Sale 2633 - Lot 180

Price Realized: $ 15,000

Price Realized: $ 18,750

?Final Price Realized includes Buyer’s Premium added to Hammer Price

Estimate: $ 6,000 - $ 9,000

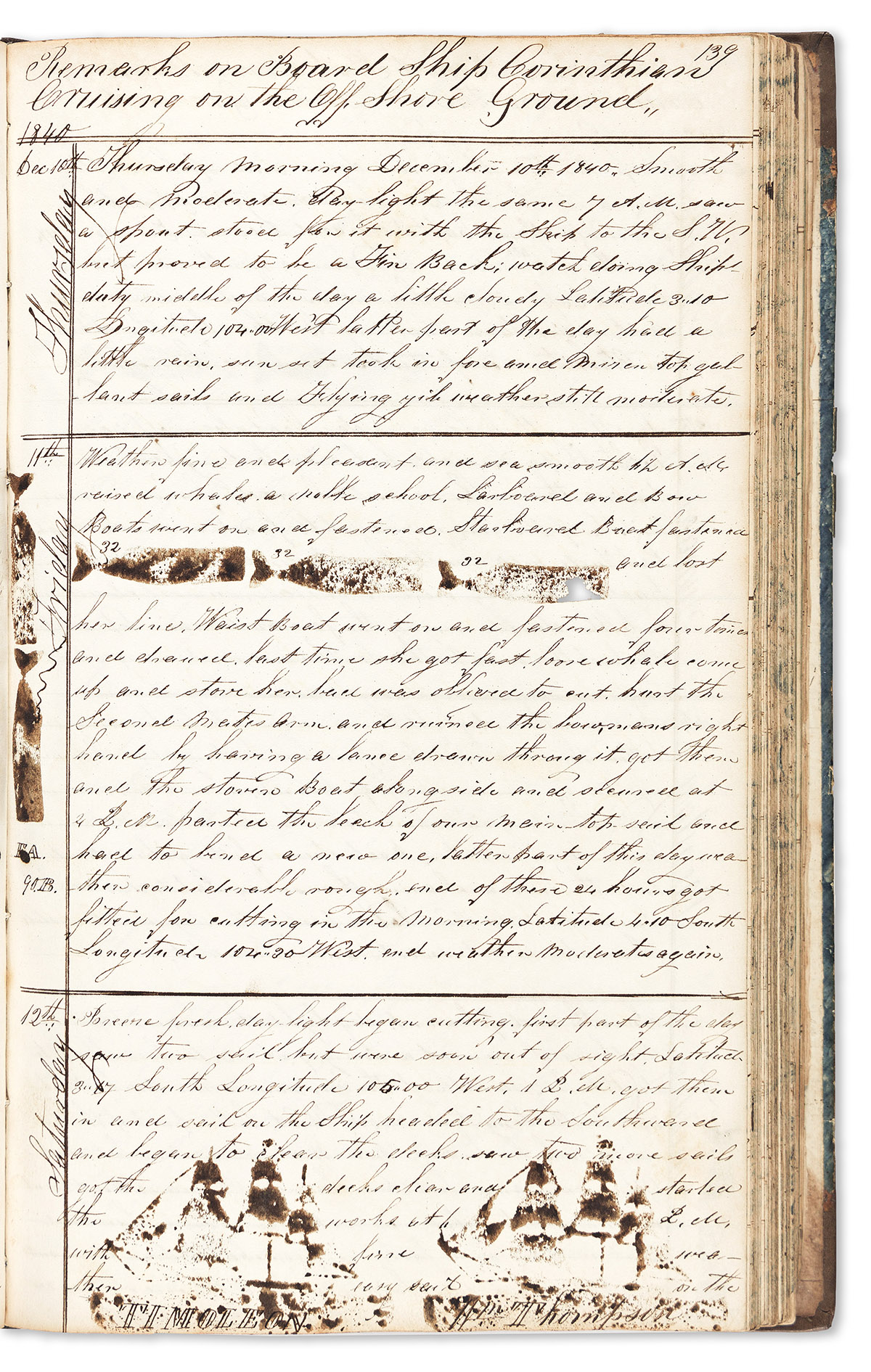

(WHALING.) Francis Harrisson. Journal of a third mate on a four-year whaling expedition to the South Pacific. [6], 348 manuscript pages. Folio, contemporary 1/2 calf over marbled boards, moderate wear, rebacked; generally minor wear to contents, moderate edge wear to a few leaves near end, tape repair to one leaf. Various places, 11 August 1839 to 7 August 1843

Additional Details

The keeper of this personal diary / journal was Francis Harrisson (1809-1883) of New Bedford, MA. He was by this point a veteran mariner, having already made several voyages around Cape Horn. In 1839 he shipped out as third mate on the Corinthian. The ship stopped, among other places, the Azores; Juan Fernandez Islands off Chile; Paita and Callao, Peru; Talcahuano, Chile; and Pernambuco, Brazil. They also stopped briefly in the Galapagos Islands, 5 years after Darwin's visit (3 May 1840).

The main attraction in any whaling log is of course the dramatic stories of the hunt, and this journal does not disappoint. On 10 June 1840: "Raised a school of large whales, lowered three boats. Larboard boat went on and fastened, and got cut in two pieces, 8 men on each half. Waist boat went to pick up the line to the piece of boat that the whale was fast to, and getting the men off got stove slightly. Bow boat picked up the other three and fastened to the whale and saved him. Waist boat cut and went on board. The other whales brought to but we had no boat to get them, as the starboard boat had gone to pick up what she could out of the stoven boat, and then she got stoven badly by the wreck, but saved one end of the boat oars and a few other things, the craft and line lost, but there was no one hurt in the scrape, but badly frightened." On 11 December 1840: "Raised whales, a noble school. Larboard and bow boats went on and fastened. Starboard boat fastened and lost her line. Waist boat went on and fastened our times and drawed, last time she got fast. Loose whale come up and stove her bad, was obliged to cut. Hurt the second mate's arm, and ruined the bowman's right hand by having a lance drawn through it. Got them and the stoven boat alongside and cleared." Finally, on 5 July 1841 a man is mauled by a shark while bring a whale aboard: "Raised a school of whales. Lowered and got two, one by the larboard and one by the waist boats. Larboard boat got stove bad. Bows boat had to go and pick the crew up, and then went and caught the line that was fast to the whale and so saved him. Got them alongside and secured at 10 a.m., also the stoven boat. . . . We concluded to begin and cut, and the man that we had overboard to hook on got bit by a shark pretty bad."

This voyage largely overlaps with the period that Herman Melville was in the South Pacific as a whaler (1841-1844), although they apparently did not cross paths. They did cross paths with the famed and venerable warship, the USS Constitution, which was in port at Paita, Peru when they arrived. The Corinthian's crew attended a theatrical amusement aboard the Constitution "which passed off quite pleasant" (10 October 1840), and then two days later had the Constitution intervene in the case of some crewmen who refused to leave port: "Com'd Clarkson and the American consul came off and gave ordered to have them seized up and flogged if they did not do their duty now and hereafter, of which they went to work." Harrisson had a brother who was also at sea in the South Pacific during his period, writing "Understand that my brother left the ship in Otaheite" (12 December 1840), and finally catching up with him almost two years later: "Your author went up to the city of Lima and found his brother" (10 August 1842).

The Corinthian's master, Captain Joseph Paddock was apparently a most unpleasant man, spiteful and sadistic. He spent the last two years of this voyage trying to provoke Harrisson into a confrontation, without success. On 1 June 1841, the Corinthian's second mate left the ship, and Captain Paddock hired another man rather than promote Harrisson: "The old man and myself had a few words about it. Could have given me the berth, but keeps me down, as he knows it will hurt me. I asked him for my discharge, but he refused and said that if I left the ship, I should have to run away. . . . I then asked him to let me go on shore for a few minutes, but he would not, and said that I had insulted him grossly. . . . Hope and pray that this voyage may be short." The would remain together on the ship for two more years. Later that month, "Old man called me up and said I had not done anything this three months, entitled me a passenger and mutinous before the majority of the ship's company" (26 June 1841).

Other crewmen fared less well, with Harrisson often detailed to do the flogging: "Seized the steward up in the main rigging and gave him twenty eight lashes by Capt. Paddack for insolence and repeated disobedience of orders. Called all hands aft to see it performed" (13 March 1841). "Old man made the cook eat some bread that he had not baked enough, as hot as he could get it down. Strange works, voyage is d----d" (9 July 1841). Paddock became enraged at another man and "struck him two severe blows over the shoulder with the end of his fore brace, for not getting his wood up before breakfast" (18 September 1841). On 17 May 1843: "Old man just been a flogging the man that we shipped in Talcahuano with an unlawful rope, because he did not do a trifling job to suit him." As the ship neared its fourth year at sea, Paddock seemed to be keeping the men from home out of spite: "The old man bought meat and flour in Talcahuano and we have got to stop and eat that up, as it would not do to carry it home, so we shall dwindle away three months more, as we have the last nine, and get nothing. This ship could have been at home by last New Year's Day with as much oil as she has now. Here we are with hardly a man on board of the ship good for anything, and what there is they are discouraged, and the old man prolonging the time out of mere spite" (29 May 1843). With the end in sight, Harrisson kept biting his tongue: "He wants to pick a quarrel with me, but he shall not if I can any way avoid it. He has tried it this last 24 months" (18 June 1843).

Harrisson was a mild-mannered man, missing church and the comforts of home. In the wild port of Tahiti: "Otaheite has a different appearance than what your author saw it three years ago. . . . Hope that we may get away from here pretty soon, as there is nothing here that appertains towards decency" (19 and 26 May 1841). On 31 August 1842 he wrote: "I hope by this time another year to be a married man, although I have no one in view to my knowledge, but I am in hopes, as I have made up my mind if I live to have a wife, if there is one to be found that will suit your author." Although he remained at sea almost a year more, he almost beat his prediction. His marriage to one Nancy Barker Rich was recorded in New Bedford on 13 September 1843, just 37 days after returning to port. Harrisson gave up whaling and was a house painter by the time of the 1850 census.

Like many of the best whaling journals, this one is richly illustrated with inked stamps to denote every whale hunted, and every ship encountered--more than 300 stamps in total. A pencil drawing of a young woman is laid down on the front pastedown (perhaps Harrisson's imaginary bride-to-be), and an engraving of author James Smith is laid down on the rear pastedown. In addition to journal entries, the volume also includes carefully annotated lists of vessels seen; ports visited; whales lost; officers and crew; and a list of whales raised by each man (with a profusion of whale stamps to make the point).

An unusually insightful and lively whaling journal. Additional abstracts available upon request.

The main attraction in any whaling log is of course the dramatic stories of the hunt, and this journal does not disappoint. On 10 June 1840: "Raised a school of large whales, lowered three boats. Larboard boat went on and fastened, and got cut in two pieces, 8 men on each half. Waist boat went to pick up the line to the piece of boat that the whale was fast to, and getting the men off got stove slightly. Bow boat picked up the other three and fastened to the whale and saved him. Waist boat cut and went on board. The other whales brought to but we had no boat to get them, as the starboard boat had gone to pick up what she could out of the stoven boat, and then she got stoven badly by the wreck, but saved one end of the boat oars and a few other things, the craft and line lost, but there was no one hurt in the scrape, but badly frightened." On 11 December 1840: "Raised whales, a noble school. Larboard and bow boats went on and fastened. Starboard boat fastened and lost her line. Waist boat went on and fastened our times and drawed, last time she got fast. Loose whale come up and stove her bad, was obliged to cut. Hurt the second mate's arm, and ruined the bowman's right hand by having a lance drawn through it. Got them and the stoven boat alongside and cleared." Finally, on 5 July 1841 a man is mauled by a shark while bring a whale aboard: "Raised a school of whales. Lowered and got two, one by the larboard and one by the waist boats. Larboard boat got stove bad. Bows boat had to go and pick the crew up, and then went and caught the line that was fast to the whale and so saved him. Got them alongside and secured at 10 a.m., also the stoven boat. . . . We concluded to begin and cut, and the man that we had overboard to hook on got bit by a shark pretty bad."

This voyage largely overlaps with the period that Herman Melville was in the South Pacific as a whaler (1841-1844), although they apparently did not cross paths. They did cross paths with the famed and venerable warship, the USS Constitution, which was in port at Paita, Peru when they arrived. The Corinthian's crew attended a theatrical amusement aboard the Constitution "which passed off quite pleasant" (10 October 1840), and then two days later had the Constitution intervene in the case of some crewmen who refused to leave port: "Com'd Clarkson and the American consul came off and gave ordered to have them seized up and flogged if they did not do their duty now and hereafter, of which they went to work." Harrisson had a brother who was also at sea in the South Pacific during his period, writing "Understand that my brother left the ship in Otaheite" (12 December 1840), and finally catching up with him almost two years later: "Your author went up to the city of Lima and found his brother" (10 August 1842).

The Corinthian's master, Captain Joseph Paddock was apparently a most unpleasant man, spiteful and sadistic. He spent the last two years of this voyage trying to provoke Harrisson into a confrontation, without success. On 1 June 1841, the Corinthian's second mate left the ship, and Captain Paddock hired another man rather than promote Harrisson: "The old man and myself had a few words about it. Could have given me the berth, but keeps me down, as he knows it will hurt me. I asked him for my discharge, but he refused and said that if I left the ship, I should have to run away. . . . I then asked him to let me go on shore for a few minutes, but he would not, and said that I had insulted him grossly. . . . Hope and pray that this voyage may be short." The would remain together on the ship for two more years. Later that month, "Old man called me up and said I had not done anything this three months, entitled me a passenger and mutinous before the majority of the ship's company" (26 June 1841).

Other crewmen fared less well, with Harrisson often detailed to do the flogging: "Seized the steward up in the main rigging and gave him twenty eight lashes by Capt. Paddack for insolence and repeated disobedience of orders. Called all hands aft to see it performed" (13 March 1841). "Old man made the cook eat some bread that he had not baked enough, as hot as he could get it down. Strange works, voyage is d----d" (9 July 1841). Paddock became enraged at another man and "struck him two severe blows over the shoulder with the end of his fore brace, for not getting his wood up before breakfast" (18 September 1841). On 17 May 1843: "Old man just been a flogging the man that we shipped in Talcahuano with an unlawful rope, because he did not do a trifling job to suit him." As the ship neared its fourth year at sea, Paddock seemed to be keeping the men from home out of spite: "The old man bought meat and flour in Talcahuano and we have got to stop and eat that up, as it would not do to carry it home, so we shall dwindle away three months more, as we have the last nine, and get nothing. This ship could have been at home by last New Year's Day with as much oil as she has now. Here we are with hardly a man on board of the ship good for anything, and what there is they are discouraged, and the old man prolonging the time out of mere spite" (29 May 1843). With the end in sight, Harrisson kept biting his tongue: "He wants to pick a quarrel with me, but he shall not if I can any way avoid it. He has tried it this last 24 months" (18 June 1843).

Harrisson was a mild-mannered man, missing church and the comforts of home. In the wild port of Tahiti: "Otaheite has a different appearance than what your author saw it three years ago. . . . Hope that we may get away from here pretty soon, as there is nothing here that appertains towards decency" (19 and 26 May 1841). On 31 August 1842 he wrote: "I hope by this time another year to be a married man, although I have no one in view to my knowledge, but I am in hopes, as I have made up my mind if I live to have a wife, if there is one to be found that will suit your author." Although he remained at sea almost a year more, he almost beat his prediction. His marriage to one Nancy Barker Rich was recorded in New Bedford on 13 September 1843, just 37 days after returning to port. Harrisson gave up whaling and was a house painter by the time of the 1850 census.

Like many of the best whaling journals, this one is richly illustrated with inked stamps to denote every whale hunted, and every ship encountered--more than 300 stamps in total. A pencil drawing of a young woman is laid down on the front pastedown (perhaps Harrisson's imaginary bride-to-be), and an engraving of author James Smith is laid down on the rear pastedown. In addition to journal entries, the volume also includes carefully annotated lists of vessels seen; ports visited; whales lost; officers and crew; and a list of whales raised by each man (with a profusion of whale stamps to make the point).

An unusually insightful and lively whaling journal. Additional abstracts available upon request.

Exhibition Hours

Exhibition Hours

Aliquam vulputate ornare congue. Vestibulum maximus, libero in placerat faucibus, risus nisl molestie massa, ut maximus metus lectus vel lorem.