Sale 2444 - Lot 322

Price Realized: $ 2,800

Price Realized: $ 3,500

?Final Price Realized includes Buyer’s Premium added to Hammer Price

Estimate: $ 2,000 - $ 3,000

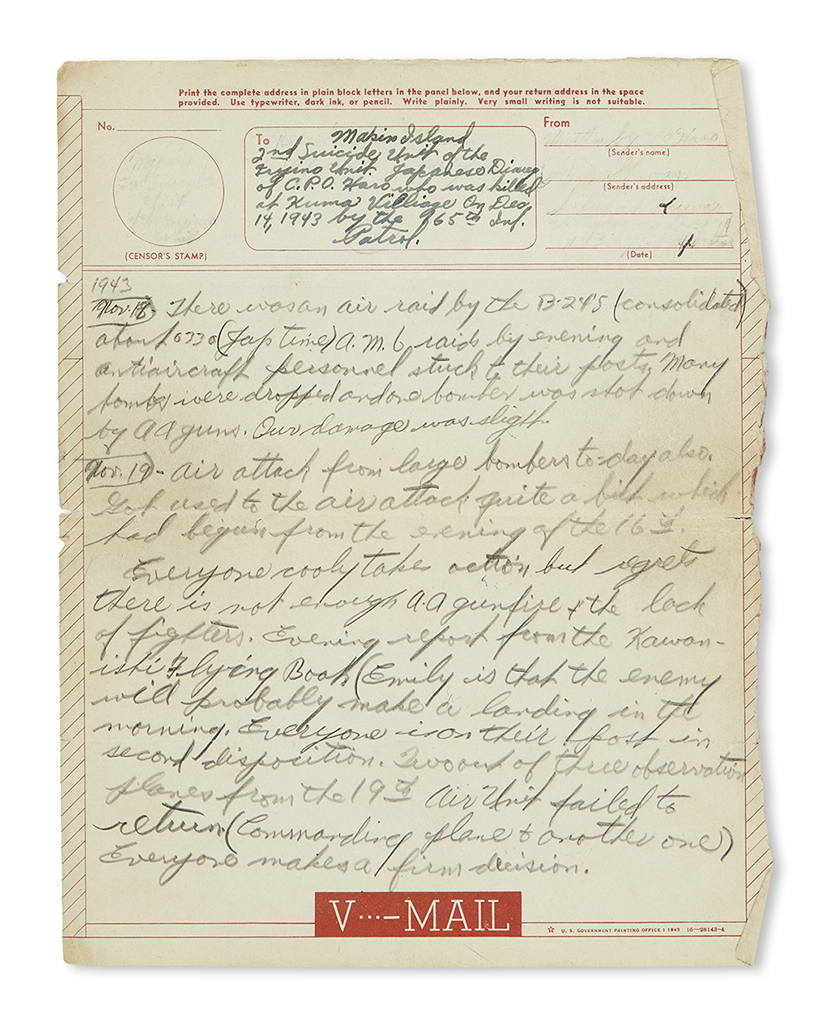

"I WAITED FOR TO THE END TO COME . . . THERE IS NO PLACE TO RUN." (WORLD WAR TWO.) Haro, Chief Petty Officer. Diary of a Japanese holdout during the Pacific campaign, translated after he was killed. 21 translated manuscript pages in English on printed V-Mail sheets, 11 x 8 1/2 inches; moderate edge wear. Makin Atoll, Gilbert Islands, 18 November to 13 December 1943

Additional Details

one of the most haunting diaries we have read. Japanese soldier Haro spent weeks evading American troops, slowly starving but determined to fight to the death.

The diary was written by a Japanese soldier on a small atoll in the Pacific, just north of the Equator. Before the war, this was known as Makin Atoll in the Gilbert Islands, a British protectorate. It was occupied by the Japanese in 1941, three days after Pearl Harbor. It is now known at Butaritari in the island nation of Kiribati. The atoll has only about 5 square miles of land, consisting mostly of two long narrow islands about a thousand feet across. A Japanese garrison of 806 men was tasked with defending the remote island to the death, with no expectation of reinforcement and no possibility of retreat. Surrender was not an option.

Chief Petty Officer Haro's diary (as translated by an American G.I.) tells the story of the Battle of Makin and his continued resistance for an amazing 20 days after the Americans declared victory. It begins on 18 November with American air raids, followed by the landing of 6,000 Allied troops on 20 November. The next day Haro wrote "Coconut trees are blown up & craters are all around. Can't believe that this could be Makin Island. Seems strange everybody including commander is still alive." By the end of the day, the Japanese commander and many of the troops had died: "The remaining men in the east position are determined to die and with only rifles they await the enemy. . . . We know that we are going to die, so we have no fear of anything or anybody, & everyone is high-spirited." The American command declared victory on 23 November, and commenced mop-up operations. That day, Haro's surviving comrades got "into high spirits by drinking beer which was in the church" and sent several wounded men on a suicide mission. Haro retreated with a group of 16 men facing American tank and machine gun fire, and was "clipped in the mouth by a bullet." An air raid hit their shelter on 25 November, reducing the survivors to four men: "Though we are alive, figure that we only will live about 2 or 3 days. All of us put the muzzle of the gun to our throats several times to commit suicide, but . . . why not stick it out to the finish?" The four crossed an inlet to the northern island of Kuma on 28 November and found it also crawling with American tanks. They found friendly natives, purloined some American supplies, and were able to relax enough to cook some rice on 30 November ("we will never forget the taste of rice eternally") and get a good night's sleep: "We think it is because we had plenty to eat & smoked the enemy's best tobacco." They learned that Americans were telling natives "that if any Japanese soldiers came to the village, to tell them to give up. Don't make me laugh. Buried enemy hand grenades in the road to destroy enemy tanks" (2 December). Haro's little group of four survivors was broken up on 4 December. One man ran off and another was mortally wounded: "Engineer Nakada was not quite dead and was suffering, so we finished him off with one round. This is also showing our love for our comrade. We know that he will not be taken prisoner." Haro and his comrade Atobe, down to 30 rounds of ammunition, made for the village of Shima. Miraculously, after not seeing another Japanese for many days, they found 8 other holdouts who had been building a raft to escape across the open ocean to Japan. During another inlet crossing on 7 December, Haro hit a low point when he lost his weapons: "Finally the end has come & it is impossible to commit suicide. Everything was lost in the sea. Holding a rock in each hand, I waited for the end to come for about two hours. There is no place to run away & figuring if I threw the rock they would shoot me." On 13 December, he wrote: "Plan to go to Kuma in the night." These are the final words in the diary. Haro was killed in Kuma the next day by the 165th Infantry Patrol.

The original diary was found on Haro's body, and given to Private Joseph P. Gambino (1918-1987) of the 111th Infantry for translation. He wrote out his translation on 21 sheets of V-Mail paper, had the translation typed, and then handed in the original diary and his typescript to military intelligence. He kept his manuscript translation as a memento, which is what is offered here for sale. In 1949, he gave it to his niece Frances Caliendo (1932-2009) of Elizabeth, NJ. Included with Gambino's original manuscript translation of the Haro diary are a later typescript and 3 comparatively mundane war-date letters from Gambino to Caliendo, 1943-44.

We do not know the fate of Haro's original diary, but the official military typescript is preserved in the National Archives as part of the Records of the War Department General and Special Staffs (RG 165). It was the basis of an article by Jennifer N. Johnson, "We're Still Alive Today: A Captured Japanese Diary from the Pacific Theater," in Prologue Magazine 45:2 (Summer 2013). Apparently, the National Archives typescript does not reveal the name of the diarist, or when and where he was killed. With the appearance of this manuscript translation, these mysteries are now solved. Knowing the resolution of the story, this diary could serve as the basis of a powerful book or film.

The diary was written by a Japanese soldier on a small atoll in the Pacific, just north of the Equator. Before the war, this was known as Makin Atoll in the Gilbert Islands, a British protectorate. It was occupied by the Japanese in 1941, three days after Pearl Harbor. It is now known at Butaritari in the island nation of Kiribati. The atoll has only about 5 square miles of land, consisting mostly of two long narrow islands about a thousand feet across. A Japanese garrison of 806 men was tasked with defending the remote island to the death, with no expectation of reinforcement and no possibility of retreat. Surrender was not an option.

Chief Petty Officer Haro's diary (as translated by an American G.I.) tells the story of the Battle of Makin and his continued resistance for an amazing 20 days after the Americans declared victory. It begins on 18 November with American air raids, followed by the landing of 6,000 Allied troops on 20 November. The next day Haro wrote "Coconut trees are blown up & craters are all around. Can't believe that this could be Makin Island. Seems strange everybody including commander is still alive." By the end of the day, the Japanese commander and many of the troops had died: "The remaining men in the east position are determined to die and with only rifles they await the enemy. . . . We know that we are going to die, so we have no fear of anything or anybody, & everyone is high-spirited." The American command declared victory on 23 November, and commenced mop-up operations. That day, Haro's surviving comrades got "into high spirits by drinking beer which was in the church" and sent several wounded men on a suicide mission. Haro retreated with a group of 16 men facing American tank and machine gun fire, and was "clipped in the mouth by a bullet." An air raid hit their shelter on 25 November, reducing the survivors to four men: "Though we are alive, figure that we only will live about 2 or 3 days. All of us put the muzzle of the gun to our throats several times to commit suicide, but . . . why not stick it out to the finish?" The four crossed an inlet to the northern island of Kuma on 28 November and found it also crawling with American tanks. They found friendly natives, purloined some American supplies, and were able to relax enough to cook some rice on 30 November ("we will never forget the taste of rice eternally") and get a good night's sleep: "We think it is because we had plenty to eat & smoked the enemy's best tobacco." They learned that Americans were telling natives "that if any Japanese soldiers came to the village, to tell them to give up. Don't make me laugh. Buried enemy hand grenades in the road to destroy enemy tanks" (2 December). Haro's little group of four survivors was broken up on 4 December. One man ran off and another was mortally wounded: "Engineer Nakada was not quite dead and was suffering, so we finished him off with one round. This is also showing our love for our comrade. We know that he will not be taken prisoner." Haro and his comrade Atobe, down to 30 rounds of ammunition, made for the village of Shima. Miraculously, after not seeing another Japanese for many days, they found 8 other holdouts who had been building a raft to escape across the open ocean to Japan. During another inlet crossing on 7 December, Haro hit a low point when he lost his weapons: "Finally the end has come & it is impossible to commit suicide. Everything was lost in the sea. Holding a rock in each hand, I waited for the end to come for about two hours. There is no place to run away & figuring if I threw the rock they would shoot me." On 13 December, he wrote: "Plan to go to Kuma in the night." These are the final words in the diary. Haro was killed in Kuma the next day by the 165th Infantry Patrol.

The original diary was found on Haro's body, and given to Private Joseph P. Gambino (1918-1987) of the 111th Infantry for translation. He wrote out his translation on 21 sheets of V-Mail paper, had the translation typed, and then handed in the original diary and his typescript to military intelligence. He kept his manuscript translation as a memento, which is what is offered here for sale. In 1949, he gave it to his niece Frances Caliendo (1932-2009) of Elizabeth, NJ. Included with Gambino's original manuscript translation of the Haro diary are a later typescript and 3 comparatively mundane war-date letters from Gambino to Caliendo, 1943-44.

We do not know the fate of Haro's original diary, but the official military typescript is preserved in the National Archives as part of the Records of the War Department General and Special Staffs (RG 165). It was the basis of an article by Jennifer N. Johnson, "We're Still Alive Today: A Captured Japanese Diary from the Pacific Theater," in Prologue Magazine 45:2 (Summer 2013). Apparently, the National Archives typescript does not reveal the name of the diarist, or when and where he was killed. With the appearance of this manuscript translation, these mysteries are now solved. Knowing the resolution of the story, this diary could serve as the basis of a powerful book or film.

Exhibition Hours

Exhibition Hours

Aliquam vulputate ornare congue. Vestibulum maximus, libero in placerat faucibus, risus nisl molestie massa, ut maximus metus lectus vel lorem.