seized the day, and began the process that culminated in the Civil Rights and Voting Rights Acts of 1964 and 1965. An appointment should be made to examine this lot.

Exhibition Hours

Exhibition Hours

Aliquam vulputate ornare congue. Vestibulum maximus, libero in placerat faucibus, risus nisl molestie massa, ut maximus metus lectus vel lorem.